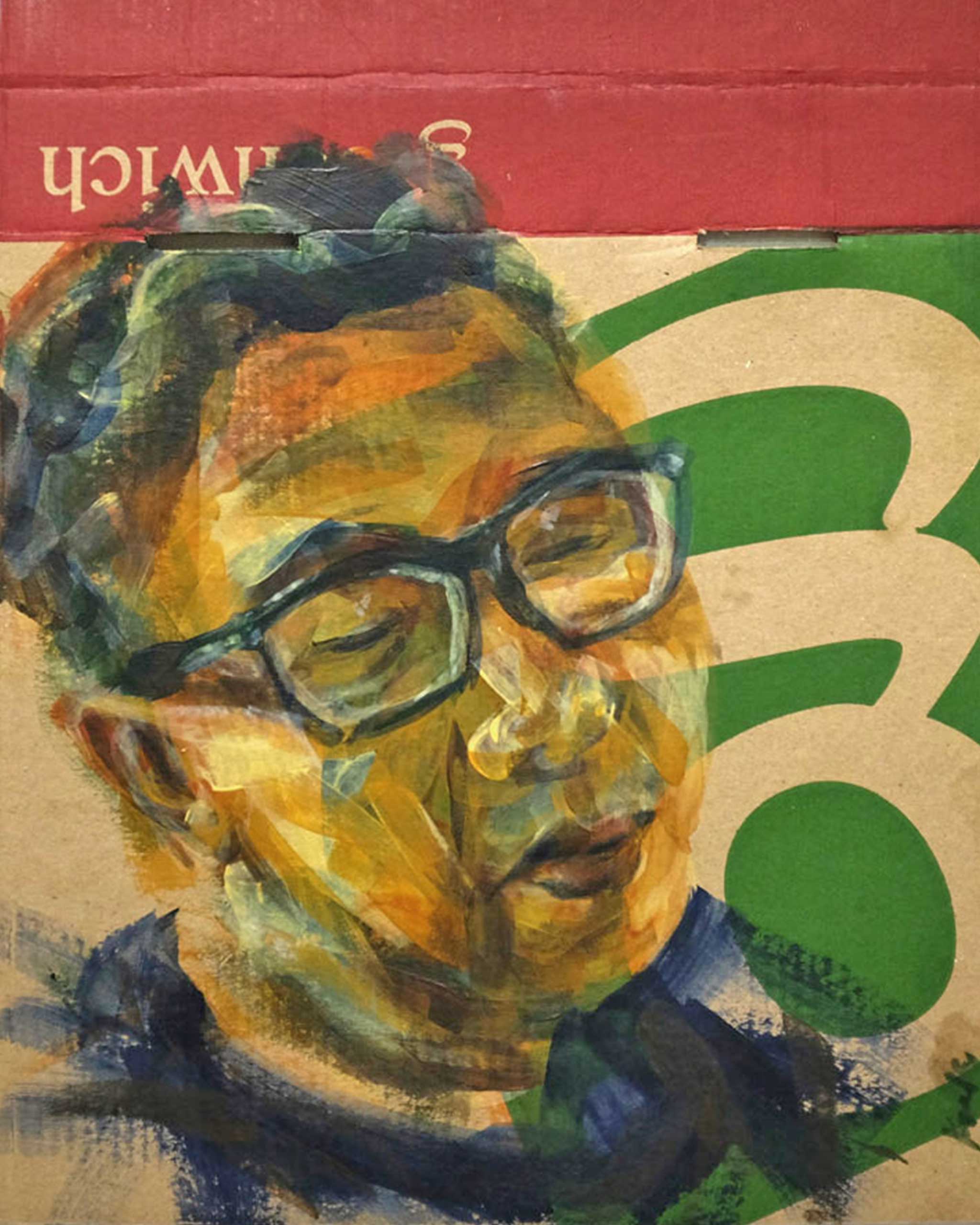

Courtesy of Karl Castro

“To me, Floy was a most constant supporter, a generous mentor, and a funny confidante.”

I look at the little wooden buddha on my desk, and I remember Floy Quintos. This was the last gift he gave me, one of the many “cheap and cheerful” things, as he would call it, that we exchanged, spurred in turn by my pasalubong to him from Japan: a book on folk gods and buddhas from northern Tohoku. This trade of arcane finds has come to be our kind of love language over the years. To me, Floy was a most constant supporter, a generous mentor, and a funny confidante.

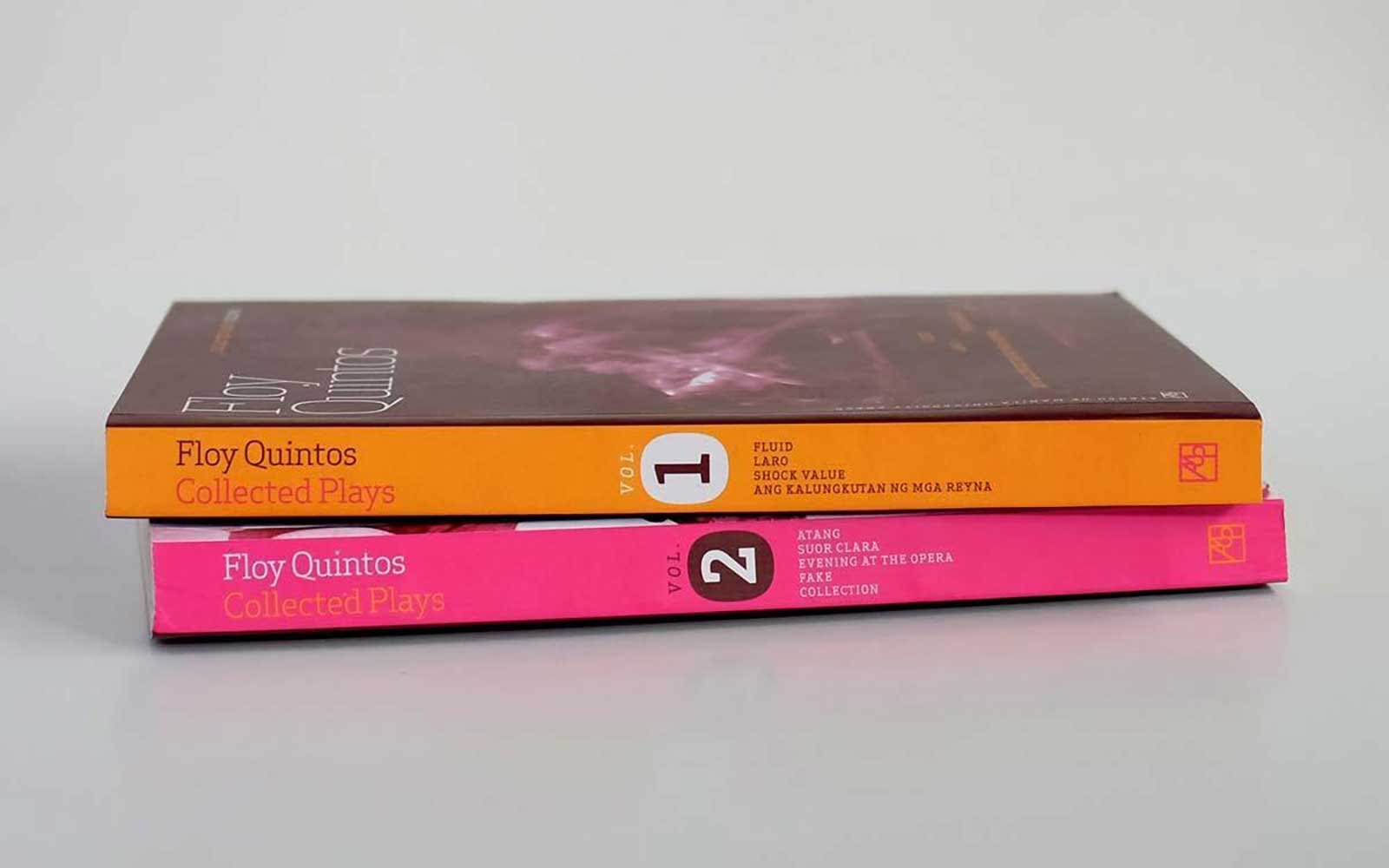

I first met him in 2012, when the Ateneo de Manila University Press invited me to design his collection of plays. He was an accomplished playwright and director, but I had not had the chance to see his plays at the time. Given the scarce budgets of my student days, I had generally read more plays than seen them—and his, I discovered, were compelling, incisive, emotional. The book eventually came out in two volumes two years later. Since then, Floy and I have worked on several other book and exhibition projects loosely centered around his other forte: traditional arts of the Philippines.

In all of these, I was both an eager student and a happy collaborator. I felt privileged to somehow deserve his trust, and he was utterly lavish with words of encouragement and support. In 2016, the Filipinas Heritage Library hosted a retrospective of my body of work in designing Filipiniana books, and Floy’s collection was among the books I chose to feature. He graciously shared his time as one of the documentary subjects, and lent many precious objects from his own collection, like textiles, jewelry, and amulets, among others. These were instrumental in visualizing my design process from inspiration to print.

In my own way, I would also try to support him, usually through design tasks or research. Anything related to his interests which I’d find while trawling archives, museums, and flea markets, I’d message him in real time. From Cristóbal Balenciaga to Oceanic art, Chinese propaganda posters to bizarre pageantry, everything was fair game. Our unbridled discussions on his productions and random fascinations would sometimes find their way into fledgling projects. Around a decade ago, I had randomly shared with him my childhood fascination with the 1948 apparitions at a Carmelite monastery in Lipa, Batangas. I lent him materials, and over the years, it became fodder for what would become his final play, Grace, set to open next month.

Since I was a kid, I’d been endlessly fascinated by ancient cultures and places, but their artifacts always seemed to be out of reach, only accessible to me through books and museums; my friendship with Floy changed that. He introduced me to a more sensory appreciation for Philippine objects: the texture of a bulul’s [granary guardian] crusty patina, the smooth bone hilt of an old kris [double-edged blade], the weight of an heirloom pilakid [beaded body jewelry]. More importantly, he reminded me of the value of their context: the promise of food on the table, the defense of one’s homeland, the celebration of wedded bliss. While other collectors would simply obsess over rarity, age, or fine craftsmanship, Floy taught me to never forget that the most precious dimension of each object was immaterial.

What fascinates me about antiques is not just their artistry; it’s also the strange circumstances which led them to somehow endure. In the Philippines, we have a trillion possible factors leading to inevitable and entropic loss: wars and calamities, colonizers and dictators, displacement and desperation. Sometimes, just sheer neglect. All things considered, it’s nothing short of magic to realize that one can still finger the ridges of a duyu [star-shaped food bowl], see traces of plant dye on a fragmentary shroud, or hold a small hapag [ritual figure] in one’s palm.

People, however, are a different story. When they’re gone, that’s the end. Chats and mementos, the very things that remind you of their presence, are suddenly signifiers of absence.

In one of our last chats, Floy shared that he was nearly done renovating his home in anticipation of his sunset years. “No more antique furniture,” he said. “Even the red cement floors. Babu na.” What he looked forward to was “handrails sa banyo” and “windows that work.” Renowned purveyor of fine objects that he was, it was the simpler things he truly looked forward to. Cruel to know now that those “tander diva years” would cease to come.

We never really took pictures together, so I now take solace in this recording from 2016 for my solo exhibition on book design. Perhaps I’ve taken his voice for granted all these years since we chat so often. I have many keepsakes from our years of friendship, but none of them, not the carved buddha or the little hapag, can answer back. But this video reminds me, in his own words and laughter, that he was my dear, dear friend. The immaterial.

17 April 1961–27 April 2024

- They Remind Us of Who We Once Were and Truly Are

- A Remarkable “His and Hers” Collection of Antiquities That Weave the Stories of Philippine Nationhood

- Connecting Threads: How To Preserve Craft Will Survive For Future Generations

- Weaved Lives: The Rich Cultural History of The Tnalak Fabric Woven By The Tboli People