Photo by Bianca Catbagan

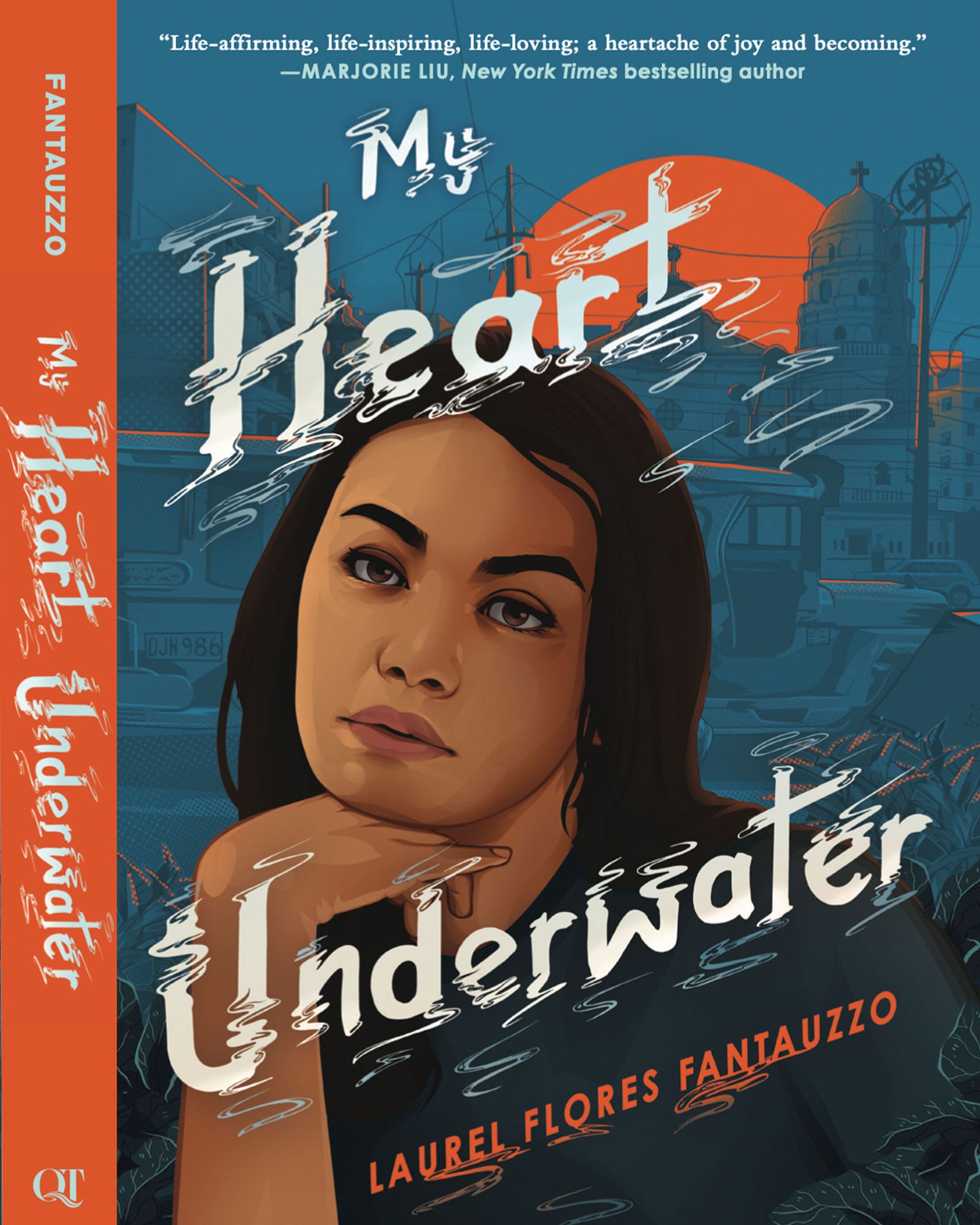

It took Laurel Flores Fantauzzo ten years to finish her debut young adult novel My Heart Underwater. Based on a short story she wrote in 2009, the book was completed and sold in 2019.

In My Heart Underwater, Corazon “Cory” Tagubio finds herself packing her bags for the Philippines after a series of unfortunate events forces her mom to send her to live and stay with a half-brother whom she has never met. As Fantauzzo explains, the main character goes from lonely, closeted, and panicky teenager in Southern California to accompanied, insecure, and (still) panicky in Teachers Village, with an older brother that she grew up with via Skype.

The relationship between identity and place and how it informs upbringing comes up frequently. For Fantauzzo, her latest book, released in paperback this November 21, is less an exercise in catharsis, and more a way to open up the conversation to readers who may see themselves in Cory’s story.

“In my perception, individual Manila households have their own (hopefully) patient, nurturing routines and rituals, while the public worlds of Metro Manila both rush and delay the people in them,” she says. “I also wasn’t sure how to depict, for a long time, Cory learning, and resisting, the multilayered classism of Metro Manila. I came to learn that she has always been aware of class differences in her own family, and between her own parents, but that those differences confront her on a megalopolis scale for the first time, when she visits Manila.”

The following interview was conducted over Zoom and has been edited for clarity.

VOGUE: What was the impetus for this kind of story that you wanted to tell?

LAUREL FANTAUZZO: I think the sway and emotions of childhood tend to keep some power over artists. And I guess it’s my attempt to respect the strength of my own anxiety from my teenage era, while also synthesizing that with my Fil-Am anxiety within a Philippine context, and then also feeling like a misfit in various kinds of families and relationships.

Could you describe that Fil-Am anxiety you were talking about?

I’m not speaking of an anxiety about feeling trapped within borders, and social and political conditions, which itself is an incredibly structurally imposed anxiety. For me, I think it’s very emotional, and also part of the experience of growing up in an America that, for most of its audiences, and most of its communities, has White America as its priority.

I think young Filipino Americans grow up being a little bit psychologically tortured by racism and invisibility, and those kinds of psychological attacks, while also being told that it doesn’t matter, from our parents who survived material conditions that in many cases were, according to them, much worse. And then if you’re queer and closeted with no social support, or very dysfunctionally erased, and lack of advice around relationships, you get into all sorts of specific kinds of trouble. So I think I wanted to speak to that trouble.

There’s been a lot of discourse on creating work that makes the invisible visible especially for minorities and people of color. Can you talk about your process of trying to articulate this?

One is the validity of the existence of an experience which is a value in and of itself. And then there is a market. Sometimes never the twain shall meet. [Laughs]

I can imagine how challenging that must be. You’re hoping for something that in some ways is already true. That you know that there is an audience for your work and yet you still have to prove that they exist in some way.

Yeah, I think it’s a challenge, because it’s a fact that in American publishing, the majority of workers in American publishing are White American women and that’s just how it is right now. That’s the demographic. Audience is another thing to consider. If I’m only considering an audience that is unfamiliar with the Philippines, then of course parts of my writing are going to change. And if an editor has only that audience in mind, they’re going to ask me to spend extra time explaining or translating or using fewer, quote unquote, foreign words, to reach that audience. And so what I was looking for and what I was lucky to find was an editor who was willing to have an expansive sense of audience, which is that it’s not only those who have never heard of the Philippines or would need many things translated to them. But it’s also members of the diasporas. It’s also an enormous Filipino-American diaspora. It’s Filipinos in the Philippines and abroad. It’s queer audiences, it’s anxious young people. You can make an argument that anything is, quote unquote, niche if you don’t have an expansive sense of who might need or be interested in that niche. I think the word niche might betray a lack of curiosity and imagination.

Since your book centers on a Fil-Am protagonist, what are your thoughts on the differences between a Filipino audience and a Fil-Am or Filipinx audience?

Are we still there? [Laughs] I think a lot of it is distributions of energy, and what different audiences might demand of different authors. And it also speaks to a hunger to be accounted for when you are not accounted for. If you’re not spoken to or about, if you feel that someone has attempted it, and is doing it wrong, you feel that a wrong has been compounded. And so instead of perhaps extending a generosity to a creator, you might say, you now have compounded my sense of betrayal.

So, I think a lot of sides of that conversation come from a real sense of self protection and also, I guess I can use the word gatekeeping. And it also makes me think why is there a gate in the first place? What has been protected? What are you trying to keep out? And I think there’s a sense of woundedness and imposition that you want to resist. Is that where the energy of our resistance goes? Is it towards a member of our community that is using, quote unquote, the wrong word? Or can it go towards external conditions that have come to crash our gates? I know where I would like my energy to go.

But if I could change one thing, I have seen the word “mainland” being used to refer to the Philippines and I want to yell and just pound on every table and go, “It is not a mainland! It is an archipelago. Stop calling it the mainland!” It’s a terrible word. Anyway, please put that in.

“I don’t know that it’s cathartic for me to write, in the sense of writing for the sake of writing, but I think it’s very fulfilling to be in relationship with readers and talk about their own relationship to something I made.”

Since we’re on the subject, how do you articulate that relationship between identity and place?

I can only do it through character. And I think part of the process of respecting the character is knowing when the character is not me. And also imbuing that character with an emotional understanding that I might or might not have. When she is forced under very traumatizing and shocking circumstances to live with her half brother in Teachers Village, she’s disoriented by the Philippines. She doesn’t want to be there. She immediately notices the abusive, often class-based and family-based interactions that are occurring and she rebels against them. And then, when she gets to her brother’s apartment that her father has been supporting for years and years, there’s an instant sense of home and familiarity. And so I think there are many ways in which parts of her upbringing and self-knowledge are reflected or rejected by her physical environments.

What would you say is the thing that most people take for granted when it comes to identity and that sense of belonging?

It’s hard because, again, the question of the audience comes to mind when I hear the phrase “most people.” I can only speak for myself but I am utterly baffled when someone has been able to stay in one place, or have one identifiable family home that they can return to no matter what. Because to me, and in my own background, that always feels very borrowed to me. That sense of having a home base does not really exist for me. I’ve written about this in my previous essays, that I would always be so amazed when my Filipino friends who are middle class or upper middle class, like every Sunday, have the family repast to go to. This would just never be possible for me. I wouldn’t accuse them of taking it for granted but I find that so amazing to me.

I don’t like it when I hear that feeling secure in yourself is a choice, or feeling you are content in your home base is something that’s entirely self-invented. Because that just once again erases so many historical and personal factors that have placed so much pressure on a person to survive. And often, that has nothing to do with a personal choice.

When you were saying how you didn’t feel like home was permanent even from a young age, how did that inform your view of the world?

You know, and this is happening even now in my life, which is that there are simple physical details such as, I can’t use nails in the walls, I can’t buy frames that are too heavy. Because within the next 18 to 24 months, I’m going to the next place. And so there are those small logistical physical details. And then, there’s also sort of a constant sense of, at the worst of it, uncertainty. Perhaps it could look like noncommittal dilettantism. At best, it can be an openness to what might come next, and a life that may not look like other lives.

And so, I think that’s how it informed me. Not having a singular physical community or family-based sense of home can be an openness to what might come next and an ability to form friendships and alliances with individuals all over the world.

Since the name does evoke that imagery of a heart, what for you is at the heart of the relationship between identity and place?

I think uncertainty is at the heart of everything. And then how do you interact with that uncertainty if your identity is defined by a place that you weren’t raised in? And I guess that goes back to attacking people for the words they use or feeling attacked by people not liking the words you use? That’s a lot of ambiguity and uncertainty to deal with. I think not knowing how you are going to mediate the relationship between yourself and the places that have shaped you is at the heart of the relationship between identity and place for me.

I guess there’s this apprehension to uncertainty and thinking, “How do I change or fix this feeling?”

I would pause and ask, why does this feeling need to be fixed? What is it about it that I think is broken? And then where is this urge to fix it? And so, again, I think it’s sort of like when mixed race people have to explain themselves, they have to tell stories, because we otherwise don’t really have a language for ourselves. Or we’re worried that people might not have the patience for all of our hyphenated self-definitions.

I’m more moved and interested in people who start to tell stories from their own lives, of how they may have heard from their parents about their own survival of martial law, of violence, of election fraud, that they had no idea about before, or their own memory or lack of memory, or something that they wish they knew. I think the telling of a memory or an expression of longing is so much more interesting and the relationship created in the face of uncertainty rather than [making a] statement that tries to eliminate all statements that came before it.

Is it possible to be creative without an audience in mind?

Absolutely. I especially think it’s the case for musicians. You know, I really respect a sense of play in art, you know, people who can be by themselves and make something that they like, without it, necessarily reaching anyone, you know, I respect that hugely. I just find that often impossible for myself. And once again, that might be just a quirk or a shortfall in my own makeup. But to make something for the sake of making something, I think that’s a wonderful capacity that I possibly don’t have. Except when making music mixes for people.