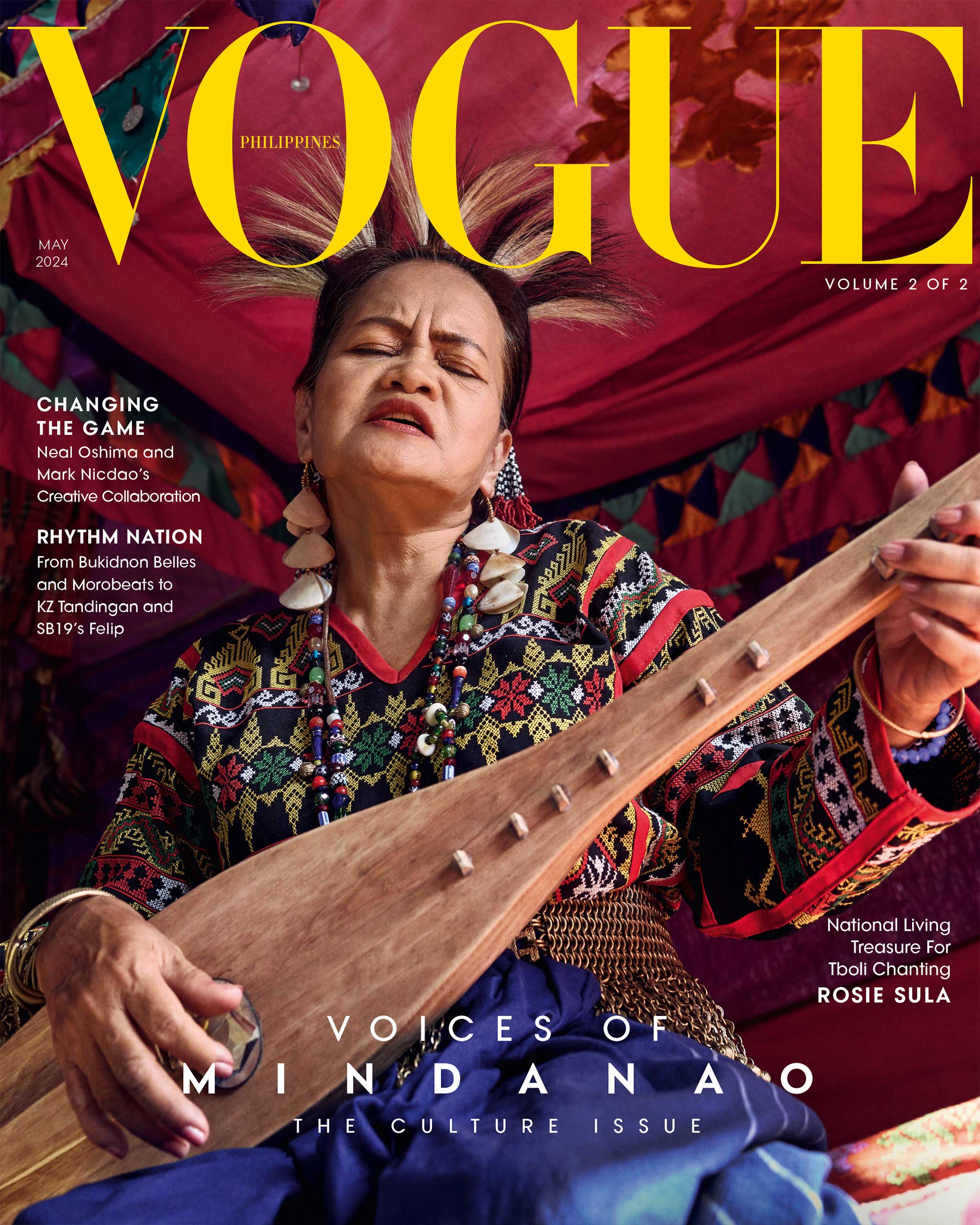

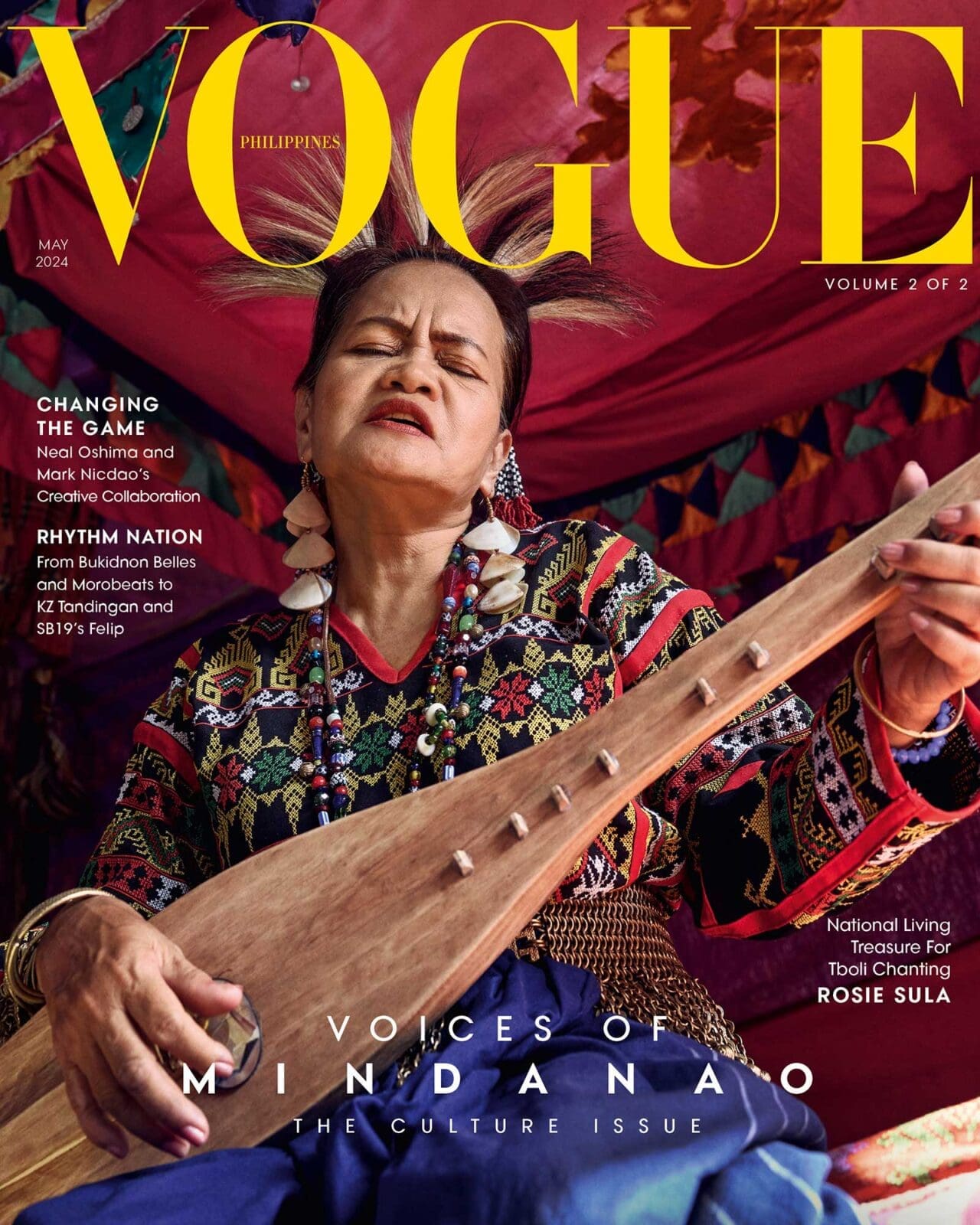

“I have no time for my husband, children, or myself—everything I do is for the nation,” says the youngest GAMABA awardee.

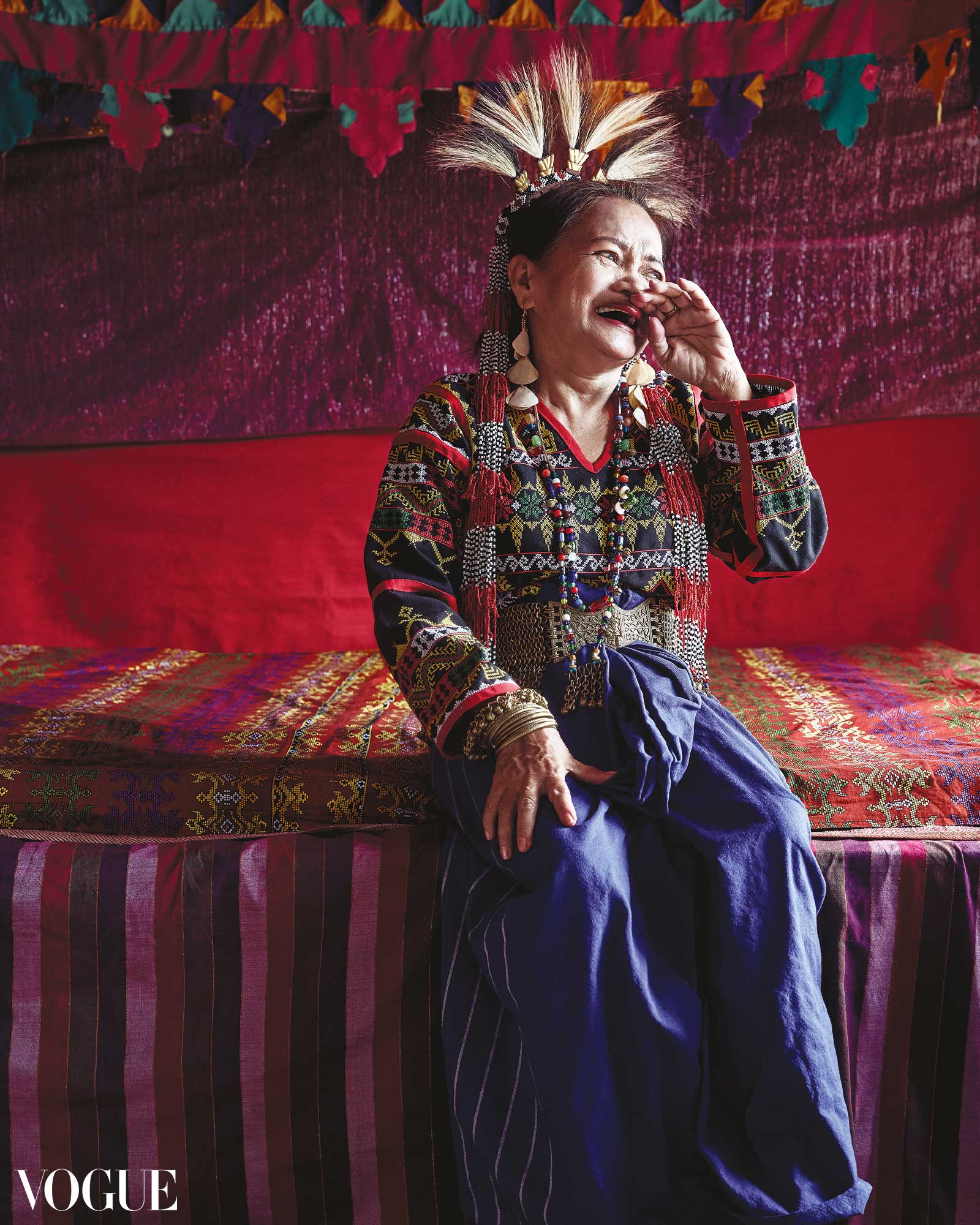

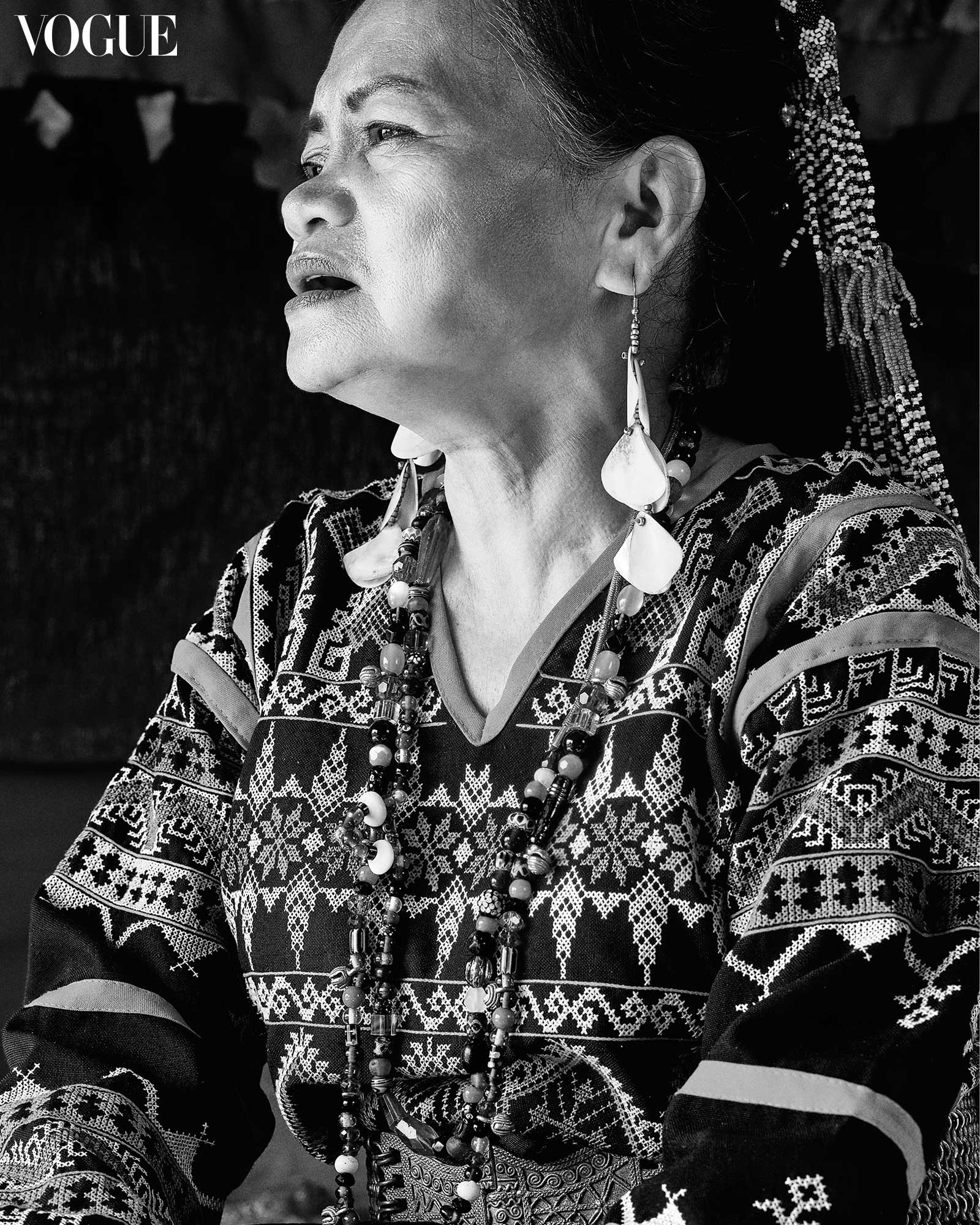

The chanting, as all Tboli chants do, begins with a powerful and startling “HEDEEE EHE EEEE.” It is a call that summons the singer’s spirit guide, the helper who will lead her into song. The spirit guide is the song, and without it the singer would be at a loss for words, unable to find a tune. The spirit guide’s music must be followed.

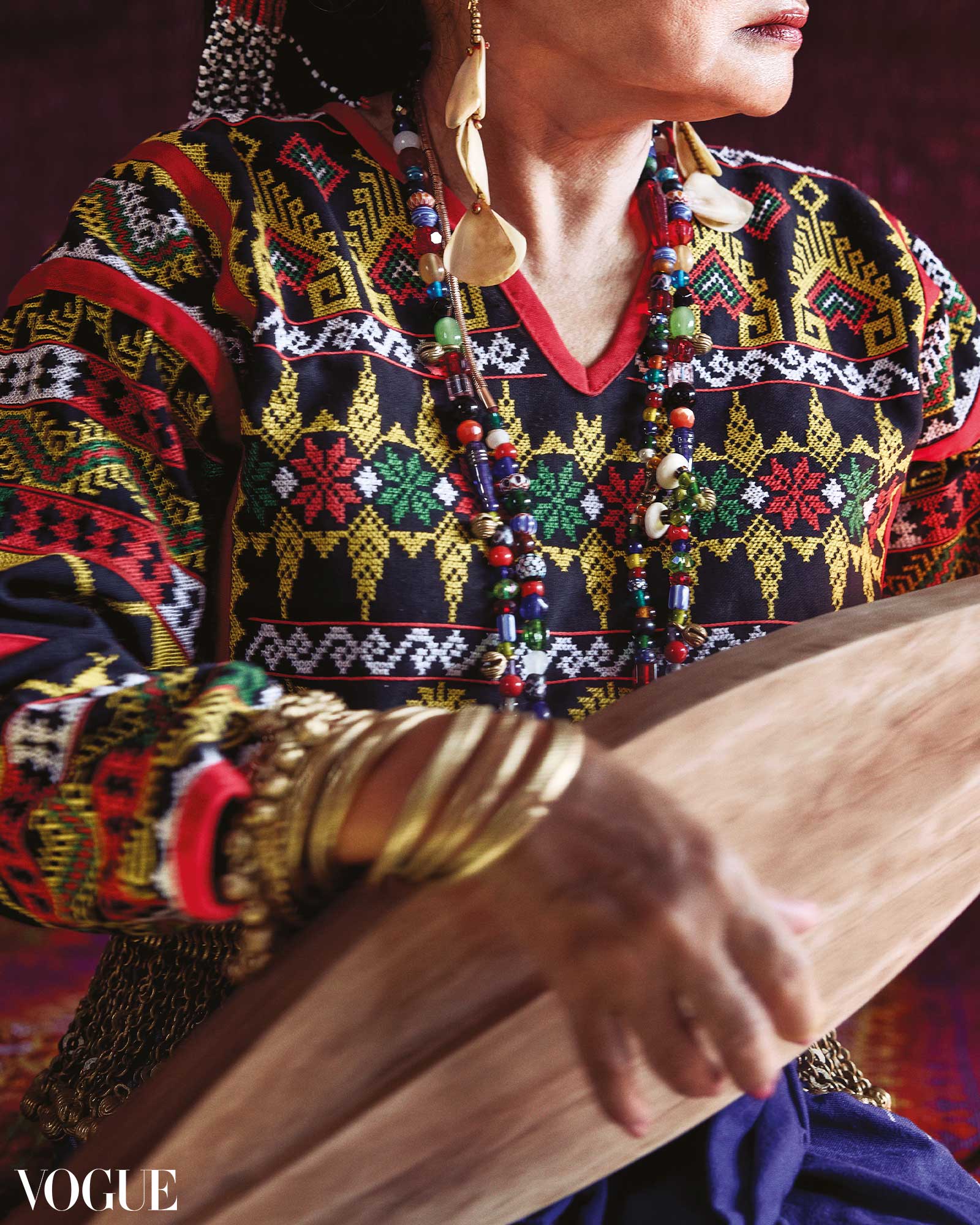

For Rosie Godwino Sula, the Tboli artist from Lake Sebu, South Cotabato who was in December 2023 named a National Living Treasure for chanting, it is the Holy Spirit who heeds her call. “The Holy Spirit dictates to my mind, my mouth, and my heart so the perfect words come out,” she says.

You may have already heard her singing—hers is the voice that introduces the Mindanao chapter of Catriona Gray’s “This is the Philippines” series on YouTube. In the video, Catriona plucks a pink water lily from the water as she is rowed around the lake in a dugout canoe. The notes of Sula’s chant glides along with the ripples of the lake. According to Sula, her song was a prayer for her to win the Miss Universe 2018 competition.

Without the gift of the spirit—whether it is Lentinum, Tboli spirit of the skies, or the Holy Spirit itself—“you won’t be able to compose an epic,” Sula says. There is only one epic when talking about Tboli epic chanting, and that is the legend of the hero Tudbulul, whose life is recounted in eight long episodes. Chanting the full epic, which spans Tudbulul’s birth to his death and the many adventures in between, can take over three nights and is usually performed at important ceremonial events. The story of Tudbulul is central to the identity of the Tboli, who over generations have absorbed the values and ethics that the tale imparts. As ethnomusicologist Manotele Mora outlines in his writings on Tboli music, each episode of the epic is coded with an aspect of the customary laws of Tboli society.

Sula comes from a distinguished Tboli family of musicians and community leaders in Lake Sebu. She learned the musical arts from her father, becoming proficient with the klintang (gongs), the hegelung (two-stringed lute) and all the other instruments, but it was chanting where she showed exceptional talent, and at the age of seven she was already performing short community and folk songs.

Tboli chanting is an oral tradition and the chants are not written down, they have no fixed lyrics. A chanter recreates the song every time it is performed; its words are often improvised.

Thus the lengthy Tudbulul epic can only be taken on by those who have reached a level of adeptness. Sula’s first composition was about the marriage of Tudbulul. “For the first time in the history of chanters, there has never been a Tudbulul who was a peacemaker,” she says. “I wanted to create a Tudbulul who was a peacemaker.”

A traditional culture bearer who has traveled the world performing Tboli music and dance for different institutions, Sula considers herself foremost a cultural activist. “When I was nominated [for the Gawad ng Manlilikha ng Bayan], the biography written about me was just a glimpse of who I am. Becoming a Manlilikha ng Bayan, I had to pass through the eye of a needle,” she said in Filipino at a workshop given at the University of the Philippines. Aside from being an educator, a public servant working for the NCIP, and founder of her own school of living traditions called Gono Lemingon (House of Chanting), Rosie has also acted as a mediator and a peacemaker for the community. She is known as Boi Lemingon, a title referring to her respected status as a chanter. On Saturdays, she teaches children how to sing folk songs; on Sundays, she teaches the Word of God. “I have no time for my husband, children, or myself—everything I do is for the nation.”

Several years ago she formed Libun Hulung Matul, a women empowerment group consisting of skilled artisans who are also the breadwinners in their families. Sula strongly advocates for changing some of the ingrained beliefs of her society that oppress women, particularly the practice of polygamy. She discusses the generational heartache she has inherited from the women in her family: Her father had eight wives, while her grandfather had 36 wives, by far the most of any Tboli male that she can remember. When Sula’s mother, who was her father’s first wife, died from a heart condition, she blamed it on her father’s many marriages. Her father countered this by saying that as a chanter, it was necessary for Rosie to experience what she did because it is what the epic of Tudbulul is all about. To become an adept, her father seemed to be saying, she had to embody the chant, not just its music, but its meaning.

Tudbulul, of course, had multiple wives. The tale also tells of arranged marriages and child-brides who were exchanged for gongs and horses. It has episodes where he is shown mistreating women and not working hard to provide for his wives. In Babaylan Sing Back, Grace Nono’s scholarly work on indigenous ritual specialists, she explores how the Tudbulul epic has served to reinforce patriarchal gendered relations. However, she notes that because the text of the epic is not bounded, both singers and listeners can reinterpret and subvert its messages to suit their needs: “The Tudbulul that had been accused of being responsible for much of the Tboli women’s suffering, has been…turned into a force for inciting Tboli ken libun [women] to rise up and change their condition of subjugation.”

Rosie’s Tudbulul is a peacemaker, and it wouldn’t be surprising if she also composed him as a loving husband to only one wife. “My one request as a Manlilikha ng Bayan is that the government listens to us indigenous people, especially the women,” she says. “The VAWC [Violence Against Women and Children] laws do not seem to apply to the IP. For us IP women, I wish for the duwaya [polygamous marriage] system to be abolished.” Sula is working on a book called Justice System for Tboli Women, although, she says, her draft has not been approved by the datu, the male elders and leaders of the community.

As the youngest GAMABA awardee at 55 years old, Sula still has many years to see the rest of her dreams for the Tboli women come true. She will dance, and she will fight, wherever she is called to. “And with the Holy Spirit leading me,” she says, “I will never stop singing.”