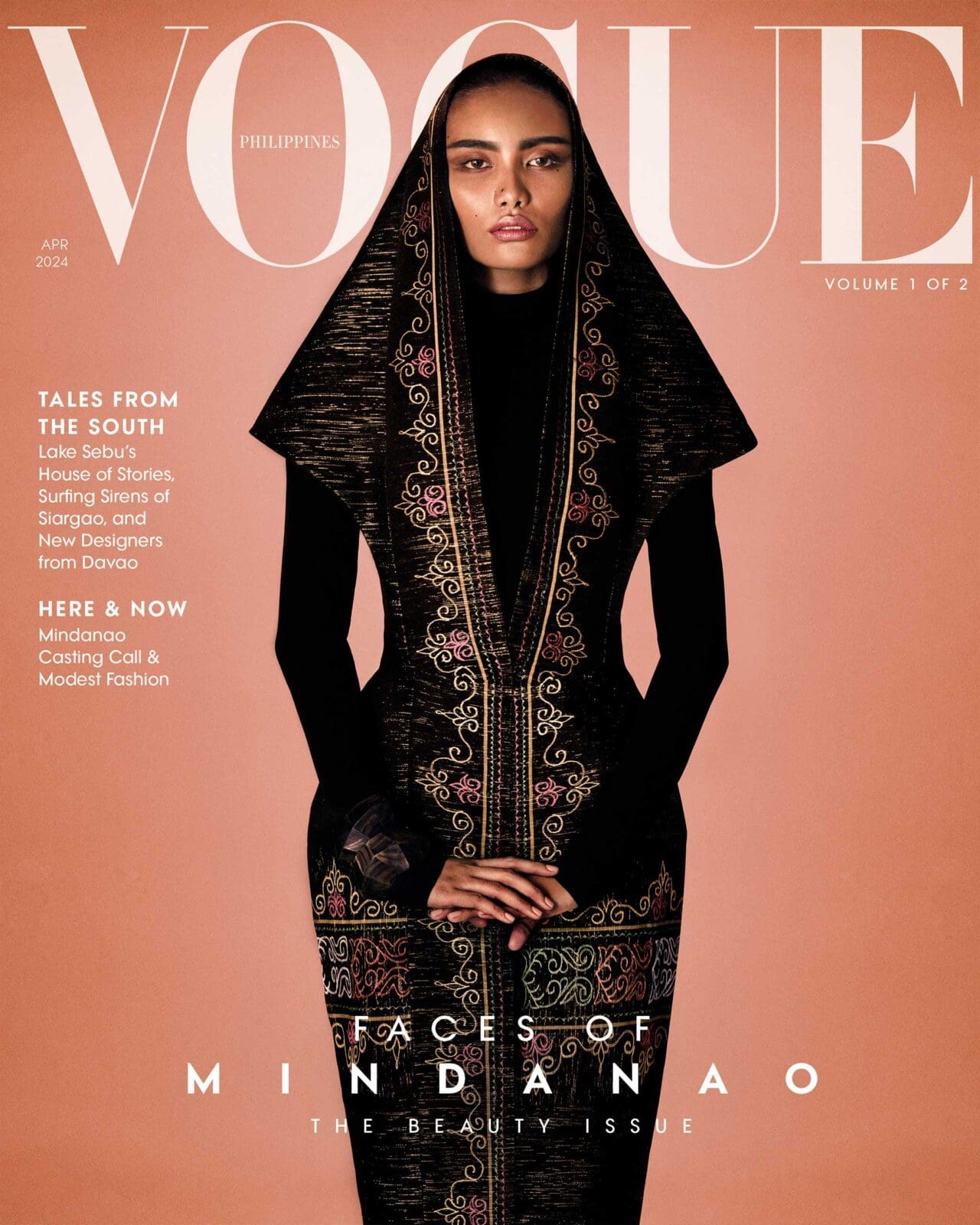

Linda Weaver, Hester Jabagat, and Jasmine Metano with the next generation of Tboli Musicians. Photographed by GABRIEL NIVERA for the April 2024 Issue of Vogue Philippines

Photographed by GABRIEL NIVERA for the April 2024 Issue of Vogue Philippines

Inside the Tboli house, the sound of the spirit echoes through the Tboli people’s music. In Vogue Philippines’ April 2024 issue, learn the story of Linda Osman Weaver as she walks us through Gónô Sbung, the House of Gathering.

When you enter the Tboli house, the first thing you see is the hearth, a firepit placed right in the center of the home. Pots of kamote and coffee simmer over the fire while dogs and cats laze around. Displayed on a shelf are ears of native corn, tasseled baskets, boar mandibles, and monkey skulls. Colorful Maranao-style canopies hang above several mattresses, which can sleep up to 50 persons. The tinkling of bells, the thrumming of lutes, and the beating of drums being to energize the space. Welcome to Gónô Sbung, Linda Osman Weaver’s House of Gathering.

“This is the house of all family,” Linda says, describing how she had gone through previous iterations of her gónô but was never satisfied because it was either too small or too leaky. “So this is the last one, my dream come true.” The house is a recreation of a traditional gónô bong (big house) where a datu would live, each wife given her own cubicle for sleeping with their children. The house would also be large enough to hold the monimun, a major ceremonial wedding ritual that occurs over several days. Gónô Sbung hosted a tribal wedding last December, she says, and were able to fit 200 guests.

In 2016, Linda was nominated for the Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan for the klintang (set of eight knobbed gongs). She does more than play the klintang, however, she chants, she dances, and is proficient in all the music arts that she teaches at the Gónô Sbung. She tells us that her mother was a dreamweaver who would exchange designs with Lang Dulay, the first Tboli artist to be given a GAMABA. Despite what Linda’s surname may imply, “I never took to the tnalak,” she says. “For me it was always the music.”

Her journey towards high status as a culture bearer, who has performed in Singapore, Italy, New York, and Russia, was not without its share of struggles, in large part due to her being female. “I couldn’t finish school because I was 12 years old when I was arranged to be married,” Weaver says. “What the clan decides must be followed.” The girl was later accused of committing adultery, but somehow, through an indigenous ritual involving the ordeal of boiling water, she was vindicated before a traditional tribunal. “That was when the community started respecting me and regarded me highly as a Tboli woman.”

She separated from her first husband and resumed her studies at the Santa Cruz Mission, only to be married off again at the age of 18 to a Bicolano merchant three decades her senior. “Even though it was an arranged marriage, I learned to love him, because he was a very kind man, and he gave me everything I needed.” If it weren’t for him, she says, there wouldn’t have been a Gónô Sbung, her advocacy and legacy. “All things work together for the Lord.”

The Weaver grandchildren, who have started their musical education at an early age, are already seasoned performers. Linda’s daughter-in-law shows us the kadal tahaw, a dance that imitates the movement of the tahaw bird whose call sounds the start of planting season, while her three-year-old daughter joins her older kuyas in the warrior dance. A boy of around eight plays the kubing (jaw harp).

“I’m not very strict about learning the melody,” Linda says. “As a Tboli musician, there are no notes.” She continues, “We make our own music, dream our own music. Not only the dream- weavers dream—I dream my own sound, with the sound of the wind, the river, the falls, the sound of the birds.”

Tboli art cannot be separated from the environment. Everything in nature, and even objects like musical instruments, possesses a spirit. A river can’t be crossed without first seeking permission, and Tboli do this by picking up a stone from the river and touching it to their head. “You have to touch, you have to connect, otherwise you might get sick or suffer misfortune,” Weaver explains. Before every dance, the dancer taps the tnonggong (deerskin drum) with a foot so that the dancer and the drummer will be filled with energy. At the end, the drum is tapped again, paying respect to fu tnonggong, the spirit of the drum.

Non-indigenous people may shrug these practices off as superstitions, but there is wisdom and truth in animist consciousness. We have lost touch with nature. We have destroyed our connection with the environment. And we are getting sicker for it, living on a rapidly warming planet whose side effects have been catastrophic. “In the context of Tboli traditional religion…the spiritual suffuses reality, making everything sacred and worthy of respect,” writes Manolete Mora, one of the ethnomusicologists who have helped outsiders understand the musical structure of precolonial Philippines.

When Tboli musicians like Linda dream their music, it is the sound of the spirit, the sound of prayer, it is the sound of the universe humming back to you.

By AUDREY CARPIO. Photographs by GABRIEL NIVERA. Producer: Patricia Co. Photographer’s Assistant: Adrian Dan. Special thanks to the Municipal IPS of Lake Sebu, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples, SOAS University of London, Comm. Reden Ulo of the NCCA, Marian Pastor Roces, Benjie Manuel, Hermelyn Jabagat, Cristina and Jovi Juan

- Weaved Lives: The Rich Cultural History of The Tnalak Fabric Woven By The Tboli People

-

South Bound: Mindanaoan Designers Goldie Siglos, Wilson Limon, and Steffy Misoles-Dacalus On Their Beginnings In Fashion

- How the Vogue Philippines Casting Call Found Fresh Faces of Beauty in Mindanao

- Capturing A Modern Mindanao: Behind The Lens of Neal Oshima and Mark Nicdao