From tales of the culinary to the colonial, these book recommendations invite you to dive deep into Philippine life and literature.

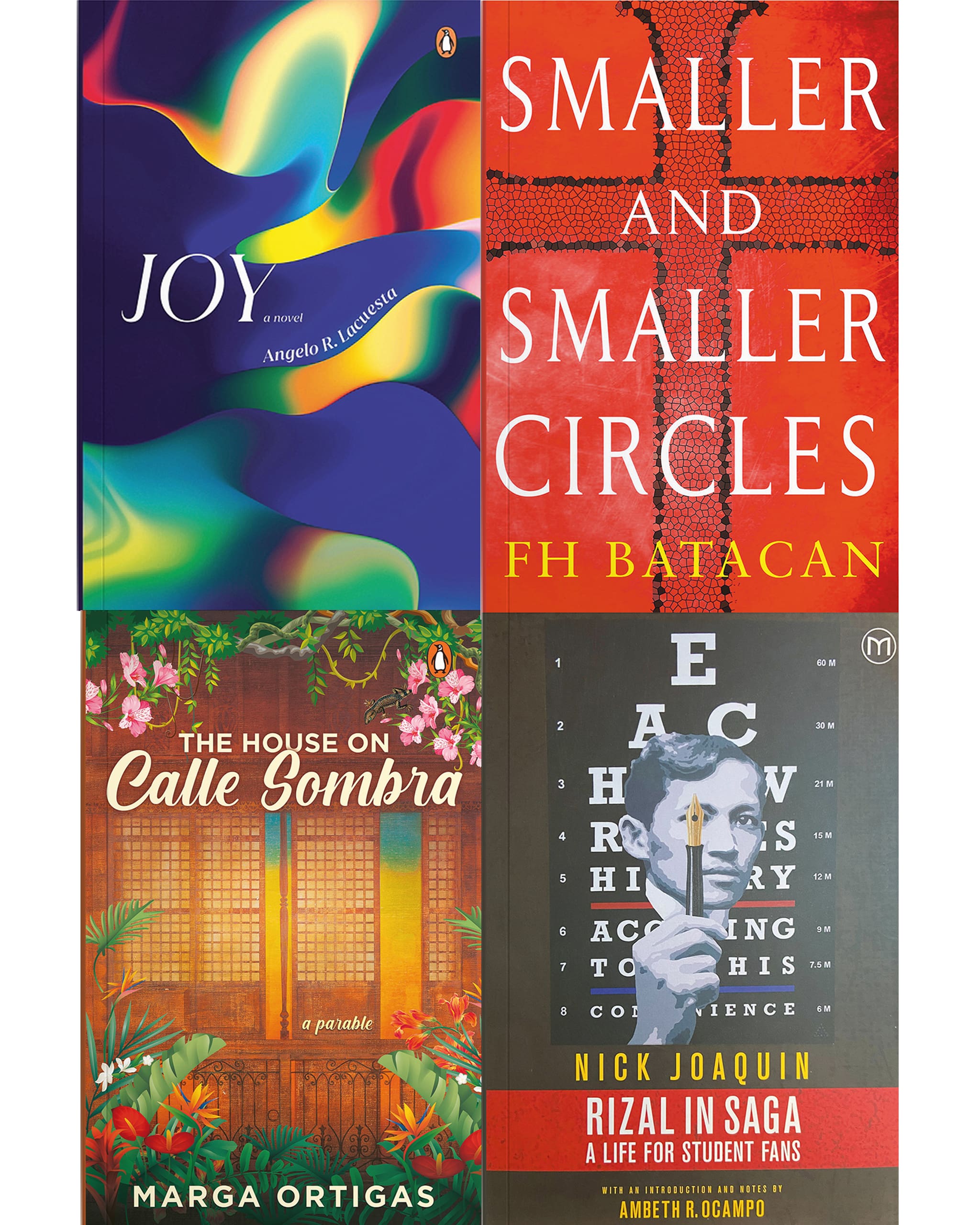

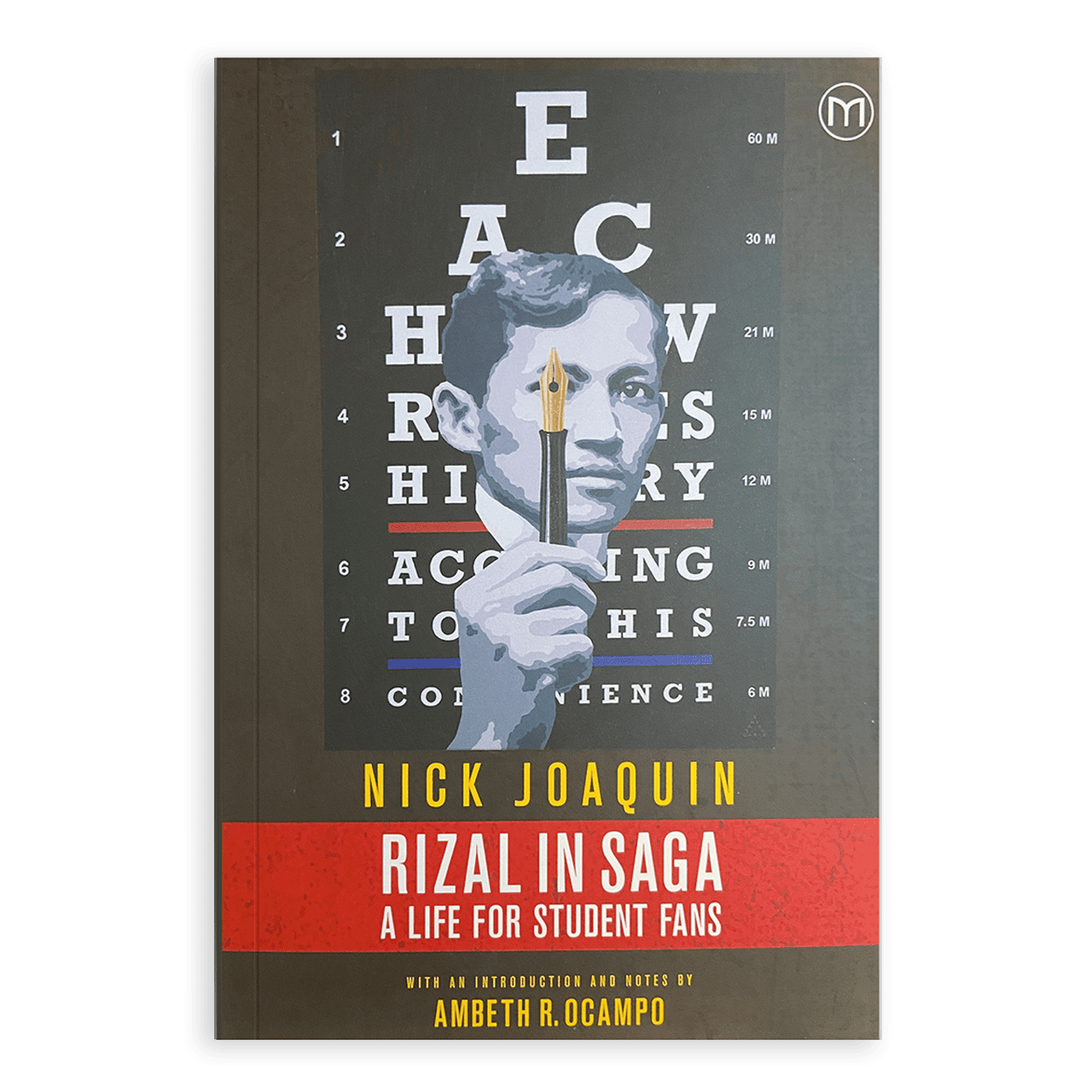

Rizal in Saga: A Life for Student Fans By Nick Joaquin

Nick Joaquin telling Jose Rizal’s origin story across 35 chapters of distinct and lively prose is like listening to the fun tita or tito holding court over dinner around a long table with a sweeping tale.

It’s a mesmerizing read that, for anyone who was taught in school that Rizal was faultless and saintly, makes our national hero far more human, sometimes driven by familial duty or plagued by insecurity, mostly to do with height.

“But our national hero is a shorty armed with a pen and book. Jose Rizal was literally, physically short. Full-grown, he measured about five feet in height, give or take an inch or two. And in childhood he grew so slowly that, on the brink of puberty, he looked like a kindergartner.”

There are four bonus essays at the end of the book, one of which reclaims the heroine of Rizal’s novel, Maria Clara, from the image of frail, cloistered and weak-willed martyr. He begins one essay, written in 1976, with, “Common sense, rarely a shining quality of the intelligentsia, seems to be on even shorter supply during the current egghead assaults on Maria Clara.” His rigorous and energetic defense of Maria Clara as one of Noli Me Tangere’s most formidable characters will make you want to pump your fist in the air.

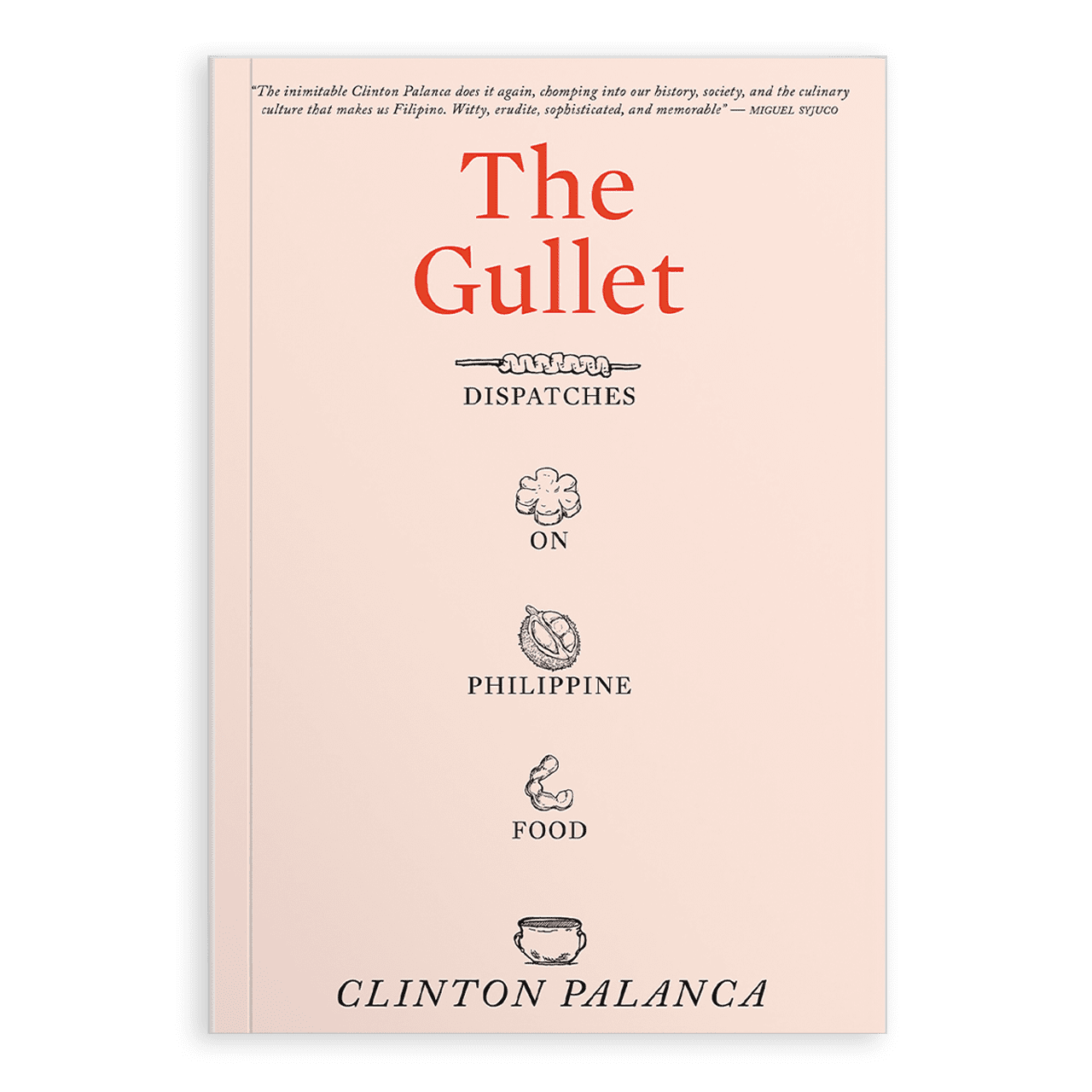

The Gullet: Dispatches on Philippine Food By Clinton Palanca

Before Filipino food began having a moment, there was the long soul-searching that Clinton Palanca captures in this brilliant collection of essays on food and dining. For starters, why isn’t our food as widely celebrated as, say, Thailand’s or Vietnam’s?

In the book’s opening piece, “Bite me, I’m brown and oily,” Palanca considers an often-blamed culprit—that our core dishes simply look ugly and therefore unappetizing—with the help of industry luminaries Amy Besa and Claude Tayag.

But why do we even care? And if we take so much pride in what we put on the plate, why do we need a pat on the back from somewhere across the oceans?

“We want Filipino food to be accepted and admired abroad because there’s so much of us in it, to the point that it becomes a stand-in for how much we are liked and respected abroad,” goes one of his conclusions. It stings in the way that makes you want to say, “right, tell me more” while reaching for a glass of wine.

There’s plenty to chew on in this volume released in 2016 by Anvil Publishing. Every essay is rich in historical context as well as asides from a cosmopolitan life, part of which was spent in England as a student at Oxford.

Here Palanca is equal parts critic and champion of Philippine food, as an industry and a vital feature of the culture, constantly making space for it at the table.

In a light-hearted lament about the end of fine dining and the rise of a more relaxed alternative, for instance, he seats a homegrown establishment beside Heston Blumenthal’s three-Michelin starred restaurant.

“And this is great for most of the year, whether it’s the cozy little dining room of the Fat Duck in England or the bustle of Mamou, where the good steaks start at over P3,000,” he drops casually.

Palanca once prefaced his own TEDx talk with a lengthy explanation on why he does what he does as a food writer when the whole pursuit is neither lucrative nor glamorous.

“I do it because I feel very, very passionate about the Philippine food scene,” he told the audience. “About Philippine chefs, about Philippine restaurants, about the Philippine food industry.”

That passion, fueled by an endless curiosity and informed by a large vat of stock knowledge, shaped his body of work for over 15 years until his death in 2019. His voice at the table has been sorely missed since.

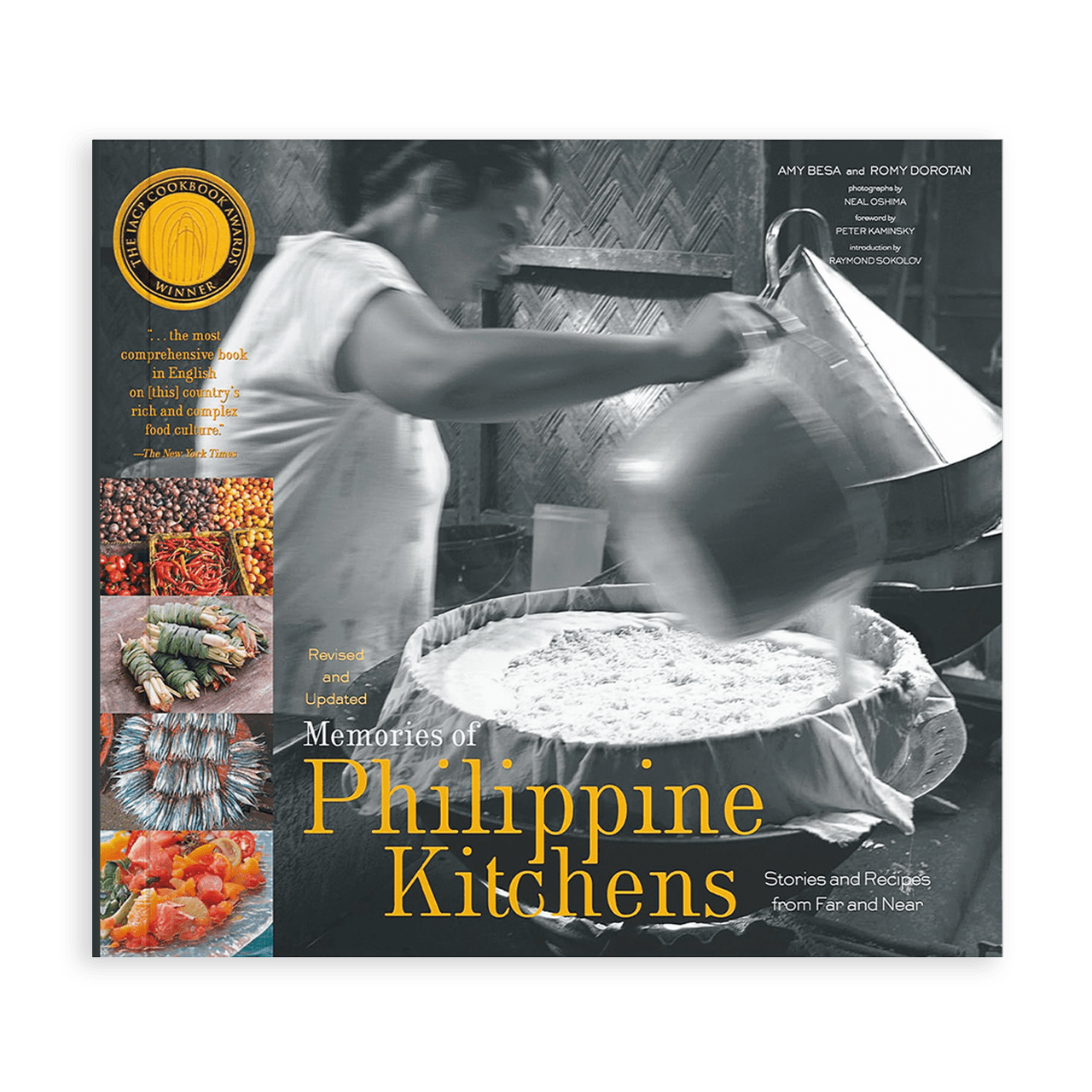

Memories of Philippine Kitchens By Amy Besa and Romy Dorotan

Amy Besa left the Philippines just before Martial Law was declared in September of 1972. She was 21. In all her years of self-exile in the US, food and cooking were always ways of reaching for a home she sorely missed.

“So many good memories and feelings were shattered by martial law,” she now recalls. “But I was able to work my way back and the healing factor and bridge to sanity was my connection with the food. It turned out to be more powerful than oppression and corruption. Food or the love of it in the context of our cultural wealth can overcome anything.”

She and husband Romy Dorotan moved to New York in 1979, where he worked as the lunch chef at Hubert’s on Park Avenue South, and where they soon became part of the city’s vibrant food and dining scene.

They opened their first restaurant, Cendrillon, in 1995 and ran it for 13 years before closing it down in 2009 and decamping to Brooklyn to open their second restaurant, Purple Yam.

But it was while running Cendrillon that they released the first edition of this book. It is a thoroughly researched cookbook, a kind of encyclopedia of Philippine ingredients, and a wonderfully intimate memoir.

The book’s most famous recipe is the chicken adobo, thanks in part to Sam Sifton, New York Times Cooking’s founding editor, who adapted the recipe for his column. But it’s the beef short rib that stands out for Amy.

“It’s the most beloved recipe there. I’ve gotten so much feedback from so many people who have done it,” she says. If you’re turned to cooking lately as a way of emerging back into the world post-Covid, this is a must-keep on the kitchen bookshelf.

The House on Calle Sombra By Marga Ortigas

Marga Ortigas knows something of the collective trauma that binds people to each other, for better or for worse, and how it can hold an entire people captive in a crippling cycle across generations.

“National traumas reappear throughout history in many forms—war, martial law, populist autocrats—the same way family traumas repeat themselves until they are healed or the cycle is broken,” Ortigas says. Her sprawling debut novel, The House on Calle Sombra, published in December last year by Penguin Southeast Asia, might be a work of fiction but it animates the truths about what we inherit and what we unwittingly pass on.

At the center of this cautionary tale/wild ride is the Castillo de Montijo family. Federico, the patriarch, arrives in the Philippines in 1937 as a penniless orphan who then proceeds to manifest his dreams of success into reality.

He marries Fatimah, a native Muslim fugitive, and as they rise to the upper echelons of society, they build a house befitting their stature where they raise four children. If their family motto “family first” has a kind of ominous ring to it, it’s because the book’s larger events echo episodes in Philippine history.

As a broadcast journalist, Ortigas reported real-life stories from the frontlines of armed conflict and natural disasters for over three decades. In 2016, she took a break from the news to pursue a childhood dream of writing a novel. She started by mapping out a family tree and visualizing book covers, making about 20 studies.

Ortigas then spent the next three years writing from 8 A.M. to 5 P.M. everyday, and tweaking all the way until publication date. It’s a deceptively breezy read, with a Spotify playlist to go with it (SOMBRA Sounds). It succeeds in capturing that distinctively Philippine vibe, where the real and absurd are often one and the same.

Joy By Angelo Lacuesta

Joy is a novel told in many different stories, involving a Tinder date, a songwriting contest, an abandoned son, and a childhood sweetheart.

Angelo Lacuesta, who has written poetry, several collections of short stories, non-fiction books, and screenplays all while working as an adman completed this novel, his first, during the pandemic.

Published this year by Penguin Random House SEA, Joy deftly captures life in Manila through his main character’s eyes, from boyhood to adulthood, in episodes that don’t necessarily follow a chronology of time.

These stories, which can be flashbacks, interruptions, or impressions, make the point of life defying neat narratives. What you’re left with is not so much an interest in the details of what happened, but an eagerness to parse out exactly what you’re feeling once you’ve put the book down: nostalgia, perhaps, or an overriding, inexplicable sense of joy.

Smaller and Smaller Circles By FH Batacan

FH Batacan’s evenly paced and consistently riveting mystery thriller is considered the Philippines’ first crime novel. It’s set in one of Metro Manila’s poorest districts, a 50-acre dumpsite that entire communities scavenge for food.

A serial killer is preying on preteen boys and the police are ill-equipped, and sometimes under-motivated, to solve the string of heinous crimes. Meanwhile the body count is rising.

The book’s main protagonists who do most of the sleuthing are Jesuit priests, Father Gus Saenz, a forensics anthropologist, and his protégé, Father Jerome Lucero, a psychologist. It’s not a story you can easily transport elsewhere.

It is also a universally-harrowing tale, not for the faint-hearted. As a searchlight that illuminates the city’s dark and forgotten corners, where the vulnerable have little recourse from the constant menaces of poverty and corruption, Batacan’s first book is fascinating and impossible to put down.

Smaller and Smaller Circles was a shorter but no less compelling read when it won the Carlos Palanca Grand Prize for the novel in 1999 and was first published by the UP Press. Batacan later reworked the novel, keeping her signature brisk and unsentimental but poetic prose, into its current, longer form published in 2016 by Soho Crime, an imprint of Random House.

The following year, it was adapted for the big screen by TBA Studios and distributed by Columbia Pictures.

A version of this story was originally published in Vogue Philippines’ September 2022 issue. Subscribe here.