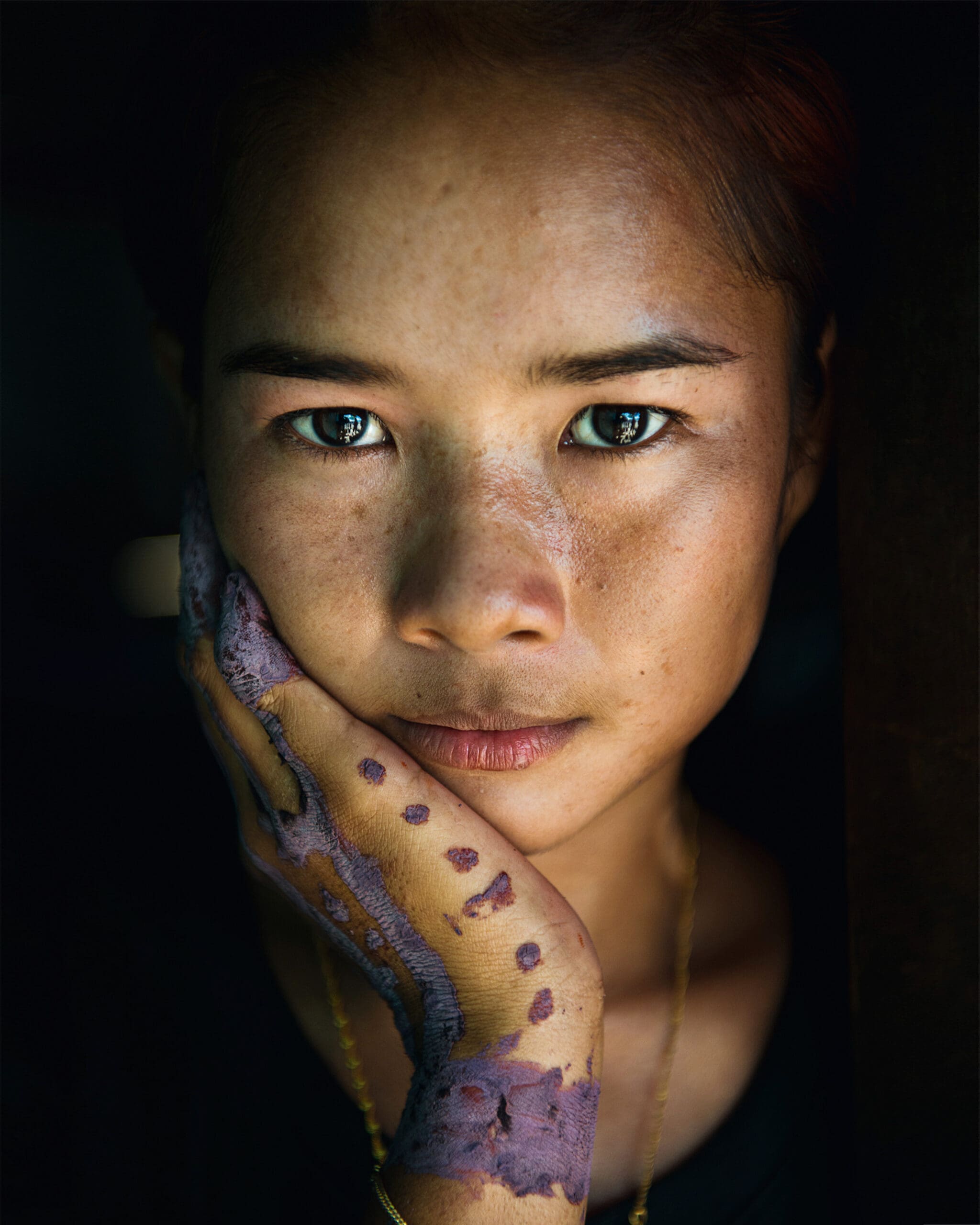

Photography by Jacob Maentz

A Sama-Bajau woman on her wedding day with henna tattoos used on both the bride and groom to signify their bond together. Photography by Jacob Maentz

In praise of indigenous self-care.

Clean beauty regimens may be au courant, but natural ingredients have always led the way in the archipelago.

Before the arrival of colonists, Indigenous peoples made their home in the heights and depths of the land. They picked what was naturally abundant, taking just enough to nourish and heal themselves. Beautification was in the wings of protection, or healing.

Take turmeric paste. On the Internet you might see women of the world whipping up the bright yellow face masks in their kitchens, touting the natural glow it gives them. But for Sama-Bajau women in the island province of Tawi-Tawi, it’s a natural sunblock.

This was documented, among many cultural treasures, in Homelands: Indigenous Lives in a Changing Philippine Landscape, the substantial tome that emerged from photographer Jacob Maentz’s years of observing and immersing with various Indigenous communities in the Philippines. Following his images are essays by Nicola Sebastian, as well as layers of voices, interviews, and oral histories springing from the thought that “every island is a world all its own,” as Sebastian writes. Flipping through its pages makes one sit up in awe of Philippine landscapes, coasts and forests, and see what we are losing to aggressive miners, loggers, and developers, which is the major tension of this book: we have to restore the balance of nature.

In this, our spirit guides are the Indigenous people. In lands owned by Ifugao clans, for example, “You can cut trees to build a house or for other uses,” says Tyrone Beyer, from the province of Ifugao, “but you need to plant more trees so there’s no barren land.”

Jocelyn Alejo, an Ayta woman, says, “The forest is our market and our pharmacy; we have access to it all the time.”

In the same way that stories and markings on the body are vital lines of transmission in small groups, healing rituals pass down a culture of care in communities. Many Filipino villages have their own herbolarios—healers who administer poultices, concoctions and teas made out of herbs, and become deeply respected in their locales.

In fact, their know-how has become a source material for medicinal research in the country. The Philippines has an official body called the NIRPROMP (National Integrated Research Program on Medicinal Plants) and it has been studying local herbs used as remedies for the common cold, fever, and headaches since the ’70s.

At the time, Philippine pharma was spending approximately 150 million pesos every year to import medicine for such frequent maladies. The team successfully isolated vitex negundo, a hardy, five-leaved aromatic shrub with bluish-purple flowers, used for hundreds of years to treat wounds, headaches, ulcers, skin diseases, diarrhea, and the common cold, in order to develop clinically proven cough and asthma medicines that are locally produced. Other studies followed.

The same model could apply to validating herbs traditionally used for cosmetic purposes, such as turmeric, whose bioactive component curcumin is said to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, and in a recent American study, potential to combat UV-induced cellular damage and oxidative stress. However, commercializing the fruit of that research must be done in balance with the environment.

As Ruel Bimuyag, an Ifugao, says, “We need our culture to remember. We need to remember to know who we are, today. We need to remember to stay connected to the land, to know how to take care of it.”