Photographs by JL Javier

The photographer just had his first solo exhibition with Tarzeer Pictures.

One must break convention, even a little. We’ll start with his name.

In lieu of referring to the artist by his last name, to call him Renzo, just Renzo, just today, closes the gap.

Is it good? He asks, on the way to his own show walk-through.

I’ll tell you when you’re here. There’s no way to pass judgment on a body of work such as this. Its aesthetic merits (painterly yet photographic, digital yet tactile) are to its own beholder. Toponder on its larger conversations seems is to miss the point: the photography show Who Needs A Blade? in its back and forth on self-harm and self-preservation, proceeds with a gentle yet urgent tension, constantly on the brink of finding peace and of pushing one’s self over the edge.

It is, as in Renzo Navarro’s own notes, a rejection of the world by refusing to photograph as things appear in real life, while maintaining that this abstraction is not a deviation from the natural world. It’s a mode of honesty.

“My sister said the show’s name should be, ‘Why Not Scissors?’” Renzo shares, in humorous deadpan. He’s staring at the title of his own solo show, printed out in bold black on the Tarzeer Pictures gallery wall.

Asking why not is correct. Scissors, or some other such instrument, indicates dexterity and sterility in the handling of emotional complexity. The photographer Renzo Navarro has lensed many types of images, some less biographical than others. His images have been on billboards, on magazine pages (including Vogue Philippines), and on social media feeds.

“Seeing his commercial work online back then, we were struck by his deliberate use of lighting and his ability to mold images in post production to fit his imagination,” Tarzeer Pictures executive producer and co-founder Dinesh Mohnani shares, tracking the growth of Renzo’s signature thematic of “sabotaged” utilitarian objects and a painterly quality in digital imagery through tarpaulin-sized single pieces to triptypchs on a wall. This includes a special Tarzeer Pictures presentation at the Makati flagship of the acclaimed Silverlens Gallery.

That is to say, Renzo’s more artistic forays into photography are less a technical question of creation. Here, in this show, Renzo worked with his hands. Who needs a blade, when the undertaking in itself was enough? Who needs a blade, when a lens can be just as sharp?

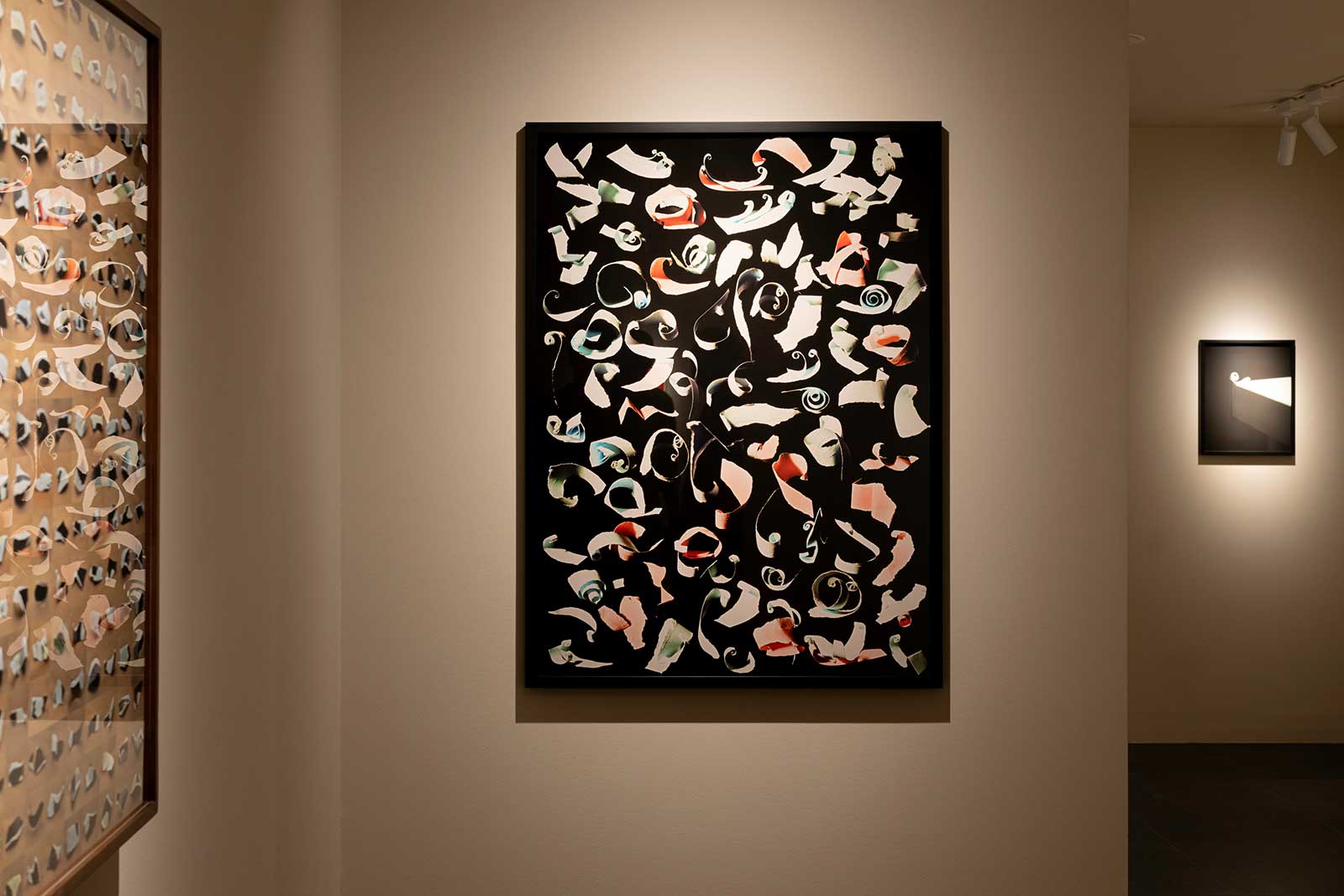

Here, at Tarzeer Pictures, the 17-piece solo show features Renzo’s work with paper, in both the overt sense and in a more reflective manner. That is, he ripped apart pieces of paper—he loves me, he loves me not, or something hopeful like that, the artist narrates in his personal notes—photographed and printed them out archival pigment paper, ripped those prints, and repeat. The final work finds some encased in museum glass that dull the reflections of gallery lights, of another print across the room, or of a passing body. Other pieces do the exact opposite, reflecting the piece, or the one after that, or the one after that. A photo within a photo, a print within a print, layered gently within each other like caramel chiffon cake.

Renzo is careful about these subtle details of reflections, in particular because of how they embody his own self-hate and self-preservation. The curator and Tarzeer Pictures co-founder Gio Panlilio points to two pieces of work that bookend Renzo’s show as the very ones that define it, because “they are, in effect, the same shot.” “Did I Leave Enough Breadcrumbs?” starts the show at the very front in stark monochrome, a single coiled piece of ripped paper literally at world’s edge; “Hierarchy of Needs” ends the journey, rotated to appear at the end of the road, at a gateway of bursting color. “Each one,” Panlilio explains of what he sees, “holding within it the potential of the other.”

Of these two pieces, Renzo writes, in a private message, “I thought it was an important detail that they’re not visible to each other while coexisting in the same space.” The parallelism to how these concepts also co-exist within the self is verbalized by the show itself.

Everything, it seems, revolves around these reflections and paradoxes of the I. This show is not about me, this article is not about you. But the I of this show makes it okay if it were also about me, about you, about anyone who has ever had unwieldy, overwhelming thoughts primed for catharsis. The public I supposes identity and vulnerability, but forgets the suffocating circle of adjacent emotions that interplay the interior I and the public eye. Are interior thoughts able to undergo scrutiny of the art world? What can we say about someone else’s loneliness? Can photography become biographical for the person behind the lens, can this biography become intimate?

“I don’t have much experience with intimacy as a two way street, and so it’s easy for me to treat photography as a wall or glass curtain where I can hide behind and observe the world as it is. But because of this I’m able to find comfort in being vulnerable without consequence,” Renzo writes. “The process is for me, but the work is for the viewer. I’m able to give without asking for anything in return. I think generosity is an important ingredient to intimacy.”

Who needs a blade, when one’s own hands can already do so much of that work? I’ll tell you when you’re there.