Gemma Cruz Araneta on her life in Mexico, her reluctant foray in modeling, becoming a public servant and cultural advocate, and when she’s writing her next great book.

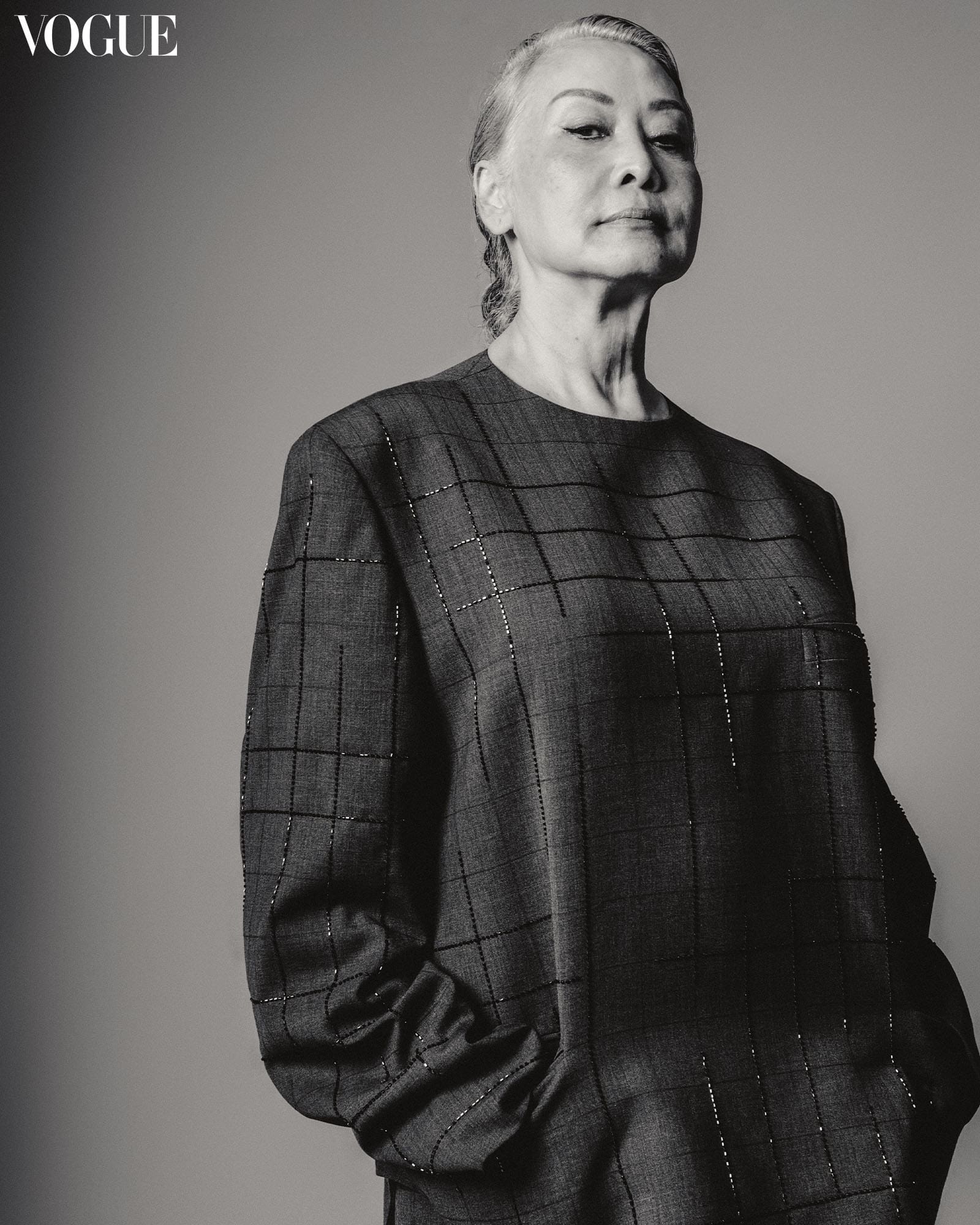

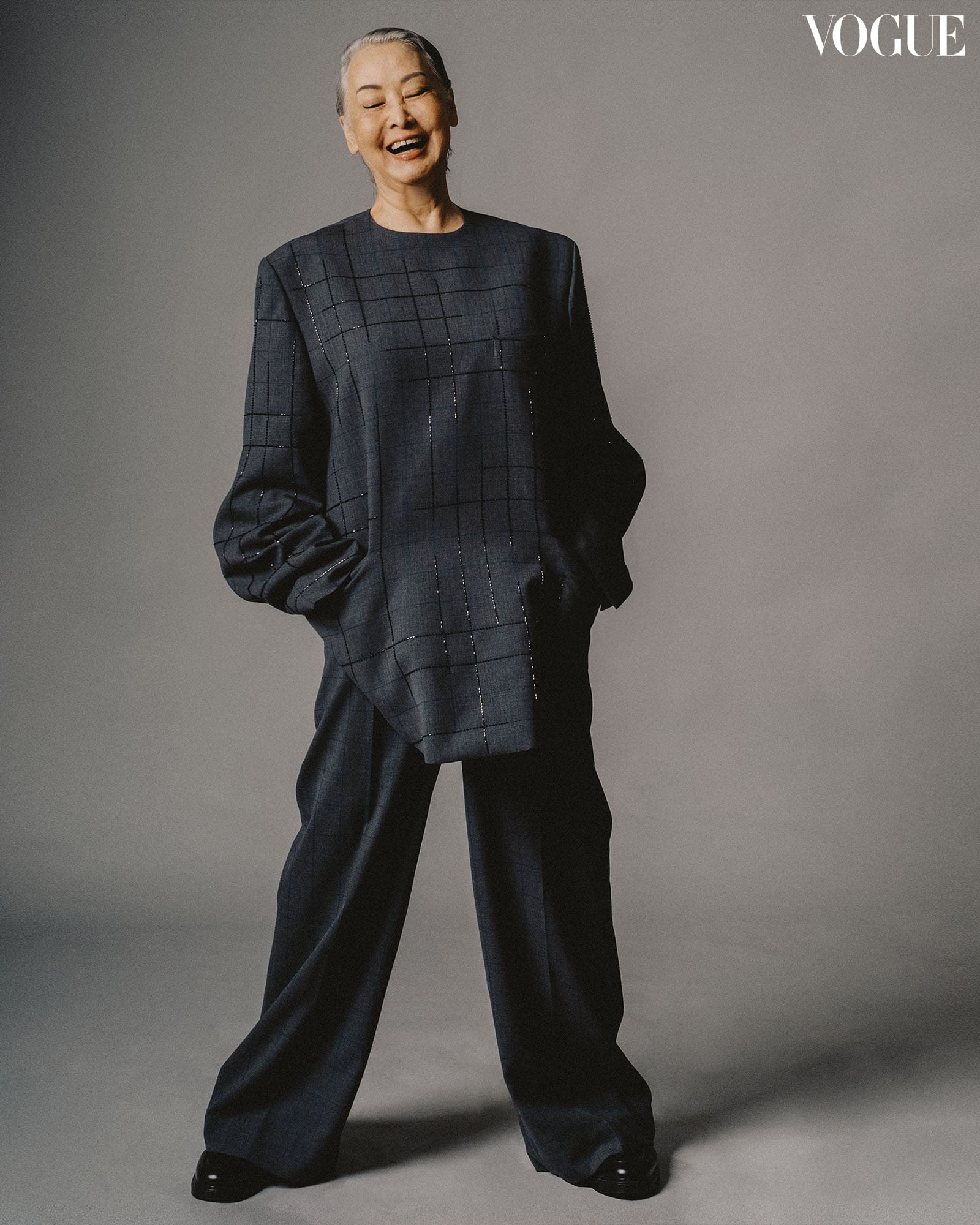

Gemma Cruz Araneta is still turning heads in her eighth decade. Standing 5’10” with a coiffed silver mane, she is easily the tallest, and most striking person in the room. Her very presence commands respect, emanating a knowing dignity distilled from years of living a life that can be described as wide-ranging and far-reaching, even colorful. She grew up with the greats looking over her shoulders: Filiomena Francisco, the first Filipina pharmacist, her mother the writer Carmen Guerrero Nakpil, and her uncle the diplomat-historian Leon Maria Guerrero. She calls Jose Rizal her great grand uncle.

Hailing from a distinguished family of letters, it must have come as a surprise that Gemma Guerrero Cruz would make a name for herself as a beauty queen—a move that behooved her uncle Leon to send a cable from Spain to his sister Carmen with the message, “Basta de barbaridades!” (enough of this nonsense!)

But she wasn’t just another pageant contestant, Cruz Araneta became the Philippines and Asia’s first international title holder when she was crowned Miss International in 1964, in Long Beach, California. Back then, she was aware of how pageants were being used as a geopolitical tool. Considering what was going on at the time—the United States of America was trying to shore up support for a war in Vietnam—it seemed that an Asian candidate would have a good chance of winning the title.

Four years later, in May 1968, Cruz Araneta would find herself in what was then North Vietnam with her husband Antonio “Tonypet” Araneta, whom she met and married shortly after winning the competition. They had both traveled as journalists seeking the other side of the story, the one that was not being reported in the media. Gemma wrote a book, Hanoi Diary, about that month she spent there, interviewing officials and female militia commanders like the young Nguyen Thi Hand, who singlehandedly shot down an American plane. She also toured heavily bombed areas and witnessed how the Vietnamese converted bomb craters into fish ponds and vegetable gardens. “I think that is my most important book,” she says when I pull out a signed copy of Hanoi Diary that I found in my parents’ library. The book was reprinted in 2012 after she was invited to return to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam to give a speech at the opening of a bomb shelter that was rediscovered underneath the Bamboo Bar of the Metropole Hotel in 2011. When Cruz Araneta stayed in the hotel in 1968, it was known as the Thong Nhat. She advised the current management to restore the hidden bunker and open it to the public. The advice was brilliant, because the bomb shelter is now a UNESCO heritage conservation site.

Having just read Hanoi Diary, I was amazed that Gemma, a 26 year-old young mother at the time, would embark on a mission that was full of risks; many parts of the city had been decimated by American bombs and every day there brought the possibility of being caught in an air raid. But the women she met in Hanoi had formed a movement called the “Three Responsibilities” that inspired her and taught her an important lesson about independence and freedom. “I saw how active the Vietnamese women were during the war. Once they mobilized themselves and took over the factories, medical centers, the farms, and took care of their families and children—when I saw how brave and determined the women and girls were, I felt the Americans were not going to win that war.”

Having lived in Mexico for so many years was a personal test, if not the supreme test

Perhaps the tenacity and determination of the Vietnamese women seeped into Gemma’s subconscious and galvanized her to take her own independent action later on. When Martial Law was declared, Tonypet and Gemma were red-tagged, so she decided to exit the Philippines with her two children, Fatimah aged nine and Leon aged four. She waited until Tonypet, then a political prisoner, was released from the Fort Bonifacio prison before leaving him behind for an undetermined future in Mexico. She wasn’t completely without connections—her uncle Leon was the ambassador to Mexico at the time—but for the most part she was an unknown, not a descendant of Rizal, and definitely not a Miss International.

Cruz Araneta recounts how she had to look for a job, and saw a posting for an English teacher in the classifieds. Over a telephone interview, she told them she had 30 years of experience. When the recruiter came to see her in person, he asked to see her mother. “I had to explain to him that I meant that I’ve been speaking English for 30 years,” she says, chuckling.

Luckily, she was hired on the spot to give English classes to Mexican executives of Johnson & Johnson.

Her teaching gigs had her commuting around the city from morning until evening, but she made it a point, upon her mom’s admonishment, to create a routine for her children by preparing three meals for them daily, even if she was working full time.

“One fine day,” Gemma continues, “a young Filipina lady named Anita appears at my door with her agent. She was looking for a modeling partner with similar features. I said, I don’t know how to model! Then the agent told me how much I would get paid, one fashion show was equivalent to one week of teaching. I said, Okay! I cut my teaching hours and had more time with Fatimah and Leon.”

After teaching English and modeling for three years, Cruz Araneta admitted that it was not what she really wanted to do. She yearned for something more scholarly so some friends suggested that she apply for a job as a researcher at the Centro de Estudios Económicos y Sociales del Tercer Mundo (Center for Third World Studies), a think tank established by a former Mexican president. She was hired and assigned to the Asian section. She remembers it as a very exciting and stimulating place to work, because she traveled to places like Nicaragua and Guatemala and had encounters with many Latin American intellectuals, writers, and political exiles whose books she was reading at the time.

When the center closed down after six years, she moved on to the United Nations Development Program where she “held the purse strings” of all the projects of the Mexican government. This time, her assignments took her to far flung rural places of Mexico, checking on irrigation projects and meeting with farmers. After three years of field work, Gemma was asked if she wanted to go to the UNDP in New York, “But, I felt that it was time for me to come back to the Philippines,” she says. It was 1990. Her kids were grown. The Philippines was changing.

Homecoming Queen

The return of the country’s first international beauty queen put Cruz Araneta back in the spotlight where she belonged. “The nation was calling her back,” says her son Leon Araneta. “Without a doubt, the nation is my mother’s true love.” In 1998 she was appointed Secretary of Tourism by President Joseph Ejercito Estrada. After Estrada’s short-lived term, Cruz Araneta was elected chairperson of the Heritage Conservation Society, which helped the Department of Education restore the Gabaldon School Houses, which were built during the American colonial period. The design of the schoolhouses are unique in that they married traditional Filipino architecture with modern American construction, resulting in airy, well-lit classrooms that were conducive to learning.

From 2007 to 2013, Gemma worked for Mayor Alfredo S. Lim of Manila as executive assistant and vice-chair of the city’s historical and cultural committee. “Things are very different at the local government level, “ she says, “you see the problems at close range and have to find instant solutions.” Although her main task was to organize all the commemorations of heroes and historical events, she also had to attend to indigent Manileños who needed food and medicine.

While working in the Manila City Hall, Gemma was able to save Botong Francisco’s most outstanding work, “Filipino Struggles Through History,” a massive mural commissioned by Mayor Antonio Villegas in 1963 that was hanging in the Bulwagan ng Katipunan of the Manila City Hall. It was declared a National Cultural Treasure but had fallen into disrepair, damaged by bugs, bad lighting, and water leaks. The National Museum came to the rescue when Gemma called Director-General Jeremy Barnes the morning after a stormy night during which part of the mural had peeled off. Considered one of Francisco’s greatest works, the restored mural is now permanently installed in the National Museum of Fine Arts for the public to view.

Cruz Araneta has been striving to put forward the next generation of heritage advocates; when she was chairperson, the Heritage Conservation Society recruited members in universities and colleges with faculties of architecture and engineering. “I’m doing the same thing with the Rizal family,” she says, “The torch has to be passed on; there has to be a changing of the guard. Whenever someone wants an interview about Rizal members of my generation answer the questions. We are in our late 70s and 80s—what if we die tomorrow?”

Lately, she’s been mulling over writing her memoirs. She remembers that her mother, Carmen Guerrero Nakpil, was also in her 80s when her daughters insisted that she write down her life story, lest Ermita before the Second World War be forgotten for good. “But whenever I say I’m going to write my memoirs, some of my gentleman friends pretend to be alarmed and ask , ‘am I going to be included?’ Well, there’s a price if you want to be included,” Gemma says, pausing. “There’s another price if you don’t want to be included!”

After writing, translating, and co-authoring a total of 10 books mostly about Philippine history, Cruz Araneta feels that it’s time to focus on her own personal narrative, particularly about her Mexico phase which set her on her career path as a public servant and cultural advocate. “I still think that my having lived in Mexico for so many years was a personal test, if not the supreme test…I told myself, it’s time to inject substance into the form.”

I ask her when she’s going to start writing her memoir, gentlemen friends be damned.

She laughs. “Tomorrow.”

By AUDREY CARPIO. Photographs by LLOYD RAMOS. Beauty Editor: JOYCE OREÑA. Styling by NEIL DE GUZMAN. Makeup: Angeline Dela Cruz. Hair: Nhot Bituin. Producer: Bianca Zaragoza. Nails: Extraordinail. Multimedia Artists: Gabbi Constantino, Tinkerbell Poblete. Production Assistant: Bianca Custodio. Photographer’s Assistants: Javier Lobregat, Ruel Constantino. Stylist’s Assistants: Jillianne Santos, Kyla Uy.