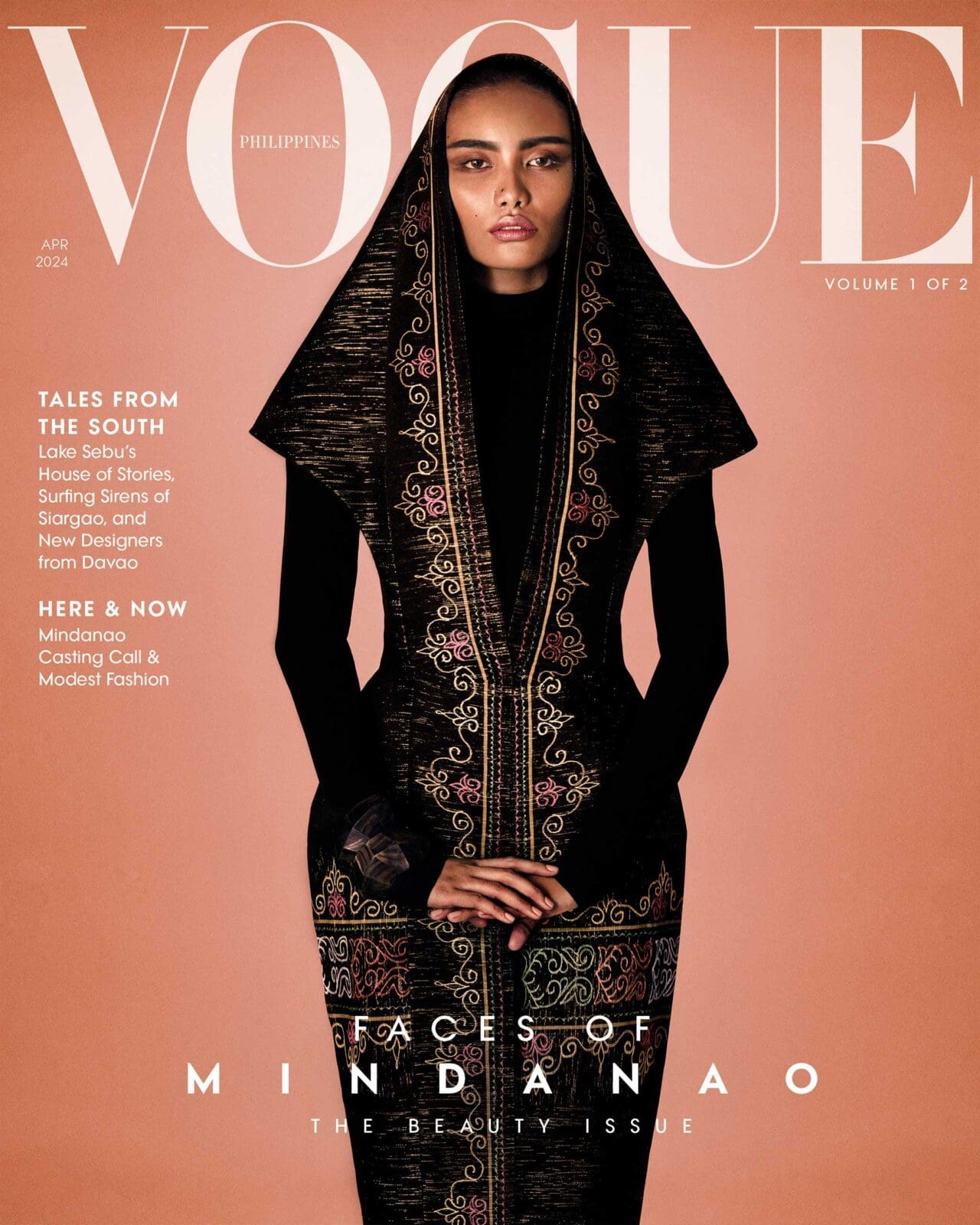

Photograph by Pam Quiñones. Special thanks to Ditas Lobregat of Vista Del Mar Resort, Errold Lim Bayona and Sergio Ilul

The Sama of Southern Mindanao believe in going with the waves; if you want to be with nature, then you have to go with nature.

Clouds never settle over open seas. It needs the surface of land large enough, like a small island, for the elements to allow the clouds to stay put a little while longer.

Our tour guide, Errold Bayona, rattles off scientific facts such as these easily on the car ride to the Santa Cruz Islands of Zamboanga City, known all over the world for their pink sand. Tourists who visit love to edit their photos to make the beach look an alien shade of pink on social media, but in reality, the sand is actually a mixture of coralline sediments: red organ pipe corals, white bleached corals, and discarded seashells pulverized by the waves for eons. Up close, it’s easy to pick apart the sparse reds from the greater volume of whites that comprise the signature pinkish tint from afar.

Local tour guides at the city port detail a set of rules before sailing down south. This includes a reminder for visitors to not bring any single-use plastics and a request to not bring any seashells or corals home.

When tourism boomed for the city in the 1960s to the 1980s, foreign tourists flocked to bask in the beaches’ beauty while taking home pieces of coral to use as ornaments. Coupled with coral reef mining and dynamite fishing practices around the reefs, the coral reef population quickly dwindled and the Smaller Santa Cruz island further shrunk in size. At its worst in the early 2000s, the island was small enough that it could almost be swallowed by the sea if the tides were too high.

It’s easy to see why the guides feel the need to remind tourists about their rules as the stretch of the sand bar is dotted with shells and fragments of coral in fascinating shapes and vibrant shades of red. They’re still big enough to hold against the sun and snap a photo. But also, small enough that they’re tempting to keep in your pocket like a charm.

By April 2000, the government declared the two islands and several kilometers surrounding it a marine protected area. With the signing of Proclamation No. 271, measures were taken to safeguard the 1,548 hectares of the marine park. At the local level, this is felt through the locals’ appreciation for what they have and the discipline to take care of it. They adhere to a Sama practice of going with the waves; if you want to be with nature, then you have to go with nature.

With tourism slowly picking up again, visits to Santa Cruz today begin at the larger island containing a sprawling mangrove lagoon. Beside the docks is a small village where people of the Sama group reside. For most of these people living by the sea, more specifically, the Sama-Bajau people, fisheries and tourism have naturally become their livelihood.

Errold enumerates that sub-groups exist within the larger umbrella of the Sama ethnolinguistic group. There are the Sama-Badjau who are the sea dwellers; the Sama-Bangingi who are mostly merchants residing in coastal areas; and the Sama-Dilaut whose trade is both from the land and sea. The three share a similarity in having a hand in the local carrageenan industry which thrives all year round.

Other groups in Zamboanga are the Yakan who hail from Basilan, known for their intricate weaving crafts, the Tausug of Southwest Mindanao who are commonly into agriculture and metallurgy, and the Subanon found in agricultural uplands of Zamboanga del Norte.

Much can be learned about the Zamboanga people by how they care for their land and heritage.

At the islands, the local guides know the stories of their mangroves and the fauna that thrive in the waters well. On the mainland at the city square, the streets are lined with acacia trees that the local government has taken the time to study and carbon date—some of them are centuries old, and so large that you’re unable to wrap your arms around it. Local libraries and museums are still maintained, and even the heritage site of Fort Pilar stands tall thanks to the community who recognizes the value of its proud facade.

“Without us telling our story, you will see our stories [yourself],” Errold explains. Born and raised in the city, he knows that storytelling is an important but sensitive topic for Zamboanga. Now, its reputation in the ‘70s as a tourist attraction has been eclipsed by narratives of conflict in the region.

Efforts to preserve their environment and their culture are important to them because they find themselves subject to this now popular notion about their home. In their own ways, the Zamboangeños resist a singular, prejudiced narrative of their own people through a deeper consciousness of their heritage and nature.

Errold is able to cite more statistics about the islands off the top of his head: At the start of the 2000s, the Smaller Santa Cruz island measured a meager 100 meters in length when it was closed off from visitors. Now from his visits in 2017, they’ve recorded that it stretches out from around 700 to 800 meters—proof that the marine protected area is reaping its benefits.

After the tour of the two islands has finished, our group walks back to the boat. Out in the horizon, the water is a deep shade of blue and wisps of a cloud begin forming up ahead. I think these clouds seemed to have stayed for quite some time that afternoon.