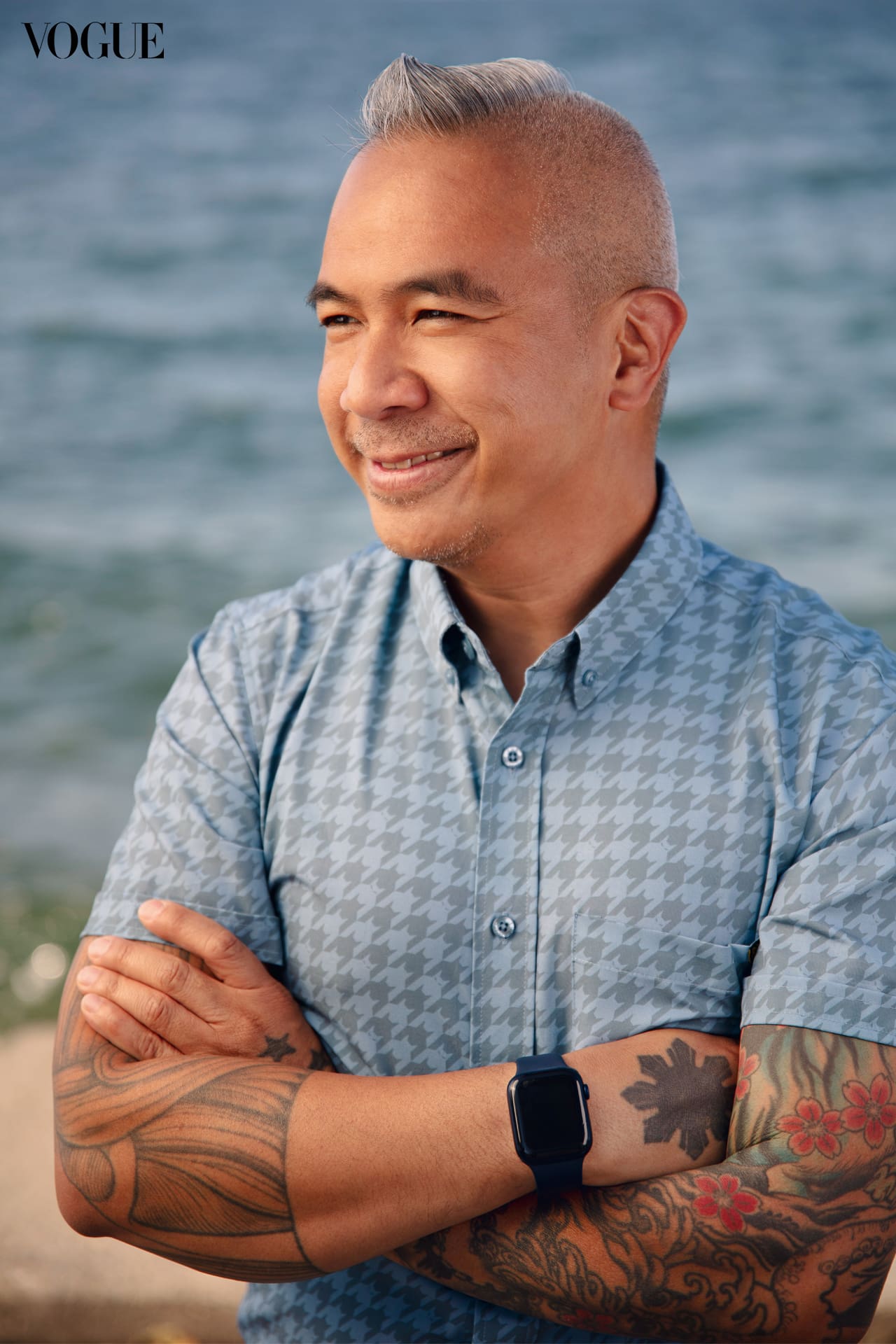

Ben Lucas

Meet the Senior Design Manager at Roblox, one of the fastest growing and most inclusive platforms in the metaverse.

Before memes of famous personalities photoshopped into major events became a thing—Bernie Sanders in mittens sitting on the Iron Throne, former presidential aide Bong Go photobombing every group photo in history—there was Bert Is Evil.

In the wee years of the Internet, March 1997 to be exact, a 23-year-old Filipino digital artist named Dino Ignacio created a conspiracy-themed website proving that the Sesame Street character was actually sinister. Photos of the unibrowed muppet fraternizing with villainous figures like Adolf Hitler or being mysteriously present at events like the JFK assassination became a proto-viral sensation, and people began contributing their own images of Bert in compromising situations. A year later, Ignacio won a Webby Award for best website in the “weird” category, besting The Onion.

And weirdly enough, a photo of Bert with Osama Bin Laden was spotted on a poster at an anti-American protest in Bangladesh in 2011. It was so controversial that The New York Times wrote about it, pointing out that while Ignacio did not make that particular image, he had to shut down the website to stop the madness.

In his goodbye post, Ignacio explained that he cared about what children thought of Bert. He never expected that his funny little site with a cult following would become a flashpoint in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. He was inundated by reporters from all over the world. It was the first time the boundary between the internet and reality began to blur.

“I just killed the rebellious part of my soul today,” he wrote after taking the site offline, “in lieu of the part that dictates to be responsible.” (He probably didn’t expect the site would be forever archived by the Wayback Machine.) Ignacio closed with, “Don’t worry, there’s more where it came from.”

Social hub

Twenty-five years later, that “rebellious punk” now leads at Roblox as Senior Design Manager. Roblox is a metaverse platform with over 52 million daily active users, including Dino’s and my own children. Not surprisingly, the Philippines is ranked as one of the top seven countries with the most hours of engagement.

Roblox is a major social hub for the youth, and because of that, brands from Nike to Givenchy have entered the space, launching virtual products, experiences, and capsule collections for players to spend (their parents’) real money on. Last year, a digital Gucci bag was resold for $4,115 inside the game (originally bought at $6 or 475 Robux). These items only live online for avatars to flex; there is no real-world in-store redemption.

“It’s fascinating, right?” Dino says, trying to explain to me the nature of this phenomenon by comparing it to NFTs, which tap into the value of digital scarcity. “People are drawn to them because there’s a perceived value to the purchase. And NFTs succeed on that level. But the other reason why people buy things is because they want the affirmation, they want to flaunt and show them off. The value of the object is partly extrinsic and also intrinsic—how it makes you feel when people see you with it. And that’s the part NFTs fail at right now.”

Tell that to the bros with 1×1 profile pics of pixelated monkeys.

“That’s where Roblox comes in,” Dino continues. “So I’m in a virtual world and not only can I own an item that is scarce, but I can walk around and socialize with it.”

“It’s a great win for creative expression, and most importantly, for inclusion”

Creative expression

At the time of our Zoom call, Dino is fresh off the Roblox Developer Conference in San Francisco, an event the company holds for game developers to showcase the platform’s latest features. Much of what he has been working on includes new ways to express oneself in the worlds of Roblox, for instance, a feature called Layered Clothing allows developers and creators to make clothes that fits any avatar body type, whether it be a classic blocky or a T-Rex, a small child or a muscular creature. It also lets players mix, match, and layer items of clothing, just like they do in the real world.

“It used to be that if a designer made a dress or a female presenting outfit, it would only work with a female presenting avatar shape. But with this new technology, any body type is valid for whatever you want to wear. And that’s really been exciting for me as a technology,” he says. “It’s a great win for creative expression. And most importantly to me, for inclusion.”

Last year, Harley, Dino and his wife Nina’s only child, announced to the two parents that they were non-binary. The parents were supportive and proud, with Dino posting on Facebook the occasional anecdote like how they created a tip jar for when he or Nina would use the wrong pronouns, with the accumulated money to be donated to an LGBTQ youth organization. These kinds of posts opened up honest conversations among the Gen X parents of Facebook and served as a learning model for how to be your own child’s ally.

The news was not wholly unexpected, Dino tells me now. Over the pandemic, he and Harley shared an iPad at home on which they both used Roblox, one for work, the other for play. If Harley forgot to log out, Dino would notice that their avatar would change from being female presenting to male presenting to gender neutral over several weeks.

He also would see that they had joined certain LBGT communities within Roblox. “So it didn’t come as a surprise when they eventually came out to us, but the fascinating thing about all this for me is, I think Roblox afforded my child the ability to experiment on their identity in a very safe way,” Ignacio says.

His professional involvement with Roblox bleeds into the personal. Dino first looked into the company because he noticed his kid getting into it, but he’s now invested in keeping the platform safe from offending content and bad actors. “I didn’t get into all this to end up in a world where my child is playing a game that doesn’t feel safe,” he says. “So I’m always looking out for that. And my number one customer is my child.”

To give an example of how conservative Roblox is: any words that show affection, like “love,” are hashed out. My daughter confirms that strings of numbers are also censored. “We don’t want the platform to be a place for grooming,” Dino explains. “We have a very robust trust and safety team that constantly monitors and moderates and makes sure that no illicit behavior occurs on the platform.”

Thoughtful growth

After graduating from the Academy of Art in San Francisco in 2005, Dino had originally hoped to become a film animator but ended up in the burgeoning video game industry, spending six years at Electronic Arts before moving to Oculus as a VR designer. Oculus was acquired by Facebook, and there Dino advanced as a design manager for Facebook Spaces, Facebook Horizon, and finally the Avatar design team.

As Facebook grew, so did the number of scandals it was embroiled in. He started to feel less aligned with the morals and ethics of the social media giant and was uncomfortable with what he felt was proving to be an unsustainable and increasingly toxic workplace culture.

Facebook, now Meta, still runs by the Mark Zuckerberg hacker-era motto “move fast and break things,” an ethos that favors speed and disruption. Dino describes how employee performance is assessed every six months, and if you didn’t ship anything, you’re not going to get a good review. “So they’re always trying to game the system by releasing something early,” he says. “I know they’re actively trying to change that culture, but it’s been ingrained for a while, and it’s very damaging to mental health, to the quality of the product, and to the relationships you have with people. It’s a very cutthroat way of getting things done.”

Not a lot of people may know that Roblox, as a company, is as old as Facebook, both being founded in 2004. Roblox took the slow route, growing organically and thoughtfully. “One of the values of the company is taking the long view,” Dino says. “I heard it talked about a lot when I first got there, and at first I thought, well, that must just be lip service.”

After working there for a year and a half, Dino can say he’s seen this value demonstrated in many ways. Dino and his team were supposed to launch Layered Clothing sooner but held it back in favor of doing more testing. “There’s so much consideration that we put into the product. Slowing down a product release is just as impactful as speeding it up.”

This attitude provides designers the ability to decelerate and really think about their audience and how they’re being served.

With his job at Roblox, Dino is also able to spend more time with his family at home in Seattle and see his now 11-year-old kid grow into themselves, which, it turns out, is not exactly a clone of him. “From the outside, it seems like my kid loves Star Wars as much as I do. And that’s really not the truth,” he admits, referring to the many Comic Cons they’ve attended together, all cosplayed out. “My wife and my kid just tolerate me. I’m just glad it lasted as long as it did.”

To commemorate the 25th anniversary of Bert Is Evil in March this year, Dino decided to mint a few NFTs of evil Bert which, so far, remains available to purchase on Foundation. To be fair, Russia had just invaded Ukraine and it’s been a terrible year for crypto in general.

“Maybe I just don’t understand NFTs. I was too late,” he notes, an odd thing to hear from someone who’s been on the cutting edge of the American tech industry for nearly two decades. Dino may have missed the NFT wave but he’s working on things more important: honing a new generation of designers who honor their craft and safeguarding the digital lives of our offspring, as more of it is lived in the metaverse. The rebellious part of Dino’s soul never died; it was transformed.

With the current discourse over screen addiction and social media induced depression, I ask Dino if he’s optimistic about technology.

“I’m stealing this from somebody else: ‘I’m a short-term pessimist, a long-term optimist,’” he replies. “I look at the world and I see what’s wrong and it drives me to come up with better solutions. I’m like, why are people doing it this way? Or, this product is broken, or this is no way for children to be interacting on the internet.”

He continues, “I find a lot of pessimism in technology. But for the long term, I keep thinking about how it could be better and I’m driving towards that. My long-term goal is always about using technology to bring good.”

Don’t ask me how, but I’m pretty sure there’s more where that came from.

Photographs by Ben Lucas

This article was originally published in Vogue Philippines’ November 2022 Issue, available for purchase now.