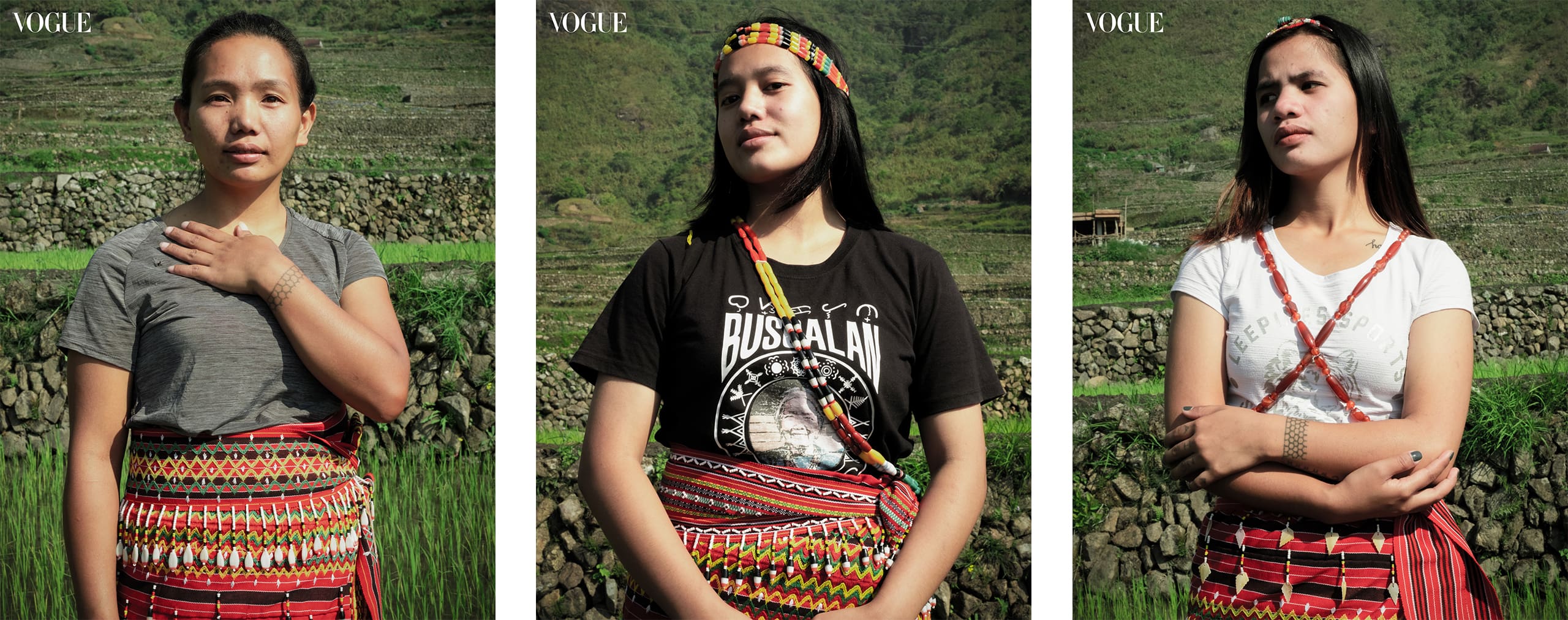

Apo Whang-Od with grand-niece Grace Palicas, who has inherited her commitment to the craft of batok. Photo by Artu Nepomuceno

Under Apo Whang-Od’s wing, the young stick-and-thorn tattooers are not only preserving, but redefining a thousand-year-old tradition.

High up in the Cordillera mountains of the Philippines, within the Kalinga region, sits Buscalan. The remote village is home to the famed mambabatok and oldest living tattoo artist in the world, the centenarian Apo Whang-Od.

She has found herself in a cultural duality. As a keeper of tradition, the artist has kept a tradition with over a thousand years of history alive, ensuring that parts of our origins live on for future generations to witness. On the other hand, because of her, the sleepy community which remained independent and untouched even through several hundred years of colonial rule has seen rapid modernization and an influx of tourism in the past decade alone.

Grace Palicas, Apo Whang-Od’s grand-niece, is often heralded as the next generation of mambabatok. What many don’t know is that there are now dozens, if not hundreds, of young apprentices keen on learning and continuing the practice.

“Yung word kasi na ‘the last tattoo woman’ sa generation niya,” Palicas tells Vogue Philippines. “Pero marami din na tulad ko na bagong henerasyon. Marami din na gumagalap na pagpatuloy na pagpa-tattoo para hindi mawala.” [The term last tattoo woman refers to her generation. But there are now so many like me. A whole new generation is gathering to continue the tradition of tattoing so that it doesn’t disappear.]

In an interview with Vogue Philippines, Aiza Ayangao, one of the young mambabatoks under Apo Whang-Od’s wing, tells us that the revival of the art has been a huge help in many ways. “Para sa amin, parang naging scholar na kami ni Apo Whang-Od. Malaking tulong na yung pagbabatok sa amin. Kasi natutulungan yung sarili namin, pamilya, tsaka yung financial,” she says. [For us, it’s like we’ve become scholars of Apo Whang-Od. Tattooing is such a huge help to us. It’s helped us, our families, and our finances.]

Ayangao has been working on the traditional art form for nearly a decade, having started in her mid-teens. Alongside her is Chessy Ambatang, who likewise has just over a decade of experience, and started learning how to tattoo using stick and thorn at just nine years old. “Ano din, karangalan kasi sumikat yung lugar namin. Pag sinabi namin taga Buscalan kami parang ‘Ah, kay Apo Whang Od yun.’ May respect sila kung san kami galing,” Ambatang explains. [It’s also an honor, because our area became popular. When we say we’re from Buscalan, people are like ‘Ah, that’s Apo Whang-Od’s.’ They have respect for where we came from.]

Renalyn P. Koda-Ol, another apprentice, took up the practice after seeing Apo Whang-Od and her two grand nieces, Palicas and Elyang Wigan, struggle to accommodate the thousands of tourists interested in getting tattooed. “I was 18 years old,” Koda-Ol describes of her start. “I just watched and learned from my mother… and then after two weeks, I did tattoos [for] a local tourist.”

With discussions on decolonizing beauty becoming exigent across industries, you need not look further than our own roots to find traditions that seem radical among commonly held beliefs to this day. We’re all likely aware of commonly held beliefs with Western origins, which dictate that tattoos are reserved for delinquents, criminals, and the like. For indigenous communities, particularly ones like the Butbut people in Buscalan, tattoos symbolize strength and beauty.

According to these young mambabatok, the explosion of the tradition’s popularity has reshaped not only their lives but has also brought the practice into the modern day. Before Whang-Od, master tattooers were predominantly male. These days, according to Ayangao and Ambatang, there are more women than men mambabatok.

Even the meaning of the tattoos has evolved over recent years. Like their ancestors, the village elders still subscribed to the tattoo’s original meanings. “Noon kasi, yung tattoo sa lalaki, pag warrior ka. Tapos pag babae, maganda,” Ambatang says. [Before, tattoos on men meant that you were a warrior. And tattoos on women meant that you were beautiful.]

Ayangao tells us that these values are slowly evolving with the times. “Naging art na siya. Pero sa mga elders, parang ganun din yung ibig sabihin sa kanila. Maganda ka kung marami kang tattoo, meron kang pinatay kung sa lalaki.” [It’s now become an art form. But the elders still hold on to these meanings. As a woman, you’re beautiful if you have many tattoos. As a man, tattoos mean you have killed.]

Thanks to Apo Whang-Od, a once-dying art now sees a new generation of aspiring artists, proving that perhaps sometimes, for the past to live on, it must evolve.

Producer: Anz Hizon. Production Assistants: Jojo Abrigo, Marga Magalong, Renee De Guzman. Photographer’s Assistants: Aaron Carlos, Choi Narciso, Sela Gonzales. Special thanks to the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples.

Get your copy at shop.vogue.ph