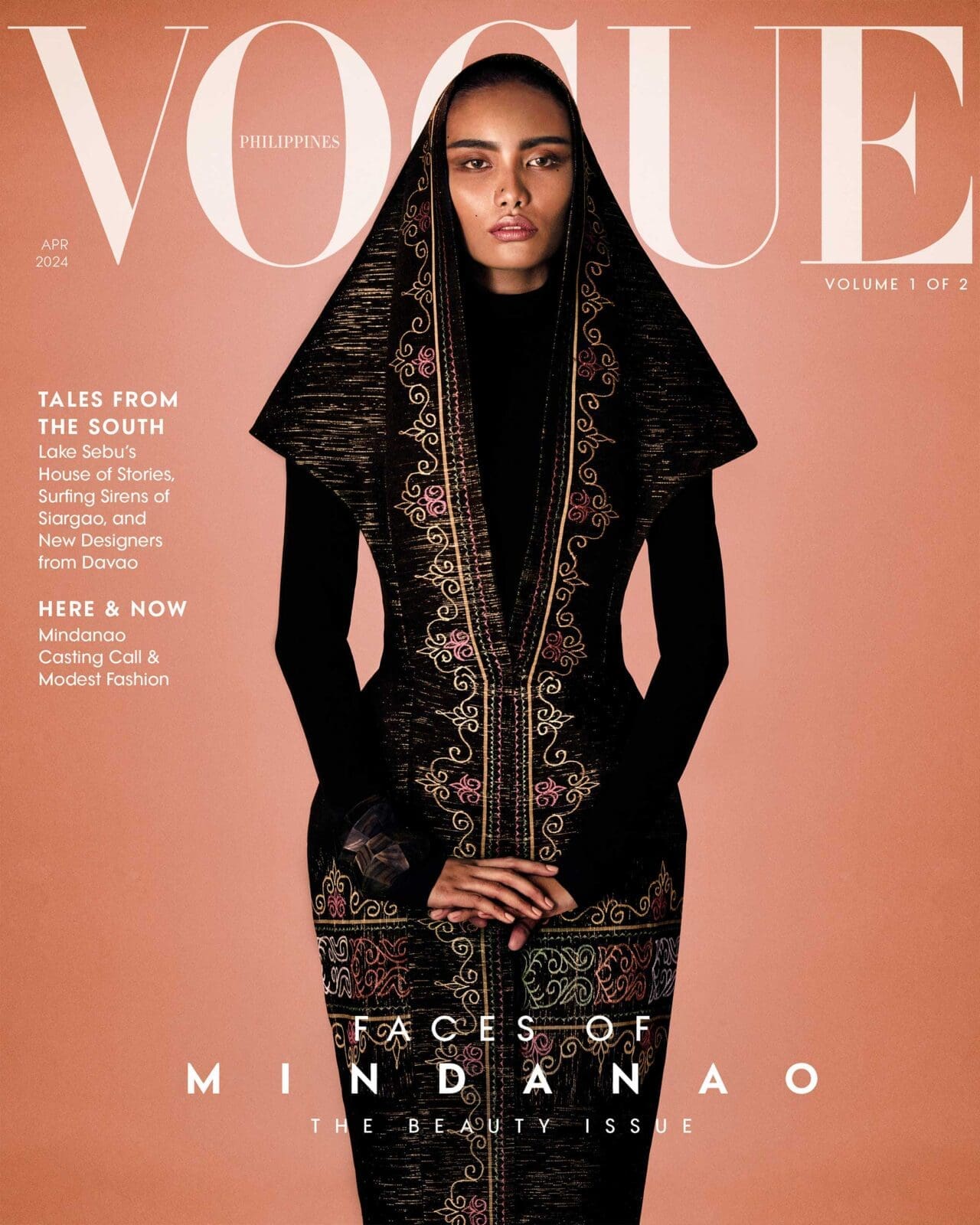

Photographed by JOSEPH BERMUDEZ for the April 2024 Issue of Vogue Philippines

Photographed by JOSEPH BERMUDEZ for the April 2024 Issue of Vogue Philippines

For Maricris Brias, honoring ancient techniques drives legacy.

Maricris Floirendo-Brias didn’t intend it, but she would eventually be the one to carry out her father’s legacy. In the mid-1900s, Don Antonio O. Floirendo Sr. established the Tagum Agricultural Development Co. or Tadeco as an abaca plantation in Mindanao, before deciding to shift to bananas. When Maricris returned home after earning a degree in graphic arts from Goldsmiths, University of London, she worked in advertising, then moved to Davao after she got married. It was when the couple settled down that she developed an interest in Tadeco’s agricultural waste.

“In the livelihood, they were weaving banana fiber, abaca curtains, and making stuffed toys, and so I looked around. I wanted to use whatever waste was coming out of the plantation,” she explains.

When Maricris assumed leadership of Tadeco Livelihood and Training Center in 1989, she aimed to provide employment opportunities for the wives and dependents of Tadeco’s plantation workers. At present, she serves as the creative director of Tadeco Home, a brand under Tadeco Livelihood.

For one of her projects, they gathered banana leaves and stalks to create paper “because that’s the simplest and the most basic thing to do with fiber.” Rolls of textured sheets are printed with patterns mimicking weaves by the indigenous Yakan, Tboli, and Mandaya communities. They come in earth tones, harking back to the process of natural dyeing with turmeric, ginger root, and elderberries. They make great gift wrappers, says Ella Aguinaldo, who mans the shop in Davao’s Abreeza Mall.

“She loves to do underwater features,” Ella says of Maricris, pointing to the under the sea collections and award-winning coral panels. Growing up around the sea and nature, its elements inspire her to this day and figure even in little details like mother-of-pearl or coco beads embellished on cushion covers.

Over time, Maricris’ fascination with indigenous weaves, particularly of the Tboli and Mandaya groups, grew. “I wanted to help them out and preserve their crafts, because young people didn’t want to weave anymore. Most of them would rather work in supermarkets and have blue collar jobs,” she says.

To support them, she started off purchasing their fabric: Tnalak from the Tboli and Dagmay from the Mandaya, which she fashioned into pillow covers and soft furnishings. Later on, she began collaborating with the artisans to create products for the brand. She also works with the Matigsalug for basketry, though they’re still in the early stages of perfecting their craft. Even so, Maricris continues purchasing their work in the hopes that they’re encouraged to keep practicing their skills. “I always like to use their material more than anything else so they continue weaving, she narrates. “And I guess it helped. The young people started to weave again.”

The materials Tadeco uses are sourced from the farm (apart from wires used for the coral panels), and all indigenous weaves come straight from the weavers. The various materials allow her to experiment with her designs, which is her favorite part of the process. She enjoys exploring how far she and her artisans can go with a certain idea until they eventually find what works. When she showcases Tadeco’s products abroad—in Paris, most recently—they’re appreciated for the distinctiveness of the material and make.

A big part of that exploration is honoring heritage techniques from the past and innovating them for the present. For Tnalak, it takes weeks alone to dye the abaca because they make use of organic dyes. Afterward, the abaca fibers are handwoven using backstrap looms. A long, narrow tapestry can take up to six months from connecting, tying, dyeing, and weaving the fibers, says Myrna Marcelo, a Tboli weaver who works for Tadeco and is assigned to the Marina Pearl Farm in Davao. “Mas matagal dito [It takes longer here],” she explains, comparing the weaving timeline to that of Lake Sebu where she’s from. She takes a break in the afternoon when the sun is high, because the humidity and salt in the air cause the abaca to dry out, become fragile, and break off.

In Lake Sebu, the weavers follow a similar schedule. Maricris says they have a tendency to weave in the early morning or late afternoon when it’s cool, which is why production takes time. “I don’t remove them from their village, from their community,” she reveals, speaking about their collaborators: over 400 Tnalak weavers and over 200 piece rate workers. “I let them weave in their environment alone. You can’t stop their way of life. You have to keep to that.”

By Ticia Almazan. Photography by Joseph Bermudez. Photographer’s Assistants: ADI ADE GRACIA, ELLAH PLARIZA. Production Assistant: PATRICIA VILLORIA

- Weaved Lives: The Rich Cultural History of The Tnalak Fabric Woven By The Tboli People

- South Bound: Mindanaoan Designers Goldie Siglos, Wilson Limon, and Steffy Misoles-Dacalus On Their Beginnings In Fashion

- Craft Corner: The Weaving Tradition Of The Yakan Village In Zamboanga

- Modesty: Mindanao’s Myriad of Design Languages In Fashion