“Mahalaga kasi sa akin yung relationship, kaysa sa kahit ano,” he reasons. (“It’s because relationships are important to me above anything else.”) This is why he vows to continue the project until he receives the last letter. Photography by Jake Verzosa

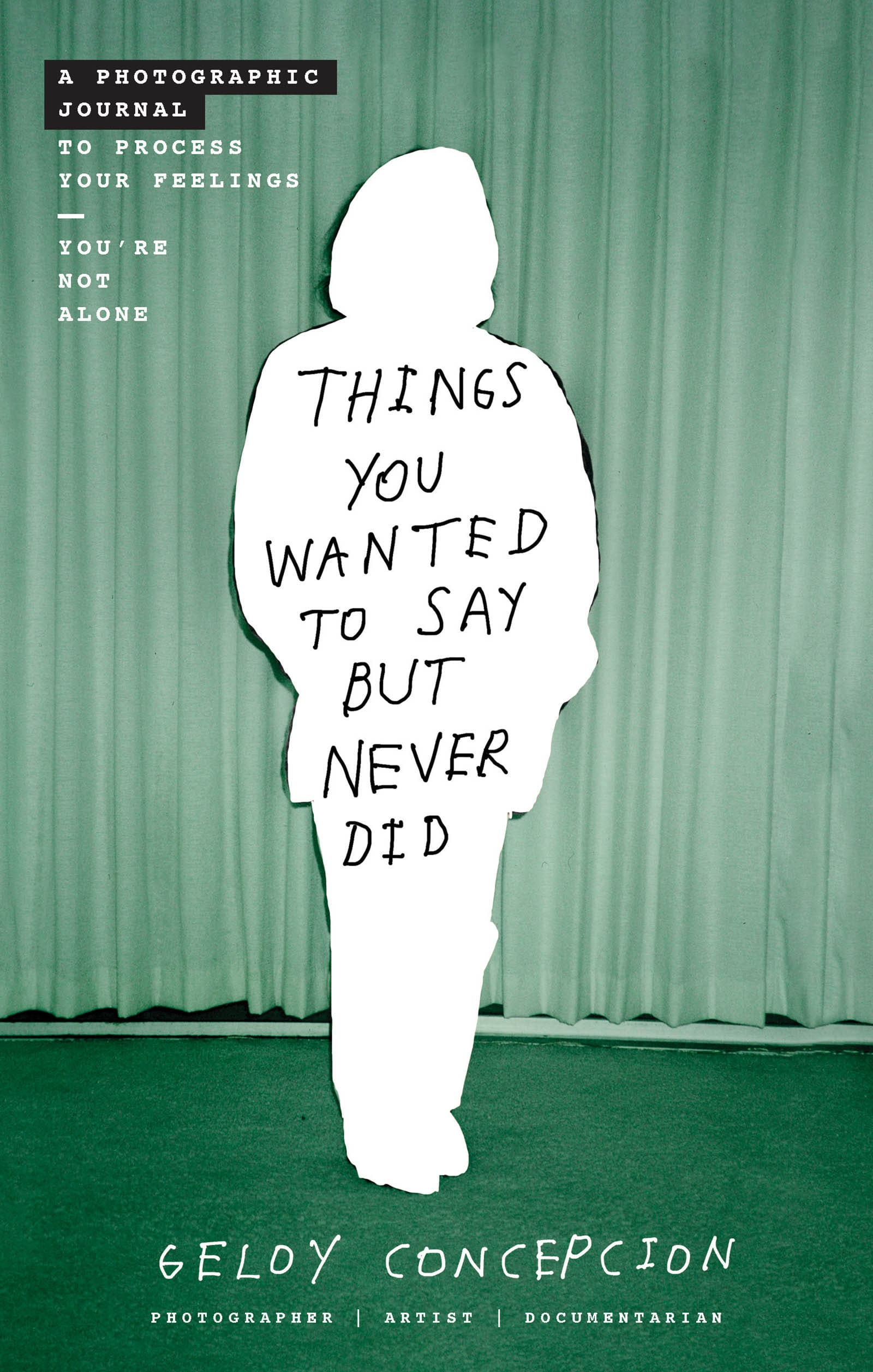

Across the globe, people have been telling Geloy Concepcion their secrets. We sit down with him to talk about his book, an extension of the project that will last as long as people trust him with their thoughts.

In Manila, everyone talks to you like they’ve known you for ages. Weaving through the busy alleys of the Dangwa flower market, it’s apparent. Linger at a stall a second too long and its owner might convince you to bring a small bouquet home (or maybe more if they’re really good).

That is how Geloy Concepcion finds himself looking at tulips inside a florist’s cold room tucked in one of the flower shops in the area. After talking to a florist along Dimasalang street, their conversation somehow led them to a detour to see the flowers hidden in a huge cooler. Walking out with nothing in hand, Geloy laughs. “At least nakita na natin kung ano nasa loob ng mga ito, diba!” (“At least we got to see what’s inside these things, right?”) He’s used to situations like this.

Growing up in Manila, surrounded by carefree, blunt, but nonetheless hospitable talkers of all kinds molded Geloy’s work as a portrait photographer and an artist for many years. It’s why his persona online always feels familiar even to strangers. It’s also why so many people from around the world trust him with their closely kept secrets.

After migrating to the United States in 2017, he began a project to dispose of old film photos that had been piling up from his work as a photographer. Feeling lonely and struggling with his family to adjust in a new country so far away from home, he was thinking of ways to reach out to the world from his small room. On his social media account he posted one question for his friends to see: What are things you wanted to say but never did?

“Sana magaling ako mag English para hindi isipin ng mga Amerikano na tanga ako,” (I wish I was good at speaking in English so the Americans don’t think I’m dumb.”) his first post read, scribbled down on old film. And perhaps it’s that candid admission that invites others to let down their guard, too. As a portrait photographer himself, he knows that his vulnerability and how he connects with others is essential in his art.

“Sa totoo lang, pinagkakatiwalaan ka ng tao ng mabilis,” he says. “Mas at ease ang mga tao kapag nakakausap mo sila. Kasi kailangan mo din yun eh. Kung may sasabihan ka ng mga sikreto, dapat kilala mo sila.” (“In truth, you have to make people trust you quickly. And they are more at ease with you if you talk to them. You need that connection. If anyone’s going to tell you their secrets, they have to get to know you first.”) As a self-described homegrown Manila boy, he has this innate skill to talk to — and reveal himself — to everyone like an old friend. And the effect is evident even in his portraiture: it’s in his subject’s eyes, the slack of the shoulders, and the lips – upturned while laughing, shaped like an “o” in the middle of telling him a fascinating story, or relaxed in a barely-there smile.

After his first post, he expected about forty submissions, then he’d be done with the project. But more responses kept piling up. At one point, he turned to his wife and admitted that maybe, he’s onto something big.

Now, his virtual mailbox has amassed over 200,000 letters already. It’s something akin to a virtual confessional. On one side, a stranger from the Philippines or the United States. (But these days, he tells me, most of his submissions come from Serbia, Kazakhstan, Poland, Pakistan, and countries far away). And on the other, a tattooed man from Manila who used to draw graffiti around the city and likes taking photos. While telling his story, he doesn’t claim to be anything more than an artist who wants to listen.

He reads each of those strangers’ confessions and writes it onto a photo that is then posted among other confessions on his Instagram page. They contain stories of hurt, regret, and trauma. But he sifts through the submissions to find bright spots too – sometimes people send over stories of hope. Wishes for the future are tossed in also, waiting to be spoken, hopefully, into existence. Each post has become a pocket community of readers. People start conversations in the photos’ comment section, who then find others who are going through the same experiences as they do.

At this point the project has become an archive of the mental state of one sizable corner of the internet. As heavy as some of the confessions may seem, one can imagine that finding a photo that speaks to your own experiences can feel like airing out a healing wound. “Mahalaga kasi sa akin yung relationship, kaysa sa kahit ano,” he reasons. (“It’s because relationships are important to me above anything else.”) This is why he vows to continue the project until he receives the last letter.

His book, a guided journal titled after the question he’s known for asking, is an extension of his online project. He wants his questions to reach people outside of social media in hopes that the reflection could help others. Reading all these strangers’ thoughts has made him kinder and more considerate of strangers’ hidden struggles. Maybe, the same could happen to others if he reaches a wider range of people.

“Para ito sa mga taong walang internet, mga nasa kulungan, sa home for the aged. Kasi kung sa Instagram lang ang project na ito, limited din siya in a way.” (“This book is for those who don’t have internet access, those in prisons, in homes for the aged because if I just keep this in Instagram, its reach is limited too, in a way.”)

- Erwan Heussaff Wins A James Beard Award And Puts The Global Spotlight On Filipino Food

- 10 Books On The Filipino Experience

- Literary Treasure: Nolledo’s “But for the Lovers” Is Now Back In The Spotlight

- LIFESTYLE

“The Sway and Emotions of Childhood Tend to Keep Some Power”: Laurel Fantauzzo Debuts Her YA Novel 10 Years in the Making