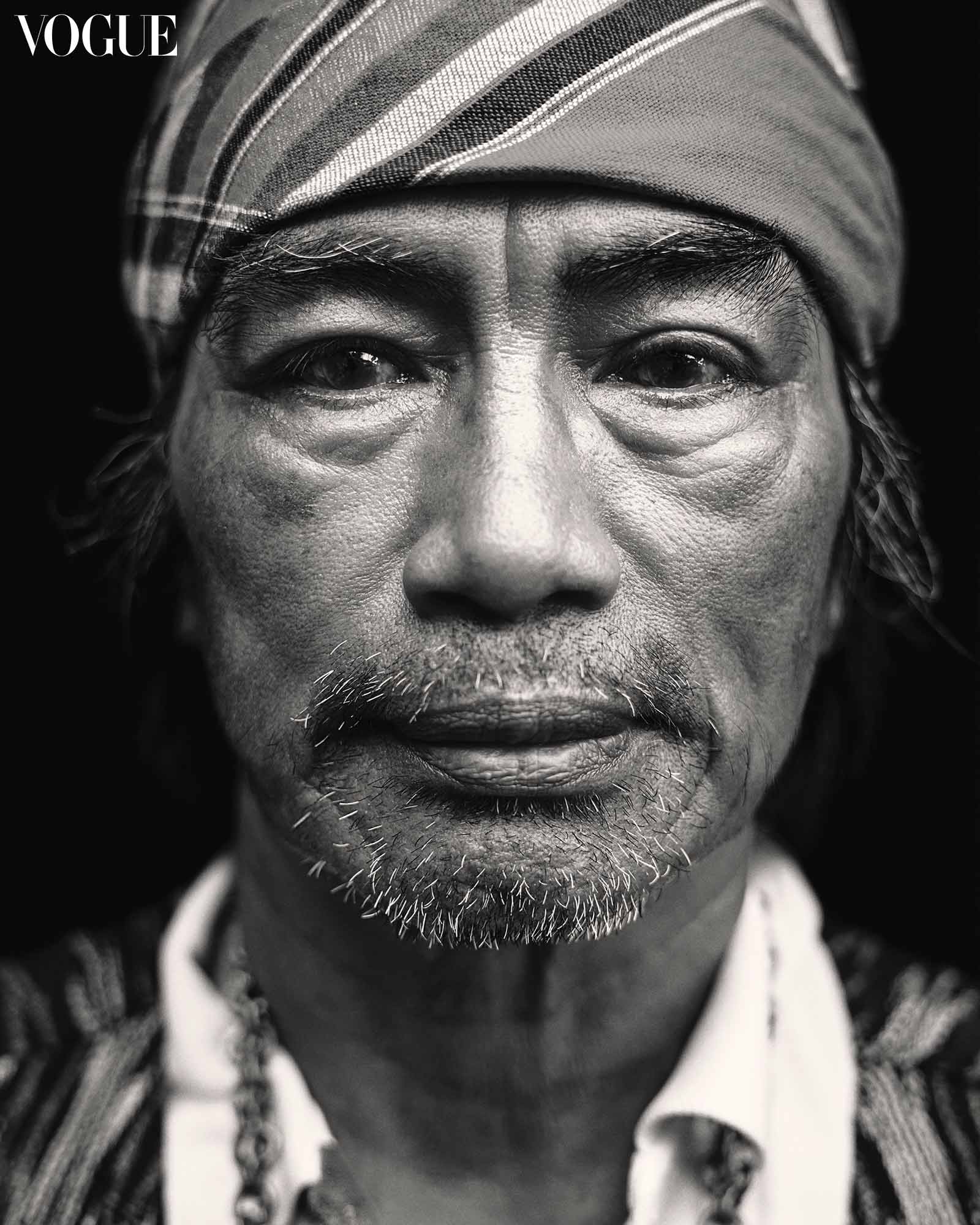

Photographed by Gabriel Nivera for the May 2024 Issue of Vogue Philippines.

Tboli artist Bundos Fara has grabbed the brass ring with a Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan.

Bundos Bansil Fara’s Workshop, found on one side of the main highway in Lake Sebu, has only a weathered tarp announcing “Brass Casting Center” to indicate his business, but you might spot Fara’s youngest son Jayson at the counter, carving up a wax mold of a mythological creature. Stacks of polished bangles and beaded gong necklaces are on display for souvenir hunters. You’ll find that they are, by any means, priced inexpensively, especially once you discover the laborious process involved in making one brass ring.

Fara is one of the three Tboli artists who were recognized as Manlilikha ng Bayan (GAMABA) or National Living Treasures in December 2023. The award is given to Filipinos whose “distinctive skills have reached such a high level of technical and artistic excellence and have been passed on to and widely practiced by the present generation,” according to the National Commission on Culture and the Arts (NCCA), the body that confers this award along with a PHP200,000 cash prize, a life- time monthly stipend of PHP50,000, and a state funeral. This is the first time a brass caster has been awarded since the GAMABA’s inception in 1992.

Brass casting is a skill learnt from one’s forebears, and Fara’s father and grandfather were all metalworkers. “I started in the process of brass casting when I was eight years old,” Fara says. Now 58, he has been working with molten materials for half a century. “My eyesight has gotten blurry.” Fortunately, he has a team of four sons working with him—one will be melting the wax, a mixture of beeswax, candle wax, and asphalt that forms a black putty; another will be tending to the blazing hot fires, fanning coals inside two holes in the ground, one for melting the metals, another for firing the clay molds.

Ginton is the Tboli god of metallurgy and the son of the supreme being Dwata. It is believed that he gifted the people with brass anklets, chain belts, rings, and swords—all of which still intricately adorn, protect, and tell the story of the Tboli today. As for the beginnings of brass, Fr. Gabriel Casal notes in his book T’Boli Art in its Socio-Cultural Context (1977), “The T’bolis give no indication of having ever possessed any knowledge of mining their own metals. These, they seem to have always obtained from old broken agong (gongs) or any of their other metal objects that break, and which they melt and re-employ for new substitutes.”

The recycling/upcycling of metals is still how Fara and other brass casters source their materials today. “We would melt down old gongs to create new items, but now there are many other things we can find at the junk shop, like padlocks, bullet shells, pipes.” The products they make are not strictly made of brass, but an alloy of brass, bronze, steel, and whatever else can be liquified in Fara’s smoldering hot pot.

The clay, meanwhile, is procured from a mountain in a neighboring region. It’s the same kind of clay used to make palayok, or earthen cooking pots. Earth, water and fire come together in the “lost wax” process of brass casting also known as cire perdue, one of the oldest types of casting. Fara demonstrates by making a single bangle: After etching a pattern on a tube of wax looped around an empty liquor bottle, Fara encases it with clay, with a nozzle extruding from one end.

The clay mold, once dried, is heated in one of the furnace holes until the wax inside drips out of the nozzle and disappears into ash. In the other hole, scrap metal is smelted down until it becomes viscous and lava-like. Fara lifts the clay mold with a long pair of tongs and places it on the ground. He then lifts the scorching red claypot full of liquid brass, pours its contents down the nozzle of the clay mold, and leaves it to set.

After it has cooled down, Fara breaks apart the clay mold, revealing the cast brass bangle inside. The unwanted bits will be broken off the bangle and melted again. Each wax mold is unique—even identical-looking tiny bells and are each forged individually. “I make all of this by hand, from the smallest to the largest,” Fara says. “Nothing is machine made.”

Though the wax is lost, it is replaced with some- thing more precious and more enduring. The art of brass casting in Lake Sebu may have become a commercial enterprise in the last few decades out of necessity and market demand. But the ancestral skills and techniques—and the spirit of Ginton—are still being passed down through generations, forged in fire.

By AUDREY CARPIO. Photographs by GABRIEL NIVERA. Producer: Patricia Co. Photographer’s Assistant: Adrian Dan. Special thanks to the Municipal IPS of Lake Sebu, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples, SOAS University of London, Comm. Reden Ulo of the NCCA, Marian Pastor Roces, Benjie Manuel, Hermelyn Jabagat, Cristina and Jovi Juan.