Lake Tabeo, one of the four Mystical Lakes of Kabayan, Benguet, and one of the highest in elevation in

the Philippines.

Lake Tabeo, one of the four Mystical Lakes of Kabayan, Benguet, and one of the highest in elevation in

the Philippines.

Photographer Raena Abella embarks on a solo land journey around the Philippines, capturing images with a bit of luck, alchemy, and magic.

The temperature in Benguet had dropped to four degrees. Raena Abella is covered in layers of clothing as she manually grinds coffee beans and recharges solar panels for her customized rig. She has set up camp for the day after driving for hours along arduous stretches of winding, isolated roads, volatile photography chemicals at the back of her vehicle. It is only the 14th day of her solitary expedition.

Parked at the campsite of Lake Tabeo, the first of the four mountain lakes of Kabayan, Abella noticed an unusual tree growing horizontally over the serene and chilly waters. But because it was bitterly cold and there was no signal in the area, she decided to simply spend the night, hot water bottles tucked around her, not taking any photographs. The next day, she drove down to Vigan and then on to Currimao, all the while the impression of the tree persistently haunting her. Overwhelmed with regret, from Ilocos she ended up driving back to Benguet, returning just to shoot that tree in ambrotype. This time, Abella was prepared for the cold and for the absence of Wi-Fi. “I enjoyed being disconnected so much that I stayed for three nights,” she says of the experience. And this was how one of her most mystical ambrotypes was made.

Lifetime of Preparation

Abella spent nearly a year converting a borrowed company pick-up truck into a camper and mobile darkroom. Her plan was to travel around the Philippines documenting people and places using different types of photographic techniques. “I just want to travel alone and see if I can survive. Along the way, I want to take as many photos as I can, testing myself and discovering more about my country,” she explains. She took three months off from work, setting off on March 2 of this year.

As the trip is centered around the road network, the truck needed an all-terrain set of tires. For camping onboard, Abella added a roof tent for sleeping, a portable refrigerator and freezer, an additional air conditioner, an outdoor shower, an 84-liter water tank with faucet, kitchen equipment including a stove, pots and pans, camping chairs and table, a fire pit, an awning for extended shade, two 160-watt solar panels, and a small generator that can power appliances while charging her devices. The preparation alone would have been daunting for most women, but Abella is a trained diesel engine mechanic. She oversees civil works projects for her family business in construction and land development.

Alongside her day job, Abella pursues art photography, specializing in ambrotypes: images made on glass plates using wet plate collodion, an extremely difficult process. Developed by an Englishman, Frederick Scott Archer in 1851 (before film was invented in 1889), wet plate collodion requires the use of a large format camera and emulsion mixed by hand. Once mixed, the chemicals have a life of only a few minutes before they dry and become useless. The image must be taken and developed immediately. Many variables complicate the process, and shooting on location makes it even more challenging. Outdoors, there are the erratic factors like having the right amount of sunlight, extreme heat levels, and the possibility of sudden rains. In a previous attempt, “A plate was almost finished when a random fallen leaf dropped on top and damaged the image,” she recalls in exasperation. “Successful ambrotypes result from a mastery of the craft, but also a bit of luck, alchemy and magic,” she says.

Despite these rigors, ambrotypes are a rewarding art form. The monochromatic images produced through wet plate collodion have superior resolution and a tonal range that exceeds that of film. The image is a negative that becomes a positive when light shines through it from the front, against a black background. It cannot be optically printed like a film negative, is not mechanically reproducible, and is therefore a unique piece.

Aside from the ambrotype equipment, Abella brought along all her other cameras: two film cameras, two digital cameras, a GoPro, and a drone. “So far I’ve been using all of it,” she says. Earlier in her career, Abella worked as a commercial photographer, apprenticing with longtime mentor Steve Tirona. The lensman encouraged her to study the work of Sally.

Mann, whose eloquent images enchanted her and led her to take further courses: black and white photography and darkroom printing at the International Center of Photography in New York, platinum printing at the Penumbra Foundation in New York, and wet plate collodion at Gallery 44 in Toronto.

Prior to maneuvering the twisted roads of Mountain Province, Abella had some warmer moments in Baguio. She spent several nights at the de Guias compound Kitma, with Kawayan de Guia, Nona Garcia, Kabunyan de Guia, Kidlat Tahimik, and Mannix Tolentino. The compound is a gathering place for artists. That evening, they built a bonfire and visitors would intermittently come to sit around with them. She joined the family for rituals performed in honor of Kidlat de Guia’s death anniversary. “I watched Kabunyan get a tattoo while Mannix sang,” she recounts.

Abella then drove further to Sagada, where she experienced the Begnas, a sacred indigenous ritual performed as thanksgiving for the rice harvest. Tourists or outsiders are normally not allowed to watch the festival, which involves animal sacrifice, gong playing, and dancing, but Raena was endorsed by Cordillera-based photographer Tommy Haffala. “I waited for two days because there is no fixed date for the Begnas. It’s scheduled when the grains are ready for harvest, so the date is dictated by nature and by approval of the elders,” she says. “I’m amazed at how the people of Sagada still try to preserve their rituals. Even the younger generations actively participate.”

In the coastal town of Currimao, Abella found a place to stay at Sitio Remedios Heritage Village, which is owned by Pinto Art Museum’s Dr. Joven Cuanang, thanks to curator Carlomar Arcangel Daoana, who was working onsite. The artists Agnes Arellano and Billy Bonnevie were there preparing a piece for the Pinto Underwater Sculpture Museum. She went stargazing with them, while Agnes played her ukulele.

Some of Abella’s most memorable encounters during the expedition were these informal moments with artists. “Many of them are legendary. It was nice to have a peek at their everyday trivialities,” she shares. “Agnes and Billy brought along small musical instruments—bells, shakers and a large shell that could be blown like a horn. I had a glimpse of their travel habits, what they pack and how they work.” Agnes and Billy were overseeing the welding of the Inana sculpture onto its pedestal, and Raena notes how they were very meticulous with the delivery and assembly of the work, taking care down to the very last detail of its presentation.

Road to Faith

Many viewers following Abella’s Instagram stories observed dozens of images shot inside churches. “During this journey, I discovered my faith. I visited so many churches and prayed a lot,” she says. Each time she would see a church along her route, she would enter it and pray, initially in thanksgiving for the opportunity to embark on such a journey. Later her prayers transitioned to deeper intentions: for the people she loves, her family, and those who are sick. “If a Mass was not ongoing, I would pray the Rosary, which I discovered to be meditative and calming. I would leave the church with good feelings,” she says.

Raena adds that visiting the church was also a way to appreciate the architecture, art and craftsmanship of the locals who built them as well as the statues and stories attached to them, many of which are miraculous. Among the most notable devotional objects she was able to see was the Black Crucified Christ (Santo Cristo Milagroso) at the Minor Basilica of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino in Sinait, Ilocos Sur. In Vigan, the statue is fondly called Apo Lakay because it was brought there in the 1880s to miraculously end a plague. Every Friday, pilgrims still flock to its shrine.

One impressive architectural structure that Abella managed to enter was that of the St. James the Great Parish Church in Bolinao, Pangasinan, built by the Augustinians in 1609, using black coral stones with eggs as a binding agent. But her favorite church was Our Lady of the Rosary of Manaoag, also in Pangasinan. This was also the favorite church of her grandmother, who passed away two years ago. “I was lucky to arrive a few minutes before it closed,” she says. “By then it was empty and I was able to spend quiet time inside.”

The journey, with its unavoidable hazards, would urge anyone to seek divine protection. Abella considers one of the highest risks she faced was camping at public spaces with strangers. As her trip progressed, she started to pretend that she was traveling with a group. “Solo female travel can be quite dangerous so I have to be smart,” she acknowledges. “I have weapons with me and I’m ready for combat.”

As part of the online audience avidly following Abella’s posts, I witnessed everything from popcorn-munching fascination to nail-biting suspense, with several no-signal cliffhangers. She would periodically go off-grid then pop right back on our feed proclaiming “Day 36! I’m still alive!” Her video camera were at times directed to capture passing scenes from the side window, sometimes toward the windshield to show her entry into another town. I would wonder over the most bizarre sights; At some point, she drove by a boneyard of abandoned vehicles. I would also rejoice when she rewarded herself with simple luxuries, like a car wash in Vigan, or finally using her Negroni cocktail mix in Baler.

Abella successfully completed the first leg, Luzon. She visited Bataan, Botolan, Zambales, Bolinao, La Union, Baguio, Sagada, Benguet, Vigan, Ilocos, Pagudpud, Sta. Ana in Cagayan, Tuguegarao, Isabela and Baler over 38 days. She took a short break in Manila to unload her ambrotypes, restock supplies, and add more equipment. I visited her studio in Antipolo during that period for a quick debrief. It was my first time to see her overland vehicle and some of the finished ambrotypes, all of them astonishing.

While in Manila, Abella loaded a dual battery as her main power source onto the roof of her truck, bought a Claymore electric fan and stuffed her refrigerator with food. The truck was fully serviced. Meanwhile, she attended some family celebrations and one social event, her friends’ photography exhibit, before heading off again. It was her goal to complete the expedition before the rainy season began. “This trip has tested me in every way: mentally, physically, and emotionally,” she says. “I think I’m doing well so far, but I’m just on my first leg. The second one will be tougher!”

Adventures and Misadventures

The landscape visibly changed upon reaching the Visayas. Abella found herself surrounded by fields. The distinct tropical scenery of the sea lay on one side while forested mountains bordered the other. She also had to contend with traversing islands via “roll-on roll-off” (RoRo) multi-deck ships that could carry wheeled cargo. The RoRo ride from the port at Bulalacao was particularly taxing because she was required to board at 10 P.M., but the ship departed late, so she ended up at the port of Caticlan at 3 A.M., leaving her with only four hours of sleep. She found a transient inn near the port. Once rested, she wandered off to watch farmers sort and bundle sacks of onions, that root crop whose prices climbed so high in the Philippines that it is considered a luxury.

At the Pandan Island Resort in Sablayan, Occidental Mindoro, Abella went on an intro dive, bringing her GoPro underwater to capture marine life. She drove by farmers harvesting salt at the flats, scraping them into mounds and heaping them into woven baskets.

She witnessed fishermen hauling their catch to shore at the port of Libas. The fish were pulled in ice-filled buckets to the market, where buyers would inspect them. Aside from fish, the market sold oysters, shrimp and squid. A half order of steamed oysters, two grilled chicken wings, hot rice and an ice cold Coke cost only PHP195. She deemed the meal as “probably the cheapest and most satisfying lunch” she’s ever had.

the Philippines.

Abella rented a boat all to herself going to the famed Gigantes Islands in Iloilo, known for its white sand beaches, stunning rock formations, and long stretches of sandbars. She saw a long line of tourists waiting their turn at the viewpoint called “selfie island.”

Her church stops continued at Iloilo City. Abella visited the National Shrine of Our Lady of the Candles, more popularly known as Jaro Metropolitan Cathedral, which Pope John Paul II visited in 1981. He placed a crown on one of its statues, the Nuestra de Señora de Candelaria, and declared her Patroness of the Western Visayas. The statue, locally believed to be miraculous, is the only female statue among an all-male collection that lines the cathedral’s interiors. In contrast is the Molo Church or Saint Anne Parish, which Raena describes as a “feminist church,” with 16 female saints positioned along the aisle.

From Iloilo, Abella climbed rough and jagged roads to Antique, where she experienced another setback. One of her tires got a flat while at a mountainous area without signal. Some men helped her change the tire.

At Hamtic, Antique, Abella watched fishermen catch bangus (milkfish) fingerlings using bowls and headlamps. “They sell these to fish growers for PHP20 per 100 fingerlings. I’ll never eat bangus the same way again, after knowing the hard work these fishermen put into catching the baby fishes,” she says.

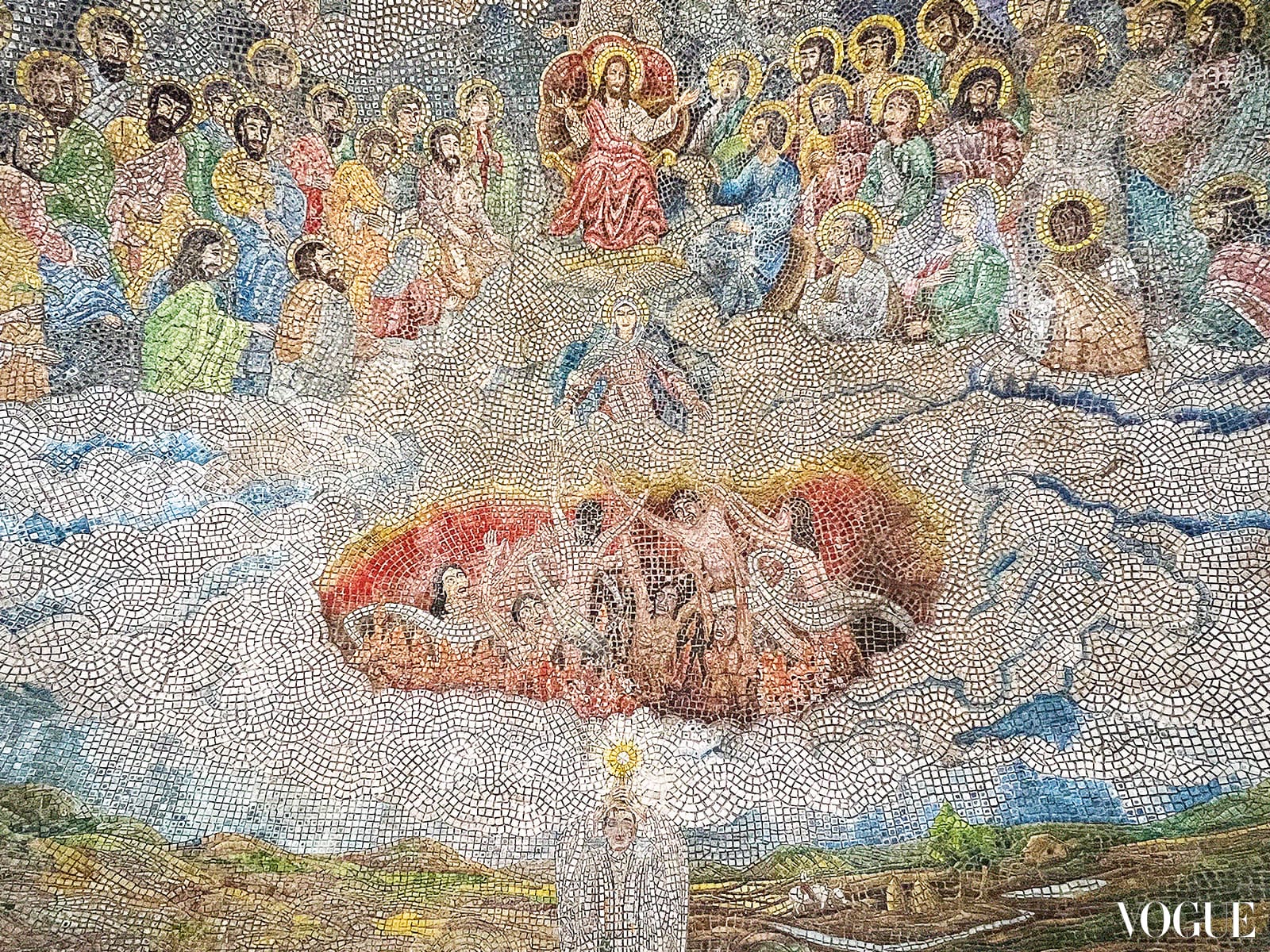

One of the most remarkable churches she visited in the Visayas is the Miag-ao Church in Iloilo. The sculptural relief motifs and ornaments carved on its façade features St. Christopher carrying the Christ Child amid coconut, papaya, and guava shrubs, an example of the indigenized colonial church. Another great one was the San Juan de Sahagun Church in Tigbauan, Iloilo, with its incredible mosaic walls made by a local artisan. “Amazing craftsmanship. At the time these churches were built, there were no heavy equipment, so just imagine the hard labor involved,” she says. “I can’t help but stand in awe of our history and our people.”

Still in Iloilo, Abella visited the studio of artist Didi Kabigting. “Despite a massive stroke several years ago, he still paints every day, even if he is visually and physically impaired. He is only able to see with his right eye and paint with his left hand. That is pure passion and resilience,” she says. Wheelchair bound, Kabigting paints on old reclaimed wood; one of the pieces was formerly a pig’s trough. Abella spent the night at the bed and breakfast of the nearby LS Training Center, which she describes as “a quiet little spot where the owner used recycled and reclaimed materials. The flooring is made of bricks from demolished houses and buildings.” She noticed that one of the oldest bricks was labeled “Yloilo,” which was how the province’s name used to be spelled.

Reunited in Bacolod

Launching its final show for the season, the Fotomoto team traveled to Bacolod. Fotomoto is a photography collective that both Abella and I co-founded. I arrived a week ahead of everyone else to begin a massive installation effort of mounting over 350 photographs, including a series of Abella’s ambrotypes. On the afternoon of the opening, artist Charlie Co invited the Fotomoto team to lunch at his home. As the vehicle I was riding approached his house, Abella’s overland truck came into view, already parked on the street. We were overjoyed that she made it in time for the show.

We had a lively discussion over lunch, joined by Fotomoto photographers Neal Oshima, Veejay Villafranca, Jason Quibilan, E.S.L. Chen, Jonathan Baldonado and AM, Charlie Co and his wife Ann, Art District founder Bong Lopue, Candy Nagrampa of Orange Project, and a very special guest: visiting balikbayan Fernando Afable of Fotobaryo, who will be donating darkroom equipment to the Art District. Abella is a dear friend of Afable. She recounted stories of their time together in New York and the memorable early days of Fotobaryo in Batangas. At the opening reception, we were joined by another Fotomoto co-founder, Sandra Palomar, and some artist friends from Manila and Negros.

After two blissful nights at the Seda hotel, she left the next morning for Don Salvador Benedicto.

Her adventures continued on the way to Sipalay, pausing for fresh oysters along the way. Raena told herself that the goal was to eat oysters every day. At the Sipalay beach, one the cleanest beaches she’d ever seen, she made one of her many sunset timelapses.

Shortly after, Abella began to feel ill. She was late to the Malatapay Wednesday market. By then the livestock trade was almost over. Pigs were loaded onto converted tricycles with cages. She took a video of a man pulling a cow refusing to budge, while another man was whipping it. “Yes I feel very sorry for the animals. But this is the livelihood of the people here. They sell these animals so they can buy food, pay rent, and send their kids to school,” she notes. The market was also selling dried fish and local delicacies like kinilaw na balat, a ceviche of sea cucumber, shellfish, and seaweed, at only PHP20 per order.

As soon as she felt better, Abella took a boat to Apo Island in Dauin and went snorkeling and spotted five huge turtles. She spent the night at Mary’s Homestay where clusters of birds could be seen nesting at the ceiling. “According to Mary, this is the same species of birds that make birds’ nest soup. They refuse to sell the nests, even if they can make money out of them, because they had grown to love the birds and treat them as pets,” she says. Mary told her the story of how when she got sick, the birds followed her to her other house in Apo Island and kept her company until she recovered.

In Panglao Island, Bohol, she stayed at a quiet little Airbnb with a bouldering wall outside her room, which the owner invited her to try. Raena is not new to bouldering; in Manila she sometimes works out by wall climbing.

From the same resort, she took freediving lessons. “Staring down at the unknown vast sea with just a line rope in sight was scary but also meditative,” she reflects. “Unlike other extreme sports that are full of adrenaline, free diving requires the exact opposite mindset. The diver should be calm and relaxed to be able to descend in one full breath. Before descending, I spend a few minutes floating on the water, zone out, focus on my breathing, then dive.”

Raena drove on to Anda and found a little place right at the beach. The ferry rides to Siquijor had been cancelled for the day due to strong winds. Rainy season was slowly creeping in. She was content to enjoy her ocean view for a while with a bottle from Sagada Cellar Door, making it all the way from the beginning of her journey in the mountainous North all the way to the sandy Visayan islands. From her porch, she watched a kite surfer take advantage of the winds.

While lounging, she spotted an all-black tricycle, strange considering tricycles are typically very colorful. She found out that the resort’s Belgian owner, a man named Boris, traveled around the Philippines in that tricycle. He showed her a feature on GMA7 from way back in 2013, so that she would believe him. When she showed Boris her “zombie apocalypse vehicle,” as she calls it, he commented, “Wow, you have everything! You’re like Mary Poppins!” Raena compares her truck to a giant Swiss army knife; it even has a bottle opener attached to it. “My truck looks weird,” she says. “If Martha Stewart, Bear Grills and Frankenstein had a threesome, my truck would be their offspring.”

The people of Siquijor still practice forms of animism and are renowned for it, especially for their healing traditions. Raena visited faith healer Noel Torremocha at Balay Pahauli Healing Hut, located in a small village up in the mountains. The healer covered her from neck to feet in white cloths and made her sit on a wooden chair. Underneath her, he poured an ash-like potion over charcoal, which created plenty of smoke. “They call it pausok,” Raena says, “It’s supposed to get rid of ailments and bad juju. Afterwards he gave me a hilot,” she says, referring to the indigenous energy-manipulating massage that has been practiced since the pre-colonial era. Statues of the Virgin Mary, the Crucified Christ and the Sto. Niño are displayed around Bahay Pahauli. Termed “folk Catholicism,” this distinct combination of animism and religion is practiced all over the Philippines in different ways.

Through Mindanao

Raena entered Mindanao via Iligan, then took the barge at Mukas Port to Ozamis. She visited the National Museum Western-Southern Mindanao in Zambaonga. Located at the historic Fort Pilar founded in 1635, it was declared a National Cultural Treasure in 1973. The museum’s ongoing exhibits include “Filipinas: Photographs by Isa Lorenzo,” Bert Monterona’s large scale paintings, “All-Out Peace Not War/Kalinaw Hindi Digmaan,” and a video by photographer Jacob Maentz, who has been documenting the indigenous peoples of the archipelago. Raena also visited Zamboanga’s Yakan Weaving Village and the Zamboanga Canelan Barter market, which sells plenty of packaged snacks from nearby Malaysia.

She drove through Pagadian, Sultan Kudarat in Maguindanao, and Cotabato City. In Cotabato she visited the second largest mosque in the country, called the Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah Grand Mosque, funded by the sultan of Brunei. “The area is on red alert because of a recent encounter. A military group is positioned nearby,” she tells us. She also visited the Pink Mosque, officially called the Dimaukom Mosque, in Datu Saudi Ampatuan. The mosque was painted pink by the Christian workmen who built it, as a symbol of peace, love, unity and inter-faith brotherhood. Ironically, further down the road is where the Mamasapano massacre occurred.

Raena needed to pass through a number of checkpoints along the highways of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao. “The route from Padagian to Cotabato to GenSan used to be extremely dangerous. Today the area is safer and more controlled,” she says. Along this route, she chose to stop for a break when she chanced upon a group of adventure riders with BMW bikes. They exchanged stories, riding tips and routes. One of the riders, Atty. Gerard Mosquera, a Harvard alumnus, offered her a stay at his Airbnb in GenSan. He just completed the Philippine loop, riding 14 days around the country.

After receiving a tip from a friend, Raena decided to drive back to Cotabato and stay at a typical T’boli house by Lake Sebu. The lake is filled with pink water lilies, making for a scenic drive from there to Glan Saranaggani. She stopped at a quiet cove that is a protected marine sanctuary. There, the community rescues and treats sick sea turtles called pawikan and also protects their eggs. Raena was able to meet the organization’s president, a lady named Amorasola, who let her hold one of the eggs. After a couple of nights, she drove eleven hours, straight through Davao City, and set up camp by the sea at Governor Generoso. There were no other guests at the beach resort, only caretakers. She stayed for three days, snorkeling daily, able to venture alone up to 150 meters from the shoreline, unafraid even when she spotted a sea snake.

From Davao Oriental, she drove to Surigao, and onto the RoRo for Siargao. Her sister joined her there for a few bonding days of leisure and more snorkeling, albeit local corals were still recovering from the devastation of Typhoon Odette. On the fourth of July, Raena finally began the drive back, returning to the Visayas via Southern Leyte. It has been 124 days since the start of her journey. As of this writing, there is no planned date for her return home.

Raena’s voyage is a unique, deeply personal story that we had the privilege of following and recording. Hers is a case of true overlanding: grand adventure, triumph through discomfort, intense communion with nature, localized cultural learning, connecting with people along the route, and ultimately, a meaningful journey that has become greater than herself. A note she sent us midway: “I hope we can inspire readers to get out of their comfort zone to explore and love our beautiful country.”