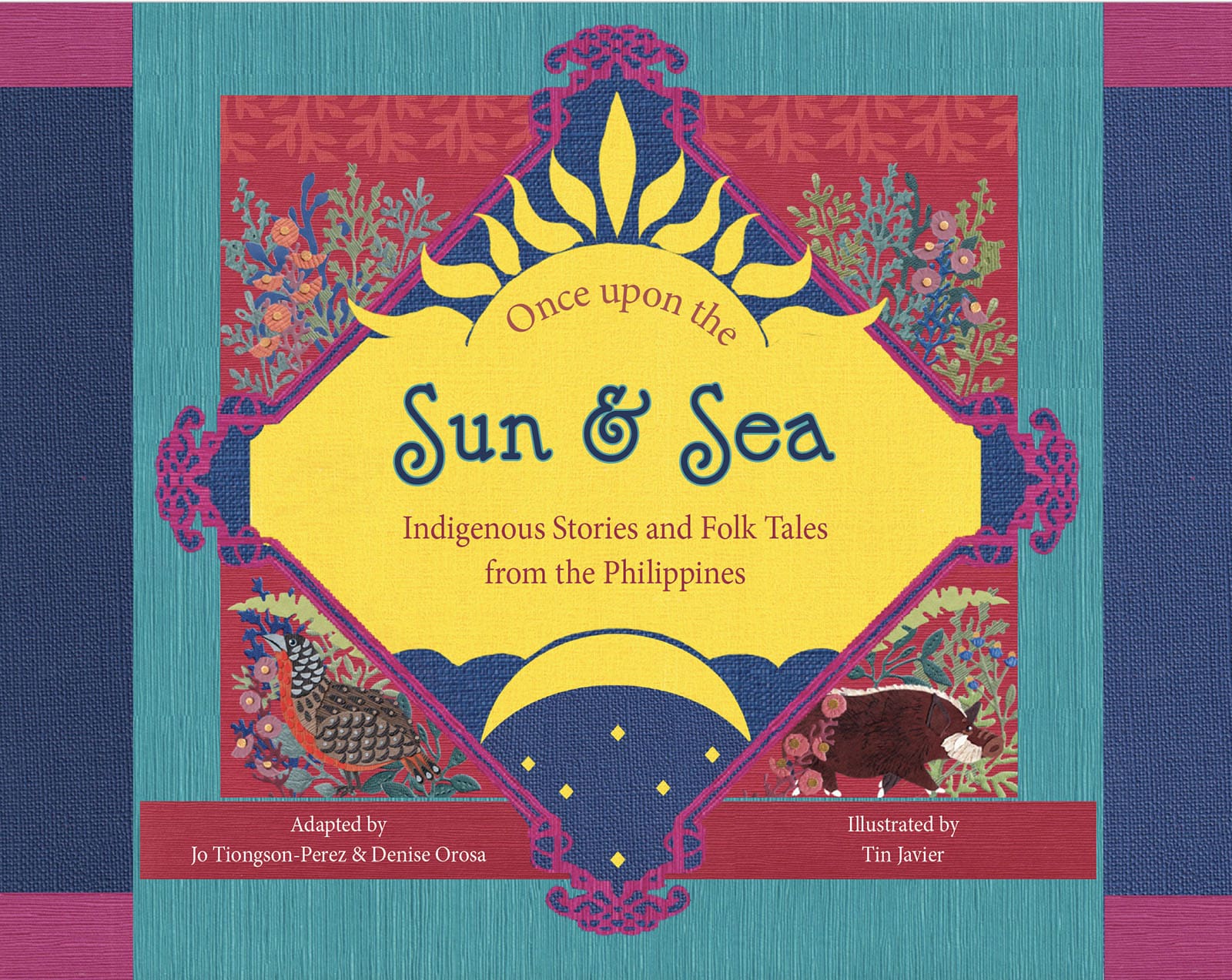

Illustration by Tin Javier. Photos courtesy of Joanne Tiongson-Perez and Denise Orosa

When a child asks you to tell a bedtime story, does your mind immediately reach for a Hans Christian Andersen or Brothers Grimm fairy tale, a Disney revisionist princess drama, maybe even a Greek myth? For writers and mothers Joanne Tiongson-Perez and Denise Orosa, Filipinos who live in Philadelphia and Canada respectively, they wondered why the stories they tell are hardly ever Filipino ones. When their own children began asking for stories from the Philippines, wanting to learn more about their heritage, they realized there was an opportunity to present Indigenous Filipino literature to children of the diaspora.

Their illustrated children’s book, Once Upon the Sun and Sea: Indigenous Stories and Folk Tales from the Philippines, “was the culmination of conversations we’ve been having as moms raising our kids outside of the Philippines,” says Tiongson-Perez, who is currently the marketing and communications chief of Penn Museum. In 2021, she and her former UA&P classmate Orosa applied for a grant given by the Sachs Program for Arts Innovation that supported AAPI artists during a time of increased racism against Asian Americans. As they got deep into their research, they were surprised to discover that these Indigenous tales had been characterized as “inferior, savage, primitive, less than,” Tiongosn-Perez says. “So that could have also contributed to the fact that they never became part of the canon of popular storytelling within our country.”

“We really wanted to try to make space for these indigenous narratives. Because the stories are out there, but they don’t come easily to us when our children ask us to tell a story. They’re not embedded in that way,” says Orosa, an award-winning arts and elementary educator currently living in Ontario. They worked with the non-profit group Byanyas Foundation, who connected them with elders from the Tagbanua community in Palawan and helped obtain consent to use their stories. The Tagbanua elders made recordings for Tiongson-Perez and Orosa, who then translated the text to English.

“That process encouraged us just to listen to what the community wanted,” says Tiongson-Perez. The elders were specific about not publishing the recordings anywhere. “In honoring what they wanted, and even in the process of translating, we had to be very sensitive about the translation. We needed to make sure that we were not prescribing modern frameworks of storytelling archetypes that sometimes are very Westernized.”

For this, they consulted Andrea M. Ragragio, an anthropologist from the University of the Philippines who has worked with the Pantaron Manobo of Southern Mindanao for decades. Ragragio informed them that when these types of stories get interpreted, modern frameworks are often applied, and the essence of the story gets lost. They learned, for instance, that in that specific Manobo community, “there are no binary values like good and evil, there’s just a continuum of existence.”

Many of the indigenous stories they encountered were challenging in the sense that they didn’t conform to the usual fairy tale narrative arcs we are familiar with. “We were trying to stay as true to the story as possible without asking where’s the introduction? Where’s the conflict? Where’s the resolution?” Tiongson-Perez says. “It’s meant to be this moment in time where the characters are inseparable from the environment, and they’re just moving through that space.”

Of the eleven tales in the book, two are from the Tagbanua, and the others are adaptations of stories from different regions of the Philippines. The authors noticed that the indigenous tales from the highlands were distinct from those from the Christianized lowlands, whose folk tales reflected a clear moral value system. The Tagalog epic Ibong Adarna, one of the most well-known and loved of Filipino stories, also contains recognizable themes and archetypes, like the princess in need of rescuing.

The collection of stories in the book reflects the diversity of storytelling. One version of the story of Aponibolinayen and the Sun from the Itneg group in Abra delightfully provides a female character who literally refuses to dim her own light for her partner, Init-Init or the Sun. While the story bears striking similarity to Jack and the Beanstalk, with a vine carrying the radiant girl Aponibolinayen up to the sky realms, the tale also reveals the dynamic between a married couple, with a husband who is insecure about his wife’s own power (although they live happily ever after—once he “accepted her truth.”)

Illustrating the stories is Tin Javier, a collage and mixed media artist from Cavite who used a pattern and texture-rich punched paper technique. Known for her folklore-inspired art and advocacies for indigenous peoples, Javier was a perfect fit for this project. “She applied so much academic rigor to researching and put so much thought into all of the choices that she made,” Orosa say. “She really brought the stories to life.”

Ultimately, the authors hope the book inspires curiosity and pride in the children of the diaspora and beyond as they seek out connections to the homelands and discover the rich oral literature of the Filipino people. “The stories are every bit as magical and powerful and beautiful [as Western narratives],” says Orosa. “We feel that there’s space for all of those—so let’s make space for all of them.”