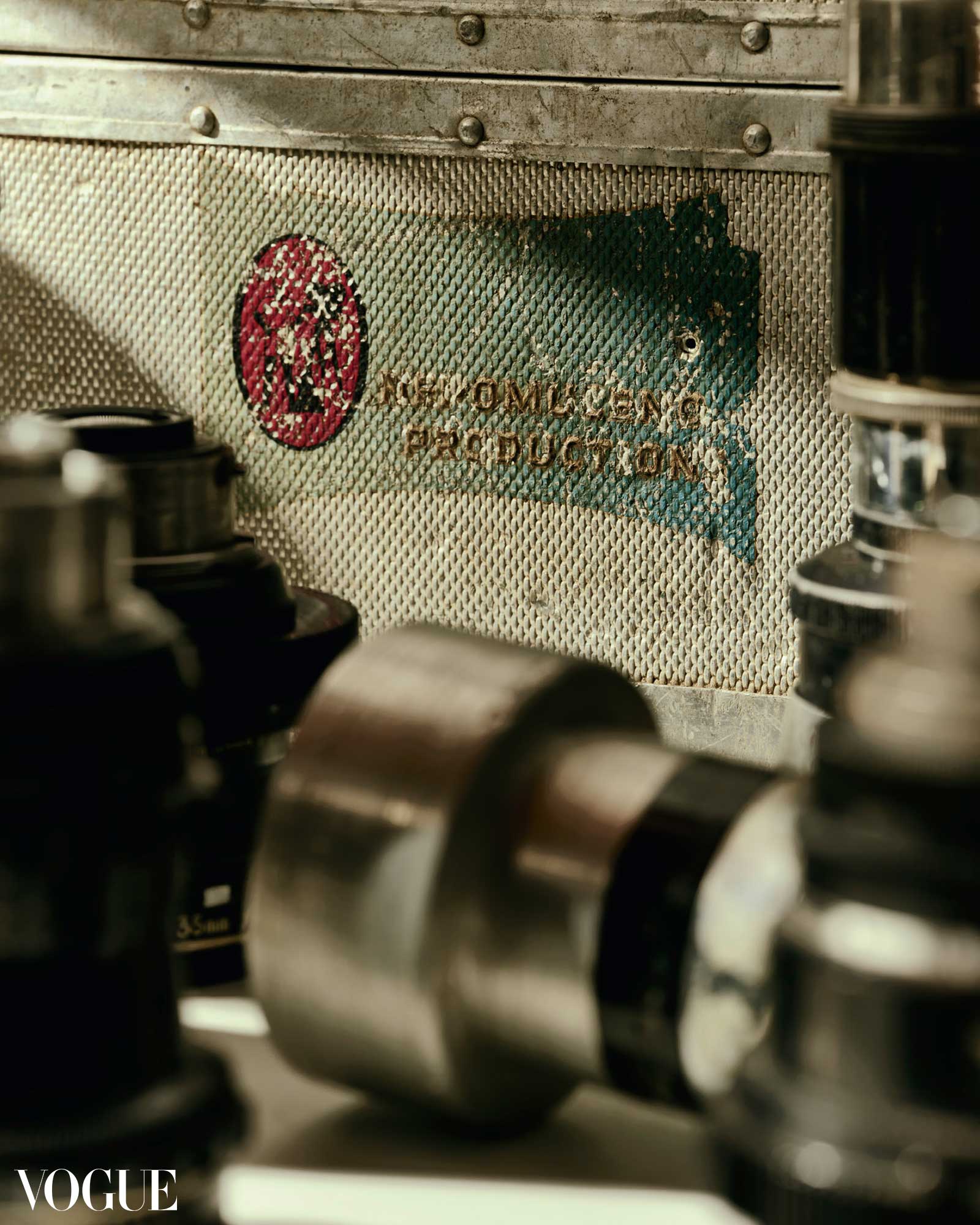

Photographed by Artu Nepomuceno for the August 2024 Issue of Vogue Philippines

Photographer Artu Nepomuceno’s discipline is rooted in philosophies passed on from generations before him; Philippine cinema greats Jose and Luis Nepomuceno found beauty in the details, where light met shadowed edges.

There’s a story that film producer Luis Nepomuceno liked to tell his grandchildren from the height of his career: He once served as a middleman for an American production team filming a project at the same time his own production studio was working on a film as well. One day, while the Americans were lugging around heavy mirror light reflectors the size of refrigerators, he breezed past them with his crew carrying the most feather-light reflector—a smug moment that showed his ingenuity as an experienced Filipino filmmaker.

A young Artu Nepomuceno, his grandson, asked what the reflector was made of, and Luis told him his crafty secret. He peeled off foil from empty cigarette packets and glued them on simple illustration boards for a D-I-Y reflector that accomplished the same job as the industrial-grade film reflectors for a fraction of the price.

Artu says that his grandfather Luis was always telling stories like this. And among the many stories he has told, the one defining story of his career also happens to be the first Filipino film in theaters to be shot in technicolor, Dahil Sa Isang Bulaklak, released in 1967.

The film follows a romantic drama starring Charito Solis and Ric Rodrigo, beginning with the bashful first blushes of courtship between their two main characters, the trials that test their relationship spanning decades, and a gripping ending with all the markers of a classic melodrama of the time. In that year, the film was selected as the country’s entry for the Best Foreign Language Film category at the 40th Academy Awards, but fell short of being accepted as a nominee.

From that film, Luis continued to carve his own name in the film industry with Igorota, Ang Langit Sa Lupa, and a bevy of other feature-length and short films that have inspired younger generations of filmmakers today.

Luis’ diligence and creativity saw him through his long career in filmmaking. “He didn’t care about [winning awards],” Artu says about his grandfather. “He cared about doing work. He cared about telling the stories. The reward was the work itself and that’s what mattered to him. He was obsessed with [making films] so profoundly, a beautiful obsession.”

Dahil Sa Isang Bulaklak was written by Luis’ father Jose Zialcita Nepomuceno, also dubbed the “Father of Philippine Cinema.” The script was the older filmmaker’s masterpiece, though he never made it himself because he was adamant about it being produced in cinema’s latest breakthrough at the time: in DeLuxe Color.

Jose Nepomuceno earned his place in Philippine history through Dalagang Bukid, the first full-length Filipino feature film. It was a silent film in black and white, based on a zarzuela that was popular during the early 1900s. Most if not all of Jose Nepomuceno’s films are lost, including Dalagang Bukid. Nitrate film is a volatile art medium for storage, notorious for spontaneously combusting without enough ventilation. After his filmography grew, the family’s office studio burned down three times, leaving almost nothing to salvage.

However, a study about the filmmaker published at the University of Stockholm attempted to piece together his filmography based on the impressions it has left, found through newspaper articles on microfilm from various Manila archives. At the time when all Filipino filmmaking was independent, the research found that he captured Filipino life as he knew it, making films about what he knew best: his hometown of Quiapo, Christian themes, and love stories, just as in the zarzuelas and moro-moros of that era.

Jose Nepomuceno made silent films from 1919 to 1933 before passing away in 1959. From what the study could find, his work kept record of what made him Filipino during the period of American occupation and colonial rule. “The films of Nepomuceno helped in spreading the Tagalog culture and language to other parts of the Philippines,” the paper reads.

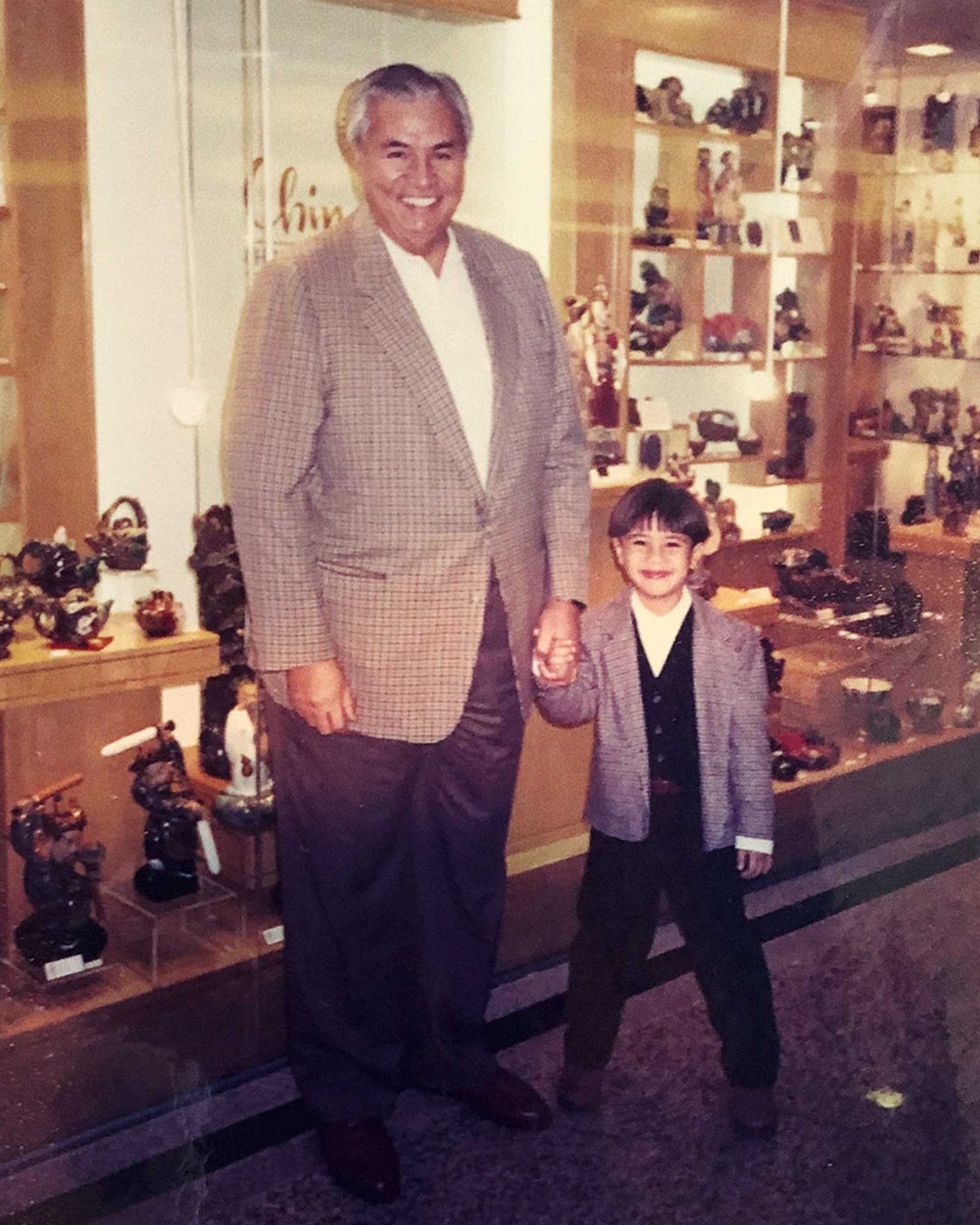

From an old long conversation Artu managed to record while his grandfather was still alive, Luis shared in his own words how he started in filmmaking. “I was chosen by him,” Luis remembers. As the seventh child in the family, he was surprised that his father took him under his wing at the age of sixteen. “Apparently he must’ve seen something in me; that I was curious. It must’ve been a relief to him.” Finally—someone in the family to inherit his work, Luis guessed his father must have been thinking.

Behind many of his father’s films, Luis worked as an editor, a cameraman, or any job that his help was needed in. He was an apprentice for his father for thirteen years before his passing. And similarly, as Luis cemented his reputation as a respected filmmaker, he took his own children and even his grandchildren as apprentices through the stories he shared and the time he spent with them.

The film producer loved taking long drives around the city and sometimes he would take his grandchildren with him when they were still young. “Back then, on a dusty morning in EDSA when the light would kind of go through the tunnels, he would kind of point out ‘Why is that happening?’” Artu fondly reminisces.

These moments were quizzes where Luis would ask where the light was coming from and Artu would answer with how the shadows behaved. “It was very intimate but also intimidating, because there was a wrong answer,” he says.

This, and other drawing exercises to trace and study light were like after-school activities for Artu, nurturing in him a subconscious love for light, too. He did not expect to be in the business of telling stories at first but now he finds himself traveling across the Philippines, capturing the country through his lens. Artu also hopes to find it in himself to bring to life one of his grandfather’s scripts to the silver screen one day.

“Right now, until that day comes, I think my responsibility is to just continue telling stories of people, to do what I’m doing as a photographer,” Artu says. “I feel like everything I do, I constantly and unconsciously do things for him.”

When he found himself switching his degree to photography in college, he remembered his grandfather giving him this advice: “In order to be able to tell a story with a thousand images, you have to be able to tell a story with a single image.”