What would the stench of corruption actually smell like? Could you mass produce Proust’s encounter with the madeleine? Does nostalgia have a scent? Enter Toskovat, a perfume brand seeking to bottle memories as a scent.

The mysterious brand has built a cult following for its unique fragrances that are blended with bizarre notes and come with evocative, but opaque, descriptions. In the story for the popular “Age of Innocence” fragrance, which has an oud and vetiver base, sweet children on bicycles meet the sudden screech of tires. It begins with notes of bubblegum, cotton candy and strawberry, which is then contrasted with scents of gasoline, rubber and car seats.

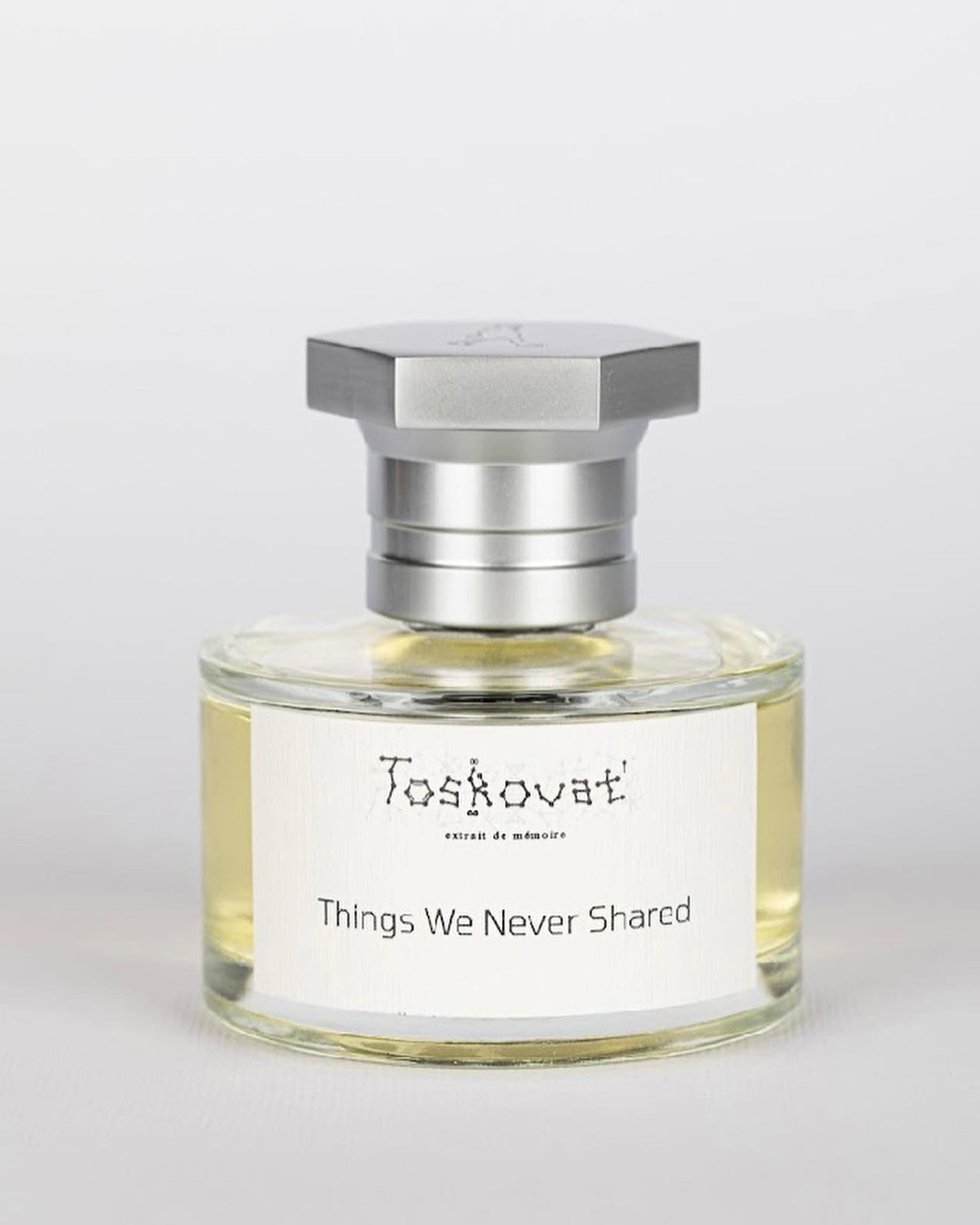

It gets more abstract, still. Notes in the divisive “Inexcusable Evil” include gunpowder, blood, iodine and rain, while “Anarchist-A” lists credit cards, plastic bags, priests’ robes and holy water as scents. Even in the middle of sweetness, there will be dark notes of poison, as seen in “Things We Never Shared,” which has a floral, oozy top and toffee and cacao base. Some scents are more sanguine: “Génération Godard” is a tribute to the cinema, with a blend of popcorn, cola, tobacco, and sweets. On the skin, each fragrance is incredibly pungent, with powerful staying power. And, whether placebo plays a role or not, when you take a whiff, you get the picture.

“The story side of perfume is what I thought was the most important,” says creator David-Lev Jipa-Slivinschi, over Zoom from his home in Romania. After studying to become a screenwriter, the 25-year-old graduated during the pandemic when the film industry was at a standstill. At a loss for what to do, he decided to try and continue to tell stories through a different medium. During a time when travel was impossible, he decided to create scents that would transport people places. “We are trying to capture these small fragments of a universal experience,” he explains. “They’re not my memories, they’re just human memories.”

In true Gen-Z fashion, he turned to the internet. “You can learn almost everything from your bedroom,” he grins. “Fifteen years ago, there were less perfumers available for work than astronauts, but now, it’s such a growing community, and everybody is so friendly.” Now he works with over 400 ingredients, but he started with 15 essential oils and fragrance starter kits.

When he meets trained perfumers from old French houses he observes that they are “really boxed into the classic way of building chemical formulas.” He thinks that his self-taught approach gives him an advantage – “I think that’s actually one of our strongest points in this industry – that we’re not afraid to break the rules.” That means that Jipa-Slivinschi remains unfazed about the marmite reactions to the brand, where opinions are split between people viewing Toskovat as an edgelord aiming for shock value, or as a godsend shaking up a tired industry. “We don’t specifically aim to make something controversial,” he says. “I think it’s an inherent result of staying true to ourselves.”

How can a new perfume smell like a memory?

It’s quite a philosophical endeavour. For example, I made a scent inspired by going to the cinema. It’s a special ritual to my heart, and I feel like it’s a dying event as people aren’t going as much anymore. I tried to capture a specific old cinema room that I used to go to, but at the same time, make it universally recognisable for everybody. That’s why I made popcorn and Coca-Cola accord. Behind the darkness and personal touches, you also get these fizzy and sweet smells that speak to everybody. It’s trying to bridge the gap between personal and universal.

How to you approach creating notes for a new scent?

Some perfumers make the chords in isolation, then try to integrate them in a finished perfume, but I don’t really like that way of working, because you’ve got so many variables that can affect the finished result. I think about the mood or the emotion that I’m trying to portray, then make this short sketch of what notes would be ideal to include and what are actually manageable from a chemical standpoint. You can make a dark, mouldy, woody perfume and a fizzy, champagne one, but it’s going to be very difficult to portray both at once. You have to decide what’s manageable from a chemical standpoint. When I tried to capture the smell of old, dirty bales of money, I started by looking at what’s inside it – what molecules evaporate when processing cotton, what’s inside plastic or ink – and then we try our best to mimic it. We’re more like caricature artists than painters.

When the notes are as abstract as car seats or holy water, how do you translate them into scents?

Sometimes one note will be the main character and act as the key memory that I’m trying to portray. In “Anarchist-A”, I knew I wanted it to smell like a wallet filled with money and credit cards. Sometimes it’s more vague. There are certain chemicals that you will find in a wide array of things – for example, linalool can give very different impressions, as it is found in over 200 plants, such as citrus fruits, berries, pineapples and rose. We noticed that people really gravitate to the wilder notes – I think they’re really tired of smelling the same things from the big brands, such as bergamot and jasmine. It’s up to us to give them a different story. At the end of the day, scent is really subjective. I can’t ever say I made a good scent, because somebody won’t like it or it won’t work on their skin, but I can say when I’ve made a good story.

Do you see some of your perfumes as more of a statement or would you wear all of them?

That’s a great question, and it’s one I think people don’t often ask themselves when they blind-buy our work. They think automatically if it’s in a perfume bottle, it’s supposed to go on skin, but it’s not always the case. Specifically “Inexcusable Evil”, one of our most-talked about creations. I never made it with the hopes of anybody ever wearing it. It was actually the other way around – I hoped it would be so brutal and jarring that people would hate having it on their skin, because the message and memory of it is wartime. But it seems I failed, because people wear it with ease. I can only control my art while I create it. Once I have released it to the public, there’s no point in me beating them over their heads with “you’re not supposed to wear it, this is art.” It’s up to them to decide. I personally find it weird that they want to smell like, you know, a soldier stuck in mud with concrete on them, but it’s up to them. I can only hope that the essence doesn’t get lost. I care less if they wear it or not; I care more about if they understand that the endeavour was to bring attention to something that’s miserable.

What is your own signature scent?

I don’t wear anything specific – I always wear what I’m working on so I can test it and see how it is going to perform. I rarely go two days in a row when I wear the same thing. The fragrance I wore the most from the first collection was “Age of Innocence”, as it was such a privilege to be able to work with an expensive material like natural oud. We source it from Thailand or Bangladesh and it is a special process, in which every tree needs to be bounded, numbered and harvested over a specific period of time. I wore it the most because it was a unique opportunity to wear something so special, not because it’s better or worse in any way than the other scents.

This article was originally published on British Vogue.