Photography by Jason Ta

Photography by Jason Tan

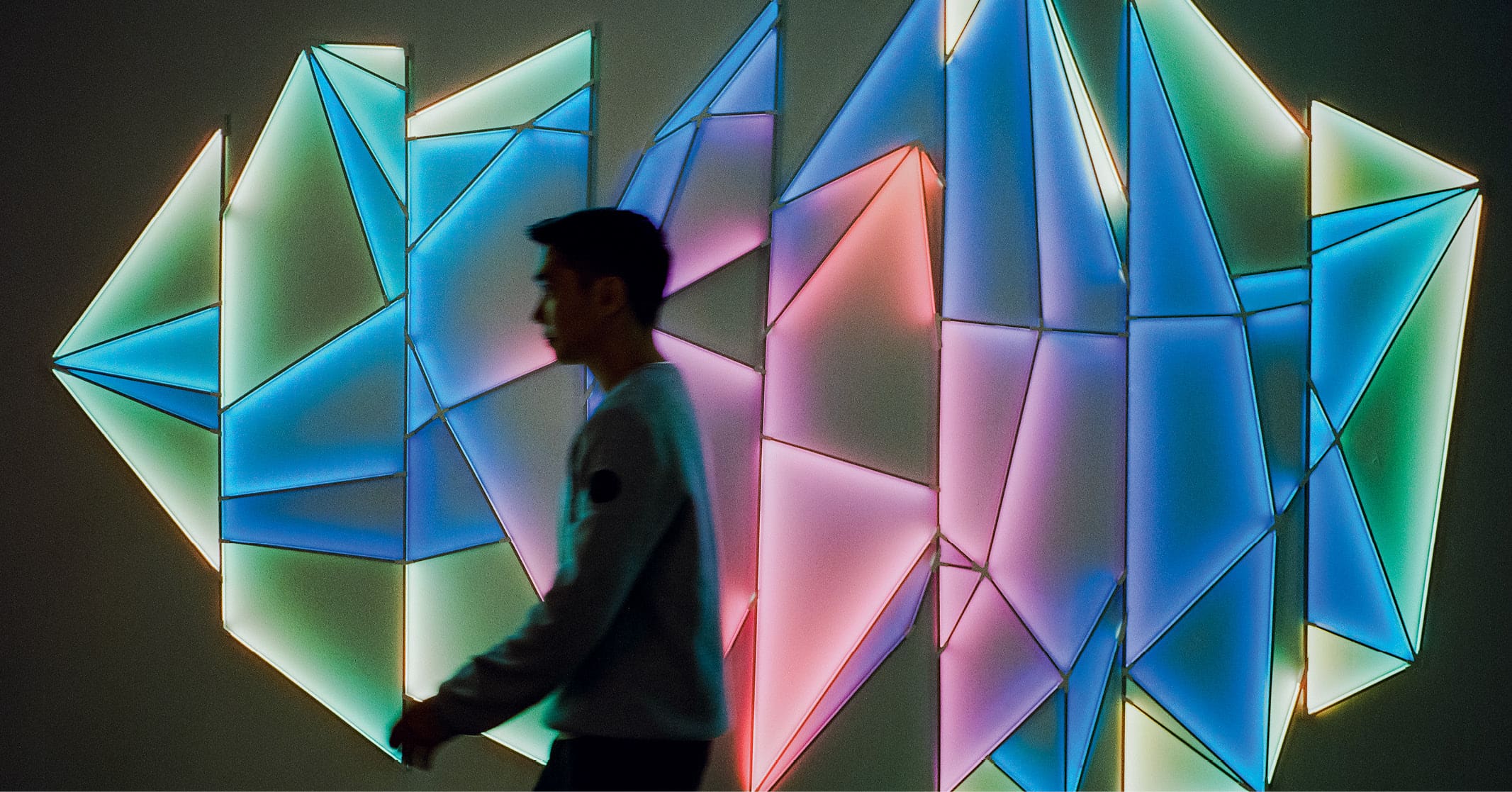

James Clar uses light and technology to reveal the underlying tensions of modern life. His latest work—after moving to the Philippines—shows the artist in a new light.

Among the siblings that make up the slightly dysfunctional, often misunderstood family of Filipino core values, hiya is one that has had a lasting hold on the molding of Filipino psyches, especially women. Traditionally, Filipino women are taught to be modest, agreeable, to not question authority, and to not have the last serving (the hiya piece), for fear of being embarrassed or bringing dishonor to one’s family.

Walang hiya, then, has been used as an expression to shame those who do not exhibit these traits, someone who flaunts commonly held notions of propriety. Walang Hiya is also the title of artist James Clar’s exhibition at Silverlens Galleries NYC, the gallery’s first solo show since it opened last September, and Clar’s first show back in the city he called home for 15 years.

Ahead of the New York opening in March, Clar guides me through a virtual tour of the gallery space on his computer. We enter, greeted by a light fixture in the shape of a light fixture—that is, an LED light installation depicting one of those retro-looking spotlights used in CCP. Clar explains that it was borne from a fascination with the idea of how much this light fixture has seen and allowed to be seen. This framework of a light switch, which can be controlled to illuminate or to hide, sets up the rest of the show.

There is a chainsaw in a mirrorbox, replicated to infinity. It is one of the many chainsaws confiscated in Palawan from illegal loggers who have been brazenly denuding the Philippines’ so-called last frontier. Walang hiya talaga. Along the hallway, video screens project interviews Clar conducted with parents of other Filipino artists. He asked them questions like what they thought of their art. Clar’s own parents were also interviewed. “They still don’t understand what I do, or why I moved back to the Philippines,” he laughs. Despite this, they are proud of him. Wala silang hiya.

We move to an unusual collaboration with Olympic weightlifter Hidilyn Diaz. “I became really interested in working with her and in what she represents here,” he says. Diaz made history as the first Filipino Olympic gold medalist, but what’s truly inspiring is how she came from a very humble background and, in both senses of the word, built herself up. Clar tracked Diaz down, but it took a while for her to come around to the project since it had nothing to do with sports. When she finally agreed, Clar drove out to Jala Jala, Rizal, where she and her husband Julius Naranjo live and where they started the HD Weightlifting Academy in their backyard.

Clar recorded Diaz’ brainwaves during three states: while she was sleeping, working out, and watching the playback of an indelible memory, her historic win at the Tokyo Olympics. “When we’re sleeping, we’re all the same. We’re in this physical resting state, but the mind is dreaming about things. And when you’re awake, that’s when you change,’ he says. “The exhibit is about our potential, not just in sports but in arts and culture. It’s great to have these kinds of figures to kind of show the potential of what we can do.”

The brainwave data will be used to design the light structures that will illuminate other parts of the installation, which include the actual weight plates Diaz used in Tokyo, and pieces of sheet metal indented with the full force of a 280-pound barbell thrown down on it. One could see it as the weight of shame being cast off; Diaz has been candid about how she was bullied as a young girl and athlete, how she started to hide herself and her body because she was “big.”

Clar is also exploring the complicated relationship he has with his own identity, something he decided to embrace by moving to the Philippines in 2021. He grew up in a small town in Wisconsin, where there were no other people who looked like him. The dearth of any kind of creative stimuli forced him to rely on his own imagination, however, and this set him off on the path of an artist.

He went to NYU for film and got a master’s degree in interactive telecommunications, a program that explores the creative use of technology, switching over from strictly film-based work into structural lighting, experimental lighting and video installation. “I realized that maybe I don’t have to use [the film] format,” he says. “I can start creating my own format or my own kind of styles or systems for communicating emotions.” Experimenting with how light creates depth, how color shades emotions, how screens mediate events, how sound evokes environments, even developing his own patent for an electrical system, Clar continued to push different possibilities, different potentials and ways of being. He has since made over 300 individual artworks that reflect, in both senses of the word, his observations and experiences from living for two years in Tokyo, six in Dubai, and back to New York for another eight years.

“The way I approach the art is like they’re like breadcrumbs of where you are, what you’re thinking about, who you’re talking to, and the ideas and the situations and the emotions that you’re feeling at that time,”

he says. “It becomes a continuous story.”

The story pivoted, like most things did, during the pandemic, which triggered something he had been contemplating for a while. In the US, he felt like he couldn’t really call himself a Filipino artist, even though his parents are from the Philippines. The only way he could do so was to relocate his studio to Manila. “I needed to understand what it is like to be in the Philippines, and to understand my parents’ culture, and just really immerse myself and become part of the art scene here,” he says. “If I wanted to include that into my storyline, into the works that I do, I had to move.”

Rachel Rillo, co-director of Silverlens Galleries, thinks that his move to the Philippines is brave and exciting. “From my experience, having moved back to the Philippines from the US, it takes about two to three years before you hit a wall… when all you used to know from the place you left is distant and the place you’re at is a little too real, too close,” she says. “When the romance and promise of ‘identity’ and ‘home’ is more abstract and daily life takes over. So I think this coming show will be that discourse. He is wearing different lenses now that he lives in the Philippines, and it will be exciting to see the new work, and interesting to see if New York will see him clearer.”

On the main wall of the exhibition space in New York will hang two light sculptures in the shape of a parol—one, a singular star, the other, its mesmerizing, kaleidoscopic twin. Clar says they represent the individual and the community. He has been home for close to two years, and he did spend a very Filipino Christmas in Jalo Jalo with Hidilyn, Julius, and the kids in the community who take part in their training camps. Like the prismatic parol reverberating with color, encompassing the individual, daily life is taking over.