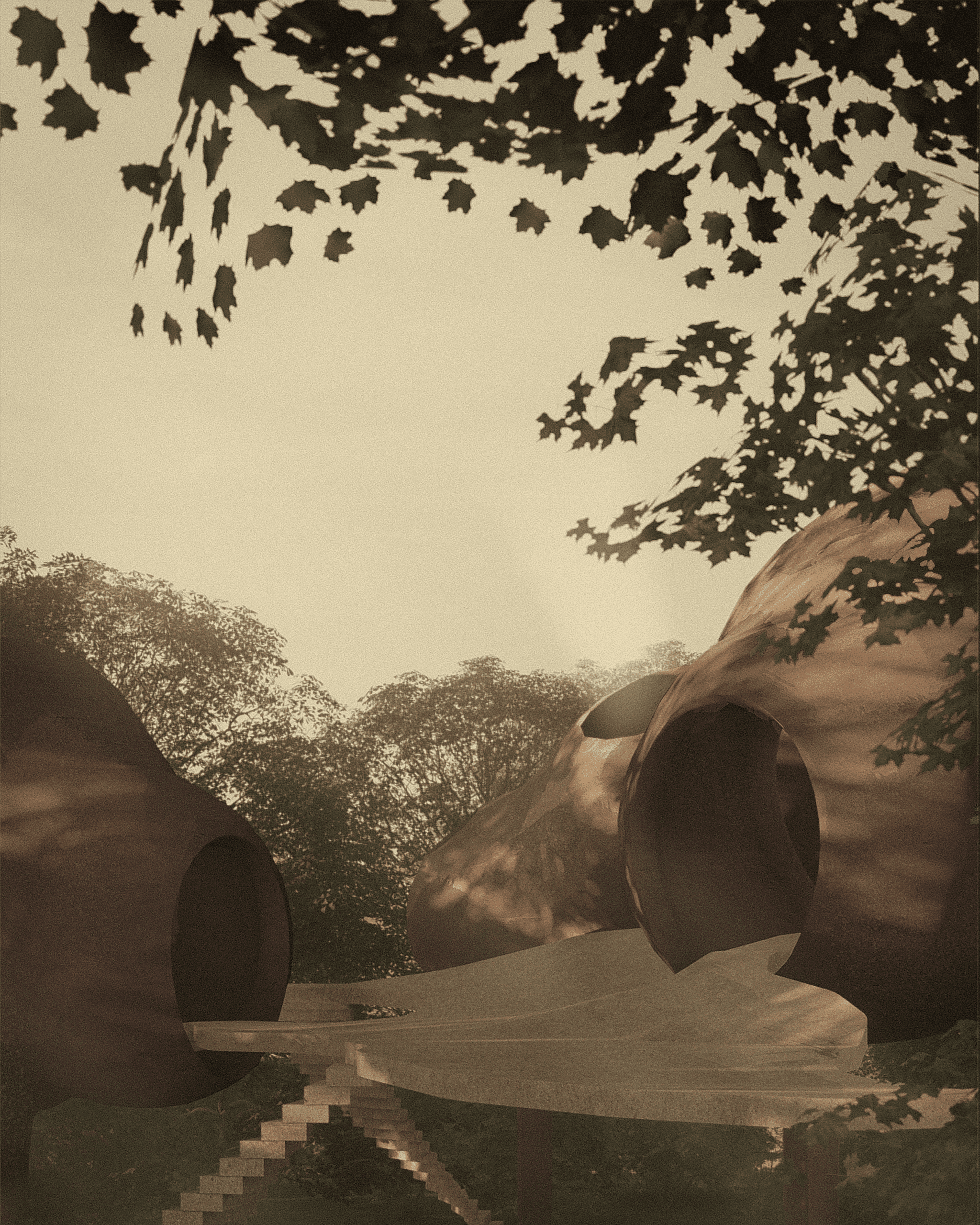

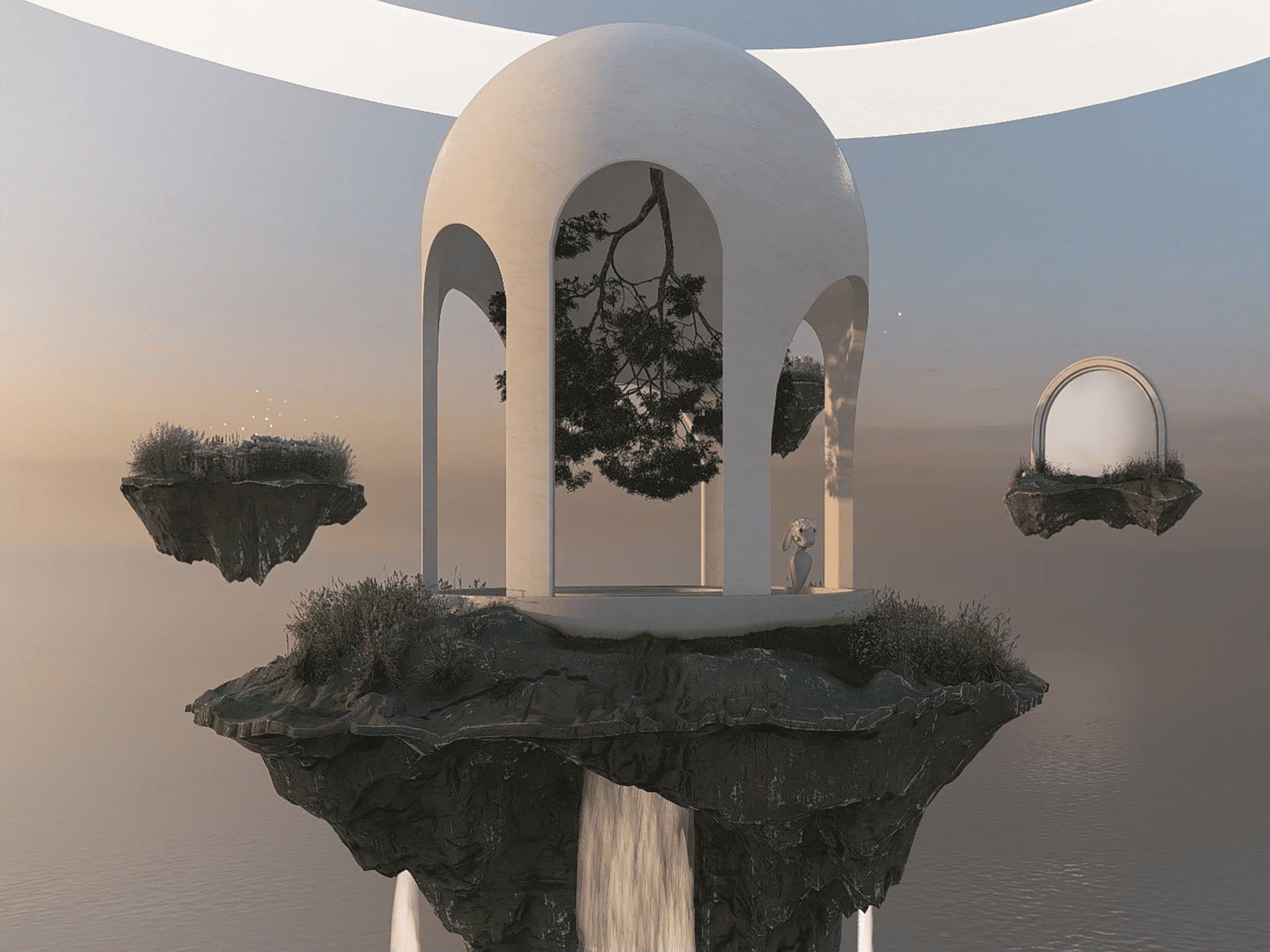

Somnium Treehouse. Image courtesy of Bianca Carague

“I started out designing objects, or ‘artifacts’ … Eventually, I began making whole worlds.”

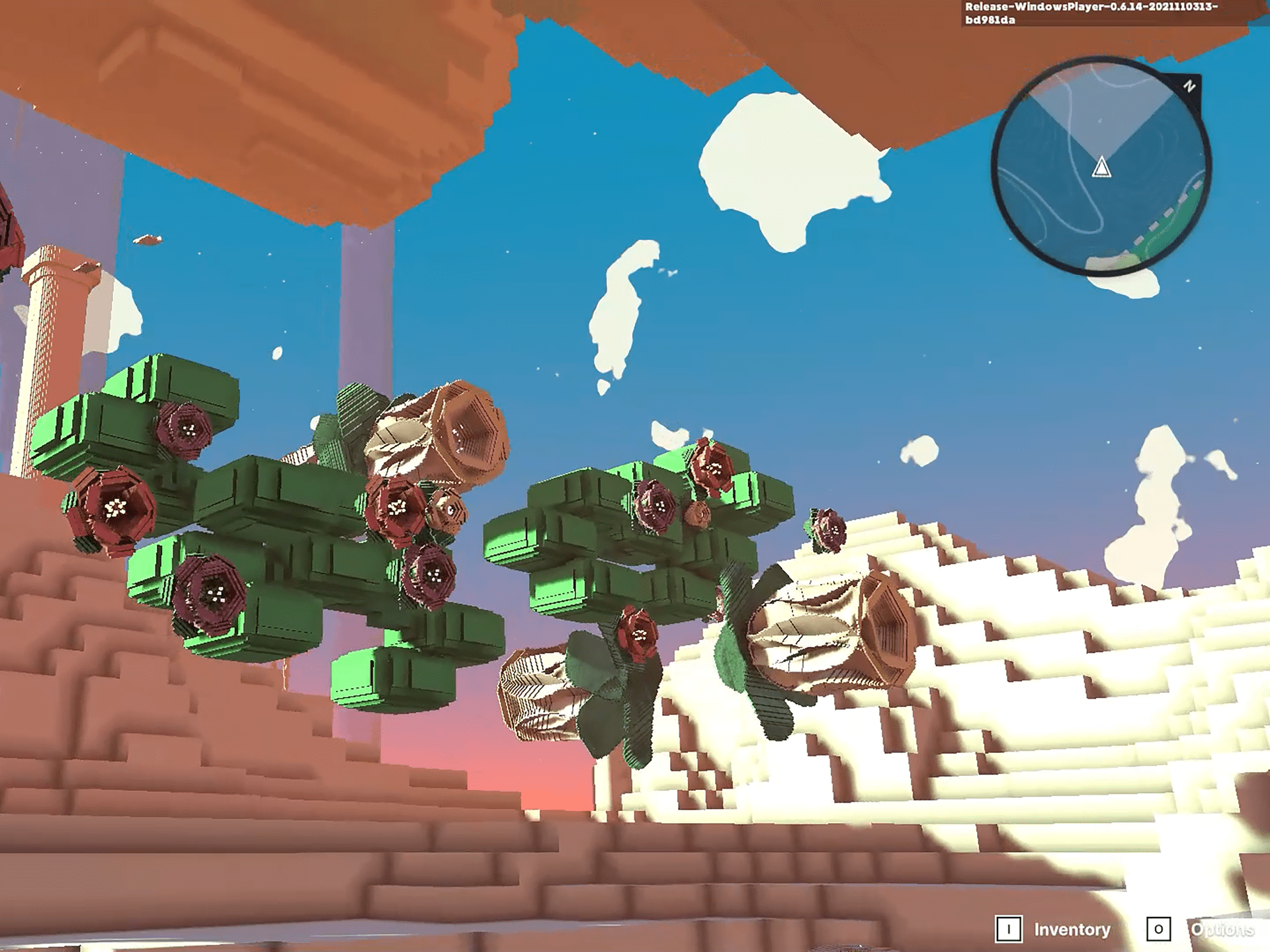

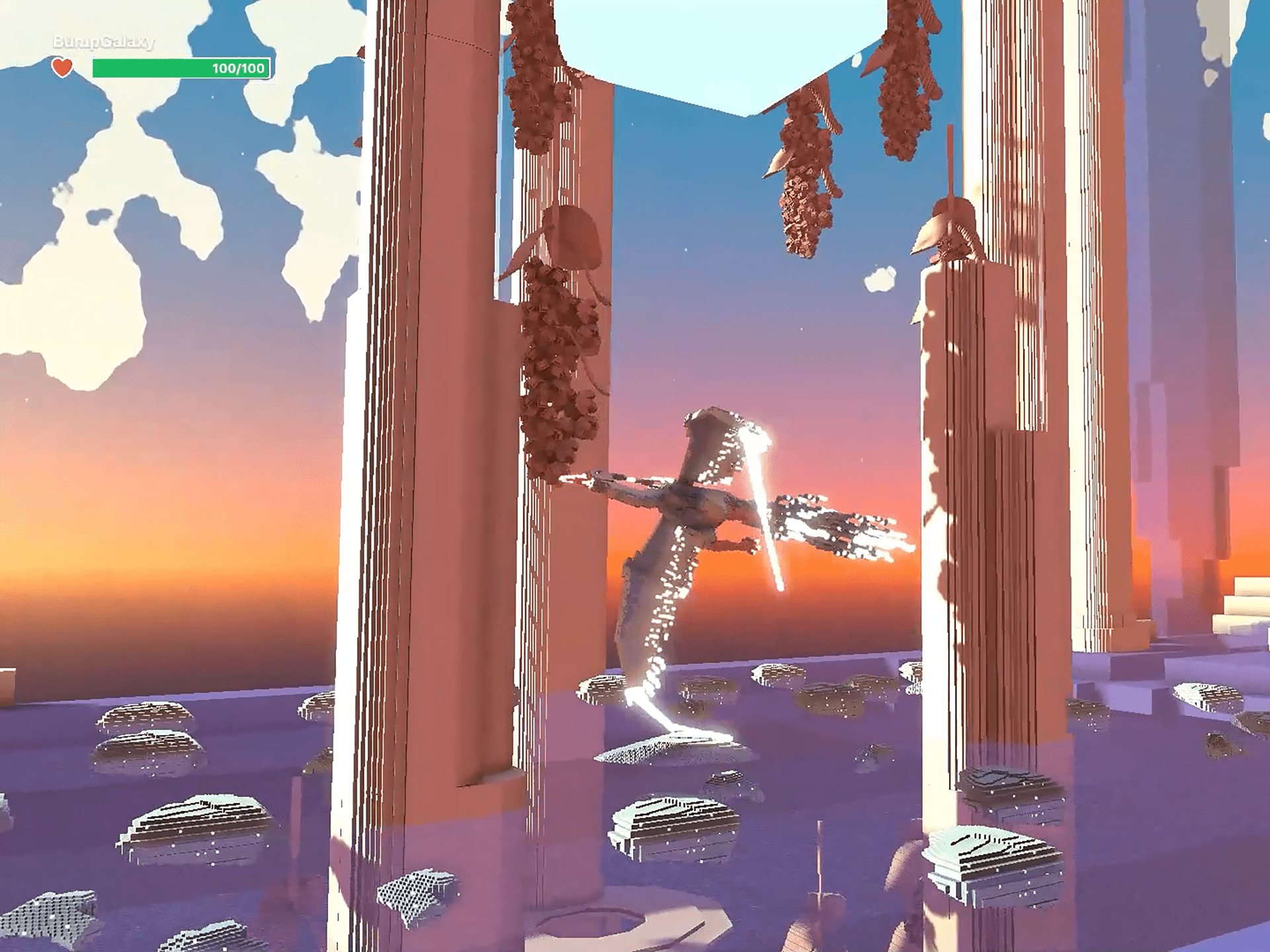

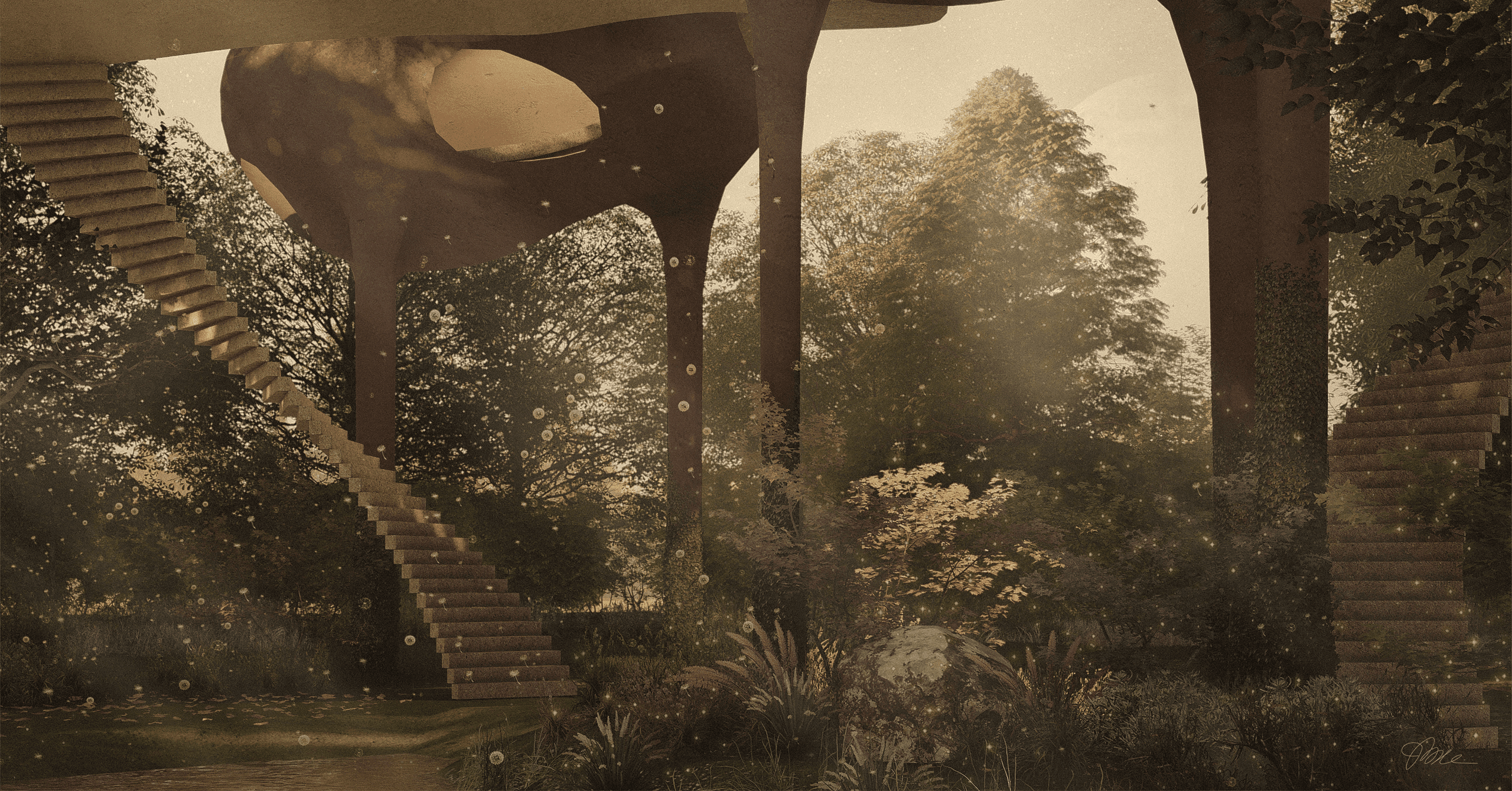

Entering into the virtual realm Bump Galaxy, one might encounter a sparkle of fireflies that asks how you’re doing. Glowing avifaunas soar above head, dancing between pixel-made parrots. Heartfelt conversations with strangers are even highly-encouraged. “Welcome to a place in the metaverse, where people play to care,” reads the welcome message as one enters the digital space. This is social designer Bianca Carague’s Bump Galaxy, an interactive virtual space for mental wellbeing.

When the pandemic hit, mental health issues were pushed to the limelight as countries began imposing strict lockdown protocols. “Sometimes we feel like [healthcare] is scarce because therapy or medication is expensive, and there aren’t enough people to provide it,” she says, adding, “So it’s about activating multiple capitals, like community and creativity, to create a culture and mindset of abundance around care.” Frustrated, one unlikely solution has been proposed by the Filipina social visionary: why not create a virtual world where users can access meditative spaces and receive joint therapy from specialists around the globe?

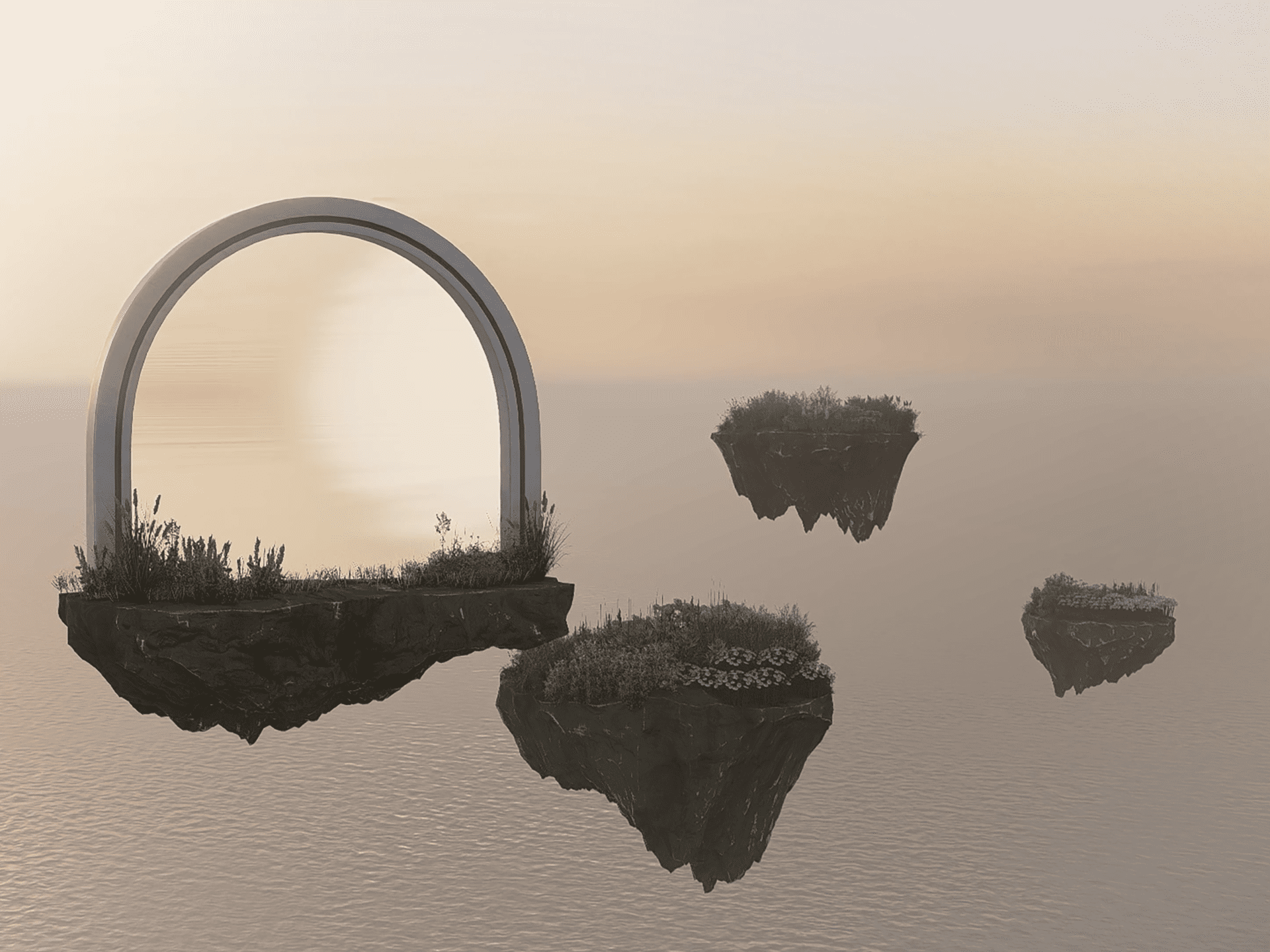

Inspired by the concept of “digital therapeutics,” Carague built online sanctuaries where anyone—from Minecraft gamers to metaverse explorers—can immerse themselves in serene surroundings, build community if they choose to, talk to licensed mental health professionals, and just feel less alone. “It helps to just hang out if you’re isolated and feeling lonely,” she muses.

Calling the creative process “fun” and “meaningful,” she continues, “I figured that making worlds was an immersive way to invite people to see the world as you do or imagine what the future could hold. It’s a nice way to propose—but not impose—alternatives to current systems, existing solutions, and ways of living.”

Even when she was a furniture designer in the Philippines, Carague found fulfillment in community and later decided to pursue her Master’s degree in Social Design from the Design Academy Eindhoven. Rather than create for consumption, or for luxury, social designers aspire to leave a positive impact on society or to address complex social issues and these days, the Netherlands-based designer focuses on issues of public health and climate. She even mounted a solo interactive exhibition entitled “Gen C: Children of 2050,” which presented four types of kids we could be seeing in the future. More recently, her focus has been on Futures Literacy and Worldbuilding and her work with Bzaar Labs, a digital fashion company that builds 3D design software meant to enable users to develop their own clothes.

“I started out designing objects, or ‘artifacts’ that would embody a certain speculative scenario I came up with as a reaction to a social issue. Eventually, I began making whole worlds.” Vogue speaks to Carague to uncover how a digital future might actually be the key to our mental health and wellbeing.

In what ways can virtual spaces be used for mental wellbeing? Is this something that we might be able to see in the near future or are we still a little ways away from it?

There are several. The first one is that, like meeting up with friends physically, congregating online can give us a sense of community and belonging. We’ve seen this in places like Roblox, Minecraft, and World of Warcraft, especially during a pandemic. It helps to just hang out if you’re isolated and feeling lonely. And online, you can make friends from all over the world.

On that note, I think that when people think of virtual spaces, they first think about video games, which in the past didn’t exactly have a good reputation when it comes to mental health. But people actually do make games specifically designed for wellbeing. These usually fall under the digital therapeutics category and can range from mobile games to immersive VR experiences.

In these games, the environment and mechanics are designed to help players develop skills to deal with real-life scenarios and things like anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Virtual spaces affect our well-being just like our built environment does. But what I find special about virtual spaces is that you can experience things unheard of in the physical— like falling from the stars or swimming with glowing birds.

If virtual spaces were to become a regular part of our life, how do you think that would affect our social dynamics?

People get treated differently in the physical world all the time. Often, this has to do with how they look or where they come from. But since people show up as avatars in virtual spaces, they can have multiple identities and show up however they like or however they feel safer. I can be taller, I can have silver hair, I can be a blob, I can wear water. That’s the positive side, but with online anonymity, we also need to think about safety.

Unsurprisingly, status symbols exist in virtual spaces too—like what clothes you’re wearing or what NFT you own. Sadly, kids who can’t afford premium skins have been bullied for wearing something basic in games like Roblox. There are many nice things that come with being able to freely express yourself virtually, but ideally, people don’t feel left out.

The Somnium Treehouses were really striking to me. Could you talk more about that space and how it’s meant to be interacted with?

When I first joined the platform, everything built in it had sharp geometric edges, high-contrast, dark [and] neon colors—very intense and cyberpunk, as you can imagine. Personally, I prefer online spaces that are more soothing. The Somnium Treehouses I designed to feel like a mother’s womb—like a warm embrace, hence the shape and color.

If you visit it in [virtual reality], you’ll see that I also put different floating question prompts inside the womb-like structures. It’s similar to the snowfield in my (Bump Galaxy) Minecraft server—you can leisurely walk around and find floating question prompts about love and life, which you can ignore, but my hope was that people would use them to have meaningful encounters or conversations with strangers online.

Was Bump Galaxy conceptual or was it able to be used by the public? If the latter, did you receive any feedback about users’ experience with it?

It was a little bit of both. It’s not (yet) natural for different genres of mental health professionals to collaborate in real-time in a gaming environment. And Bump Galaxy was my way of putting that idea out there. But it was also used by people.

We’ve done some drama therapy sessions with kids on the floating drama therapy island. Most of the time, kids are better at playing Minecraft than their therapists, so we saw them become more confident, assertive and engaged than usual.

We also did group meditation sessions in the meditation forest with people from around the world. The first group that visited [was] actually a bunch of designers from SONY Japan to learn more about wellbeing online. They loved it and it was really cute!

What element or area in your virtual spaces resonated with you the most and why?

Honestly, anything that floats or glows I love. I very much like the magical quality that online spaces can have. Gaming mechanics add to this magical feeling as well. In the meditation forest in Bump Galaxy on Minecraft, people could plant a small tree sapling before they start their meditation. When the meditation is over, they could open their eyes and find that the tree has fully grown.

This kind of cognitive association we could create between the forest and people’s progress on their wellbeing was nice to have. I personally like to have rituals and symbols in my daily routine because they make otherwise invisible progress I’m making more tangible.

The Somnium Treehouses are on parcel #2129 in Somnium Space via VR. Updates about Bump Galaxy can be found on their website.