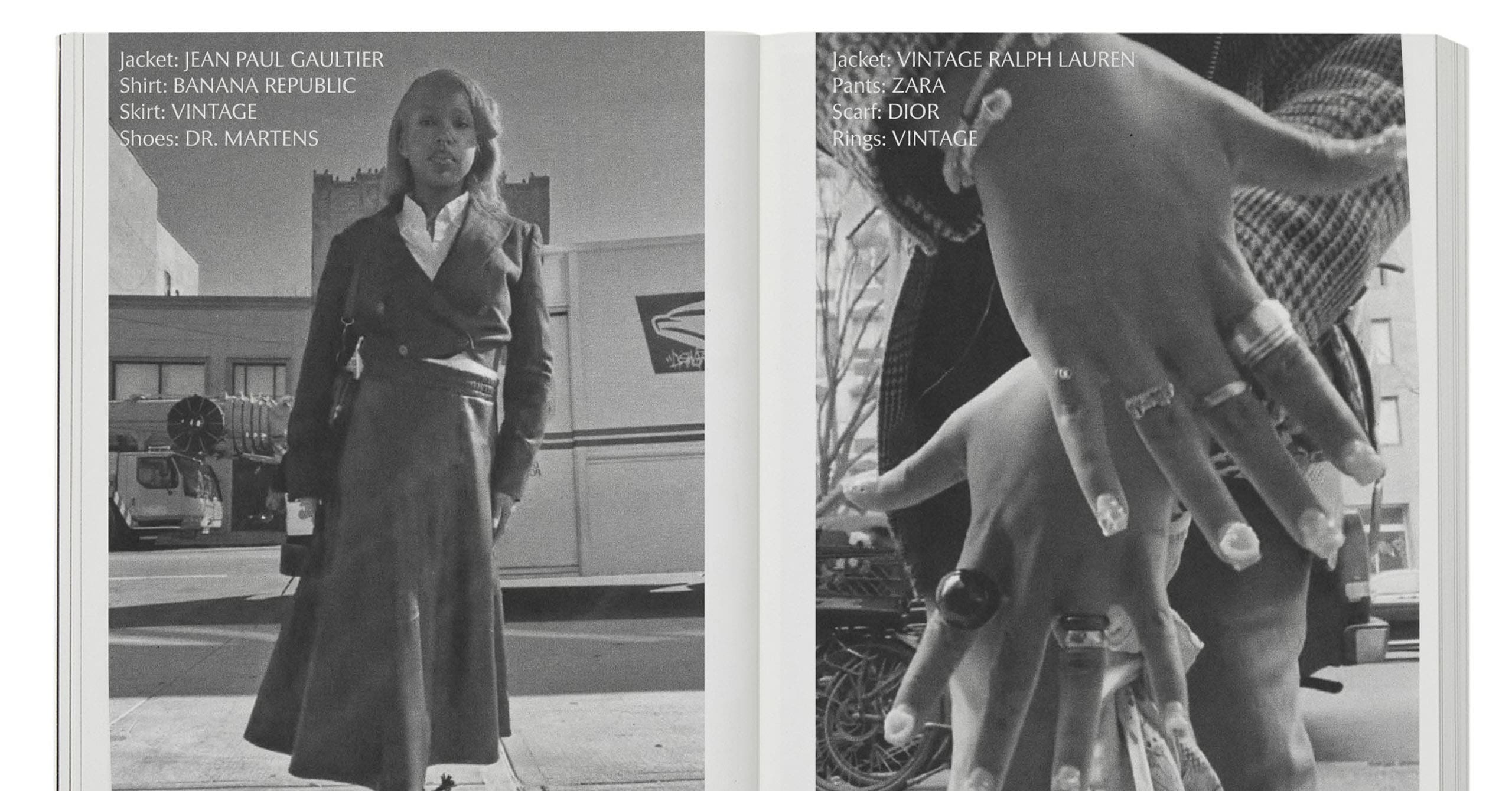

Photographs by Skye Laila. Photo: Skye Laila / Courtesy of Nuts Magazine

Photographs by Skye Laila. Photo: Skye Laila / Courtesy of Nuts Magazine

Nuts. The last magazine to call itself that was an early-aughts British lad mag. Now a New York–based independent initiative from Richard Turley has taken up the name for a very different kind of publication.

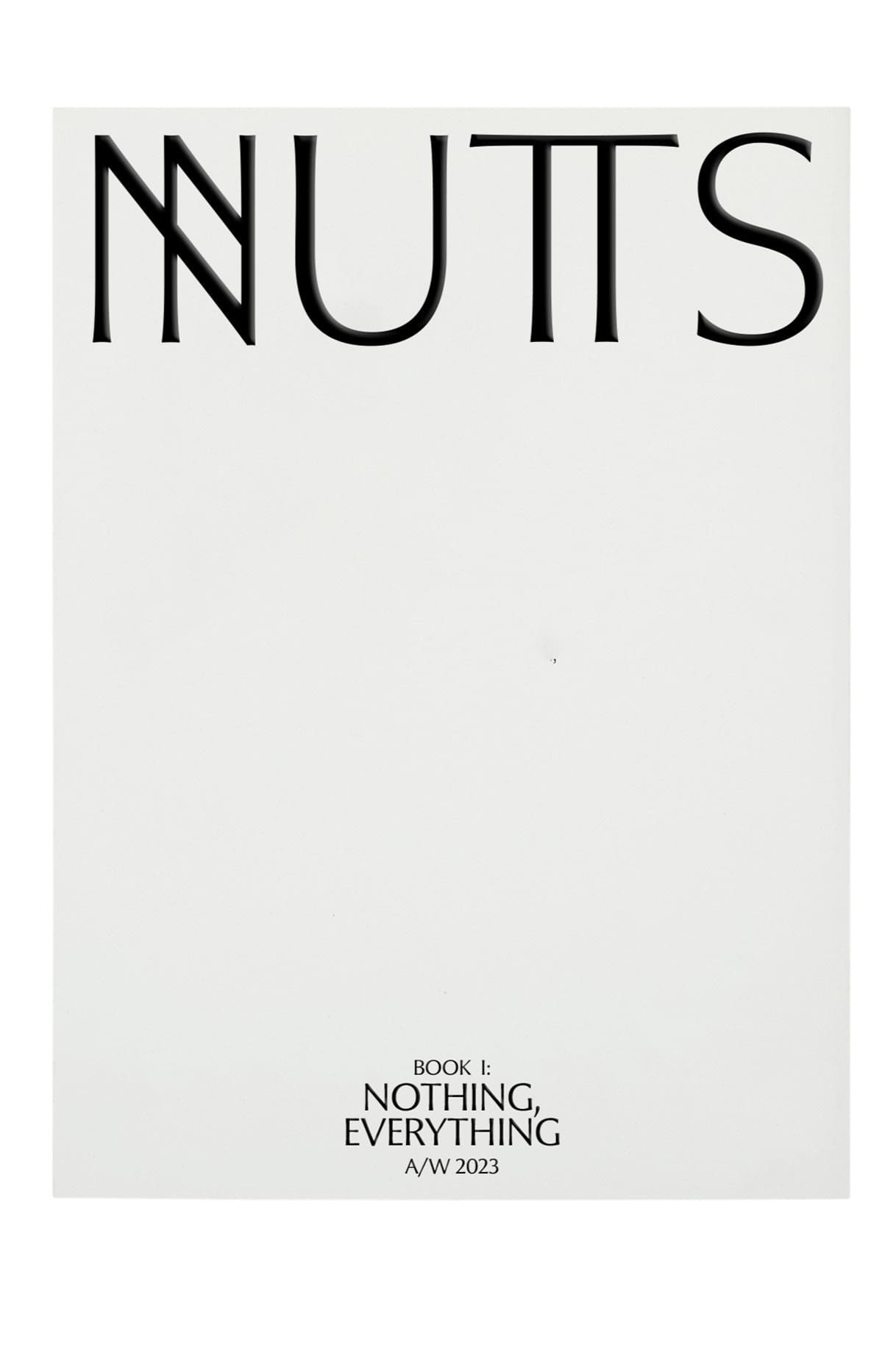

If someone asked you to “pass the nuts” (meaning this magazine), you’d need two hands to do so. Though composed of light, non-glossy paper, Nuts is the size of a small phone book. That particular relic of the past wasn’t cited as a reference, but self-help books from the ’60s, vintage Japanese photography magazines, and the idea of zines were all in the mix as the project came together. “You kind of create worlds when you make magazines,” said Turley.

He should know. By day Turley works as the editorial/design director of Interview magazine. In 2018, he cofounded Civilization, “a newspaper about New York City,” and he also launched the creative agency Food. Now Turley has teamed up with a group that includes writer and brand whisperer Natasha Stagg (whose next book is soon to be published) and artist and stylist Bunny Lampert to launch an anti-fashion—or, more accurately, anti–fashion system—magazine.

When I met Turley and Lampert on a rainy evening, the former was at first reluctant to categorize Nuts as a fashion magazine; hybridizations are more his thing, while Lampert had no doubts that it is just that. “It all started with how we feel about the clothes and what’s going on with the clothes; that’s why it’s a fashion magazine,” Lampert stated. “For me, the clothes we see in pictures have this distance, but then as soon as we buy them, they change their meaning,” said Turley. “I’m personally interested in that relationship that you have with your own clothes, as opposed to some clothes that got brought in on a rack.”

In a separate conversation, Stagg said: “There are exciting things happening in fashion, but it feels like it’s not so much the clothes that are the exciting part. And that’s what I was thinking about when Richard was like, ‘What would a modern fashion magazine look like?’ There doesn’t need to be anymore fashion—obviously there should be less—but if you’re going to make a magazine, what should it try to communicate? There’s this thing about what people wear when it looks like they don’t know anything about fashion; that’s maybe most interesting to people these days.”

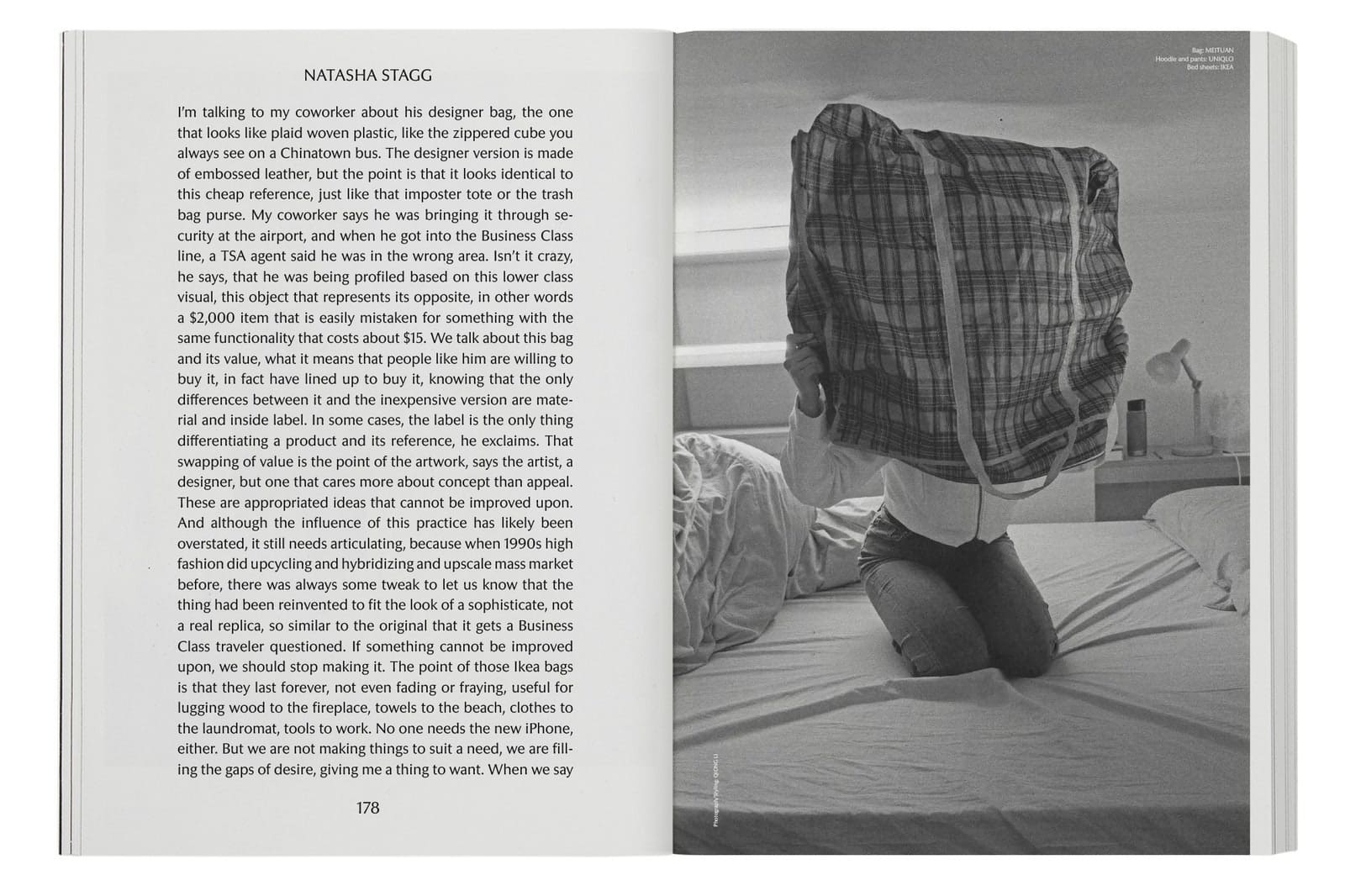

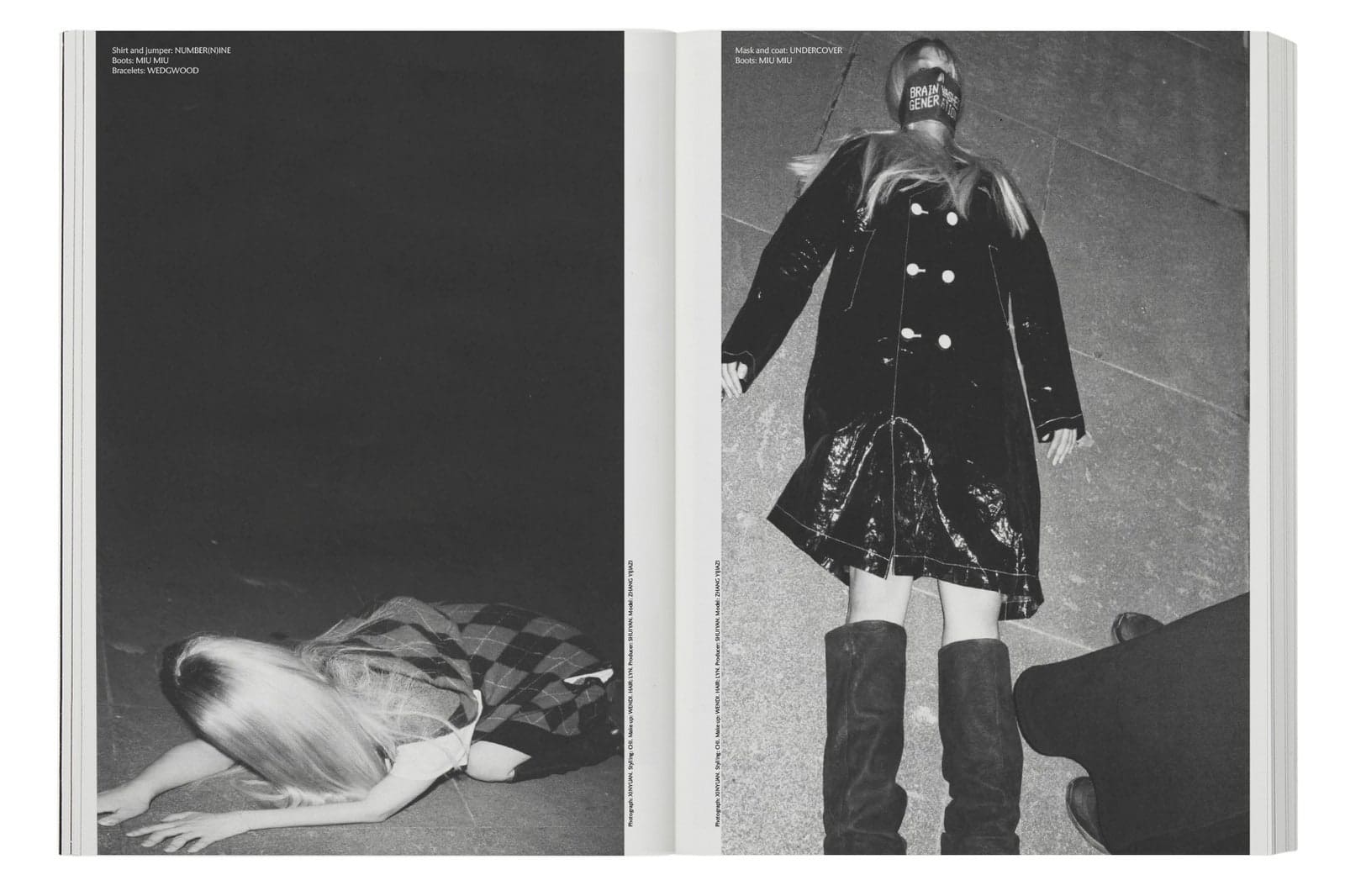

A lot of care was taken so that production did not follow standard fashion-industry practices. Next to none of the contributors are fashion photographers, for example, and apart from one series of photos taken in a store dressing room (see the back cover, above), nothing is borrowed. There is no advertising. One might say that Nuts is not about big-F Fashion but little f: real clothes, real people. Yet despite a geographically diverse list of contributors, the aesthetic is strangely static—arty and grungy are adjectives that to come to mind. Nuts seems focused on a creative class whose day jobs don’t always allow the full expression of their vision. The focus on the “normal”—clothes that (for the most part) don’t have luxury labels—can suggest another relationship to class (high versus low), but Stagg suggests there’s a connection between the accessible American Apparel vibe of Vice in the aughts and the kind of clothing featured in Nuts. “Of course there’s a fine line between fetishizing the low end of fashion and just looking at what people generally wear,” she said. “It’s easier to say what our magazine is not than what it is looking for. We’re not researching so much; it’s more intuitive.”

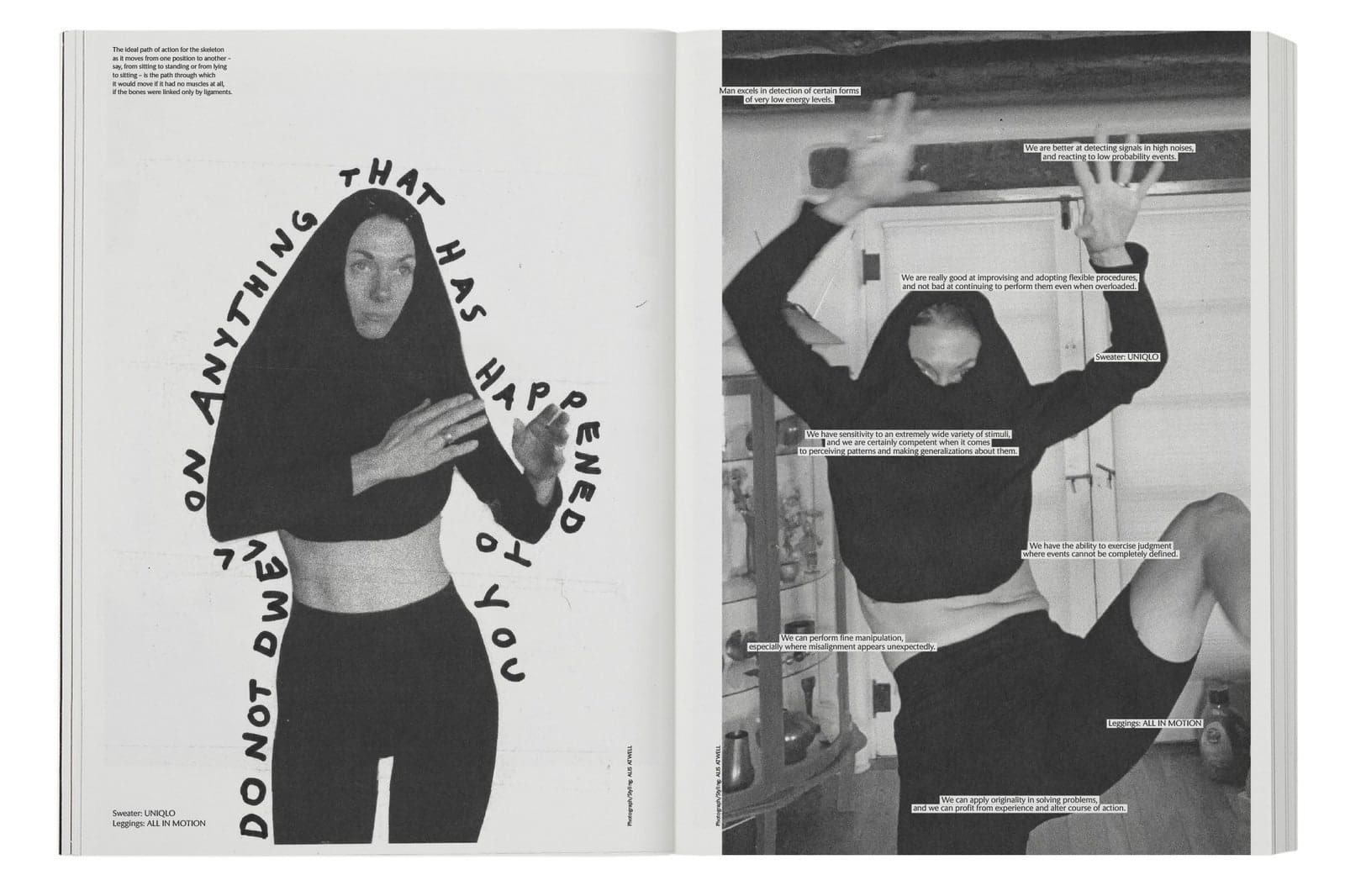

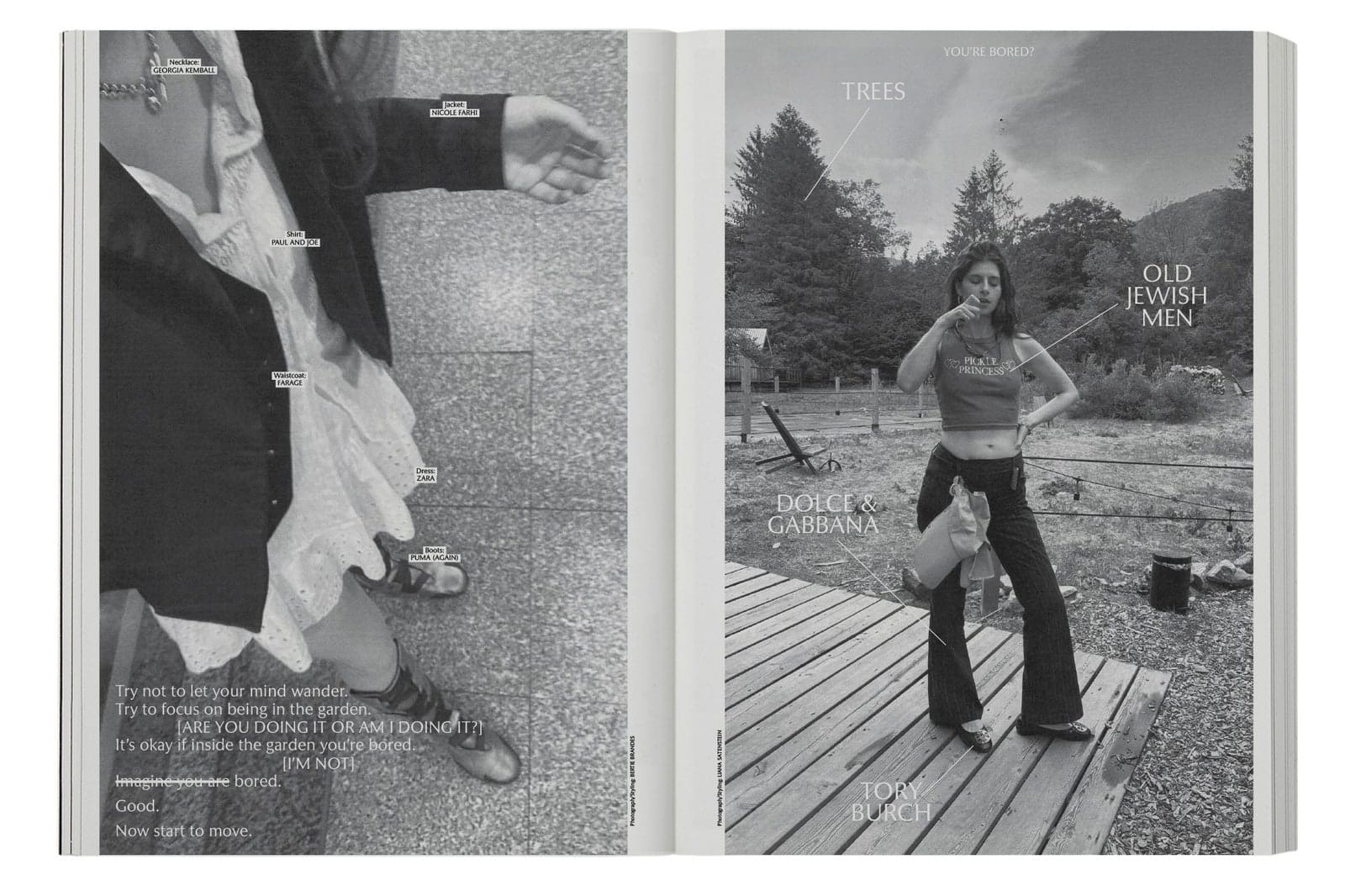

This publication reshuffles ideas of what a magazine is in both conceptual and physical ways. Mainstream clothes are in; standard industry practice is out. Images and stories, including Stagg’s very New York chronicles, are broken up and distributed throughout the entire issue. Bertie Brandes and Isabella Rae were responsible for what Turley calls the magazine’s script, which is littered with mantras and calls to action. And all of the images were manipulated: Everything was printed out and scanned, rather than being used directly in its digital form. This, combined with the chalky texture of the paper and the choice to publish everything in black and white, gives Nuts a physicality that’s not unlike a well-worn pair of jeans, not pre-aged but broken in by wear over time.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Nuts is the graphic design. There is text in corners as is standard magazine practice, but there is also text over and around photos, which is a point of difference that has a mixed-media effect.

Like a shell contains a nut, so Nuts hold contradictions. The first is on the cover, which is time stamped A/W 2023, which seems a bit ironic seeing that for the most part the clothing in the magazine was pulled from personal wardrobes and thus largely out of time—and out of (commercial) circulation. Plus Nuts exists in opposition to traditional fashion magazines, and as a result, for insiders, there’s something of a reverse Where’s Waldo? aspect to it. The takeaway? Seek and you shall find style that exists outside the boundaries drawn by the industry.

Below are snippets from conversations with Turley, Stagg, and Lampert on authenticity, rebellion, and what people really wear.

Vogue: What was the genesis of the magazine?

Richard Turley: There wasn’t a ton of really considered ideas going into it, but one of them was just the way that clothes make us feel, and how clothes choose us, which is sort of an inversion of what [we are usually told]. Fashion advertising and imagery comes from this very top-down place, and we were interested in understanding it from the bottom up, but not just seeing that as street photography, [rather] the way that a piece of clothing changes its meaning when you put it on, and the story that it has built into it becomes your own story. It’s a way of talking about how clothes make us feel.

Bunny Lampert: A thread throughout the magazine is this “feel” thing. Most of the shoots in the magazine aren’t styled by people pulling clothes from a showroom, it’s what people already own or what they’ve made or have access to. If people are already wearing these clothes, they’re not just for trying on for a photo and then returning. They felt something about it, purchased it, wore it, and now are being photographed in it.

Natasha Stagg: I think everybody knows something about fashion now, especially in New York. You look around and you’re like, Okay, that person’s wearing what looks like absolute trash, but probably if you ask them, they would say what season it was or that it’s a reference to something specific. So there’s this way of hitting some sweet spot of intentionality and something that looks unintentional.

Is it fair to say Nuts is about community?

Stagg: I think all of us work in fashion in some capacity. I work for brands doing copywriting, and I have worked for magazines, the frustration with those jobs being that they’re selling a product no matter what. What if I could do a side project with my friends and that involved more and more friends that maybe have the exact same frustrations? Maybe it would just give us some relief from our day jobs and then hopefully it will get us more day jobs, because really, in the end, we all need money, and I think we are interested in the money aspect of it. We’re interested in what people actually wear; that kept on coming up and we were like: Okay, fashion magazines exist as aspirational objects, but are there fashion magazines that combine the aspiration with the more accessible?

Lampert: Nuts creates a community. It makes everyone in there related visually. They’ve never met each other, they never will. And they’re from all over the place; they all use different cameras. [This method] makes it feel like: Okay, we’re all here together, this quality has now been set. I see it as the ’60s kind of aesthetic; it’s like a hippie magazine, but it’s not hippie, it is fashion. I’ve been making my own photo shoots since I was a kid. We made fashion editorials—we didn’t know it—but we really liked clothes and we liked dressing up and performing. And we do that as adults with our friends. [The kinds of shoots in Nuts] are, in my opinion, already happening, but there’s not necessarily a place for them in this industry because it’s all about people at the top and the regurgitation of the same models. But there are a lot of people who are really inspiring, [and] this is what they’re doing at home and this is what they’re doing with their friends. It’s an opportunity to take someone who looks great or has great style or has great clothes and do something, put it in print, because a picture of someone with great style on the street getting interviewed about what they’re wearing at that moment is really boring now for us. But what would they do if they had 10, 15 pages in a magazine? They’re going to do something way more interesting than just how they look at that moment.

The format is unusual; the pages aren’t glossy and there are only black-and-white images, and there’s a good deal of graphic design.

Turley: I wanted Nuts to be a confusing object. It’s not quite a book and it’s not quite a magazine, and it’s not really about fashion and it’s not really about clothes. I’m interested in the middle ground. So I wanted to make something big that’s light. Magazines are objects, right? They have a presence in the world. I just wanted to think about that from a different perspective and I wanted it to feel different. I wanted it to smile, I wanted it to be kind.

One of the things that we bonded over was to think about making images differently, and to think about the production of those images was really important, to just try to do something new. I don’t know how new it is, or if it’s really even possible to do anything new, but I think you’ve got to try. And I think just in terms of the language and the words and the interactions, I think that helps the communication. The words help pictures, they drive pictures, they frame them, they reframe them. Words allow pictures.

In my world, words and pictures are one and the same. The words and where they are positioned is how you can affect meaning and create a different feel, and we were interested in a mood. I hope that the magazine feels like a mood.

So how is it different from a zine?

Turley: I think the production values are different. I wanted it to feel like a zine in a sense, or to have a feel or take cues from those things. There is a little bit of cut and paste in there, there’s a little bit of collage. Every single page has been printed out and scanned in again in an effort to make it feel different. If you just use JPEGs or images that come straight through digitally, they have a certain feel to them. But old magazines and Japanese photography magazines were very important as a resource because they’re so beautiful. The reason they’re so beautiful is that [the images] have come down two or three generations. It’s a piece of film that’s being printed out and scanned in again. I think that every time you take it down a generation, its meaning changes a little bit. It’s a very subtle thing. I think that there is this kind of intentionality behind so many things we do. I think the objects have meaning; I think objects have a certain power and a certain weight to them. The fact that everything in the magazine existed in a previous form and was touched by hands, manipulated, put into a sequence, and was scanned back in again—maybe I’m just a bit idealistic or a bit spiritual—but I think it makes a difference. I think that kind of intentionality at that level creates something a bit different.

So were people given assignments? How did it work?

Turley: Nothing was really commissioned as a story. We talked to the people who we were interested in working with and explained the concept and just let them go.

Stagg: When I talked to a few different stylists about what they would want to contribute, I just kept saying, “What have you been told you can’t do at a magazine so far?” They had a lot of ideas, [those] in the back of their head already. They’ve probably pitched these ideas somewhere and then that magazine was like, “Oh, there are no brands that are advertisers. There are no models who are from the agency we work with.” There’s always this conversation about what that story does for the magazine. And Nuts is just like a brand-new magazine, so we have no expectations.

I was struck by a kind of commonality of style aesthetic.

Turley: There’s a little bit of New York and there’s a little bit of L.A. and there’s a little bit of London, but there’s a lot of China, there’s a lot of Colombia, there’s lots of Iran in there, there’s a lot more of rural America than I think you see in traditional magazines. It was this idea of broadening the lens a bit in terms of imagery and where people normally look to for clothing pictures.

One of the things that we found is that everyone dresses the same all over the world. Which may be disappointing, but in some ways I found it quite reassuring, because we all just want a common language.

Lampert: I think there are tons of different aesthetics that happen naturally. No one’s trying to front, [they are photographed in] what they’re already wearing or what they want to be photographed in. A lot of people are like, “I want to hide, I just want to be comfortable. I like fashion, [but] how we look doesn’t really matter.” But then we do look a certain way. Nuts [captures] something that’s naturally occurring, set up to be photographed.

Do you think if this idea of big-F versus little-f fashion were applied to Nuts, it would be about the latter?

Stagg: Definitely. The only story I think in this issue that has some big-F Fashion in it is a girl in a dressing room at some store. It’s not borrowed from the showrooms, and I think that was the idea; it was like, this is what you can try on at the store right now.

But is it really accessible? You can’t really get the look if it’s from someone’s closet.

Stagg: I like the idea of it not being about what you can purchase. I guess that’s not sustainable. If the magazine needs to sustain itself, it needs to have ads, and I don’t know if it will.

I think back to when I was reading magazines as a teen, and I remember seeing “what this person does with their day” kind of stories: I was so enamored with that. I was like: Okay, so Sofia Coppola, the coolest person ever, goes to this sandwich place and goes to this record store and wears these clothes. And back then also, I saved some Seventeen magazines from when I was a kid. And [celebrities] used to wear Old Navy. They weren’t going to Celine, they were shopping at the mall as a realistic version of their day. That was what celebrities used to do. And we forget that because they’ve all become walking advertisements for brands, and those brands are not Old Navy. And so I think I just got really disheartened when there was this moment where influencers could have brought back that idea of just showing a real person doing real things every day. And if they’re cool enough to someone, then they would help that person be excited about life. But immediately, if that person gains numbers, then they get sent garments and they get sent products. Even the food that they eat is not really the food that they would choose to eat. So it’s just this weird feeling of nothing can ever be authentic again, because there’s always the prospect of getting money.

Something I’m interested in is that there’s so much to explore. People are still wearing interesting things, and maybe the most interesting things now are outside of that expected street-style photo because, eventually, especially during fashion weeks, people started dressing for that and trying to get more attention with giant red boots or whatever. It’s like everybody’s wearing a balloon hat now when they go to a fashion show.

These interviews have been condensed and edited for clarity.

This article was originally published on Vogue.com.