Image courtesy of Edwin and Aileen Bautista

Salcedo Auctions launches its Private Art, Public Lives exhibition series with the collection of Edwin and Aileen Bautista

“The death mask should stay in the frame, not made into a necklace. It’s one of Edwin’s rules,” Aileen Bautista states, addressing a question that was on everyone’s mind. “It’s sagrada for me, too.” Mrs. Bautista, a professor, had just been describing how she got into collecting pre-colonial gold jewelry—she started tagging along with her husband Edwin on his hunts at antiques shops at the La’O Center, should he take home another haunted old relic which they had nowhere to keep. “But then, during that time, ako ang nabudol (I was the one who ended up buying in),” she jokes.

Her own requirement for collecting jewelry was that they had to be wearable. Aileen was first introduced to colonial gold jewelry like tambourines, then from historian and art dealer Ramon Villegas, learned about our wealth of pre-colonial gold. She was amazed at the craftsmanship from the 10th century, skills that were previously thought to have been learned from the Spanish. “There was so much gold in Butuan, Surigao, Samar. We were so rich in gold that we traded it with the Chinese for plates.”

Until September 3rd, the Bautistas’ private collection—or rather a select part of it—is on view to the public at Salcedo Auctions. Curated by director Floy Quintos, the wide-ranging exhibition pieces are connected through a narrative of evolving nationhood, threading the pre-colonial to the colonial to the revolutionary, with all the spirituality that permeates these objects throughout.

Aileen’s contribution is the gold jewelry that showcases sophisticated techniques like filigree, granulation, and repoussé. The majority of gold artifacts in the Philippines were unearthed in undocumented excavations and literal grave robberies, but many pieces ended up being bought by known collectors Jaime Laya and Leandro and Cecilia Locsin, later becoming part of the Central Bank and Ayala Museum collections respectively. It was only in 2010 that a law was passed prohibiting excavations not sanctioned by the National Museum.

On the “his” side of the exhibition, Edwin Bautista, President and CEO of UnionBank, unveils his collection of religious art, maps, weapons, and flags. Notable are the mamarrachos (grotesqueries) and imagenes repulsivas (repulsive icons) from the late 19th to mid-20th century. These are Catholic icons that were carved by unschooled artisans outside of the established santo-making workshops. Priests considered them ugly and unacceptable and refused to bless them. Director Quintos was the first to take note of these folksy pieces being in an art class of their own. A humorous example is an interpretation of the Archangel Michael slaying the demon, which seems to have been lifted directly from the logo of a Ginebra San Miguel bottle (a logo which incidentally was designed by a young Fernando Amorsolo).

Also fascinating is the room dedicated to anting-anting (an amulet against spirits), revealing how Filipinos practiced an indigenous belief system that blends Catholicism with folk mythology and other influences. A secret language of resistance, revolutionary fighters went to battle armed with only bolos and anting-anting vests, sandos drawn over with images of the Infinita Dios and incomprehensible Latin phrases.

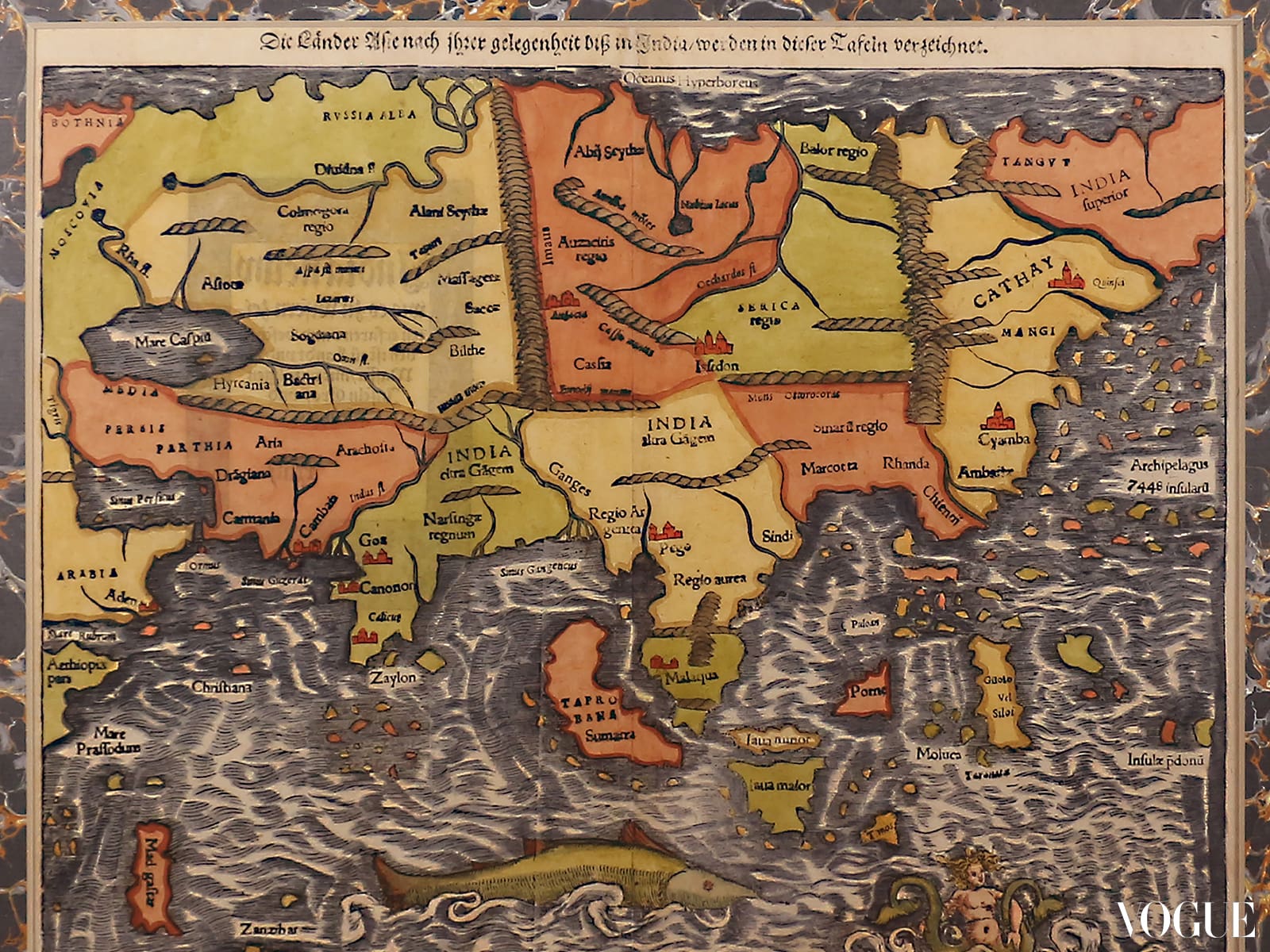

Mr. Bautista’s archive of rare maps, meanwhile, reconstructs the emergence of the Philippines as it was represented to the world. The 1563 Ramusio-Gastaldi map, for instance, is the first printed map of the world to mention Filipina. “It’s referred to as the Philippines’ birth certificate,” Mr. Bautista says. Also on display is the 1849 Coello map that was used by the Spanish and the Americans during the negotiations for the purchase of the Philippines in the 1898 Treaty of Paris.

Near the maps is a small sword collection that Mr. Bautista dubs as a relaunch, as he had previously donated his entire stockpile of around 1000 bladed weapons to the Museo ng Kaalamang Katutubo, a collection which is described as “shockingly beautiful” by Marian Pastor Roces. “But,” Mr. Bautista shares, “my foreign dealers would still email me with photos of rare and important specimens (war trophies by Spanish and later American soldiers). Should I acquire them to repatriate back to our country, or leave them abroad, never to be seen and appreciated by Filipinos?”

And therein lies a big part of why the couple collects, and why they are exhibiting—not selling— their collection to the public for the first time. “Through exhibitions like this, we can breathe new life into these relics, infusing them with relevance and meaning,” Mrs. Bautista says. “Edwin and I always approach our passion for collection with humility. In the end, if I may say, it’s not about the value, or rarity of the objects. It’s about the joy of discovery, the thrill of the hunt, and the stories that have been lost along the way. Most importantly,” she adds, “ it’s about preserving our cultural heritage and ensuring that our present and future generations can appreciate and learn from the rich history of our ancestors.”