Photograph by Eric Mueller, courtesy Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Opposite: L.A. Liberty, 1992, acrylic, cotton yarn, plastic buttons, mirror, gold thread, painted cloth on stitched and padded canvas. Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

Photograph by Eric Mueller, courtesy Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Opposite: L.A. Liberty, 1992, acrylic, cotton yarn, plastic buttons, mirror, gold thread, painted cloth on stitched and padded canvas. Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

Pio Abad reflects on the exuberant work of his aunt, the Batanes-born, world-traveling artist Pacita Abad, whose immense retrospective blazes its way across North America.

In a 1991 interview for Wild at Art, a short film produced by PBS-TV to celebrate her major commission for the Washington D.C. Metro, Pacita Abad was asked what she has contributed to the United States as an artist. “Color,” she proclaims boldly. “I have given it color.”

Pacita’s words saturated the galleries of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis for the opening of her first ever touring retrospective—the largest ever museum exhibition in the United States devoted to not just a Filipino artist, but to an Asian American female artist. The exhibition opened on April 14 and runs until September 3, before traveling to San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in October, and MoMA PS1 New York and the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto next year.

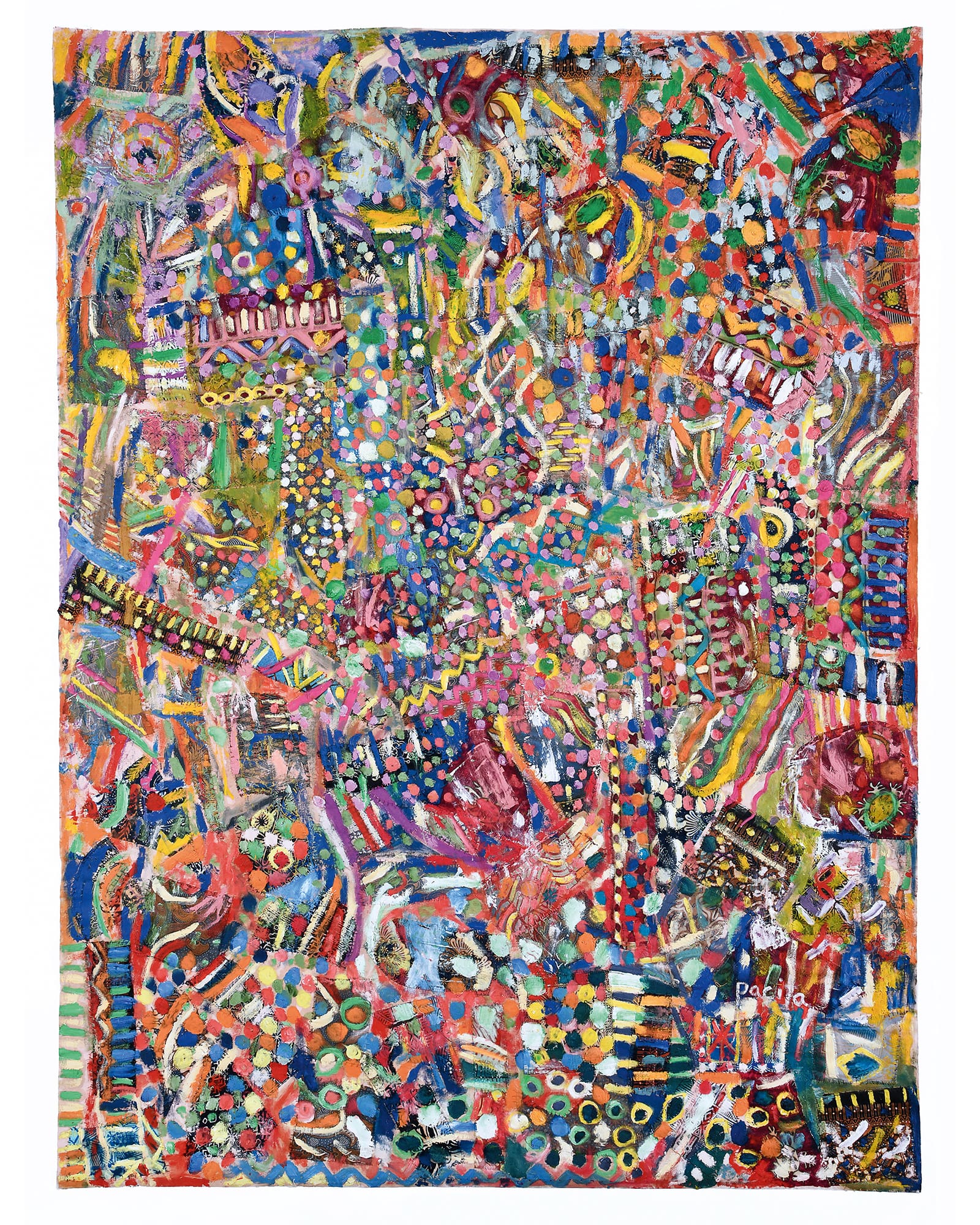

The austere white spaces of the museum were transformed into a multi-hued environment. The staircase leading up to the exhibition was swathed with the frenetic golden yellow polka dots of her 2002 painting “I Have One Million Things to Say,” the walls of the galleries rendered in blush pinks, warm yellows and greens, and deep berry reds. The retrospective, thoughtfully curated by Victoria Sung with the assistance of Matthew Villar Miranda, brings together over a hundred artworks produced over a breathtakingly prolific 32-year artistic career that saw her live in over 60 countries across six continents, making more than 5,000 works in the process. Pacita is best known for her “trapuntos,” a term she coined for her large-scale paintings on unstretched canvas that were quilted, embroidered, and embellished with assorted materials. Her trapuntos not only showcased her skills as a material omnivore, but also incorporated the techniques that she learned from the different communities she encountered throughout her travels: Rajasthani mirror embroidery, Papuan cowrie shell ornamentation, Korean ink brush painting, and Indonesian batik, among others.

The series “Six Masks from Six Continents,” initially commissioned by the Washington D.C. Metro and installed in the cavernous hall of the central train station of the nation’s capital from 1990 to 1993, is reunited at the Walker for the first time in three decades. The work celebrates the growing diversity of the United States, commemorating the demographic shifts in the country through Pacita’s colorful lenses and drawing inspiration from ceremonial masks from around the world. The writer Murtaza Vali poignantly refers to them in a recent Artforum magazine feature as “icons of global indigeneity.”

“L.A. Liberty,” her bold reimagining of the American monument as a woman of color clad in bejeweled patchwork robes, is shown alongside the rest of her “Immigrant Experience” trapuntos, depicting the struggles of immigrants of color: from fellow artists and Korean grocers to Bangladeshi restaurant workers and Cambodian refugees. In “I Thought the Streets were Paved with Gold,” Filipino cannery workers in Alaska share the same pictorial space with nurses, Dominican house painters and New York street vendors. What shines through in Abad’s depictions of migrant lives is a strong sense of empathy and solidarity with those in the margins of society, whose stories intersected with hers.

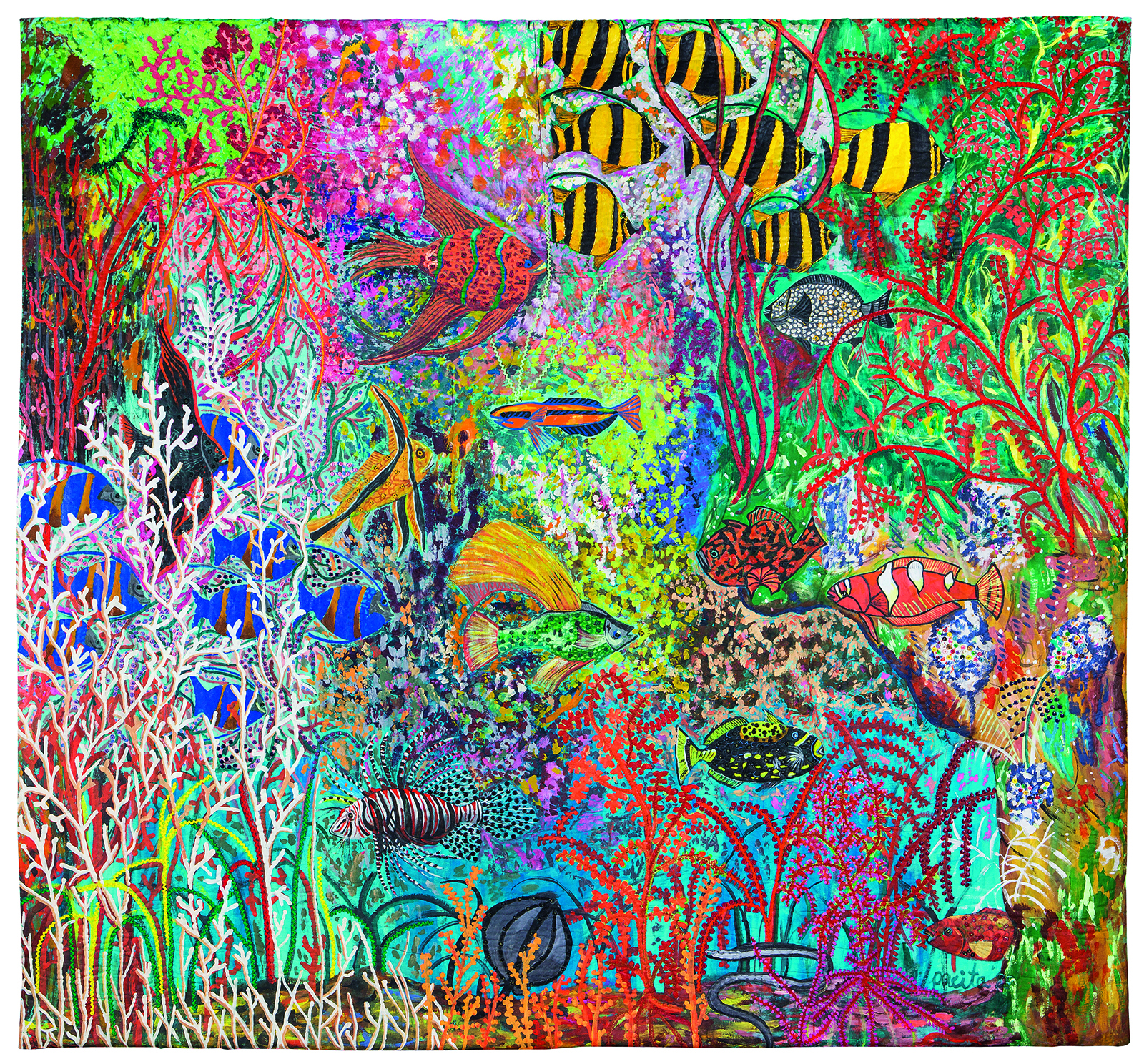

The final room in the exhibition transforms the cathedral-like Herzon and Meuron designed space into an underwater Philippine paradise, taking the viewer through a journey of the country’s coral reefs in Puerto Galera, Dumaguete, and Apo Island with an overwhelming profusion of canvas, ribbons, buttons, glitter and paint. Produced during the politically tumultuous period during and immediately after the fall of the Marcos dictatorship, Pacita’s underwater wilderness suggest both her need to rediscover her place of birth after years of being away and her insistence on finding beauty underneath its turbulent surface.

Over a thousand five hundred people attended the opening, heeding the museum’s invitation to come dressed in their brightest and most patterned attire. With the unseasonably warm spring weather in Minneapolis, it was as though Pacita had brought the tropics to the American midwest.

Amid the joyous occasion, I had pangs of bittersweetness wishing that Pacita herself could have been present to witness this epic celebration of her art and her life. Many of my childhood memories centered on Pacita’s exhibition openings in Manila. She had already perfected her peripatetic existence from the time I could remember, but her arrival in Manila was an annual highlight in the family calendar. I have vivid recollections of the flamboyant clothes that she wore and how she held court, a one-woman circus electrifying the town. Her distinct cackle, captivating and terrifying us, her nephews and nieces, in equal measure.

At the 1986 opening of her exhibition at the Ayala Museum, where she transformed a museum into an underwater environment for the first time, she arrived wearing a full scuba diving outfit complete with flippers and an oxygen tank. After the ribbon cutting ceremony that traditionally marked her openings, the massive raffia and satin ribbons would be reconfigured as part of her already outrageous outfits. I have distinct memories of Pacita clad in an Issey Miyake dress with a hand-painted depiction of an amorous and fully nude couple, first worn at an opening in SM Megamall and subsequently to a walk down the aisle as godmother at a cousin’s Catholic wedding.

At her last exhibition opening at the Cultural Center of the Philippines in August 2004, when cancer had already taken its toll on her body, she wore a crown of flowers and her wheelchair was equally garlanded. That month was the last time I was able to spend with her as I moved to Glasgow to go to art school a few weeks after her opening, following her advice that if I wanted to be an artist, I had to get the f**k out of Manila and see the world. She passed away in December that year.

The two decades I’ve spent living in the UK and navigating the art world have been fruitful not just in articulating my own artistic worldview and building a supportive and equally itinerant community, but also in finding a way to introduce Pacita’s work to the world, years after her passing.

In 2016, I was invited by curator Joselina Cruz to co-organize an exhibition of Pacita’s work at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MCAD) Manila, her first major exhibition since her passing. “Pacita Abad: A Million Things to Say” at MCAD Manila would later open to great acclaim in April 2018 and mark the start of my journey as a custodian of her artistic legacy. In preparing for the exhibition, Joselina and I found ourselves one wintry November week in Washington D.C., unrolling Pacita’s trapuntos for the first time in nearly two decades. Most pieces from her five thousand-work oeuvre had been carefully stored and archived by Jack Garrity, her devoted partner and fellow traveler for 32 years, who, along with his wife Kristi, had unshakeable faith that a new generation of artists, curators and scholars would breathe new life and interpretation to Pacita’s work. After many years in hibernation, the colors had not lost any of their vibrancy and the layers of material and processes within each painting continued to astound. If anything, the works had gained the resonance of time, accruing the weight of witnessing their depicted histories being repeated.

One of the pleasures of introducing Pacita Abad’s art to a new audience has been watching them encounter her work for the first time. They enter the gallery mouth agape, overwhelmed by the scale of her paintings, and drawn to the luminous intensity of her colors and the intricate riot of printed textiles, buttons, seashells, ribbons, the occasional piece of jewelry and even the odd pair of denim jeans that adorn each surface. As they look closer, there is an additional moment of wonder as their eyes travel through the hand-stitching that covers every inch of her monumental canvasses. Some prefer to sit in front of her works as though they were watching a film, mesmerized by every stitch, every brushstroke and every sequin. As a guest at the Walker opening said: “I didn’t know Pacita Abad’s work existed a year ago and now I cannot imagine my consciousness without it.”

As an artist, my work is deeply committed to chronicling my family’s story, weaving their struggles and journeys into the fabric of socio-political histories. As the curator of Pacita’s estate, it has been an extraordinary privilege and an immense responsibility to introduce her work to new audiences and assert her significance in constructing a more global history of art, one that addresses its failings in embracing the experiences of women and people of color. Pacita’s incredible body of work reimagines the art historical canon into a much more complex and compelling narrative that is fabulously experimental, fearlessly inclusive, and vibrantly political.