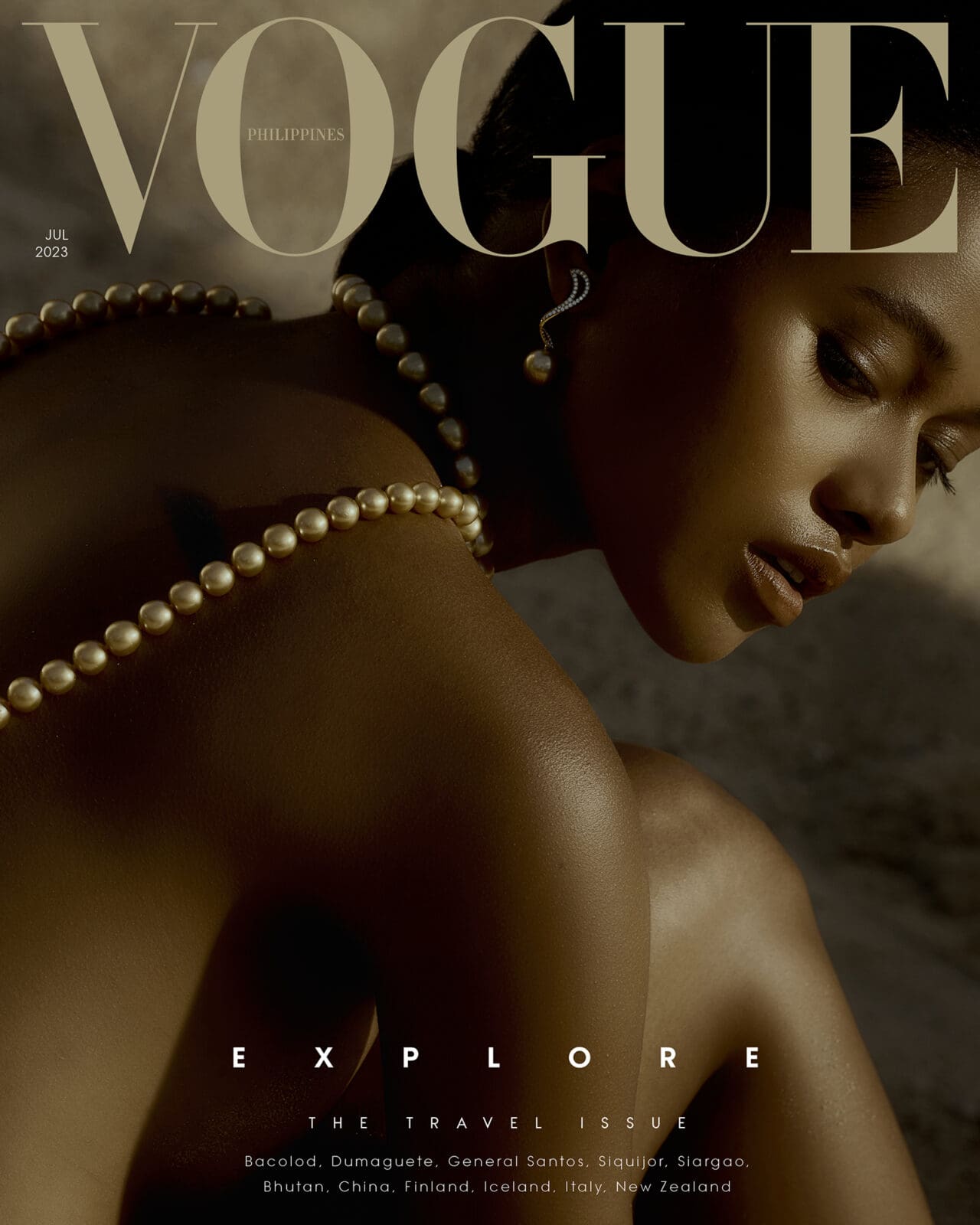

Bianca’s racesuit, DION LEE tank top, SWAROVSKI necklace, FENDI earrings. Photographed by Borgy Angeles.

Fueled by talent and tenacity, 18-year-old Bianca Bustamante is racing her way to the top of motorsport.

It’s never an easy road to the top. It’s even more challenging when that road is a racetrack. Racecar driver Bianca Bustamante knows this firsthand. As the only Filipina on the international racing circuit, she hasn’t just taken the road less traveled, she’s also blazing a trail for other female athletes.

Starting Grit

Bianca knew she wanted to be a racer ever since she first drove a go-kart at the age of three. The daughter of former go-kart driver Raymund Bustamante, Bia, as she’s also known, developed an interest in motorsport before she could even walk. “I had my very first racing suit and helmet at the age of one. The minute I could drive, it was all I could think of,” she says.

What is surprising was her early determination to pursue a career behind the wheel and her awareness of just how challenging that would be. “I think winning Macau when I was six was actually the pivot point in my career,” she says, then laughs at how crazy that sounds.

“I was in grade one and I told my dad, this is what we have to do for me to make it. I feel like I’ve got what it takes but it’s up to you to take that risk on me,” Bianca shares. “If you’re willing to, I’m going to give it my all.”

If there’s anyone who knows just how demanding racing is, it’s her dad, Raymund, who gave up his own racing career because of how expensive it was to compete. His decision to support Bianca, however, reignited the dream.

“Coming from a very middle-class family in the Philippines, we just couldn’t afford it. A single race abroad can cost around PHP150,000. My dad had to work three jobs and move away to be an OFW in America,” she says, adding that her dad would even sleep in a garage instead of renting an apartment so he could give her that money to race.

What made Raymund and wife Janice take a gamble on their daughter was her obvious talent and her tenacity. “It amazes me that my parents supported me even though it’s not a common sport in the Philippines, especially for women,” Bianca says. There was no clear path for her to succeed in motorsport; she would have to pave this way herself.

Instead of entering grade school, Bianca asked to be homeschooled so she could devote more hours to train, conscious of the fact that she also had to start going to the gym to be as physically fit as the boys she’d be competing against. While her dad worked abroad to fund her career, it was her mom who would drive her to and from races. By the age of eight, Bianca had won almost everything there was to win in karting in both the national level and the Asian region. With extremely limited opportunities for motorsport in the Philippines, the next step for her was to move to the United States to compete.

Bianca also had to learn how to speak to possible sponsors. What might have been considered a disadvantage was used to her benefit. “I would share my story and what I had won,” she says. “I’d tell them that I’m very hardworking and a fast learner and that if they put me in the team for a free drive, I promised I’ll perform.” And she delivered.

She also had a lot of experiences in racing where she was put down because of her gender. “Even though I was winning, there were some who would make me feel like I didn’t deserve it because it’s a man’s world and I was going into their territory,” Bianca says.

While she didn’t allow negative opinions to stop her, the pandemic gave her no choice but to hit the brakes at the peak of her karting career. After earning the Asian Karter of the Year title, Bianca suddenly found herself in lockdown. Even as racing restarted outside Asia, Bianca could do nothing but witness it from her home in Laguna. “I was watching them and I just kept thinking, ‘How come they get to race and I’m here when I’ve put in so much work’?” she says.

With her father also locked down in the Philippines, unable to work and with no extra funds, Bianca made the painful decision to hang up her racing suit and helmet. “I told myself, ‘We gave it our best shot. We fought hard but maybe some things just aren’t meant to be,” she says. Bianca decided to focus on her education with the hopes of becoming an engineer and maybe one day enter racing again as a female race engineer in Formula 1.

Just as she decided to step away from racing, fate it seems, had other plans.

Dark Horse

When Darryl O’Young, the professional racing driver, messaged Bianca a happy 16th birthday and asked how her racing was going, he didn’t expect to find out that she stopped competing. Darryl, who first met Bianca at a race in China, shares how impressed he was by her speed. “I didn’t talk to her for five years but I would follow her racing on social media. I always expected Bianca to do good things and race formula cars,” Darryl says.

The understanding of her situation dawned on Darryl. “I saw a lot of myself in her, a really hard worker who was ready to do anything to race.” While Darryl never intended to be a manager, he decided to speak with Bianca and her parents to see how he could help.

Darryl and Bianca both say it took a lot of convincing and begging, but he managed to get Bianca an opportunity to take part in a shootout for the W Series, a women’s racing series launched as recently as 2018. But she was emerging from a disadvantage: racing go-karts and nothing else, having never driven a single seater formula car before, and emerging from lockdown with no racing for almost two years; it’s understandable that no one expected her to perform well.

“But when Bianca has these critical moments, she always rises to the challenge and executes,” declares Darryl.

“I went there and drove my heart out,” Bianca says, her voice filled with emotion. “This was it. My whole life, what I’d been working for, my parents and all their hard work and sacrifices. The only opportunity for a free drive for a whole season and you’re in support races for F1? I couldn’t miss it. I couldn’t let it go.” She ended up being the fastest driver from that shootout and was given a seat in the W Series right then and there. Dark Horse, the name of Bianca’s community of supporters, is certainly a fitting moniker.

Having secured one of only 18 seats in the W Series, Bianca earned the biggest opportunity of her career and a colossal challenge. “I went from no racing to Formula 3 cars. It was the biggest job of my life,” she says. Bianca would be racing alongside women who had years of experience driving formula cars and were competing during the pandemic. Many thought she just wasn’t ready or experienced enough, but Darryl believed in her. “The moment that I decided that I wanted it, that’s all it took, you know?”

Bianca rapidly grew into the role, learning how to drive a Formula 3 car in two weeks and joining a training camp at the Olympic Training Center in California. The intense workouts saw Bianca push herself to the limit, gaining 12 kilograms of muscle in 10 days. “For two years I wasn’t allowed to go to the gym. My whole body was no longer used to the training. It was so painful,” she recounts.

“As a Filipina, I stood there with a hundred and thirteen million Filipinos alongside me”

Driving a race car is so much more than sitting and turning a steering wheel. Racers are some of the strongest athletes, physically and mentally. As Bianca notes, “We accelerate and decelerate in 0.01 second and can go from zero to a hundred in two seconds. We train to be fit enough to withstand G-forces and things that are beyond the body’s capacity.”

Despite the physicality of it, strengthening everything from her neck to the grip of her fingers, Bianca emphasizes how vital mental strength is. “I do a lot of neurocognitive training because you need very, very fast reactions. When you’re going 280 km an hour and turning 180 degrees, you need to think fast. Not only can it make you win but it can also save your life,” she says. As she drove a formula car for the first time, raced through circuits she’d never been to, and stood in the public eye, Bianca’s mental strength also helped her quiet the critics and tune out any negativity.

Right Track

She has brought the Philippine flag to some of the most legendary circuits and improved her race craft. But scoring points were not the only highlights of Bianca’s W Series season.

Bianca also met one of her heroes: seven-time Formula 1 World Champion Lewis Hamilton. “He knew my name and that I’m from the Philippines,” she shares in disbelief. Bianca’s deep admiration for him isn’t based solely on his on-track achievements but also because of what he does off-track, still touched by the fact that he took the time to surprise and meet the W Series drivers during his own race weekend. “He’s been fighting for diversity. It’s one thing to be a driver but it’s another to have a voice and to actually use it,” Bianca says, and it’s evident that it’s something she’s determined to do as well.

The unexpected parallelisms between their histories are notable. Both are athletes of color from middle-class backgrounds. Both have fathers who worked multiple jobs while also occasionally fulfilling the role of karting mechanic to help their kids achieve their ambitions. Both, also, have brothers with disabilities. Bianca shares, as her eyes start to glisten, how part of her dream is to be successful enough to afford to bring her brother, who has autism and Down Syndrome, to watch her race for the first time.

For Bianca, receiving advice from Lewis himself was further proof that when you put in the work, the wildest of dreams can come true. “He told me, ‘I know it’s tough. I’ve been there. The journey is very long and you’re only at the very beginning. I’m not going to say it’s going to get easier, but you’ll get stronger and you’ll get used to it.’”

Making History

Early in January, Bianca signed with PREMA Racing, the Italian motorsport team known for successfully developing young talent. Bianca is one of only 15 drivers competing in the inaugural season of the F1 Academy, an all-women’s series owned by Formula 1 and designed to help female drivers join the Formula 1 grid. As a PREMA Racing driver, Bianca is now on the same path to Formula 1 that current drivers Charles Leclerc, Oscar Piastri, and Mick Schumacher successfully took.

In the first round, which comprises three races, Bianca qualified an impressive second during both qualifying sessions and left the Red Bull Ring in Austria with points in the bag. She explains how as it was the first race of the season, she took it as an opportunity to pinpoint her raw pace compared to everyone else’s. That pace quickly accelerated.

With anticipation for the all-women’s series building, the second round of races in Spain saw the 18-year-old cross the finish line first, achieving her maiden win racing a formula car. Shortly after the race, I check in Bia. “I was not expecting a win so early in the season but because of all the training and preparation, we were able to take it home,” she says. “I honestly still haven’t digested it properly! It hasn’t sunk in yet that we actually won a race, especially against such competitive and experienced drivers who are very quick.”

For the first time in history, as Bianca stood on the top step of the podium, wiping tears from her eyes, the Philippine flag was raised and the notes of our national anthem resounded to celebrate a race win sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile, the governing body for world motorsport.

As F1 Academy managing director Susie Wolff awarded her the winning trophy, Bianca recognized that her win represented the hard work of her entire team and that she is representing an entire nation. “Maybe to a lot of drivers it may not mean a lot, but to me it meant the whole world. My dream, my goal is to hear our national anthem in the motorsport world,” she says.

“As a Filipina, I stood there with a hundred and thirteen million Filipinos alongside me.”

By Raia Gomez. Photographs by Borgy Angeles. Features Editor: Audrey Carpio. Sittings Editor: Marga Magalong. Stylist: Steven Coralde. Makeup: Patricia Acejo of M.A.C Cosmetics. Hair: JA Feliciano. Producer: Bianca Zaragoza. Multimedia Artist: Gabbi Constantino. Production Assistant: Marga Magalong. Photographer’s Assistant: Pao Mendoza. Stylist’s Assistant: J.RO Alarcio. Shot on location at Tarlac Circuit Hill. Special thanks to the Governor of Tarlac, Susan Yap.