In her latest exhibition “A Tree is Not a Forest,” artist Geraldine Javier explores the storytelling potential of local flora.

We meander along Geraldine Javier’s wild tropical garden, enraptured from every angle. Dragon fruit cacti on our left, fairytale rabbits on our right, a profusion of leaves and flowers everywhere. “Marigolds are the best protectors against insects,” Geraldine says. We pass by a chicken coop. She peeks into the egg catcher and scoops out freshly-laid brown eggs. “The smaller Palawan chickens in the next coop are more suitable for cooking tinola.” Among a copse of trees, she pauses to pick up fallen passionfruit. “I don’t subscribe to the manicured lawn.” Instead, she built a composting area and planted a plentiful variety of local vegetables.

Located in Cuenca, Batangas, Geraldine’s haven has a panoramic view of Mount Maculot, part of the larger geological formation known as the Taal Caldera. Eagles often swoop down from the mountain, attracted to the chickens and rabbits. Owls, bats, and colorful birds also fly about, feeding on insects. All the elements in this place evidently participate in the harmony of life. Earthquakes caused by seismic activity from nearby Taal Volcano occur here so commonly, some lasting 24 hours, that the household members and their pets have grown accustomed to them and sleep right through the tremors.

Geraldine’s art practice is wholly intertwined with her rural studio environment. In 2013, she relocated here with esteemed author, professor, and curator Tony Godfrey. Within a compound of living quarters and studio workshops, Tony built his private encyclopedic art library. That afternoon, he indulged us with a viewing of his enviable print collection and treated us with a browse through dozens of impressive titles, each one expertly classified. Doors and windows are always left open throughout these vine-clad structures. Their 11 dogs and two cats wander freely inside and out.

Since moving here, Geraldine has been working with her local community, training them to be organic farmers and studio assistants. Her goal is to provide them with regular income by finding ways to incorporate their skills into the making of her artworks. “Embroidery is ideal because they can take the textiles home and work on them there,” she tells us. With her team, she also produces functional and decorative art objects, the sales proceeds of which go directly to her workers. Some of these objects are painted furniture, hanging windchimes and artist dolls. To such a degree, both human and non-human relationships surrounding Geraldine are utterly symbiotic.

We enter her studio, perhaps one of the tidiest and most organized in the Philippines. There is a mechanized easel for raising and lowering paintings. With great anticipation, we study her works-in-progress. As of this writing, Geraldine is preparing for a major solo exhibition at Silverlens Manila, running to December 16 of this year. For the show, she is trying something new: experimenting with natural pigments from the plants in her garden. During the pandemic, Geraldine introduced an additional 400 native flora into the property and has spent months sampling many of them for a process called ecoprinting.

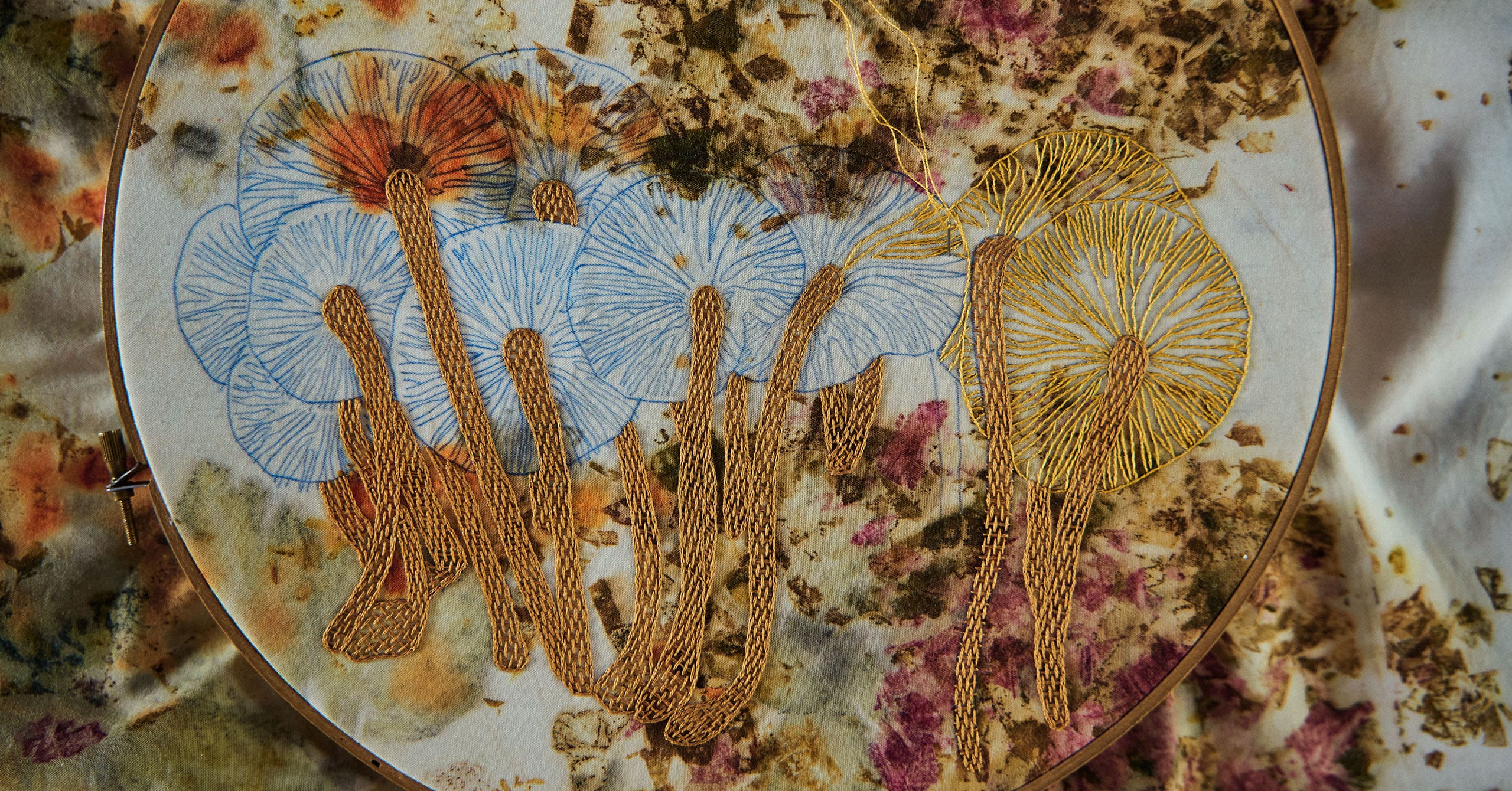

Ecoprints are made by transferring the colors, shapes, and details of leaves and flowers onto fabric or paper. Through steaming, the natural pigments are contact printed onto surfaces, making unique impressions called monotypes. The process is a form of natural dyeing and is therefore environmentally sustainable. Ecoprinting is just one of several techniques that Geraldine employs for her new body of work. One fabric piece might also have, for example, combinations of rust dyeing, indigo dyeing, chlorination, cyanotyping, appliqué, and different styles of embroidery.

We peer more closely at a section of embroidery. Intricate, lace-like patterns depict near life-sized skeleton figures. Before becoming an artist, Geraldine trained as a nurse for five years and has continued her keen interest in anatomical illustrations. The contrast of dainty, exquisite ornamentation to portray a skeleton, the universal symbol for death, is quite astonishing. “I confront the fear of death,” she says, “and accept that after death, we become part of an ecosystem that supports new life.”

In her Life Cycle series, these finely embroidered skeletons are coupled with elaborately embroidered mushrooms, root systems, and the elephant foot yam—a strange-looking plant that used to abound in Geraldine’s property until people came along. Eventually, they disappeared. This led her to wonder if some species cannot co-exist with human presence. Her concern for species extinction extends to a textile installation featuring cyanotype images of endangered animals in the Philippines.

Over a decade ago, Geraldine had already begun to imagine the possibility of hybrid species.New Species in an Anthropocene Era are works on paper that take off from the output of her 2012 residency at the Singapore Tyler Print Institute. Her residency exhibition, Playing God in an Art Lab, presented fictional creatures; hybrids of skeletal parts, flora, and fauna. STPI’s notes state, “While their futuristic anatomy hints at life forms beyond present day, their fossilization simultaneously suggests history and the end of life, echoing both the promise of progress and the inevitability of death. The paradox in these charming blends of botany, zoology, and the whimsical invite viewers to ponder the origins of existence and one’s place in this realm of God’s making.”

While the STPI works consisted of lithography, screen print, and pressed leaves, Geraldine’s current iteration are made with ecoprinted fabric, rust dyeing and embroidery. Tony Godfrey’s essay “Sixteen Creatures in Search of Their Species” likens Geraldine’s hybrid creatures to the fantastical beasts in medieval bestiaries. I would further suggest that they could also be compared to the mysterious plant illustrations in the Voynich Manuscript. To this day, historians, linguists and cryptologists are unable to decipher the manuscript and verify if its richly illustrated plants actually existed. I imagine that archeologists and scholars of the future would also be confounded by Geraldine’s peculiar creatures.

A fantastical hybridization of species is also portrayed in the fabric works Terminator 1 and Terminator 2. Geraldine embroidered human skeletons with wings: one with dragonfly wings, representing the dragonfly as an apex predator, and another with skeletonized leaves attached as wings. On the artist’s penchant for conceiving invented species, Tony writes in the same essay: “Geraldine Javier is both a maker and a storyteller. As a painter, she normally tells—or rather implies—a story; as a maker of fabric works, she is, above all, a maker. Both disciplines are rooted in her early career when she was above all else a collagist—one who made stories, albeit incomplete ones, from scraps.”

Absolute highlights of the Silverlens exhibition are portraits of four historically important naturalists. This is where Geraldine’s material is at its most dense, and the artworks at their most complex and expressive. Portraits of David Attenborough (1926), Maria Sybilla Merian (1647-1717), and Leonard Co (1953-2010) are paintings, rendered in the acrylic and encaustic canvases that the artist is most notable for. Some images are incredibly detailed while others are faint impressions that mark the painting surface. She creates texture on these paintings by etching outlines with the use of a needle. Hints of gold powder provide lush, shimmery effects. This motley of materials and techniques converge in hauntingly beautiful, masterfully composed paintings. The fourth piece, a fabric work with multiple treatments, is equally compelling: a lively triple portrait of Jane Goodall (1934) in field action.

Geraldine’s portrait of Goodall is a respectful and sensitive portrayal of the primatologist at what she does best: closely interacting with her beloved apes. Goodall is legendary for her groundbreaking discoveries on the behaviors of chimpanzees. Her life’s work changed the way we think about the hierarchy of the animal kingdom. Two centuries before her, pioneering etymologist Maria Sybilla Merian was credited for both her observations on insect metamorphosis and for the artistic beauty of her scientific illustrations. At age 52, in the year 1699, she sailed from Europe to the Dutch colony of Surinam in South America, a rare and dangerous expedition for women at that time. This is where she made her magnum opus, “Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium” (1705), a landmark work of over 60 engravings and text descriptions of insects with their host plants. Geraldine paints Merian’s portrait along with reproductions of the etymologist’s outstanding scientific illustrations.

“It seems to me that the natural world is the greatest source of excitement; the greatest source of visual beauty; the greatest source of intellectual interest. It is the greatest source of so much in life that makes life worth living,” stated nature documentarian Sir David Attenborough. His contributions as a natural historian and environmental conservationist have been vast and significant throughout an astounding seven-decade career. Several species are named in his honor. These species Geraldine includes in the painting of his portrait.

At the end of 2022, Geraldine participated in Phylogeny of Desire, a group show organized as a tribute to the late Filipino field botanist and plant taxonomist Dr. Leonard Co. He was the foremost authority in local ethnobotany, the study of how people of a particular culture and region make use of indigenous plants. The exhibit was curated by Co’s protégé Ronald Achacoso, an artist, curator of the Pinto Art Museum Arboretum and trustee of the Philippine Native Plants Conservation Society.

Achacoso writes: “Co was a consummate scientist who expressed the need for art in botany and its vital role in curing ‘plant blindness,’ a seemingly contemporary urban malaise. Plant blindness is the inability to see or recognize the presence of plants in our surroundings and our incapacity to acknowledge its invaluable role in our environment.” Geraldine’s work is a superb example of how artists can address plant blindness. For Co’s portrait at the Silverlens exhibit, she adds a list of scientific names from his book Common Medicinal Plants of the Cordillera Region. By doing so, the artist also inadvertently tackles the issue of general science illiteracy in the Philippines.

Most affecting about the evolution of Geraldine’s art is a restlessness with mastery. She sets herself up as a constant beginner by venturing into techniques she has never attempted before. Like the great naturalists, her life is filled with endless wonder and discovery. Responding to illustrious giants in their field becomes both her challenge and her inspiration. Today, arguably in her prime, Geraldine has fully embraced being an artist-farmer, in which reciprocity and interconnectedness define her world.

- Roots and Currents: Daily Malong Connects The Diaspora With Its Indigenous Heritage

- Marikit Santiago Is Painting A Different Picture Of Motherhood

- Back to Buscalan: Apo Whang-Od’s cover story photographer returns for a personal journey

- Bamboo Is The Emerging Textile That Filipino Designers Are Tapping Into Next