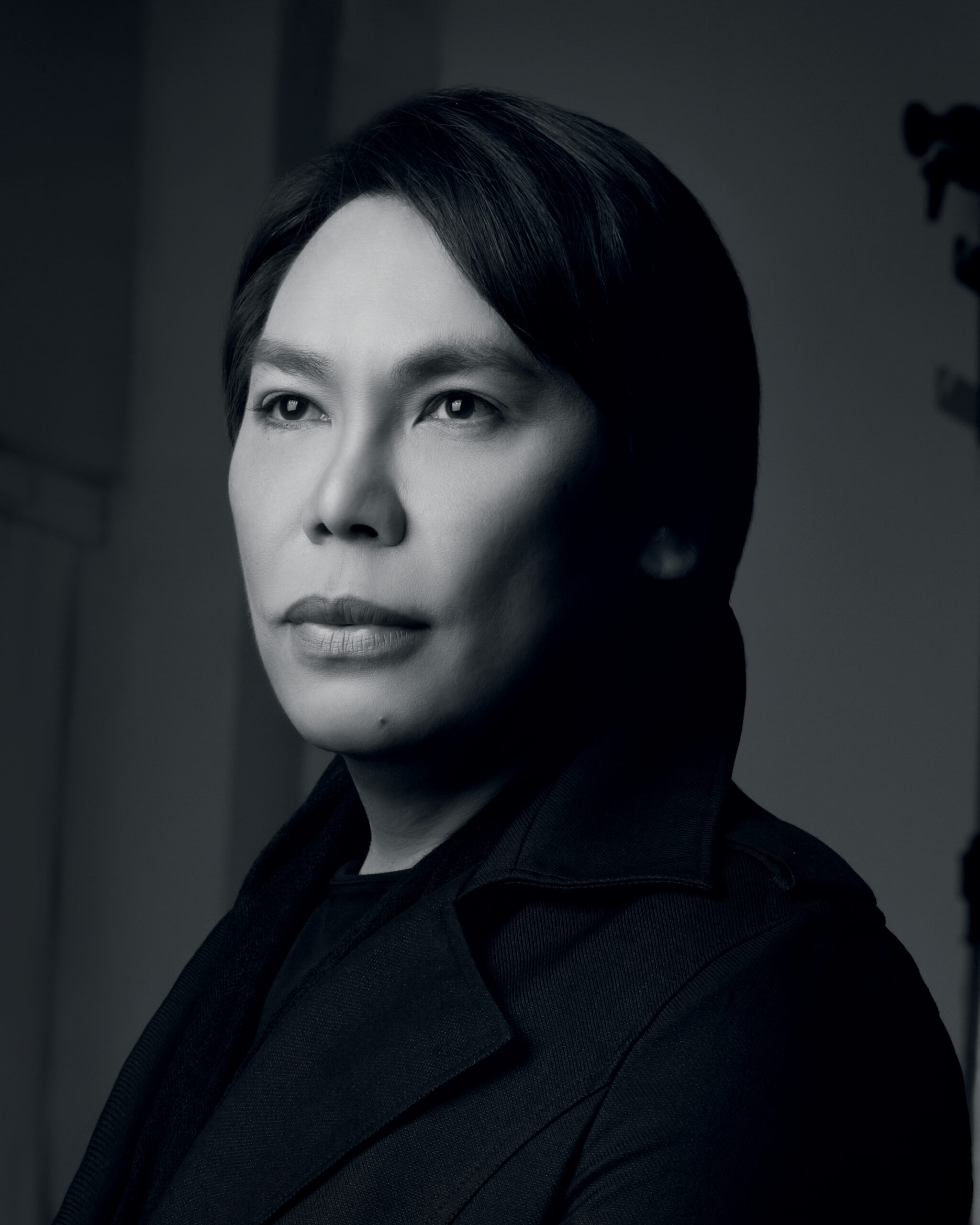

Photo by Aying Salupan

As a couturier, Cary Santiago has created shape-defying dresses with intention, emotion, and an imagination that’s unbound.

“Couture pieces are art pieces,” pronounces Cary Santiago. He is in his element—dressed in a loose, black top, black trousers, and an unfastened scarf—surveying the view from a high-rise apartment in Tsim Sha Tsui, overlooking the bustle of Victoria Harbor in Hong Kong.

“There is an intricacy involved, it should feel like a feast to the eyes, there should be an improbability there that is made probable through technique, and it should make people imagine and wonder,” he explains. “It should make people question the process but at the same time marvel at how it was created.”

Since 2006, after spending three years in Dubai and a year in Lebanon absorbing the techniques, skills, and the discipline of couture, Cary has been stirring up fashion discussion with his spectacular repertoire of specialization. He has subverted fabrics, morphing soft chiffon into rigid, sculptural shapes. Reconstructed contours into dramatic forms with precision pleating, and raising planes with embossing and fabric wrapping to create three-dimensional shapes of beautiful, painstakingly expert hand-crafted intricacy, his approach seems both scientific and architectural.

Unlike how couture may be associated with excess, his refined maximalism plays the reductionist card. “You can have an eye for beauty but editing is also very important,” Cary explains. “As a designer you will always have this urge to want to put everything in but there should also be a discipline of restraint. A check on weight, restrictions, and functionality. At the end of the day, I would want my pieces worn.”

Last March, Cary staged the Philippine Terno Gala featuring the Philippine’s national dress in his home base in Cebu. The show featured the arched sleeves in fantastical interpretations: laser-cut panels layered and contoured in an art deco column; winged, feathered and gilded on the other; and filigreed with scorpions and aviary mosaics in an away-from-the-body frock. “Post pandemic, I really felt the need for a meaningful gathering, for people to once again find joy in getting dressed and socializing,” Cary says. “The Terno has been a constant occasion-dressing request. And this normalization is good because I can see the pride in their bearing, the national dress is transformative. This is the purpose, to associate dignity and self-regard with every piece of Terno worn, and how important it is to be a staple in everyone’s wardrobes.”

It is the designer’s creative energy, his concise unwavering perspective, his singular point of view, and close relationship with clients who have a mutual discernment of his aesthetics that has made his brand so successful. He has had patrons with him as early as when he was 18 years old (when he first started), and those patrons have remained and expanded to include the sisters, daughters, and further extensions of the family. “For other people, they think that when you’re a designer, you just make clothes. No. There has to be connectivity,” he explains. “Designing is like psychology, you analyze what would look good with this person, what is her personality, what is her body shape, what will make her happy. It is never just my vision, the person wearing it is as important. When you create relationships with people and they love your work because you understand them, they will come back to you, time and time again.”

It is as if Cary looks to the future, but with a reverse funnel. He wants to do more ready-made off-the-rack offerings. He wants to reserve the big hours of time-consuming energy of couture for fewer clients. He also wants to see an institute created for young designers for them to get support in terms of fabrication, skills and business know-how. And, he would like to continue his newfound passion for painting. “Beauty transcends mediums, it can be in a detail of a dress, an unexpected sculptural creation, or colors mixed in startling ways when I paint,” Cary explains. “Beauty in its absolute form is when it evokes emotions, when it gives delight, and I am happy when I see other people happy looking at my work.”

“As a designer you will always have this urge to want to put everything in but there should also be a discipline of restraint.”

Cary started designing when he was 15 years old, helping out his mom who was a seamstress. With no formal fashion training, he was hired at 18 to be the assistant designer of Cebu-based fashion designer Nikki Crodua. After four years he opened up his own shop but had to leave it for an opportunity with a couture house in Dubai. Beirut was the second Middle East city he found himself in but again had to leave because of the 2006 Lebanon war. In the same year, he arrived back in Cebu and decided to stay for good. “In Lebanon, I created collections already but it wasn’t under my name. I have never really felt how it was being recognized as the creator of the pieces,” he says. “I didn’t realize that I wanted that.”

From the beginning, Cary sought to give significance to the extraordinary nature of couture. His winning piece in his first local show, the 2004 Philippine Fashion Design Competition hosted by the Fashion Design Council of the Philippines, was a Terno inspired by the Philippine eagle “Pag-Asa” with Jusi fabric dyed to look like feathers. He used about 5,000 varying sizes of real eagle quill which was then sewn on as a faux-and-real plumage on the dress. This piece gave him his first standing ovation.

For Cary, craftsmanship is as important as design. Working with a staff of 20, each dress takes about 100 hours to make. While he admittedly says he learned beadwork and moulage in the Middle East couture house. Details like pattern cut-outs, embossing, fabric wrapping, carvings, and precision pleating were all developed and honed in Cebu, without technical help of machines, or computers involved. “In between imagination and reality is work, the human element, and personal touch is at the center of everything. I cannot do what I’m doing without everyone who works with me,” Cary explains. “Execution connects imagination to reality. I sketch, shape, form, sample, decide on the techniques, and my team comes in and work their magic. I am not afraid to put in the work, I like the slow way of doing things, perfecting minute details and figuring out complexities because beautiful things take time to make”

A new chapter

“Mellow down,” Cary says of his current state of mind.

He shares that his best friend died during the pandemic and that changed him and his perspective. “I realized I don’t really need all of this when I die but I do need to take care of myself. I am grateful that I’ve come to a point where I’ve created a niche in the field of couture appreciation. I would like to think that I was able to inspire young designers. I just want to be remembered as a designer who was not as popular but contributed to the elevation of the craft in terms of technique, construction, and design.”

Granted the direction of his statement, it is not surprising that his production has scaled back to 50 percent its usual capacity. Changing the perspective of socially-conditioned conventions of event dressing is one of his legacies but creating couture is more for personal gratification.

“I am happy where I am right now, I feel fulfilled. I’m not dictated by the constant urge to compete with myself anymore,” he says. “I started at 15 and I’m now 51, that’s a good full circle when you think about it. Now when I receive a compliment, a thankful hug, a personal message, it’s winning really. I feel like I have gotten the respect of the design community, I’ve been accepted, and that’s enough for me.”