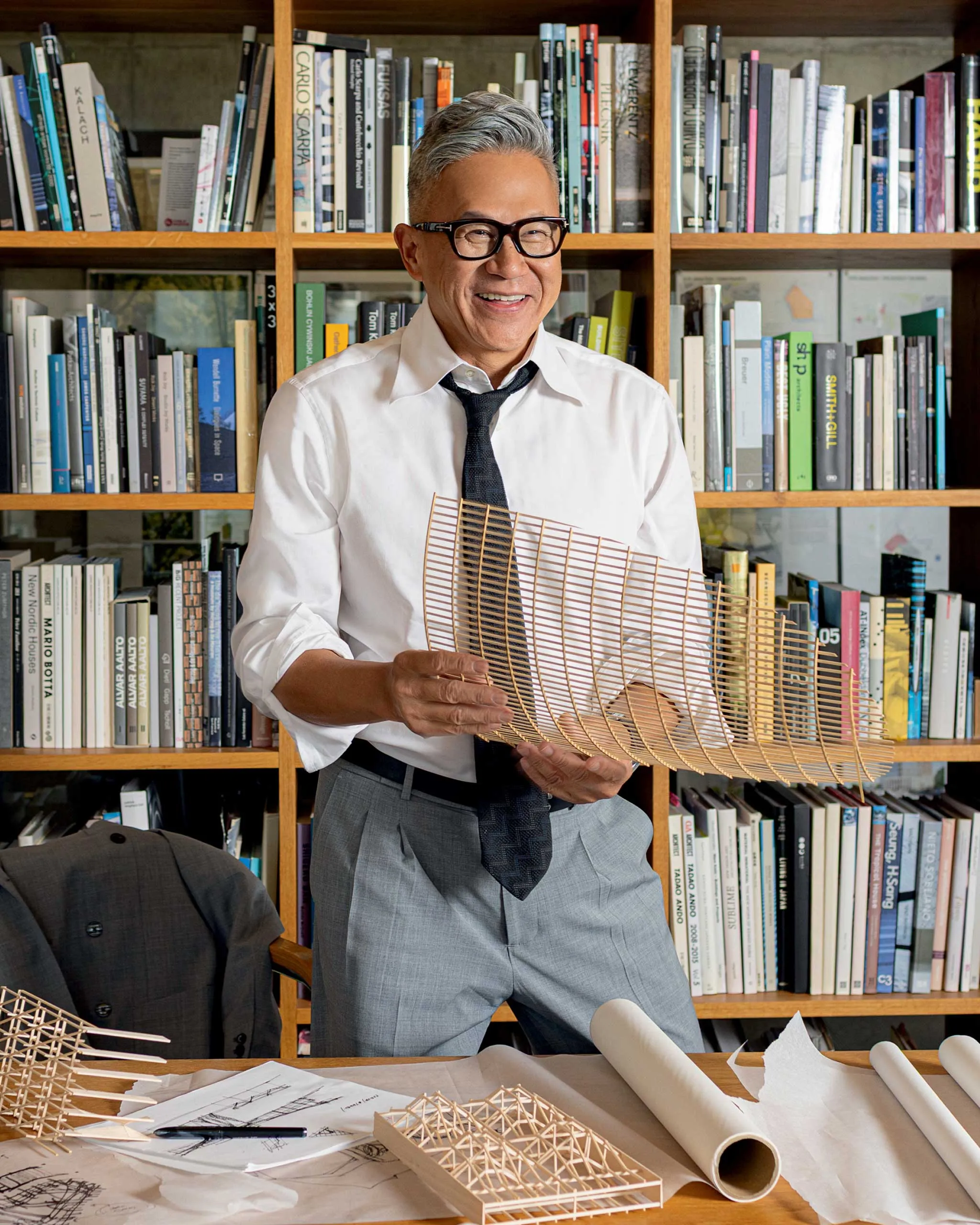

Sandoval has also led major projects for global clients such as Nike and Microsoft, bringing a systems-driven, sustainability-focused approach to large-scale architecture. Photographed by Celeste Noche

Oregon-based architect Gene Sandoval, who led the award-winning rebuild of Portland International Airport, has not forgotten his roots.

For many immigrants and international students, the airport that greets you upon arrival holds the promise of new life: a chance to define your future and build a home of your own. For Gene Sandoval, that gateway was the Portland International Airport, which welcomed him at 18 as he left Manila to study architecture at the University of Oregon, unaware of where the journey would take him.

After graduation, Sandoval settled in Portland and began his career at ZGF, then known as Zimmer Gunsul Frasca, working long hours as a junior architect. It would take eight years before he became an associate, but once he did, he quickly climbed the ladder. Several years later, at just 37, he joined the partnership, the sole brown face among 13 middle-aged white partners. Since taking on the role of design partner in 2005, the firm has expanded its reach and evolved in both composition and perspective, reflecting a more diverse, global outlook.

It is thanks in no small part to Sandoval that the highly acclaimed, newly redesigned Portland International Airport, the same one he first arrived in as a hopeful young Filipino, has a roof that is reminiscent of a bangka. “The opportunity to recreate the airport, which was my gateway to a new world, is such an honor,” Sandoval says. “It’s the American dream, but it’s also the immigrant story.”

The new terminal of PDX looks like a marvel of high-tech engineering, its soaring mass timber ceiling formed by a latticework of wooden slats. When the first phase of the expansion opened to the public earlier this year, the people of Portland were said to have teared up at the sight. It was beautiful, it was emotional, and it was proudly theirs. Sandoval had taken the idea of bayanihan and translated it for the Pacific Northwest, where the language is strongly grounded in the local.

The system he devised for the roof was inspired by his knowledge of boat building, having grown up in Coron, Palawan, where his family owned a shipyard and he would spend summers closely observing how the builders would resourcefully put things together out of simple materials. It was his first exposure to craft that was passed down from generation to generation. So when it came to the problem of constructing and assembling the roof of the airport, Sandoval suggested that they build with local materials and design it in a way that could make use of local skilled labor.

The roof, which spans six hectares, is made of Douglas fir harvested from sustainable forests within 300 miles, many of them managed by Native Americans. Throughout the terminal, placards tell you the provenance of the wood (which is a very Portland thing to do), acknowledging small mills, family-run forests, and other timber producers for their contribution to the airport. The hull-like structure was assembled by regional builders using familiar tools. No special fasteners or highly specialized techniques. “Any regular carpenter would be able to screw the rafters together,” Sandoval explains. “That’s the notion of bayanihan, right? When people help each other.”

“That Filipino notion became a vital part of the way I help my company design high-performing buildings.”

PDX has already won accolades, namely UNESCO’s Prix Versailles, which recognizes the most beautiful airports in the world, and a sustainability award from the Holcim Foundation. Its beauty is inseparable from its sustainability. The interior mimics a forest, with over 5,000 live plants and 72 trees bathed under natural light streaming from 49 skylights. These biophilic approaches not only help sequester carbon emissions but bring a sense of calm and peace to the usually stress-filled process of traveling. Again, Sandoval relates it to his upbringing. “For us, sustainability is survival. We recycled everything, used hand-me-downs, composted our food. That Filipino notion became a vital part of the way I help my company design high-performing buildings.”

This connection to his roots informs the way he solves design problems. The prismatic metal screen over the windows at the John E. Jaqua Center provides shade from the sun echo the bamboo reeds of a traditional bahay kubo. Meanwhile, the angular massing of the Sebastian Coe building of the Nike headquarters, rising above a pool of water, is another nod to his formative years in Palawan. “That could be Coron,” Sandoval points out, “with the black limestone cliffs and the lagoon.”

The work he’s done on healthcare complexes and corporate campuses have a deeper design ethos that is especially embodied in the sports facilities ZGF has become known for. The San Antonio Spurs Performance Center in Texas, built in 2023, is one of the most advanced basketball training facilities in the world, leveraging their background in healing and high-performance environments. “We developed a new way for athletes to train, recover, and also how to make them culturally stronger and resilient,” he says.

This holistic approach to athletics stems from his own past as a competitive swimmer with a varsity scholarship at UST, before he left for the United States. At ZGF, it expanded through an ongoing relationship with Nike founder Phil Knight and the University of Oregon since 2005 that has taken them on research trips around the world. “The whole practice is focused on this holistic approach to humanity. Our buildings are made to be comfortable, very humanistic. And we approach sustainability, not just in terms of saving electricity or water, but for people who use it to feel good, and perform better.

While the architecture of it all is highly technical, its essence comes down to the simple fact that people feel refreshed after a walk in a forest. ZGF’s buildings, impressively modern in their integration of wood, stone, glass, and light, are conceived as an interaction, bringing the outdoors inside, and creating spaces that feel warm, rooted, and human. “We don’t have a style, but we have this attitude of building really innovative buildings for the place, the region, but also for the human beings in it.”

At 57, Sandoval is entering what he calls his prime. “I finally felt that I was an architect three or four years ago, after all these years,” he shares. “It took a long, long time to master my craft, so to speak.” Even as a child, he always knew he wanted to be an architect, though he was not a very good student. But, he had this ability to “illustrate, to explain, to think about how things come together, to visualize experiences and create experiences.” He tells his two sons that what he’s learned is that success is not just about following your passion, but investing in what you are naturally good at. “That is your path to success, because that’s the way your brain is wired.”

ZGF’s most recent commissions are keeping him busy; they’re working on NFL facilities and a new airport in Aspen. While he can’t divulge much yet, he says the goal for Aspen is to be the most sustainable airport in the world, surpassing even Portland. I’m already wondering how he’s going to infuse Filipino elements into this snowy environment. “I can’t share!” He laughs, but insists that it’s going to be fantastic. “They have a strong history of environmentalism. Amazing views, snowmelt. How do you harvest water and wood? Because there’s all those traditional homes and wood cabins.” What Sandoval has proven over his career is that sustainability is understanding how humans have always lived in balance with their environment.

Beneath the monumental scale of his work, Sandoval’s purpose has always been human-sized: to help people become their best selves. He recalls the day he was invited to join the partnership. His immediate response was disbelief. “Have you seen this face?” he asked the partners. Unsure if he was ready, he took two weeks to think the offer over, seeking advice from his friends and colleagues, wondering if he should wait until they could all rise together. “They said, you gotta do it, man, because you are the symbol of change, and you can help propel this office faster.” Two decades later, that change is visible. Among ZGF’s 14 partners of ZGF are six women, five immigrants, and three LGBTQ members. “I believe that diversity is good for bringing up the very best talent and the very best ideas,” Sandoval says. “I’m really proud about the evolution of the firm, and I think our work is as good as it’s ever been.”

By AUDREY CARPIO. Photographs by CELESTE NOCHE.

Shot on location at the Portland International Airport.

- Brooklyn-Based Architect Carlos Arnaiz Has A Guiding Vision For His Brand—And The Country

- Architect Aya Maceda Centers Her Brooklyn Practice Around The Concept “Maaliwalas”

- A Glimpse Into What A Day Looks Like For Architect Arts Serrano

- Maria Grazia Chiuri’s First Project Post-Dior? The Restoration and Revival of a Roman Theater