“Vintage style, not vintage values.”

Vintage clothing is inescapable at the moment. Red carpets and Instagram feeds are filled with archival Versace (worn in the last year by Jenna Ortega, Bella Hadid, and Zendaya), Jean Paul Gaultier (Hadid, the entire Kardashian-Jenner clan, Olivia Rodrigo), and Valentino (Vogue’s Five-Minute Fashion Month Debrief: Paris Edition”>Zendaya and Emma Chamberlain). Rose-tinted nostalgia has also been an undercurrent of many runway collections this season, from the wasp waists at Dior to the power shoulders at Saint Laurent. It’s easy to love clothes from long ago—but for some people, the appeal goes far deeper. There are those who wear gowns modeled after the mistresses of Versailles, or 1860s silhouettes remixed in modern fabrics. Hobbyists who painstakingly reconstruct robes à la française for hundreds of hours, or dedicated historians for whom wearing a century (or centuries)-old style is an extension of their careers. Whether they call themselves historical costumers, interpreters, or vintage enthusiasts, their dedication to the aesthetics of the past is compelling. If fashion is a form of self-expression, what does it mean to forgo modern trends in favor of 18th-, 19th-, or 20th-century silhouettes?

It’s a pressing question for people of color who have embraced antique or historical clothing. A common refrain is “vintage style, not vintage values”; in other words, “we may dress this way, but please don’t assume we want to actually revert back to the 1950s or the 1860s.” So says Christine Millar, M.D., an anesthesiologist and historical costumer who favors 18th-century European gowns adorned with ruffles. “I do think it’s important to put ourselves out there, because there aren’t that many minorities in historical costuming. Those of us saying ‘vintage style, not vintage values’ are also saying that there were people of color in the past, and they [also] wear these fashions.”

For some, anachronistic attire is a conversation-starter; for others, it’s merely a joyful form of escapism. Either way, it can offer the rest of us a captivating lesson in history, style, and identity. Below, meet seven women and their wardrobes.

Cheyney McKnight

Cheyney McKnight attracts a fair amount of attention as we walk from the lake in Central Park, across the bike path, and into the Upper West Side. McKnight is wearing a dress she designed based on an 1860s pattern with 1830s sleeves, rendered in a modern African wax print. Even under her black puffer coat, the reinforced skirt’s wide circumference is hard for passersby to miss, and stylist Jason Lamar had braided her hair into a chignon also inspired by the 19th century. McKnight refers to her look as a form of Afrofuturism, and a kind of armor that allows her to work as a historical interpreter, YouTuber, and influencer. “The work I do is very taxing and difficult,” McKnight says. Her custom wardrobe “makes me feel strong, powerful, and it makes me feel like I can go toe-to-toe with anyone and everyone.”

Everything I do—everything—is for my ancestors.

McKnight is known online under the handle @notyourmommashistory, which she uses to educate people about the lives of enslaved people (of whom she is a direct descendent). In 2017, she staged a work of performance art in which she walked around Manhattan in historical dress, holding a sign that read “What to a Slave Is the Fourth of July”; and last summer, she set up a roving booth called the Let’s Talk About Slavery table. Her everyday outfits combine her love of 19th-century silhouettes with fabrics common in contemporary Black culture, such as denim and Lycra. “I don’t see this as clothing of the past,” she says. “I see this as clothing of the future.”

In her work as a historical interpreter, juxtaposing anachronistic silhouettes with familiar fabrics also helps McKnight to “jolt people out of the fantasy world a lot of historical sites are trying to build.” She’s found that some plantations use the splendor of the house and landscape to gloss over what life was like for Black people there. “When you walk in, you’re in a beautiful entry hall,” she says. “You never encounter a servant entrance, say, so you don’t have to think about the fact that a plantation is a forced labor camp.” Reinterpreting the clothing that enslaved women would have worn in surprising, modern textiles, she began to feel more empowered and protected in those spaces. “I really felt that it could be the difference between someone touching me or someone deciding not to touch me. And then I realized the first time I wore it, no one touched me,” she says. The strength afforded by the looks translated to modern-day New York City, as well. “If my ancestors could dress however they wanted to, I imagine this is how they wanted to dress,” she says. “Everything I do—everything—is for my ancestors.”

Xiaoye Du & Heather Guo

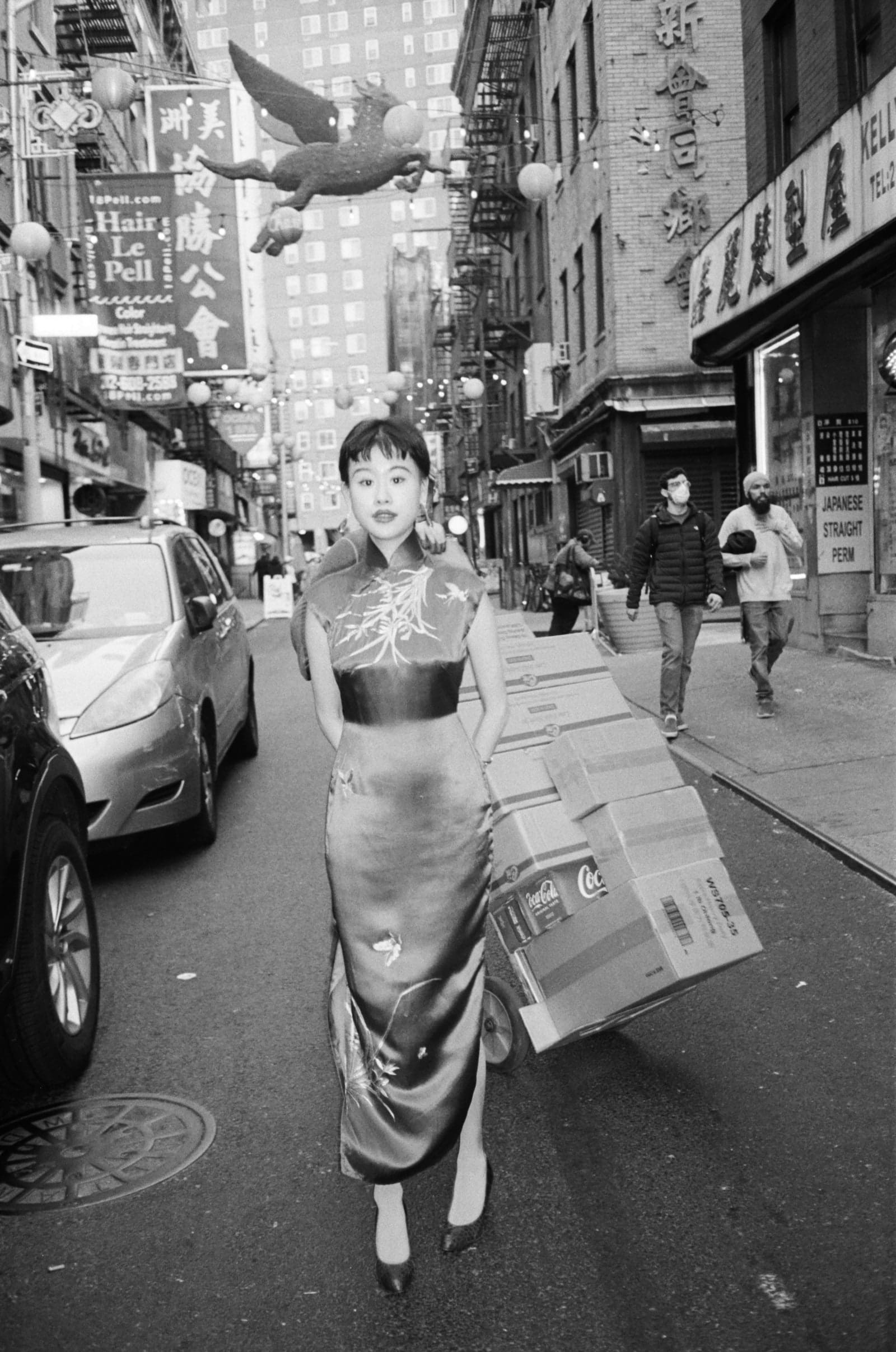

Heather Guo & Xiaoye Du in mid-century vintage qipaos.

Xiaoye Du and Heather Guo met at the Manhattan Vintage Show in 2021. United by a shared interest in “vintage fashion, Chinese fashion history, Chinese opera and literature, and beauty in general,” according to Du, the two became fast friends. Du, a language teacher, and Guo, a student at NYU, started staging photoshoots together in early 2022 to document their similar mid-century aesthetics, which included not only wasp-waisted dresses and delicate hats, but also qipaos and Chinese brocade jackets from the 1920s.

I decided to start wearing qipaos more often, as a kind of statement—like, Look, I’m Chinese, and what are you gonna do about it?

Guo says their everyday looks (a sweater, necklace, and pants from the 1950s, say) go largely unnoticed: “We blend into the city.” Still, there’s a transportative element to what they do. “With vintage clothing, especially my qipaos, I can’t just throw it on and forget that I am wearing it as I go about my day,” Du says. “I constantly feel it on my body, I’m always adjusting it and finessing it. I feel the tension of the tightly fitted stiff high collar. I need to undo the collar when I get into a car or simply to sit down to eat. This interaction with my clothes serves as a constant reminder of what I’m wearing.”

A vintage brocade qipao from Xiaoye’s collection.

Both collect qipaos from the 20th century, and can talk at length about the distinctions between one made in the 1920s versus another from the 1960s. They believe it’s important not only to wear them, but to document them, too (they want to start an Instagram account devoted to Chinese fashion history). Du says that she hopes to help normalize wearing qipaos in America.

“The first time I wore my qipao out and about in this country was spring 2021, when anti-Asian hate crime was at an all-time high,” she shares. “I wore a 1950s qipao made in Mainland China [then the new People’s Republic]. It’s made with a light gray wool tweed; a very plain and sensible everyday style, with the only decorative element being the extremely thin contrasting ‘incense’ piping, which is barely visible from a distance. Still, I remember feeling a little nervous about standing out as Chinese, and the subsequent indignation I felt [because of that]. It was really then when I decided to start wearing qipaos more often, as a kind of statement—like, Look, I’m Chinese, and what are you gonna do about it?”

Raissa Bretaña

Raissa Bretaña sees her vintage-heavy wardrobe as an extension of her work as a fashion historian and adjunct assistant professor at FIT. Bretaña is not a historical costumer, but instead brings what she lovingly refers to as “outdated clothing” into her everyday life to show the connections between fashions of decades past and today. When teaching the 1930s to her classes, she’ll bring a lobster brooch or a belt with a hand-shaped clasp as a nod to the Surrealists and Elsa Schiaparelli. “A lot of my work in academia looks at the social history of fashion,” she says. “The practice of me getting dressed in this clothing from the past and living my very 21st-century life is a fascinating sociological experiment every day.”

Bretaña’s Instagram is dotted with vintage, but not of the clearly-from-Depop variety. She wears a blue-and-yellow romper with mid-thigh-length shorts on a Mediterranean yacht; a purple opera coat and fascinator to the Easter Day parade; a crimson 1940s dress and black gloves from 1948 on a train. She finds that people interact with her outfits differently depending on the era. “If I’m wearing a tailored 1950s garment that requires shapewear and petticoats, it does feel farther removed from something we’re more accustomed to today. People react with detached appreciation,” she says. “When I’m wearing clothes from the 1970s, just because of the very nature of that kind of clothing, I feel more comfortable and relaxed in it, so other people are more easy to approach me.”

Christine Millar, M.D.

By day, Christine Millar is an anesthesiologist. In her free time, however, she single-handedly reconstructs 18th-century dresses inspired by Madame de Pompadour (Louis XV’s mistress) and Felicity Merriman (the American Girl Doll). She wears her costumes “whenever I can, wherever I can”: to a ball held at Versailles, where people danced as Marie Antoinette would have; to hear a 1787 Mozart concerto in St. Louis; to make a YouTube video documenting her process.

Millar began as a cosplayer; while attending New York University for undergrad, she would make costumes to attend Comic-Con. Eighteenth-century dresses appealed to her on a visceral level—she liked how pretty and extravagant they were. Reconstructing one can take between 100 and 400 hours, depending on the complexity of the style and embroidery.

Millar is careful to call herself a costumer, not a reenactor (though she has respect for those who interpret history thoughtfully). “I’m not saying I want to live in the past. I work as a doctor and I’m the breadwinner of my family, and that would not be an option for me in that era,” she says. “I love to wear pretty dresses, so that’s at the heart of it.”

Over the past few years, Millar, who is Korean, has seen the historical-costuming community become more accepting of minorities, a shift she partially credits to shows like Bridgerton, which features a diverse cast in elaborate European court dress. “It used to be that I couldn’t go to a single event without someone saying, ‘Oh wait, you’re Asian, you can’t wear that,’ or, ‘There were no Asians in Marie Antoinette’s court.’ That’s why it’s so stupid, because I’m no less close to being Marie Antoinette because I’m Asian than they are,” Millar says. “We’re wearing a costume and pretending.”

Essence

On a recent February day, New Orleans-based artist and burlesque performer Essence was dressed in a Victorian gray waistcoat and skirt, a blouse with leg-of-mutton sleeves, and a small straw boater hat, walking—no, promenading—around the city. Naturally, her 21st-century onlookers were curious. “One guy was like, ‘You can’t be serious,’” Essence says. “I was like, ‘Well, I’m actually very serious about it. I’m literally standing here in front of you dressed like this. In fact, I invested a lot of money into this, so I am very serious.”

Essence seamlessly flits between eras and personas: 18th-century nobility, 1890s Dickens character, 1950s burlesque performer. Her Instagram is a cotton candy-pink cloud of ruffles, corsets, and marabou, only slightly twisted by the two snakebite piercings below her lower lip. She mostly wears vintage day-to-day, and dresses up in 18th-, 19th-, and 20th-century formalwear when she gets the chance.

She doesn’t do it alone. As her interest in historical costuming grew during lockdown in 2020 and 2021, when she was living in Chicago, Essence started to foster relationships with fellow enthusiasts. “Something hits different when you’re with a crew of people that do the same thing,” she says.

Her community was open to people, like herself, who didn’t make their own clothing, but instead purchased reconstructions, and they aligned on key points, such as not dressing up to go to plantations (a situation she describes as “especially relevant” since she moved to Louisiana) and not wearing East Asian dress as someone not of East Asian descent. “Of course, some people would say it’s not my place to wear Western historical things,” she says. “But I like to think that my ancestors were working to make these lifestyles and textiles possible for people, and I get to live their wildest dreams and be the person that partakes in that now.”

Mina Le

It can take a lot to catch a person’s attention on YouTube, but Mina Le’s 1930s eyebrows can stop even the most distracted scroll. Le committed to the beauty look after getting laid off from her job in March 2020. For two years, she’d shave them once a week, then draw on pencil-thin arches in their place. (Now she’s growing them out again, but still recreates the look with “Elmer’s glue stick and concealer, a trick I learned from drag queen tutorials on YouTube.”)

Le describes her style as “theatrical, romantic, and whimsical,” but it goes beyond that. A true aficionado, Le learned about fashion history through thrifted finds; she estimates her current wardrobe is 75% vintage. Her style blends 1930s bloomers, chainmail caps, and fur-trimmed robes with coquettish modern-day clothes from the likes of Simone Rocha and Sandy Liang. The confluence of eras ends up looking almost futuristic—familiar yet unplaceable.

As Le describes it, her idiosyncratic style is a reaction to the way that many engage with fashion in the digital age. “I don’t like to be contained by any particular aesthetic, because I do feel like there’s a lot of pressure these days,” she says. “People want to fall into one genre, one style. They want to have a cohesive Pinterest board. There are silhouettes I’m drawn to, but as a collector, I like to collect pretty things. And there are pretty things that exist in every decade.” And if she gets the odd look or two on the subway? “There are so many chaotic things happening in New York, so it is really the best place to be if you want to dress in costume and not have anyone leer at you.”

Photography & Video: Diana Markosian

Fashion News Writer, Vogue: Sarah Spellings

Visual Editor, Vogue: Olivia Horner

Special thanks to Sarah of Lunar Rose Costuming.

This article was originally published on Vogue.