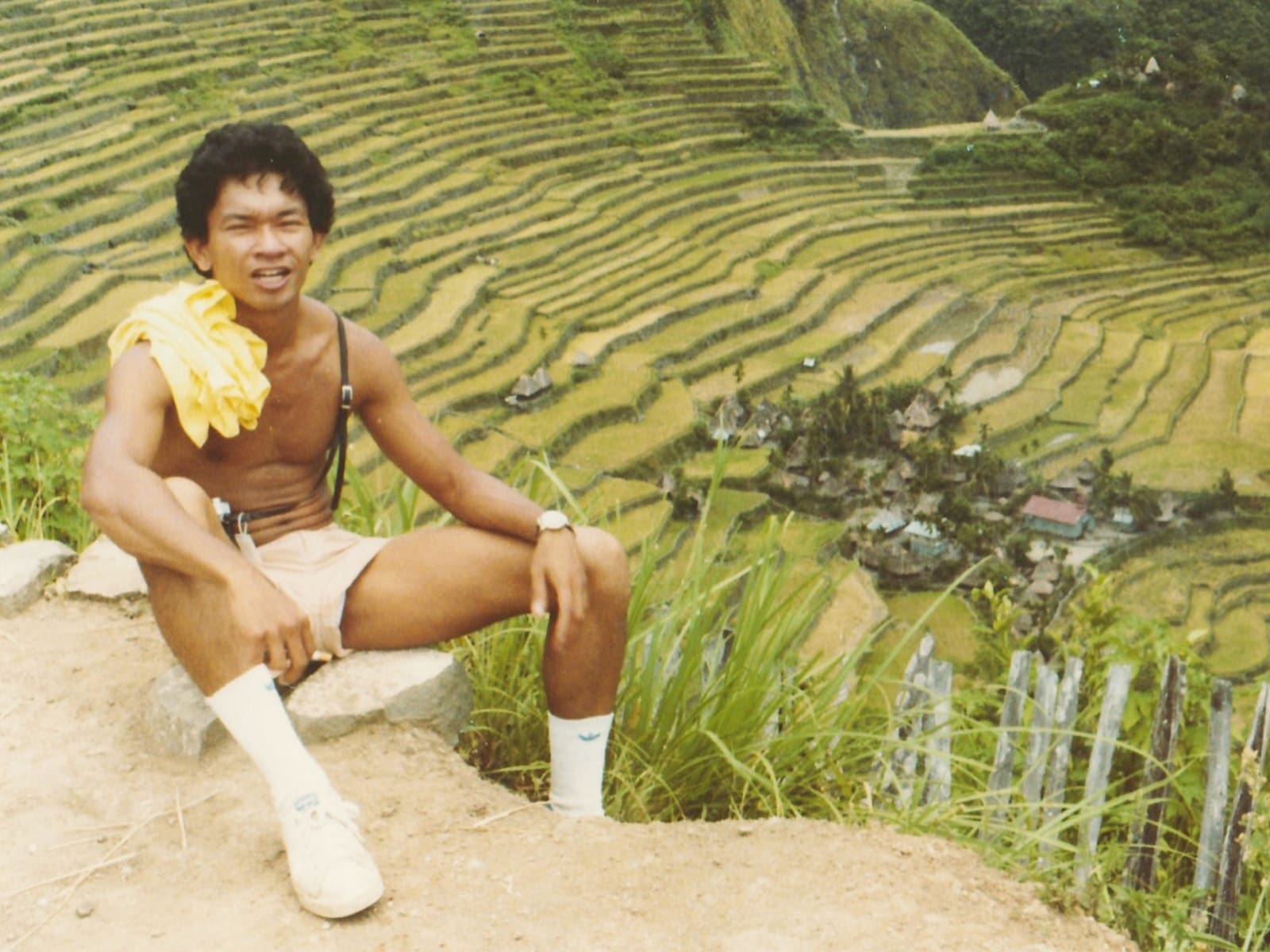

Angel Lontok Cruz on his travels throughout the Ifugao region. Photo by John Chua

Rare bu’lul and tapestries of the Cordillera from the collection of Angel Lontok Cruz highlight Leon Gallery’s Magnificent September Auction

Authenticity, quality, provenance—these are the three hallmarks of a good collection, qualities that a discerning collector has in their checklist of great art. In what seems to be a providential intervention of the mighty hands of the ancient gods of the land, all these attributes are embodied and manifested in a rare selection of important Indigenous art from the Philippine Cordilleras and the Visayas in Leon Gallery’s “The Magnificent September Auction,” happening on September 9th.

“The enigmatic collector Angel Lontok Cruz has determined that this is the right moment to share some of his most extraordinary indigenous art,” Leon Gallery director Jaime Ponce de Leon remarks.

The items in this selection come from the collection of Angel Lontok Cruz, a noteworthy name in the sphere of Cordillera art collecting. Cruz forms part of a distinguished triumvirate comprising the equally esteemed Ramon Tapales and the late David Baradas, all honored as the earliest serious collectors of Cordillera art.

Cruz’s bu’lul and indigenous textile collections are among the most coveted lots.

According to Floy Quintos, a leading expert on Philippine Indigenous art and culture, the objects gathered here embody the three qualities by which these arts are judged by international connoisseurs and dealers of the trade in Indigenous Art (also called Arts Premiere or Arts of the Indigenous Peoples.)

Cruz kept his remarkable bu’lul collection in Amsterdam for over three decades. “These objects were just recently repatriated to the Philippines. As ethnographic objects, each one represents the highest cultural and spiritual ideals of the peoples who created and used them,” continues Quintos.

Cruz’ Hagabi, the Ifugao prestige bench, was auctioned last year for a staggering price of nearly PHP 20 million, the second most expensive sold at any auction. It was described as “the king of the hagabis” by none other than William Beyer, the son of Henry Otley Beyer, foremost scholar on Philippine indigenous culture and “Father of Philippine Anthropology.”

Cruz is described as a very lowkey man, bearing that “folksy charm and dignity of a provinciano, which he proudly says he is,” as Quintos puts it. Descended from the affluent Cruz and Lontok clans of Bulacan Province, Angel first came across Philippine indigenous art during his Architectural Engineering studies in Europe when he visited the gallery of Rob Kok, considered one of the first foreign collectors who actively promoted Philippine indigenous art abroad. Succeeding visits to the Leiden Museum and the Musee de l’Homme in Paris were also catalysts that birthed a unique sensibility in Cruz: being “enamored of the severity and power of Cordillera art.”

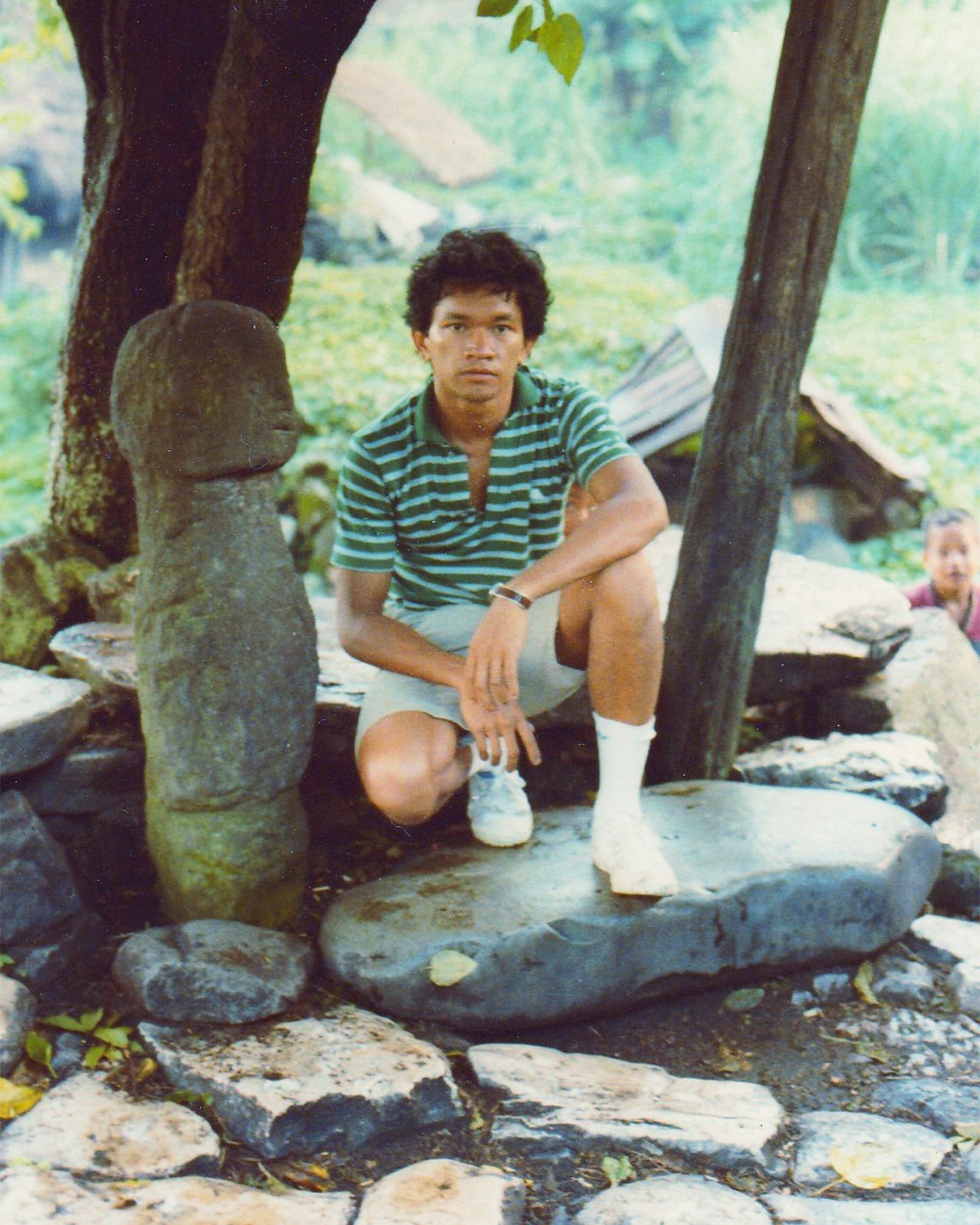

When he came back to the Philippines, Cruz traveled extensively throughout the Cordilleras, specifically in the provinces of Bontoc and Ifugao, to profoundly immerse himself in the culture, traditions, and norms of the Cordillerans, whom he deemed as the creators of “the real art of the Filipinos.”

Cruz writes in the Leon catalog: “What has always lured me to the art and objects of the Ifugao and the Cordilleras, besides some natural affinity, is a sense of rediscovering remnants of an original authentic native world, a developed civilization with its own language, social and political hierarchy, a mountain economy, its own system of justice with communal laws and rules, its own religion and rituals, and with a distinct art and even architecture. The objects tell of a time when we were still our original selves, not Hispanized nor Westernized. They remind us in a way of who, as a people, we once were and truly are.”

Cruz’s collection has now encompassed virtually all aspects of the Cordillerans’ tangible cultural heritage: bu’lul figures, architectural components and adornments, and even everyday objects, such as spoons and bowls. He formed connections with foremost dealers of indigenous art in Baguio and Manila and forged a deep friendship with Ramon Tapales, who sold him the above-mentioned “Beyer hagabi.” “At that time, there were very few Filipinos who were interested in Cordillera art. There was more camaraderie than competition between the likes of Ramon Tapales and myself,” reminisces Cruz.

The oldest of Cruz’s bu’lul figures—a maternity figure, dates to the late 18th-century. Three of the most prominent in Cruz’s trove are a seated bu’lul from either the towns of Lagawe or Kiangan in Ifuago, the aforementioned maternity figure from Banaue in Central Ifugao, and a large and important Tinagtagu/Gal-Galawen/House Guardian of the Kankanai.

The first one—the seated bu’lul dating back to the late 19th to early 20th-century, notes Quintos, was once owned by the eminent Ramon Tapales and is described by him in his 2014 memoir as having “a natural patina and crude but powerful carving style.” Quintos then tells of an interesting story behind this bu’lul. An American collector saw this bu’lul in Tapales’ Quezon City abode and took interest in it. The former asked to borrow the piece overnight “for study,” to which Tapales reluctantly agreed. Tapales would retrieve the bu’lul after a few days, only to find out that that American collector had run away with the piece and flew back to the US. Tapales sued the American collector, who in turn ended up paying USD 5,000 for the piece.

This bu’lul would soon be offered to Cruz and it has since remained one of his favorites in his collection of indigenous artifacts.

The second, depicting a maternity figure and dates to ca. late 18th- century, belongs to that rare cluster of Ifugao maternity figures since “the theme of motherhood is more commonly found in spoons and some other household objects.” Its original Ifugao owners reckoned its age at seven generations or 175 years.

The third one, a Tinagtagu from ca. mid to late 19th-century, is an anthropomorphic sculpture found among the Kankanai people. It is “commissioned when a couple builds their first home” and is highly regarded as a house guardian. Quintos says about this significant piece: “This large and important piece shows all the characteristics of Kankanai sculpture. The torso, arms, and legs are rounded and fleshy, and the face is detailed and made more animated by cowrie shell inlay for eyes.”

The most distinctive feature are the tattoo marks etched onto the arms. The honeycomb designs are consistent with the tattoos worn by successful Kankanai warriors who had proven their valor as headhunters. The designs extend from the wrist and continue on the upper arms. These motifs are also shared with the neighboring Kalinga.

“While many Tinagtagu may represent a generic house guardian, this particular piece brings to his guardianship, the fierce reputation of a warrior who had earned the right to wear a full sleeve of tattoos.”

Quintos describes that the Ifugao anthropomorphic sculpture of the bu’lul has become an iconic symbol of Philippine culture, and thought often called gods, they are not a deity worshipped in the way we would imagine. “Rather, the wooden images are receptacles for the bu’lul spirit invoked to attend and witness rituals. Although most simplistically referred to as guardians of the rice, they also fulfill other functions, as mediators in healing rituals, as witnesses in the ceremonies of social ascension. In order to propitiate the bu’lul spirit that is called to inhabit them and gain their favor, offerings of rice wine, meat, and the blood of sacrificial animals are offered, the last liberally doused or smeared. This mutual exchange of protection/witness/ attendance in return for food is detailed in the myth of Humidhid, the first carver of bu’lul.”

Another important rarity in Cruz’s trove is his collection of two tapestries from Miag-ao, Iloilo Province. Venerated and much acclaimed as the “Grail of Indigenous Textiles,” these tapestries, which date back to the late 19th century, possess a rich provenance. They were first found in Iloilo City in the mid-1980s by top dealer-collector of Indigenous art Rolando Go, who counted among his clients Tapales, Baradas, Lontok Cruz, Joaquin Palencia, Ramon Villegas, and countless French and American dealers.

with Dancing Figures and Animal Motifs. Photo by At Maculangan

Go purchased the textiles from the shop of Lourdes Dellota, whom Quintos describes as a “legend in the field of Philippine antique dealing.” Quintos narrates that Go found one of the textiles being used as a mantle on a table loaded with santos. “Because of the condition, Roland bought it for a song. I remember him telling me that, in his excitement, he hired a jeepney to bring him to Miag-ao. There, he walked around the town, blanket in hand, asking random locals what they knew about it. His Eureka moment came when he espied, hanging on a clothesline, a near-perfect example which he bought on the spot.”

“He was told that these textiles used to be very plentiful and were produced in Miag-ao (to this day, still a premiere weaving center for hablon). They were not blankets but tapestries that would be hung from the windowsills during fiestas and special occasions. However, he was unable to find any more.”

Among the numerous items in his collection, Go cherished these two tapestries the most; he did not sell them to former Senator Nikki Coseteng in the late 1980s when the latter purchased his collection of indigenous textiles. However, Go would eventually sell these to Angel Lontok Cruz, who would bring them to Amsterdam.

These two tapestries, along with many of Go’s collection of textiles, were published in the monograph Sinaunang Habi, written by independent curator and museologist Marian Pastor-Roces and published by the former senator. Of the Miag-ao tapestries at hand, Pastor-Roces writes: “These two pieces are of singular importance. Because of the questions they pose, and the possibilities of further study and scholarship that they open, these textiles are clearly treasures of national importance.” She also notes that these textiles “are therefore extremely rare weaving, which deserves the concentrated attention of scholars.”

The Magnificent September Auction is happening on September 9, 2023, 2 PM, at Eurovilla 1, Rufino corner Legazpi Streets, Legazpi Village, Makati City.