Lawrence De Leon

CAZA Architects principal Carlos Arnaiz in conversation with Julia Nebrija.

The design process begins with a question, not with an architectural style. For instance: how do you reinvent the first contemporary art museum in the Philippines? It’s a question that leads to a complete reimagining of The M, which has been housed in a brutalist structure for 45 years. Inspired by the archipelago itself, the new Met is a light-filled space that is not closed off from but rather engages with its urban surroundings in BGC.

The firm behind this and several other projects across the Philippines, Peru, Colombia, and the USA is CAZA Architects, a design studio and think tank led by Carlos Arnaiz, a Filipino-Colombian architect based in Brooklyn. Adopting a multi-disciplinary, bottom-up approach to design, CAZA has conceptualized buildings and residences that are as innovative as they are rooted in place and heritage.

Aside from the Met, the firm designed the new capitol building of Camarines Sur, masterplanned the Lio Tourism Estate in El Nido, and conceptualized the luxury residences The Wave in Siargao.

For Vogue Philippines Arnaiz speaks to Julia Nebrija, an urban strategist and cycling advocate who launched the Philippine Department of Budget Management’s Green, Green, Green program before moving to Spain. During the pandemic, she co-founded Agile City Partners, a consultancy firm that seeks to advance informal transportation.

JULIA NEBRIJA: I thought an interesting place to start might be an introduction to your process, to hear a little bit more about what it takes to get to “the question.” When we see your list of projects on the website, everything starts with a question. Walk me through your process to getting to those big guiding questions.

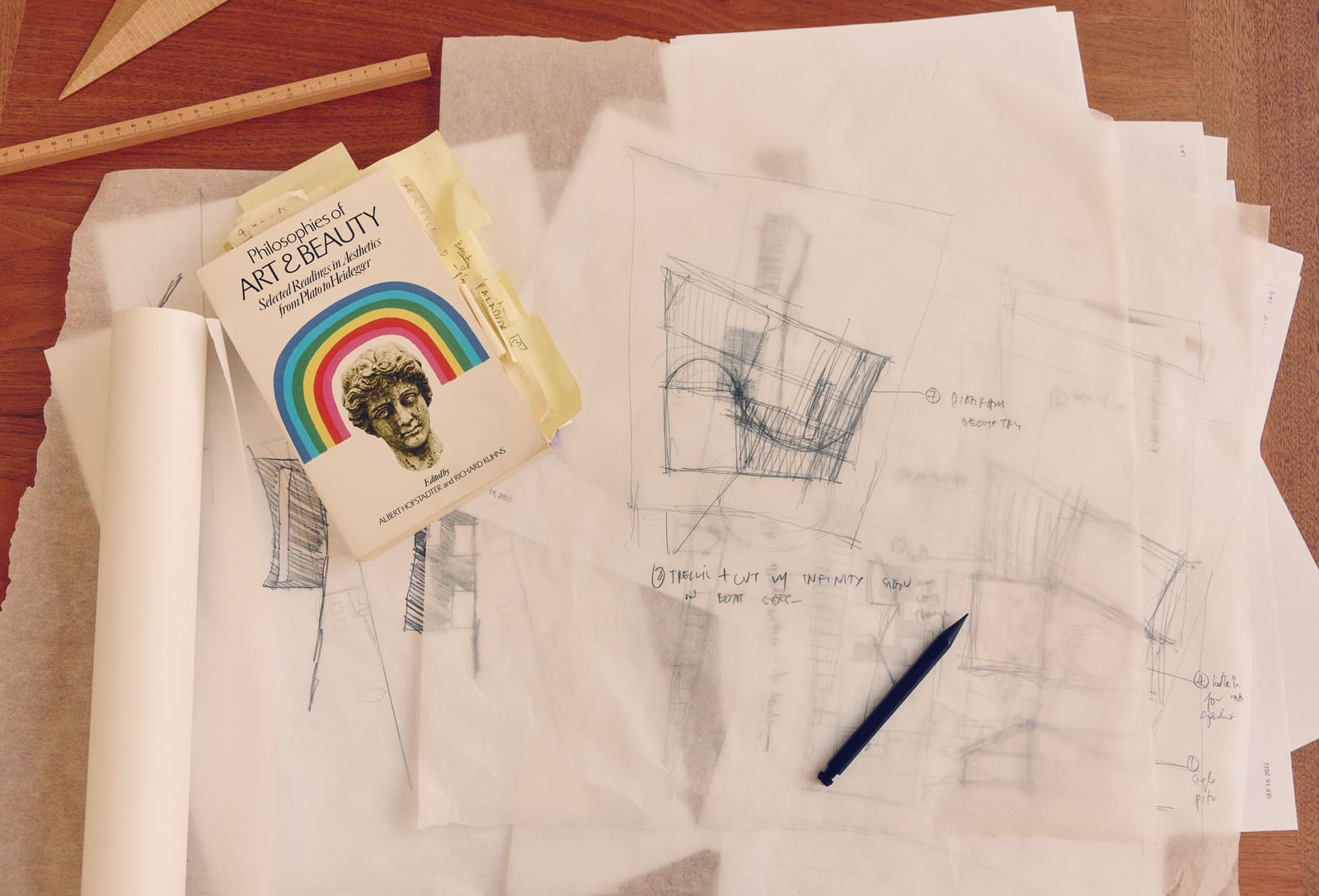

CARLOS ARNAIZ: I actually did not really study architecture initially. I studied philosophy and I think this has very much shaped my approach to design, to planning, and to our environment. Philosophy as a discipline is really one that is grounded on questioning. One of the most basic techniques comes from the Socratic dialogue, which is about just asking the important and sometimes pressing and maybe even stupid questions that need to be asked. I see our role in engaging with the client initially, is to ask, ask, ask, and then listen, listen, listen. And from that to begin to process the questions we must arrive at, you do eventually want to frame the right question. That maybe is the most delicate and important part.

And maybe that’s my big contribution in the studio. I tell my colleagues and the other designers, “don’t think of me as the genius in the room.” I’m not going to come up with the big idea. I rely on you guys to be inspired. My role is to ask the question and to guide you all. That’s how we’re organizing the studio and why we welcome young people. I really love to get fresh ideas, and always try to empower the young designers to come up with their guiding vision. And my role is sort of this Socratic one of using the questions, like a sheep herding tool.

JN: Is that why you’ve made a distinction between your studio work and your think tank work? Do you get to have more of that experimentation on the think tank side, or do they really feed each other?

CA: I like to imagine that they feed each other. Sometimes there has to be a little bit of a space between each one in order to protect some of the incubation of ideas in one, versus the sort of real-world pressing deadlines and professional duties that you have in the other one to clients and budgets and that sort of thing. But there’s a lot of feedback. Maybe this is because I’m not an architect originally—of course now I’m an architect—but I have a little pet peeve with the typical, what I call the “mythology” of the architect, which is this notion that the architect is this genius character who comes up with this brilliant, inspired idea. And then the world ruins it. Either the budget is too small or the client decides to make it economically feasible or whatever, all of these things. And then the architect is frustrated, this is the myth of the architect in my opinion.

I tell this to my students, that’s honestly BS. Our role is to work with people, and so many good ideas come from other places we don’t understand, from politicians who have their own constituents they need to address, from clients who are trying to figure out how to make a business model work from all of these different things. I think as an architect, you must be a team player. It’s like saying, how do you play soccer by yourself? You’re playing with other 10 players. This goes back to your question about the think tank, some of the best ideas or nuggets, seeds of ideas that, and experimental concepts have come from places that we didn’t expect.

I really believe in collaboration, and I think an architect needs to be this very agile social being, willing to engage in this act of building community through space, but that’s not just building community physically through the things we build, but also through the conversations we have and through open dialogue. I think that’s a very important part of our discipline.

JN: So as a kind of conductor of this orchestra with all of its moving parts, and you mentioned that you got there through philosophy, but what do you think about your background, your multicultural upbringing, or the way that you grew up? Or how you have studios all over the world and you’re based in New York, how does that feed into your ability to play that role and be able to guide those conversations?

CA: That’s a wonderful question. I’ve only now in my later years—I sound like an old person—but I think 20 or 15 years ago when I started, I probably didn’t understand this that well, but now I’m beginning to realize much more that my multicultural background, what I sometimes call my exiled personality, that I’m neither here nor there exactly in the sense that I’m kind of not home anywhere, but I’m always looking for home. I’m really interested in the idea of communities trying to build home, while at the same time realizing that we’re always slightly displaced. That’s just the nature of our global environment, whether it’s because of politics, war, climate change, there’s so many sort of unsettling systems in our surroundings that we’re working against this trying to be positive.

And I think my upbringing, which by the way, is not unique to me anymore. I think this is now a much more shared experience. It’s becoming this sort of global nomadic sense that we’re kind of shifting, we’re in many places at the same time. It’s a huge frame of reference for how I operate. It’s always in the background and it’s very much influenced how I approach architecture, maybe even why I did architecture to some degree. When I was doing philosophy, I was very interested in questions of colonial identity. I was very interested in writers, for example, who tried to build communities through their novels. I was very interested in questions of exile, existential philosophy. So these were things that 25 years ago, I was really embedded in.

JN: I think that whether or not you’re a global nomad, the idea of having everything, building your home in one place is just so difficult to attain at this point in time. It’s constantly evolving and possibly also helping to see things that you don’t normally see if you’ve only been in this one place for so long. I think that was something that I felt in the Philippines, kind of being like that insider outsider, like I belong because of heritage, but I’m not from there. I could kind of see things a little bit differently sometimes, maybe.

CA: Absolutely. I’m going to say something that’s maybe a little controversial, but I do believe that architecture has a political role to play and that political role is very subtle. If you look at its history architecture has been wielded as a tool for power, since the Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians, right? It’s always been utilized by those in power to establish certain visual and social protocols, but today, where there are so many possible truths and also many emerging identities, and there’s a lot of contested issues about who’s at home and where we are at home. I think the idea of making architecture that’s in dialogue, that is open to questions, that’s saying, yes, we can build a place, but we’re also cognizant of the boundaries of those places. And the fact that they can be sometimes vague and we should also be welcome to outsiders.

I think those are all important political messages. There’s the reality of a global nomadic culture emerging. There’s also, on the other hand, a very strong will to be exclusionary and you see it everywhere now in all parts of the world. That’s real and it’s also kind of unsettling. And I think it’s a struggle to work through those. Those are emotions about fear and loss. And in a way, architecture is an emotional discipline. It deals with the production of effects, because good architecture produces emotional effects. As professionals in this space, we can wield that power for the benefit of our communities to produce the effects that maybe bring us together as opposed to separate us, you know?

JN: And where does the Philippines fall into all of this for you? What continues to draw you back to do projects that are quite difficult sometimes to do in the Philippines? What do you think draws you there, inspires you, excites you, or why keep coming back to invest in the Philippines for architecture and urban design?

CA: The Philippines is so fascinating. I don’t have to tell you this because you’re as much from there as I am, but it’s such a bizarre country in the sense that it’s very much of a chameleon, it’s constantly changing. All of these qualities I love. It’s an archipelago, in the sense that it’s this splattering of islands in the middle of these oceans, so therefore it’s never been clearly bounded. It has such a mix of cultures that it’s constantly shape shifting.

The fact that it’s also a site of extreme climate change, it’s one of the countries that’s most exposed to typhoons, to earthquakes, which makes architecture even much more stringent and prescient in the way in which you need to produce it and handle its questions of resilience and robustness. I often say that the two most pressing issues for architecture today is, on one hand the environment. The way in which we conceive of nature today is not what nature was 50 or a hundred years ago. This is nature that is deeply affected by human intervention. There’s almost no pure nature anymore. We therefore really need to understand how we enter into those metabolic processes that create the environment, and architecture is embedded in that.

And the second thing is the digital network systems that we’ve created for communication that has completely changed the way we engage with ourselves in communities. Architecture is part of that medium of communication. I think those two paradigms in the Philippines are also super elevated in the sense that people are highly linked. In a way it’s also a nomadic country with such a wide diaspora of people dispersed around the world. You find Filipinos living everywhere. And then all of these young Filipinos who are quite innovative and tech savvy, but also in a place where the environment is really also quite damaged to some degree. All of those problems I find super enthralling and challenging. I don’t mean problems in the negative way. In philosophy, problems are actually positive things to return to, they’re like questions to some degree.

JN: So where do you see the biggest opportunities in the Philippines then? What are you excited about next?

CA: I think beginning with the pandemic, one of the fascinating things that resulted in the pandemic is our heightened awareness of the importance of health. The Philippines already has an amazing human health infrastructure with very talented doctors and nurses who are well educated. Oftentimes they are the ones who service hospitals around the world. Part of the question is how to establish a health infrastructure in the Philippines that truly aids the communities at a more rural scale. We actually designed a series of prototypes. Some of them are being built, small scale hospitals outside the big cities that are geared toward more intimate relationships with the towns and the communities.

The second is that I feel like there’s lots of room for agricultural innovation in the Philippines. People who are much smarter than me in this space have talked about the need for a real food revolution in the Philippines. The way in which architecture can play a role there is to augment education, the by-product between education, innovation and agriculture, and how you create spaces, whether they’re labs or schools or agri communities. We’ve master planned a few towns that are built around organic farming and teaching communities how to do more sustainable farming and how to also make it part of a kind of slow food movement, so there’s also a tourism element to it.

The last thing I’m most excited about is, as all of these new projects are getting built, whether they’re their hotels, resorts, schools, or churches, I’m constantly searching for the language of this emerging country. Of course, the Philippines is not young, but I think our identity is still being formed. And part of what’s really interesting about the Philippines is that it’s not a country that’s afraid to say we are in formation. Other countries, especially in Asia that have these long, deep histories; they would say they know exactly who they are. I think the Filipinos, in a sense, are lucky to say that, Hey, we are still in formation. And I think architecture plays a role in that.

This article was originally published in Vogue Philippines’ November 2022 issue. Subscribe here.

Photography by Lawrence De Leon.