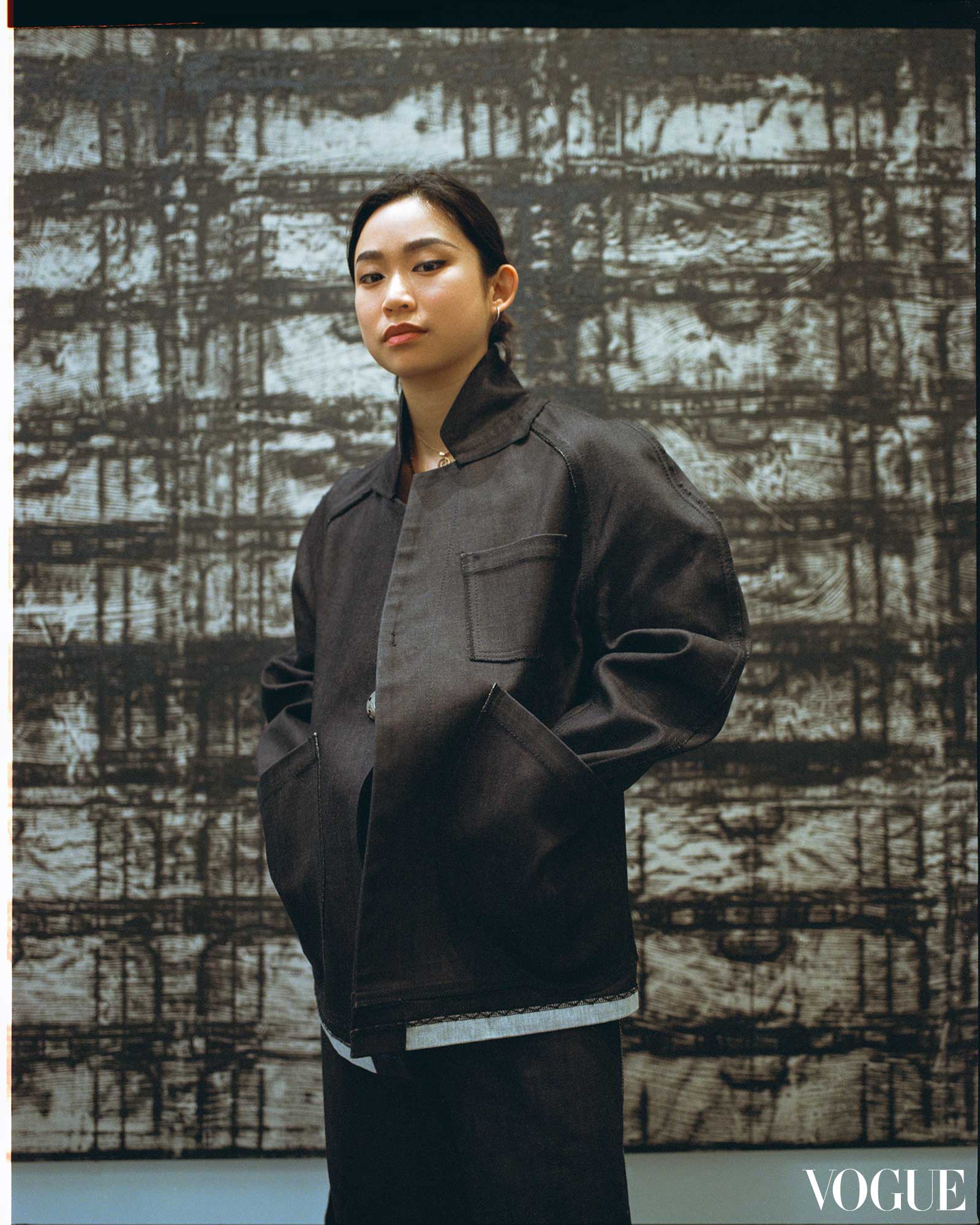

Photo by Junell Tanio

To observe artist Nicole Coson’s most recent exhibition at Silverlens New York called “In Passing” is to contemplate displacement and diaspora by asking: what is brought with, carried, lost, or shipped to a home?

Sunlight filters through the high windows of a printmaking studio in East London, casting a soft light on London-based Filipino artist Nicole Coson. On her right stands an old etching press. The monolithic machine, manufactured to withstand the pressures exerted while printing Intaglio, flanks the frame of the photograph, its imposing cast-iron structure partially veiled from view. The space feels hushed, the press a silent counterpoint to the delicate works around it.

From her arrival in London at the age of 17 to pursue a Fine Art degree at Central Saint Martins, to the subsequent completion of her MFA in Painting at the Royal College of Art in 2018, printmaking techniques have evolved into an intimate part of Coson’s artistic practice. For her, this process carries a poignant sense of completion and loss — each pass through the etching press becomes a fleeting moment, “an instance never to occur again.”

This ephemerality mirrors her approach to art: Coson fractures form, giving way to a dance of ambiguities. Her work, as she describes, navigates the interstitial spaces “between the organic and mechanical, anonymous and personal, a specific place and anywhere at all.” This act of unraveling meanings has been central to her art practice for years, exposing the illusions we superimpose upon the familiar. Her chosen medium of monotype printmaking mirrors this impulse for reinterpretation and reconfiguration: each impression created is a temporary representation, a soft, loose copy of its source.

In her past shows, Coson has explored the deconstruction of everyday objects — camouflage patterns and window blinds — visual signifiers of obfuscation and the regulation of visibility. Monumental monotype prints transform these objects into artifacts that expose the tenuous relationship between the real, the perceived, and the reproduced.

This ongoing fascination finds new expression in her most recent exhibition, “In Passing” at Silverlens New York. Here, she turns to the fruit and vegetable crate, and transforms it into a realm of textures and traces. Eight oil paintings, none of them titled, dissect its visual vocabulary: stacks of crates, once sturdy and utilitarian, dissolve into textured abstractions, while individual crates, isolated on the canvas, expose grid-like structures that almost seem poised for dissolution.

Coson employs various printmaking techniques to trace the crate’s battered surface, transferring its subtle degradations onto linen. This lends a tactile intimacy to her work: linen, a fabric woven from natural fibers, has subtle imperfections — slubs in the weave, variations and inconsistencies in its weight and texture — that mirror time-worn crates.

The installation, “Some place, within here,” confronts us with aluminum-cast oyster shells, cold and unyielding echoes of organic forms, hung suspended, bound by a network of chains. The title hints at the nature of our inner landscapes — a complex string of emotions, experiences, and the truths we cling to. Yet, the chains themselves represent an inescapable reality: the need for intimacy, however tenuous, within a vast and complex world.

In this Vogue Philippines exclusive, Coson delves into the inspiration driving her artistic process and the intentionality behind her latest exhibition. Inspired by connections with friends like Filipino designer Carl Jan Cruz and thinkers like Ursula K. Le Guin, she chases stories within the ordinary, revealing and illuminating the materials that (de)construct our lives.

Did your experiences growing up in the Philippines influence the way you perceive objects and their potential hidden stories? How does this translate into your choice of everyday objects like crates?

I have always been drawn to common and often overlooked objects that we might encounter every day, reflecting our lives back to us. For my most recent exhibition at Silverlens Gallery New York ‘In Passing,’ I took inspiration from fruit and vegetable crates which are a frequent sight in London’s East End. These produce crates are often stacked in different geometric arrangements on the street by market stalls or as temporary extensions to small business’ storefronts momentarily transforming and disrupting the architecture of the city and its flow. These ubiquitous crates became a fascination of mine as a mysterious object representing circulation, containment and openness. Once brought into my studio, they seemed to have come from long journeys arriving with different levels of wear, some banged up, bent, covered with export stickers, like stamps in a passport. I see these containers are conduits of stories and narratives from a life spent perpetually in transit, belonging and headed to everywhere and nowhere in particular, bearing witness to that which is transacted, exchanged and transported.

The use of handwoven linen seems to be significant. Is there a personal connection to this material, perhaps from your upbringing or cultural heritage as a Filipino?

Linen is a material far older than cotton (which is commonly used as artist canvas) yet it is something we still commonly see today. I wanted the works to have an almost artifactual quality to them like these could be plans of a city long gone whilst simultaneously depicting something we recognize as being made of a synthetic material (plastic) so attached to the present. I like that ambiguity, the flipping back and forth in time.

Whenever I come to the Philippines, I always make it a point to visit the studio of fashion designer Carl Jan Cruz who is a dear friend and another reason for my fondness for linen. We can sit there for hours exchanging ideas, laughs, and sometimes art. His studio is dotted with several of my works from twelve years ago to now and I have archival pieces from his graduate collection in my wardrobe as well as his latest garments. One of the oldest things I have of his is a black linen top he gifted me for one of my first shows which I have consistently worn at least once a week for over a decade. Needless to say we are both in awe of its survival and laugh about my enduring love for it. But most importantly I’ve been inspired by how well he can manipulate this stubborn fabric and masterfully deconstruct it to bend to his will the way only he can.

You combine traditional printmaking techniques with physical gestures. Why is this interplay between established methods and personal intervention important to your artistic voice?

I’ve long found printmaking or print-adjacent techniques to be an ideal way to approach themes that interest me as a way to capture the residue of something, whether physical or temporal. For ‘In Passing,’ I devised a unique way of mark making which I spent months practicing, tinkering, and perfecting as a means of imposing my own gesture upon the serial and modular systems of the mass-produced crates. I would describe the technique for the works in the show as a mash-up of frottage, relief printing, and calligraphy, something I would probably consider as just outside the realms of “proper” printmaking. I wanted to find a way to concentrate the industrialised logic of sameness of the crates, but also portray life and human gesture and intuition within the rigid structural formations.

While utilizing standardized objects like crates, you acknowledge the inherent individuality of each print. How does this embrace of the imperfect within a seemingly systematic process contribute to the overall meaning of your work?

For the large painting in the show, I stacked the modules to create a suggestion of a vast cityscape whose surface and volume appear and disappear between lashings of thick black ink representing what was once there, only briefly, yet left a mark permanently. Its potential contents are withheld from the viewer but their weight and materiality are felt through their towering presence in the gallery.

In Some place, within here (2024), why did you choose to use aluminum-cast oyster shells for this piece instead of real shells? Were there practical or symbolic reasons behind this decision?

The entire installation was made using five real Philippine-grown oyster shells that I had sourced with the help of Jordy and May Navarra from Toyo Eatery who are friends and frequent collaborators on a variety of projects. I sent molds from 5 original shells to the UK then had them cast in aluminum just outside London into an edition of 600 which I strung together with chains mimicking oyster farming techniques in the Philippines as well as echoing the working of one of my favorite artists, Felix Gonzales Torres. It is illegal to ship shells out of the Philippines, nor did I even consider it necessary to the work. I liked the challenge of creating an immersive space with a couple shells handed to me in a single envelope, inexpensive materials and hours of patience, blisters and bandaids.

Your use of the transport crate seems to suggest a vessel of both physical objects and memories. How does the act of transforming these utilitarian crates into art help you grapple with the passage of time and the complexities of memory, especially in the context of displacement?

I always return to Ursula K. Le Guin’s essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction as a conceptual tool to understand the significance of the crates. Briefly, it is retelling of the story of the human origin story replacing the spear, the dagger, the sword and individual heroism with the pouch, the receptacle or the container as humanity’s most significant and earliest inventions. According to most western tellings of human history, we transgressed the animal world once man started making tools for hunting and thus were able to dominate all other animals and beings, however, I am in agreement with Le Guin’s assessment, that the significance of the carrier bag (or container), is worthy of a revision. It is what holds and what carries that sustains us.

Your art explores themes of diaspora and the movement of people. How does your own experience of moving from the Philippines to the UK inform your work, both in subject matter and artistic process?

I’ve always been fascinated by how the world we exist in is formed by the cross-pollination of multiple and overlapping cultural exchanges as a result of the circulation of goods, capital and people. Living so far away from the Philippines, I naturally wonder how everything else arrived here and the journeys that they took and are still yet to take. The crates are essentially a medium of that movement and symbolize the porousness that I attempt to highlight in my practice.

- Raising Hope: How Ciara Marasigan Serumgard And Farrah Rodriguez Are Retelling The Story Of The Philippines’ First Peaceful Eco-Activist Movement

- Raising Hope: Dr. Celine Guillermo On Helping Children With Intellectual And Developmental Disabilities

- How Kat Alano Broke Free From Online Gender-Based Violence

- Raising Hope: Cultural Preservation and Community Empowerment for Indigenous People