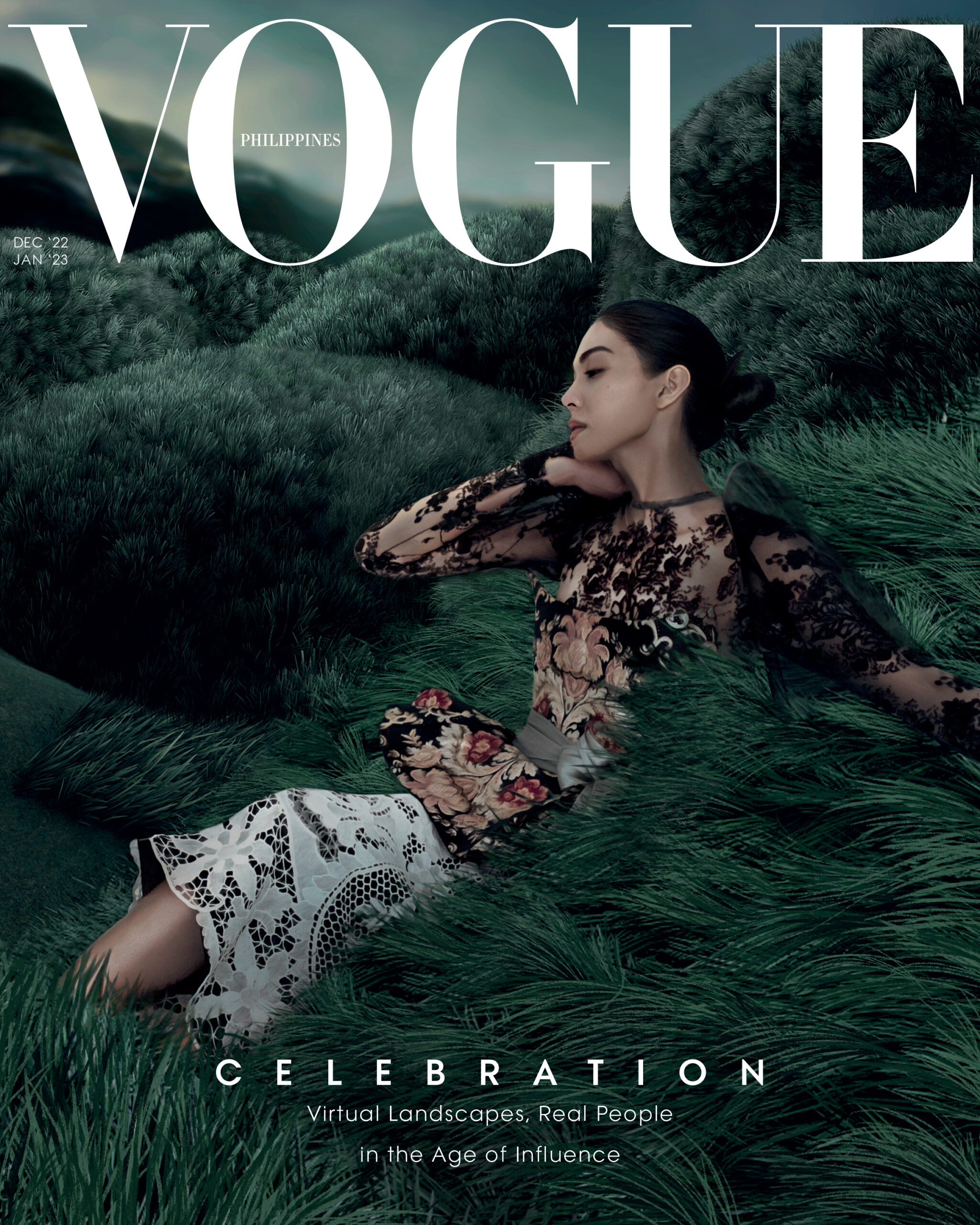

Bon Hansen Reyes balintawak. Avatar by Ivan Medrano, landscape by Bianca Carague, digital fashion by Tanya Pyanida of DressX

According to some tech execs, it doesn’t.

In a 2022 interview with The Verge, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg said he anticipated it would take at least five more years before “things would start to click and people would start to understand what we were putting together.”

Banking on becoming the center of “the Metaverse”—a term that originates from the 1992 science fiction novel Snow Crash and denotes an immersive alternate reality accessible via tech—the company is investing heavily in virtual reality hardware, such as the Oculus headsets, and VR software development, such as the social platform Horizon Worlds. In 2022, it announced partnerships with Adobe and Microsoft to integrate commercial tools (including the dreaded Teams) into virtual reality.

Meta’s overarching vision is to replace the bulk of “real life” with appealing virtual analogues: Why commute to work when you can collaborate in cyberspace? Why bother getting ready for a party when you can roll up to one from your Oculus headset? Still, it can be difficult to imagine having the desire to sit in a VR meeting, gazing for hours at your colleagues’ avatars without a complimentary croissant in sight, or hang out in a blocky VR living room when your friends are just down the road.

The implications for highly visual or technical fields are clear, and surgeons and architects may rejoice at the possibilities of training or designing in three living dimensions. But Meta’s complete vision excludes around 37 percent of the world’s population without internet access, let alone the significant processing power needed to access VR, and ignores the nature of work and play outside of white-collar enclaves.

Finally, it chafes against what so many have discovered after the world’s partial, post-lockdown reopening. The sparkle of a recently rained-on garden; the hush of an air-conditioned cinema seconds before the movie starts; the bliss of dancing together in a nightclub or the communion over a home-cooked meal: these are whole, sensory experiences that a virtual environment may never come close to replicating.

Millions of people already flock to online worlds for fun—and these, combined with social media, augmented reality experiences, and the aforementioned VR innovations, can be seen as a patchworked Metaverse stitching itself together in real-time, outside of Meta’s jurisdiction.

Massive multiplayer games like Roblox, Fortnite, and Minecraft contain myriad experiences for every kind of gamer, from blood-thirsty fighters to meditative builders or absolute beginners. There, digital socializing is a far cry from posting photos and exchanging messages. Users bond over melée battles or patiently recreating Disneyland block-by-block. In other words, virtual worlds are beloved precisely because they are unrealistic. The appeal lies not in replacing the world we live in, but in the avid and absorbing fantasies that expand our limited reality.

And the idea is hardly new: Second Life, a massive multiplayer game often cited as a precursor to the Metaverse, has been online for close to two decades. The platform is populated with the ethereal fairies, exaggerated pin-up models, and many-headed dragons that many people, it turns out, dream of becoming.

The idea of using virtual worlds to escape “real life” may seem toxic or frightening to the uninitiated. The mental image of a gamer hunched over their PC beside piles of empty ramen containers, friends, and family long forgotten, is hard to shake. Yet video games have been proven to improve reflexes and cognition, while studies have shown how some virtual experiences can increase empathy, soothe anxiety, or even reduce pain.

Bianca Carague hosts her therapeutic environment, Bump Galaxy, on a Minecraft server, using aesthetic elements such as shimmering seas, floating islands, and sublime temples to host creative therapy sessions or encourage mindful individual exploration. These settings offer a safe reprieve from the tension and bustle of real life, far away from the dizzying frenzy of many multiplayer games. They bring the serenity of an idealized natural environment to users who may well be hundreds of miles from unspoiled forest or shoreline, channeling the medium’s hyperreality to evoke feelings of wonder and joy.

“Instead of presenting a monolithic ideal of a ‘true’ Filipina, the avatar represents the multifaceted nature of living in an archipelago defined by extreme diversity.”

Unlike legacy social media, which depends on pruning the image of your life into an idealized “personal brand,” the Metaverse offers, in theory, nearly unlimited potential for creating your self-image. For some, this opens up the age-old question of who we are beneath our external representation, which parts of our personality will still shine through when our avatar is reduced to a glowing sphere or expanded into an angel with a thousand eyes. The next generation of “online selves,” with all their potential freedoms, encourage us to closely examine our own identities and the social or cultural contexts that compose them.

Using artificial intelligence, artist Ivan Medrano generates an avatar from over 1,000 likenesses of Filipina women that appears to be the “archetypal” Filipina at first glance. But her ghostliness—the uncanniness that resides in the blur between individual faces and an aggregated image—reveals how every archetype is unstable. Instead of presenting a monolithic ideal of a “true” Filipina, the avatar represents the multifaceted nature of living in an archipelago defined by extreme diversity.

Interspersed with the three archetypes are images of our model Taki set in Carague’s imagined landscape.

Digital fashion has been most successful when satiating our collective hunger for the unreal, giving people the ability to dress their game avatars—or even pre-taken photographs of their ‘real’ selves, in the case of services like DressX—in outlandish garments. From iridescent ballgowns to cyber-gothic exoskeletons, the impossible becomes accessible at a much lower price point than haute couture.

Meanwhile, the lucrative space of in-game purchasing has sparked collaborations between the likes of Fortnite and Balenciaga, or Louis Vuitton and League of Legends. Standalone digital fashion houses espouse the eco-friendliness of their offerings, enabling people to express their sartorial side without feeding into wasteful trend cycles. But more than merely reducing overconsumption, these projects captivate by pushing the boundaries of what is materially possible.

With the creation of digital terno, TernoCon enlivens traditional dressing with otherworldly forms rendered by DressX and Lablaco. Time-honored and ultra-modern, these garments express how our ancestry is inextricably entwined with our future and carve out a place for “craft” among the slick aesthetics that so often denote digital fashion.

Many proselytizers of virtual reality boast that these digital worlds will dissolve the differences that sort our world into harmful hierarchies. That idea is uselessly utopian; virtual worlds, like any other social platforms, still breed discrimination and harassment, and not everyone sees their real-life identity as a skin they’re dying to shed.

It may well be better to think about how the emerging Metaverse creates friction between the real and virtual, encouraging us to rethink much of what we take for granted about our world. As the story demonstrates here, the “non-place” of virtuality won’t do away with identity, culture or history. Rather, virtual reality presents a chance to strengthen these ties through expansive experimentation, recombining the foundations of Filipino identity inside intimately unreal realms.

This story originally appeared in Vogue Philippines’ December-January 2023 Issue. Subscribe here.

Photography: Shaira Luna, Fashion Director: Pam Quiñones, Sittings Editor: Ticia Almazan, Model: Taki Shimada, Avatar Designer: Ivan Medrano, Landscape Designer: Bianca Carague, Digital Fashion: DressX, Lablaco, Producer: Anz Hizon, Production Assistant: Adam Pereyra, Digital Fashion: Akanksha Srivastva of Lablaco and Tanya Pyanida of DressX. Special thanks to Gino Gonzales of TernoCon