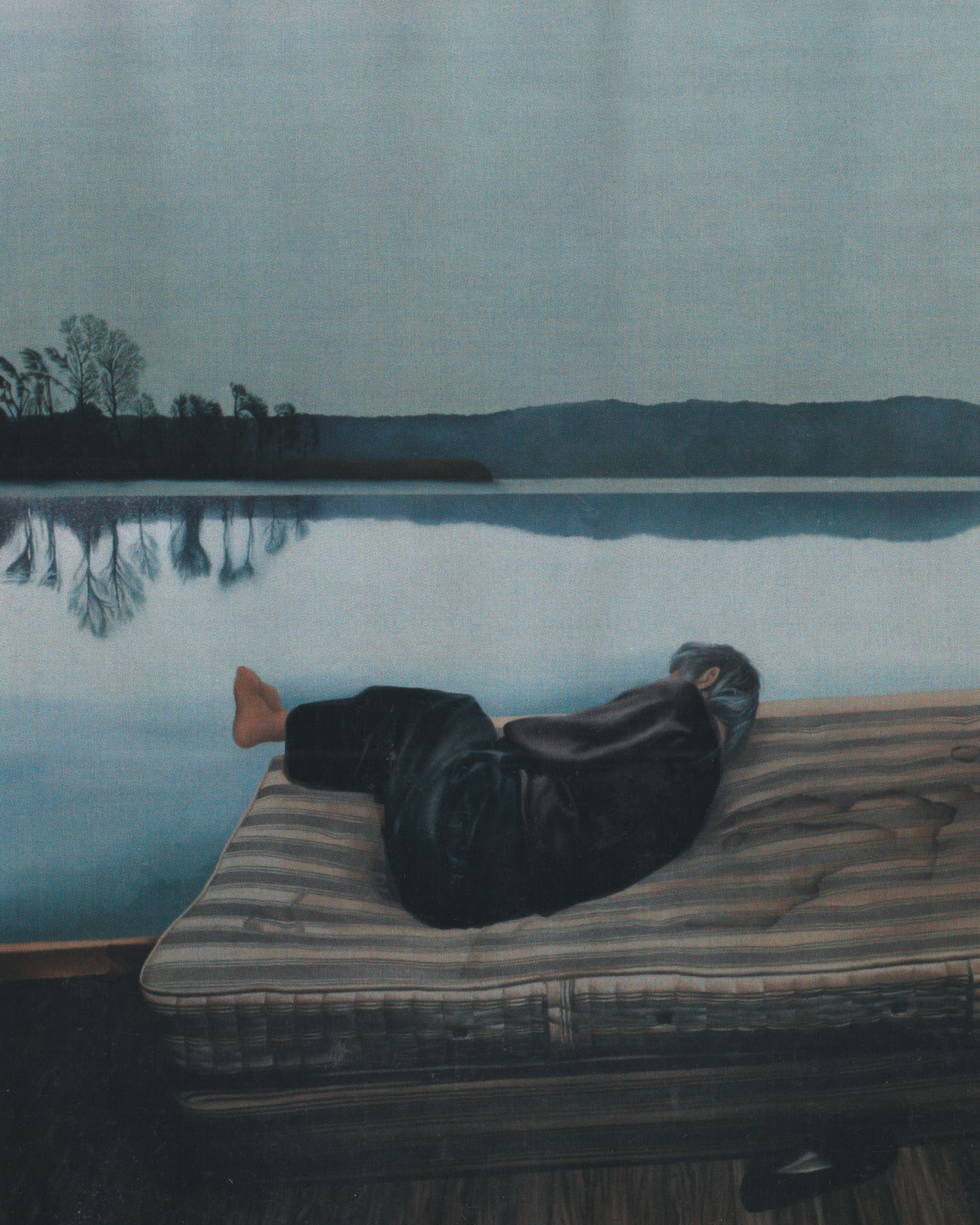

Artwork by Geraldine Javier

As we edge closer to a future where we can medically erase memories of heartbreak, the question is: should we?

“The Wedding Dress,” by Frederick Elwell, a painting unveiled over a hundred years ago, is of a woman dressed in mourning black, with face hidden in the crook of her arm. The open trunk upon which she leans lays open, and wedding dress, shoes and veil are splayed around her. We understand immediately that no groom is present in the room.

You don’t need a vested interest in art to know heartbreak when you see it.

What is not depicted by brushstrokes are the biological effects of acute grief: how at this moment, the woman’s heart rate has hastened, her blood pressure is raised and capacity for concentration lowered, and a dysregulation has settled into her sleep patterns and appetite. She is, in the 24 hours after the death of her spouse, almost 28 times more likely to experience a heart attack than in the six months prior to his passing. With time though, most people will adapt to heartbreak; the edges of pain will soften, and other concerns of life given mental real estate that have, for months, belonged to the loss alone. For some one in ten people however, six months to a year from the first instance of heartbreak, the experience of grief transforms into almost something else entirely.

Though it seems counterintuitive, humans may resist healing from that which must be processed in order to remain in some way connected to the person we loved. This makes way for that which psychology has named “complicated grief.” We oscillate between the stages of denial and bargaining in perpetuity. Remember Jim Carrey taking Kate Winslet by the hand in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, running through his memories in search of somewhere to hide the two of them; under childhood kitchen tables, in and out of their apartment as the rain of their dissolving relationship threatens to wash them away. There won’t be anyone left to remember it if I don’t, grief says. So come here, where the healing can’t find us—I’ll keep us safe.

“Not all emotion is created equal; complicated grief can arise when we have had a history of not being able to fully express our emotions, so they get stuck in a kind of loop, where we stop ourselves, sometimes unconsciously, from fully recognizing our feelings of loss,” Mitchell Smolkin, a Sweden-based psychotherapist whose work largely focuses on finding dignity in suffering, explains. “This is often characterized by uncontrollable crying and/or intrusive thoughts that we cannot stop and that do not move in waves between feeling intense sadness and feeling better.” He shares that often a loss later in life, such as from the end of a romantic relationship, can feel extraordinarily intense because it breaks the dam holding back earlier grief that was never felt. It is no wonder that we should desire to rid ourselves of such an experience.

History is littered with remarkable and often horrifying attempts to forcibly rid ourselves from the impact of complicated grief, the outcomes of which are inconsistent, if not overtly harmful.“The extreme forms of interventions—such as the damage done historically by lobotomies—could sever the person from their personality and cause them to lose the fullness of their emotional lives,” Smolkin explains. “Electroconvulsive therapy or ECT is a controversial contemporary treatment that is used in the most dire of situations, with major personality disorders and certain forms of psychosis.” He recounts his own experience with patients in the hospital, seeing a marked change in their personalities, including the erasure of parts of their identity. “Electric currents are sent through the brain and this can result in a literal loss of memory.”

Still, as has often been the case with innovation, time and the efforts of a dedicated few has seen positive developments in the science of forgetting. As recently as 2017, researchers from Columbia University and McGill University published a study that indicated it may be possible to develop drugs “to delete memories that trigger anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, without affecting other important memories of past events.” The experiment consisted of blocking Protein Kinase M or PKM molecules, weakening the neural connections responsible for the strength of associative and non-associative long-term memories. Though only conducted on snails thus far, humans possess similar PKM molecules, so a future where we can block memories of heartbreak may not be so distant. The question is: even if we could, finally, decisively and effectively do such a thing, should we?

“Neurophysiologically, the full expression of our emotions is very important, to be able to get to the end of how we feel,” Smolkin asserts. Though we may be tempted to live in a cycle of rumination and bargaining—or otherwise seek relief by medically eliminating the memory of heartbreak—the hardest yet kindest thing to do for ourselves is to choose to process our loss. Rather than run through our childhood memories, planting evidence of a loved ones’ existence so we may not forget them in our healing, reprocessing the traumatic events from our past that may have contributed to our complicated grief in the present, has been shown to offer a way out of our suffering. The bereaved needn’t fear forgetting love: “If anything, [therapeutic intervention] increases remembering, as the experience becomes three-dimensional, and dare I say it, pleasurable to remember, in the sense that the sadness shifts into meaning, and however difficult the end of a relationship was, understanding emerges both about oneself and the other person.”

If grief as art is an inconsolable widow, body slumped and slack, gentle sadness and her sister, acceptance, may be a James Turrell art installation. The American artist’s immersive artistic and architectural creations dot the globe over, among the most recognizable being rooms or spaces with an opening in the ceiling that frames the open sky, gently guiding the audience’s faces upwards. “Gradually, the fringe of cloud will expand and drift across the aperture; the light will fade. Rain might even fall. But the concern is not only with what we see,” philosopher Alain de Botton co-wrote in his Art as Therapy. “The search is for a profound individual experience, but one that others are also having.”