Photographed by Francesc Planes

It’s a hot and humid Tuesday afternoon in Venice, and I’m watching the sun set over the Grand Canal through the Gothic windows of Diane von Furstenberg’s apartment, which sits on the first floor of a breathtakingly opulent palazzo. The splendor is a little overwhelming: The walls are lavished with elaborate stucco work and Baroque frescoes, while the ceilings sag with enormous Murano glass chandeliers. Every room is scattered with priceless furniture by the likes of Pierre Paulin and Frank Gehry, and peering through one doorway I even spot a set of Warhol silkscreens of von Furstenberg herself on the wall.

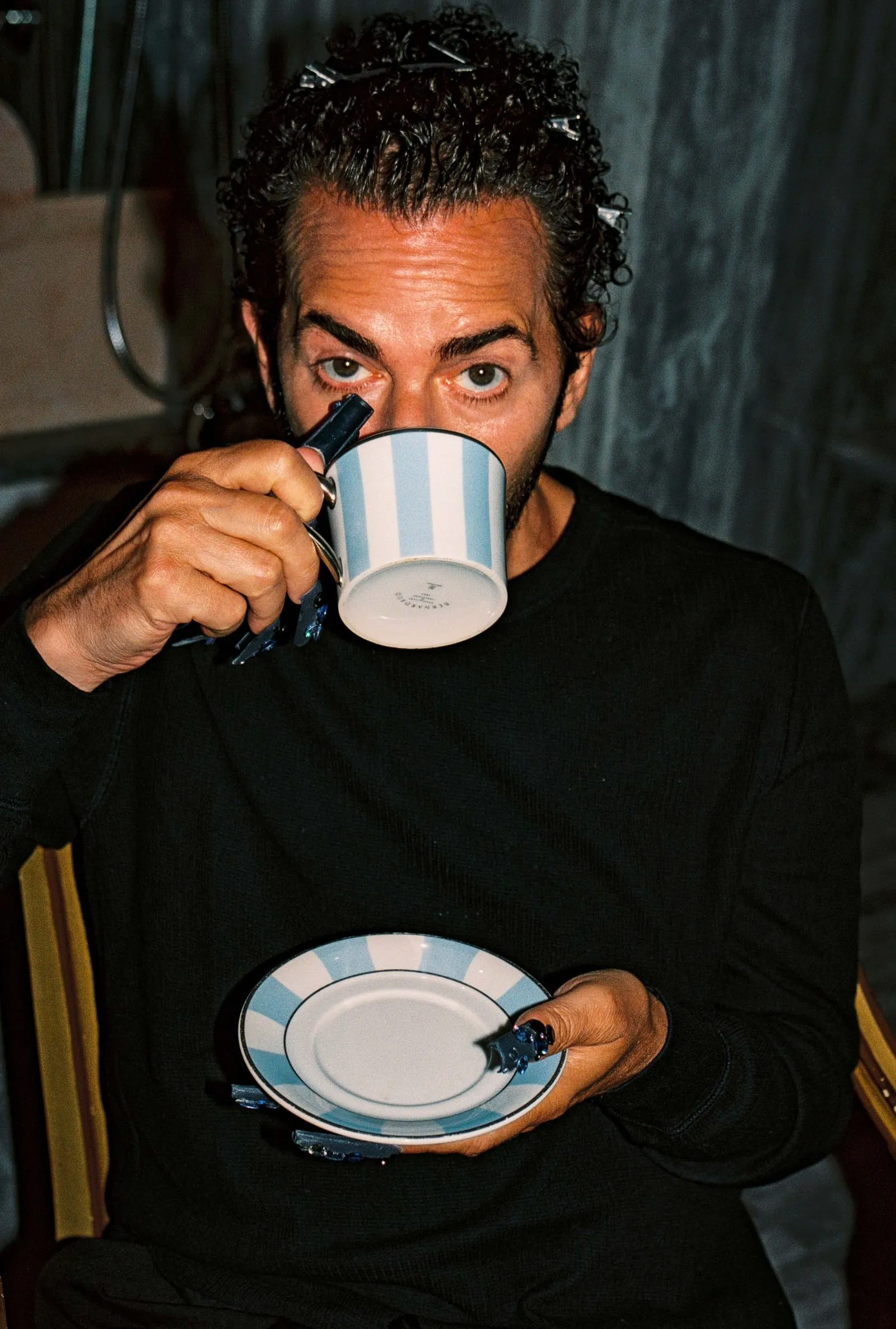

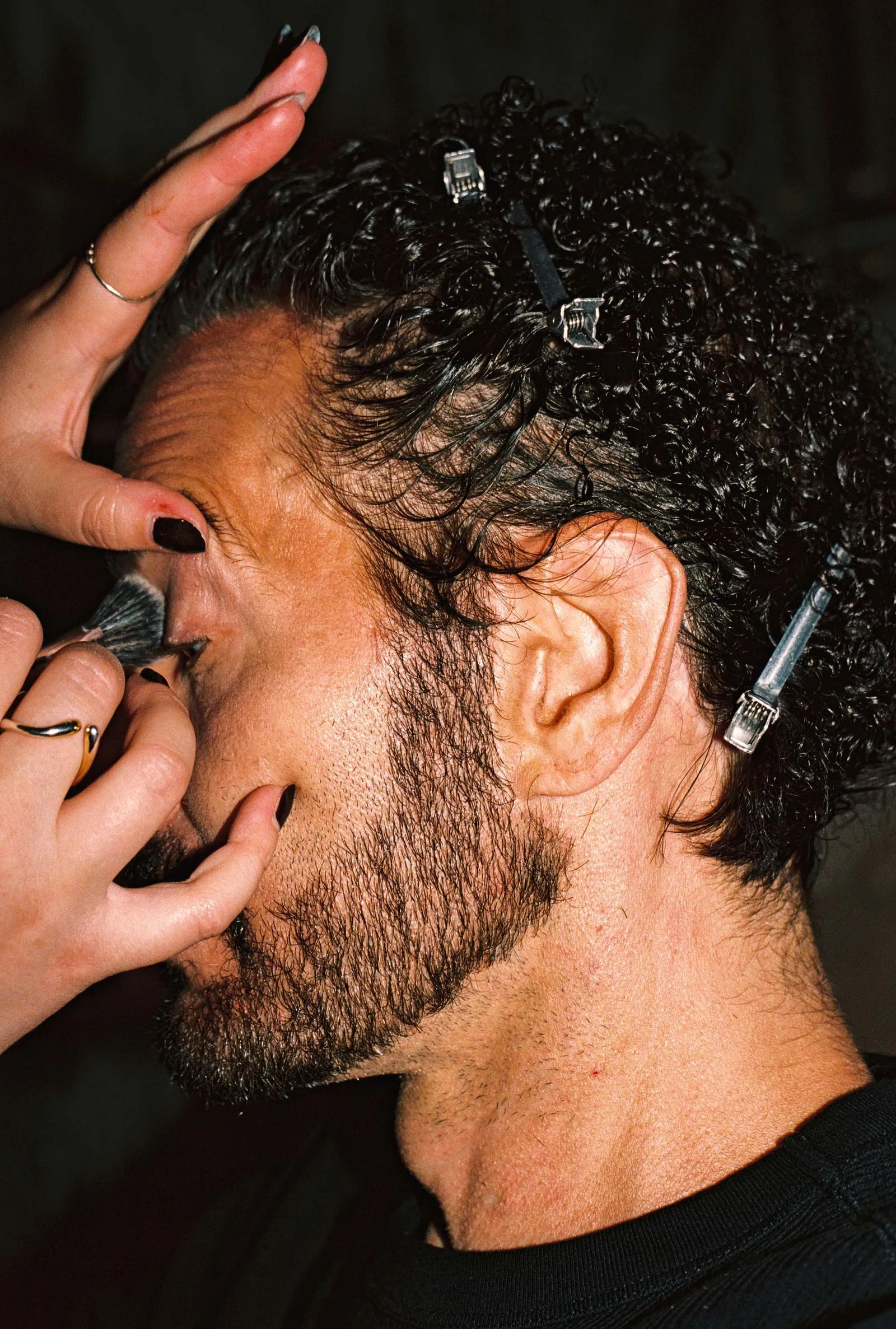

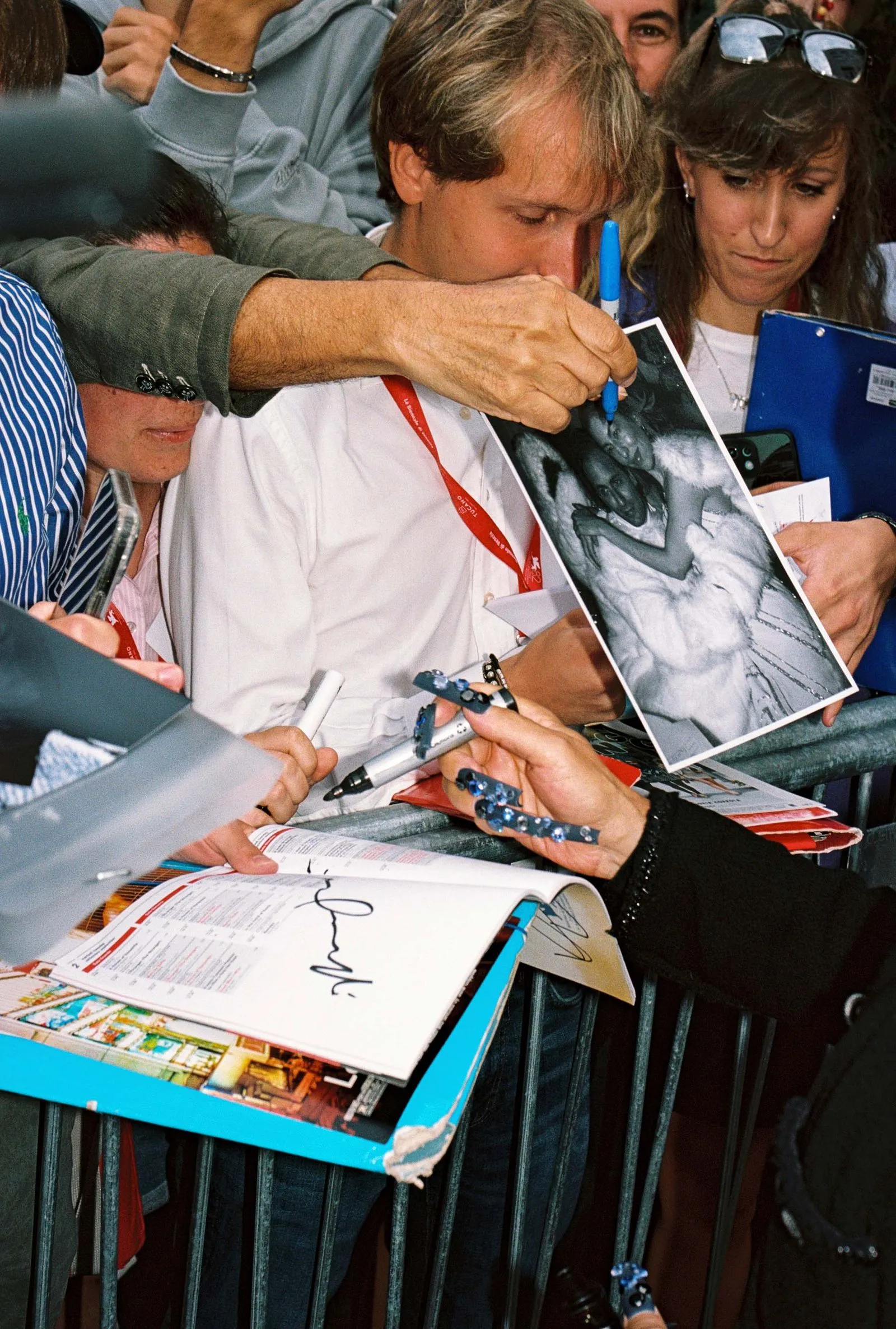

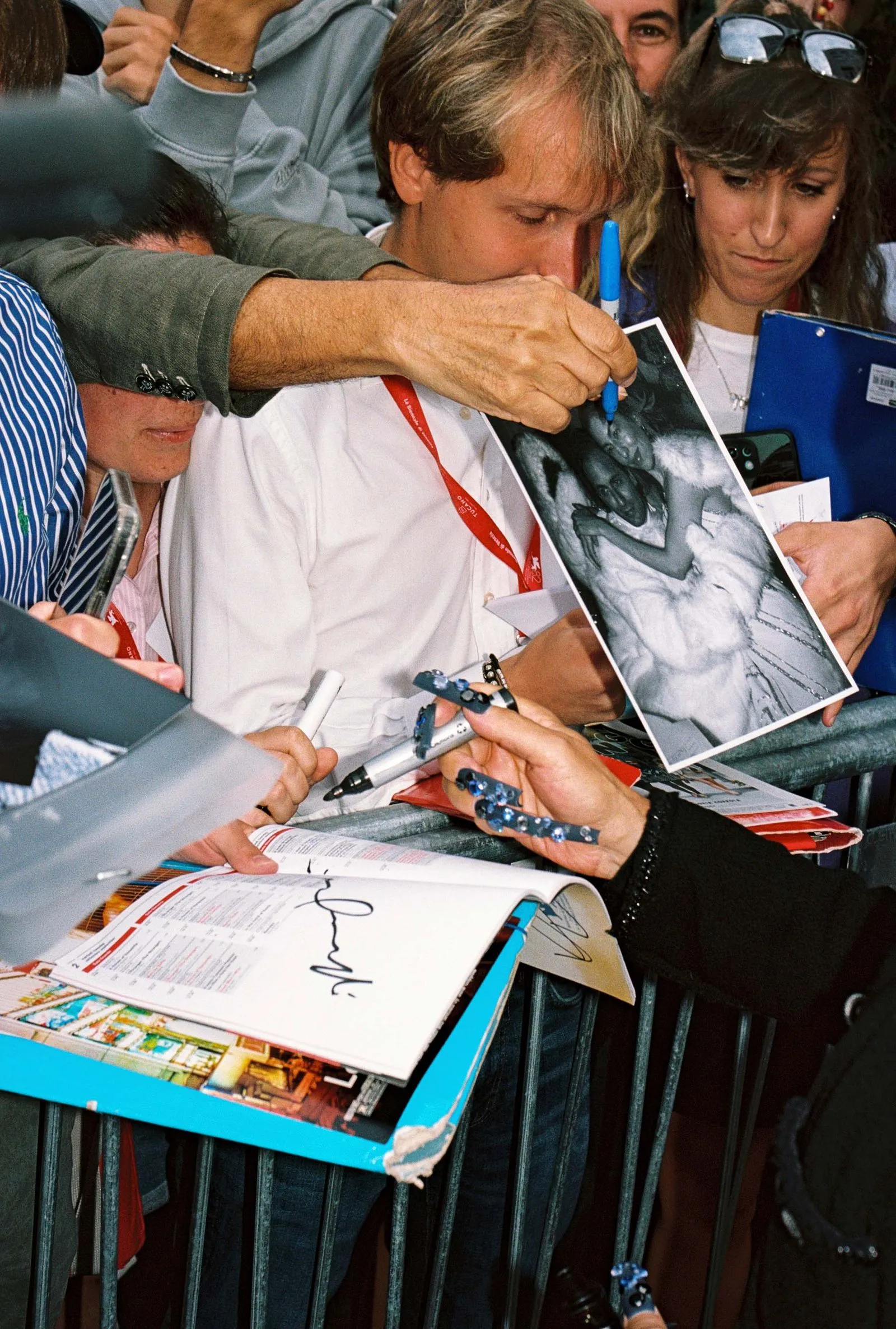

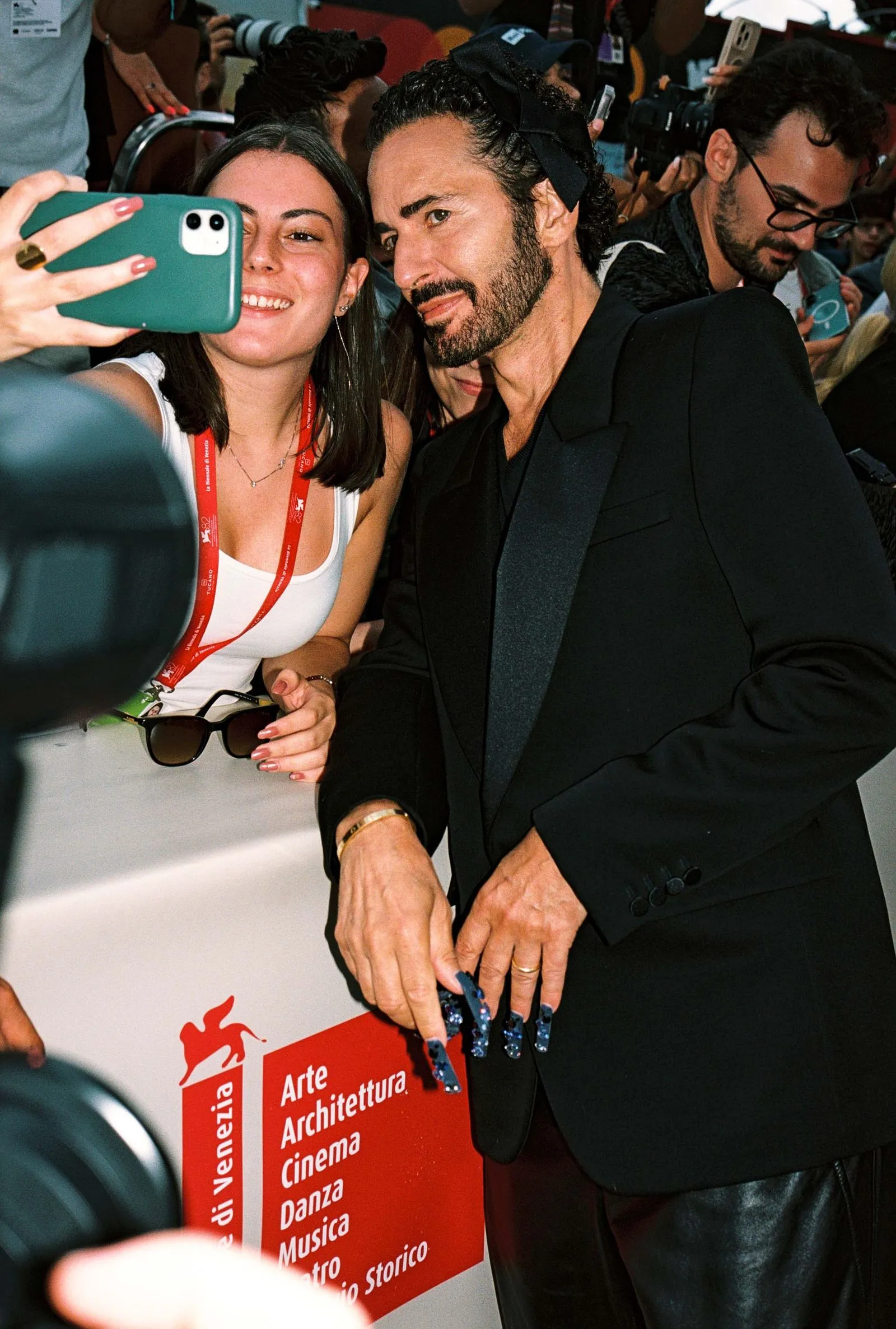

Yet once Marc Jacobs arrives, there’s a new contender for the most arresting detail in the room: his nails. Today, his dazzling, talon-like manicure—blue and black and studded with dozens of rhinestones—serves as an homage to his surroundings. “I thought, What’s going to look good for Venice?” he says, reclining on a plush velvet armchair in a side room. “And I thought black and blue, somehow—like a night sky.” Also worth noting? The grosgrain bow (made by Jacobs himself) placed just so in the parting of Jacobs’s slicked-back hair. “Luckily for me, the great Odile Gilbert was here to do Sofia’s hair, and of course she spent two decades—she’ll remind you—doing the bows in Karl Lagerfeld’s hair for Chanel. I thought, I’m not going to have my grosgrain bow placed by anybody!” Absolutely not.

Of course, there’s a good reason Jacobs is in his finery today: He’s here in Venice for the world premiere of Marc by Sofia, the touching new A24 documentary about the designer directed by his longtime friend Sofia Coppola. After flying in the day before, Jacobs woke up at the Gritti Palace that morning to spend the day preparing for the glitzy afternoon screening—and being trailed by Vogue. He admits he’s feeling a little dazed, thanks to a combination of ferocious jet lag and the circus of attending the premiere, where the film received a standing ovation. Now that he’s at von Furstenberg’s for a more laid-back gathering of friends, he can relax a little. (Well, von Furstenberg’s version of laid-back, anyway, as potatoes topped with caviar are passed around and buckets of Champagne are being poured into colorful Laguna B glassware.)

While his gowns may have walked the red carpets of the Palazzo del Cinemà many times before, it’s Jacobs’s first time attending the festival. “I was a bit apprehensive about coming, to be honest,” he says, fiddling with the silver vape in his hand. “For someone who’s not part of this world and who’s never done film festivals, I was just like, ‘It sounds really scary. How will we be judged?’”

Given the rapturous response at the premiere, are his fears now assuaged? “I mean, it felt genuine. I am a doubting Thomas, and I always think, Did they really like it? But I felt good. I felt good because Sofia seemed really happy, and I felt good sitting next to her and watching it.” (The pair spent the morning hanging out together—with Jacobs dressing her for the event in a custom gown, naturally.)

You could ascribe Jacobs’s nervousness, at least in part, to the fact that the film isn’t just a by-the-numbers documentary covering all the beats of his life and career. It’s more of a kinetic, kaleidoscopic collage: of his memories of being dazzled by the glamour at his parents’ offices at the William Morris Agency; of the shock waves his seminal grunge-inspired collection for Perry Ellis sent through the fashion industry; of his agenda-setting tenure at Louis Vuitton, where, through his collaborations with artists like Stephen Sprouse and Takashi Murakami, he ushered in the collision of high fashion with pop culture that has never since abated. In one memorable moment, Jacobs talks about how his approach to design is not linear—a spirit that’s reflected in the rhythm of Coppola’s film.

Interwoven with classic talking heads are snippets from some of Jacobs’s favorite films (from The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant to The Graduate to Hello, Dolly!), and at one point there’s even a montage recalling the “I Want Candy” shopping scenes of Marie Antoinette—except with Blondie’s “Heart of Glass” playing over swatches of fabric being rifled through by Jacobs’s design team while crafting a new collection. (Coppola also appears throughout, whether she’s striking the clapboard or asking softly spoken questions from behind the lens—making the film partly a portrait of their friendship too.)

It all began—as Jacobs’s husband, Char Defrancesco, reminds him lounging across a nearby daybed—when R. J. Cutler, the director of The September Issue and Martha, approached Mark about the idea a few years back. Given the popularity of fashion documentaries over the past decade—and Jacobs’s humor and charisma—it’s really a surprise it hadn’t happened sooner, though that was partly due to the designer’s own hesitance. “Usually I’d be like, ‘I don’t want to do that. It’s going to be embarrassing!’”

Then Cutler suggested that Coppola was keen to be involved. “I was like, ‘Okay, well, I can’t say no to Sofia,’” Jacobs remembers. “If I was ever going to feel comfortable about this, it would be because she was involved.”

Jacobs’s reluctance to participate in a documentary prior to that point may have had something to do with the fact that, as a designer, he’s conditioned to constantly look forward—to the next show, the next event, the next campaign. “I could very easily fall into the trap of talking about the glory days and how great it was and what a wonderful time it was, because I do have a lot of incredible memories,” he says. “It still takes effort for me not to get stuck thinking about that, and to look at it and say, ‘Yeah, that was great. That was so cool. But that was then, and this is now, so let’s move on.’”

Given the film’s throwbacks to the ’90s—including a segment on the X-Girl guerrilla fashion show, designed by Kim Gordon, coproduced by Coppola and Spike Jonze, and modeled by Chloë Sevigny, among others—it serves as a delightful time capsule of a rare moment of creative cross-pollination. Does he still find that excitement in the young artists and musicians and actors he collaborates with today? “It was part of being that age at that time in that place, and New York was a tiny place,” he says. “It was just so, so different. I’m sure similar things exist today, but I’m no longer a 25- or 30-year-old.” Instead, he says, he relies on Defrancesco and Ava Nirui, the creative director of his youth-culture-focused diffusion line, Heaven, to stay plugged in. “Charly’s 20 years younger than me, and I remember he first played me a Doechii track a few years ago, and I was like, ‘Oh yeah, this is really cool.’ Then fast-forward a few years and everybody’s talking about Doechii. If we were talking about me at a younger age, I would’ve seen it already. You know what I mean? It’s just different.” (That said, I do spy a Labubu on Jacobs’s Hermès Kelly bag, resting on a side table.)

It’s this openness about the long and winding road of a creative life that makes Jacobs such an endearing presence onscreen, even in some of the film’s more vulnerable moments. At one point, he talks about his tendency to compare himself unfavorably to other designers. It was a throwaway comment that felt surprising to me, I say, given that his enthusiastic willingness to cheerlead for his fellow designers on Instagram—where he regularly posts fit pics of himself in Anthony Vaccarello’s Saint Laurent and Demna’s Balenciaga—is rare and infectious. “I mean, I’ve been in therapy about this for years,” he says with a chuckle. “I don’t want to be looking over my shoulder at something else; I want to really be focused on what I’m doing. But I do tend to do that. I love the work of a lot of other fashion designers because I love being in this field and doing this job. I’ve always loved fashion, and I have no problem saying it. There are other designers, I know, who would die before they’d admit that they looked up to someone else. That’s their path. But I like praising people who do work that I love, and I like wearing their clothes, and I like shopping for their clothes and watching to see what their next show’s like. That’s just me.”

What the film also captures brilliantly, however, is Jacobs’s distinctive genius as a designer. One thrilling section charts the run-up to his spring 2024 show, which memorably featured an oversized folding chair and table by the artist Robert Therrien, under which models processed with Diana Ross–on–acid wigs and deliberately clumpy fake eyelashes. After absorbing Jacobs’s melting pot of references throughout the film, we can finally appreciate how he distills them into clothes that read a little strange at first—the proportions of the paper doll coats, the blown-up handbags, the oversized paillettes and trompe l’oeil embellishments—and then, just as quickly, become strangely desirable.

But perhaps the most affecting moment in the film comes the day after the show, when Coppola travels to Jacobs’s Frank Lloyd Wright–designed home in upstate New York, and he greets her in a silk dressing gown, visibly and audibly drained after the previous day’s extravaganza. There’s a great turn of phrase that Jacobs uses to describe a feeling of exhaustion that is not quite postpartum, but “post-art-done,” a term passed on to him by the director Lana Wachowski.

Did he feel nervous about showing that side of the process too? Not just the frenzy and the fabulousness of the fashion show, but the emotional comedown afterwards? “Sofia didn’t overstate any of it. I think neither of us had a real plan—it all just kind of happened. And because of the ease of our friendship, that ended up in the film. Also, that wasn’t even the worst ‘post-art-done’ I’ve ever suffered. He knows, he’s been through them all with me,” he says, gesturing to Defrancesco. “I said it to Sofia a couple of weeks ago. I was like, ‘Thank God it was that show you came to.’ Because even though there were some hiccups, none of them were so dramatic that I was like, ‘This is the end of my life. I’ll never work again.’ I happen to really love that show.”

By now the jet lag is kicking in, and it’s time to let Jacobs—and his Balenciaga ballet slippers—return to the party. (The following day, he’s planning a lie-in followed by a visit to the Peggy Guggenheim, one of his favorite Venice rituals, along with shopping for jewelry at Codognato and stopping for a bite to eat at Harry’s Bar.) There’s one point in the film, I note, in which he describes the thrill he gets from staging his runway spectaculars as akin to the high of being a theater director on opening night. Having gone through the process of making this film with Coppola, has it stoked any aspirations for him to direct films himself?

“Hell no!” Jacobs exclaims. “No. I haven’t said this in years, but people would always ask, ‘What would you do if you weren’t a fashion designer?’ I’m like, ‘I am not a frustrated filmmaker. I am not a frustrated architect. I am not a frustrated artist. I’m not….’” He trails off for a moment. “I’m really happy. What I’ve always wanted to do all my life was to be a fashion designer and to keep making collections. I really have absolutely no dream of doing anything else.”

This article was originally published on Vogue.com.

- A First Look At Sofia Coppola’s Deeply Personal New Book

- A Taxonomy of Sofia Coppola and Marc Jacobs’ Friendship, in Honor of Her Upcoming Documentary ‘Marc by Sofia’

- Couture Week Opens With a Cinematic Bal d’Été, Directed by Sofia Coppola at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs

- The Vogue Review: Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla Is A Worthy Successor To Marie Antoinette