Photographed by Bea Valdes

Through stops and meals around Phnom Penh, from the Rosewood Hotel to Phsar Chas, BEA VALDES feels nostalgia for somewhere she has never been to.

Armed with no expectations, I arrived in Phnom Penh, into the vast expanse that is the Techo International airport, the day after it officially opened. An unexpected architectural marvel of graceful curves layered into ca`vernous domes, illuminated as if lanterns against the late afternoon sky. Families, in their Sunday’s best, were gathered at the mouth of the entrance, admiring the megastructure. Outside, dotting the parking lot, groups were setting up picnic blankets, as they watched the evening descend on the monumental, glowing arches of Techo.

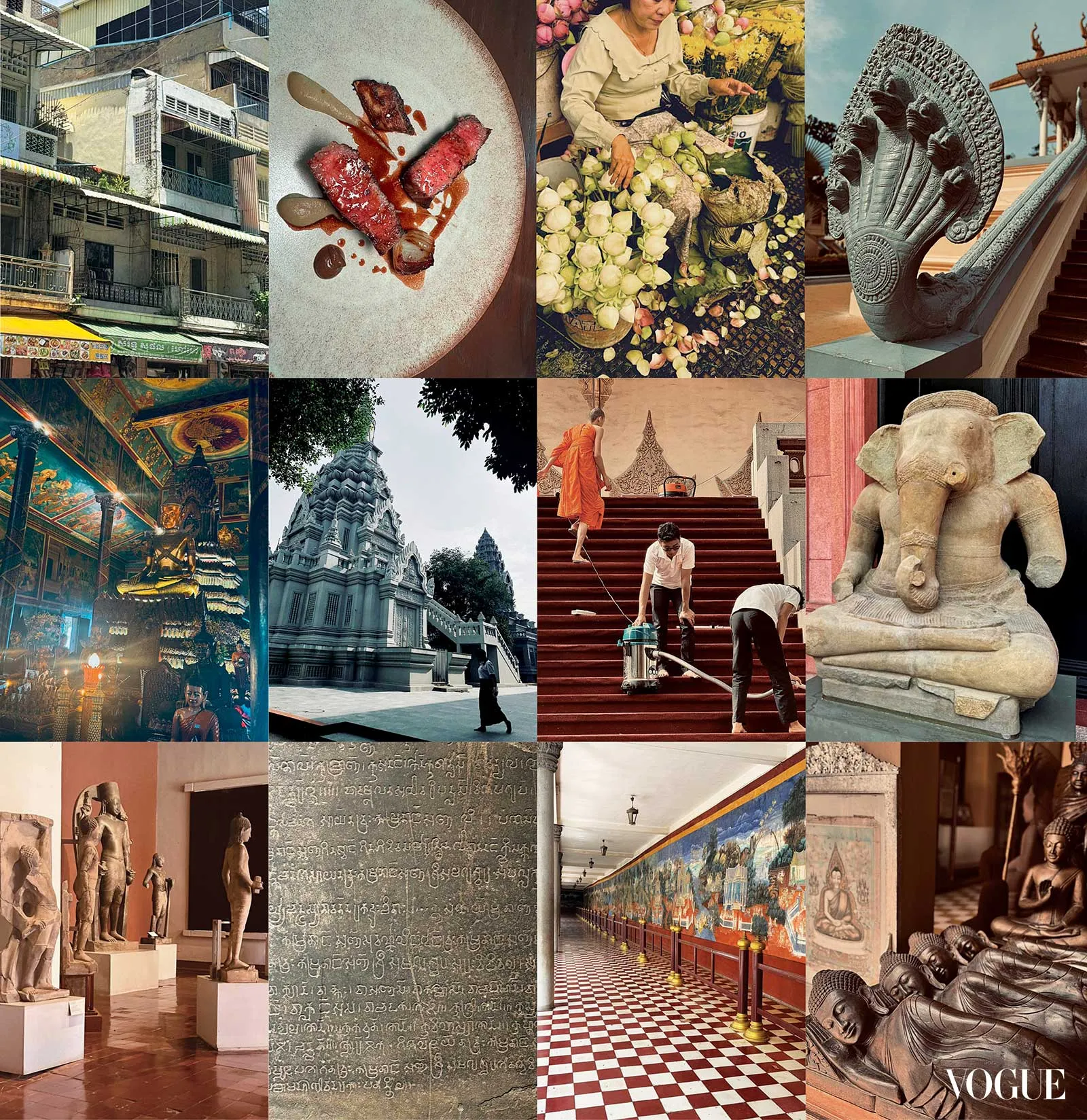

Phnom Penh straddles the familiar and the foreign. As we navigated its neighborhoods, the city revealed layers of both old and new: apartment buildings stacked atop one another, their balconies and grillwork creating a patchwork of motifs that speak to its post-colonial history. The streets unfolded into avenues that, at first glance, felt reminiscent of places I have known. Yet, there was an undeniable difference, an atmosphere shaped not by the cacophony typical of other bustling cities, but by an unexpected calm. The usual hustle of city noises was absent. It seems Buddhist sensibilities permeate Phnom Penh’s urban core.

The mindset of monumentality continued as I reached the Rosewood Hotel. We were received, and ushered into the lobby by an oversized wire sculpture of the Hindu Monkey God, Hanuman, by South Korean artist Park Seung Mo. The hotel, fashioned in discreet tones of cream stone and dark wood, with accents of Cambodian artisanal details, in wicker, wire or pencil shavings, present themselves in a polite, polished manner.

I traveled to Phnom Penh to attend the second edition of the Rosewood Hotel’s culinary festival, “A Taste of Cambodia 2025.” This event served as both an introduction to Khmer culture and an exploration of Cambodia’s evolving culinary identity.

From my room, a view of the city was offered, one where a historic colonial building was flanked by modern structures, with the odd temple engulfed by elder trees. There is a sensibility in the Phnom Penh experience, which encourages an almost nostalgic way of seeing. From the windows of Brasserie Louis, the Rosewood’s bistro offering Cambodian favorites and French fare, we saw the Mekong River and Tonle Sap merge. The seasons dictate whether the rivers flow in the same track, or opposite ways. The direction shifts the Tonle Sap’s waters from brown to blue, creating a tonal contrast between waterways. Convergence seems to happen on many scales here.

At the Rosewood’s newly reopened Nikka whisky bar at the Whisky Library, Manga and mixology collided. One drink offered a combination of cocoa, strawberry, Campari, Cointreau, lemon and cashew. At the adjacent Sora, listed as one of Asia’s 50 best bars, we catch a live band amongst a mix of locals and transplants. Another anticipated event was our dinner at CUTS, and the return of Chef Alexis Moko to helm its kitchen. The multi-awarded steakhouse is renowned for its Mayura Beef. “Chocolate Wagyu,” my Singaporean seatmate whispers. I quickly find out that chocolate is added to the cow’s feed, giving the beef a distinct sweetness.

One afternoon, we were ferried in one of Rosewood’s charming tuk-tuks, to the city’s Central Market. This art deco structure was once Asia’s largest public market. Here, everything from Cambodian trinkets to souvenir tees, to jade bangles to multi-colored miniature buddhas are open for negotiation. A lotus flower vendor, on a stool, surrounded by fresh blossoms, pink and pale green, brushed away the bees that encircled her. She was intent on folding the outer petals into a triangle shape, then piled them into pyramidal offerings.

We wound our way to the Wat Phnom temple, where a pair of massive serpentine balustrades ushered us up the main staircase. Here, the Naga is viewed as a sacred guardian that links celestial realms. At another temple, I opt for a morning blessing. Inside the main hall, ceremonial gold décor filled the walls, the ceilings, the pillars. On an elevated carved bench, sitting in a row, were young monks in their saffron robes. They seemed to be in happy negotiation with a devotee, herself barefoot too. They conversed across gilt, ornamental tables, laden with offerings: A tin tub packed with grapes, oranges, plantains, and dozens of cans of Coca-Cola in intervals. One monk scrolled through his cellphone. Outside the hall, preparations were in full swing, for an upcoming festival. There was the intermittent hum of a vacuum cleaner, working its way up the red carpet.

At the National Museum of Cambodia, there were too many marvels and not enough time. Established in 1920, the museum stands as a monumental repository for Cambodia’s rich archaeological heritage, housing an extensive collection of artifacts crafted from bronze, stone, and ceramics. Among the treasures on display, an exquisitely carved Garuda statue from the 10th century, rendered in sandstone, held my attention. Nearby, impressive representations of Shiva, remarkable for their five heads and 30 arms, dating from the 12th century, captured the intricate artistry and spiritual significance embedded in Khmer sculpture. The museum also featured multiple figures of Ganesh, all worth sitting longer with.

One of the most striking pieces was an inscription found on a broken stone doorjamb, which holds the distinction of containing the earliest known evidence of the “graphical representation of Zero,” dating back to 682/3 AD. I pause before the carved tablet, contemplating the idea of the proof of Zero.

Another evening, we walked through the bustling pathways of the Old Market (Phsar Chas), in the French Quarter, toward the newly opened Pi Sa Old Market Restaurant. Beside the restaurant, a fish monger, cleaver in hand, had shallow vats of live fish, laid out on the pavement. We unfurl in the humidity, as ice cold towels and glasses of even colder champagne made their rounds among us. There is relief from the heat, punctuated by the unmistakable sounds of thrashing and thuds.

We ascended the narrow staircase of the colonial style building into the space of Chef Sothea Seng. As a multi-awarded proponent of Cambodian cuisine, he introduced us to a variety of intriguing dishes. From Ambok rice crusted frog’s legs with avocado guacamole, to pan fried scallop and poached quail egg in preserved duck egg broth with kaffir lime juice, to a tomato Tart Tatin, each plate was delightful in both presentation and delicacy of its flavors.

“There is this rare feeling of wandering, of getting lost in a place, in a sanctuary far from the jostle of crowds.”

Similarly, our four hands dinner at the fine dining Zhan Liang restaurant, with Rosewood Guangzhou’s one Michelin-starred Lingnan House, was a remarkable mix of cuisines. We were served 11 courses of Cambodian, Cantonese, Sichuanese, and Northern Chinese origin. The last dish was coconut pot double boiled peach gum, with American ginseng. A foreign flavor profile, this felt less like a dessert, and more like swimming into a Chinese painting.

In a former textile factory in Phnom Penh, Marco Julia Eggert and Tania Unsworth, originally from Barcelona and the UK, founded Seeker’s Spirits in 2018 to address the lack of quality craft spirits in the region. Their venture resulted in award-winning gin made with 12 native botanicals, such as pandan, Asian lime leaf, Battambang orange, cassia bark, jasmine, and Khmer basil. Their philosophy of “garden to glass,” is best expressed at the actual Seeker’s site, which houses their distillery, a bar, a tasting room, their botanical garden, and an event space. All this, and a disco ball, too.

A single winding brushstroke has become the Seeker’s signature and logo. Tania says it is a tribute to the Mekong River, and the cross-cultural adventures of those who journey across it. We nodded and smiled, as we sipped their gin cocktail. We knew what she meant.

Both the Philippines and Cambodia experience the same rhythm of seasons, alternating periods of rain and of dry weather. There exist other parallels, too, in the traces of a colonial past. Imprints that linger in the architecture, and in the collision of cultural motifs. Buddhist temple pillars, adorned with ornate painting, rise then end in a composite capital. This blend of the recognizable and the distinctive defines the city. Each experience was simultaneously comforting, and novel. I feel nostalgic in this place I have never been to.

Exploring the grounds of the Royal Palace, constructed in the 1860s, on my own, with barely a handful of other tourists in sight, there is this rare feeling of wandering, of getting lost in a place, in a sanctuary far from the jostle of crowds.

Alone, I encountered the epic mural sprawled across the over 600 meters of wall, in the gallery surrounding Silver Pagoda. The painted scenes depict stories from the Reamker, the Khmer version of the Ramayana. In silence, I could examine each character, all the details depicted at length. I discovered that these were painted by students in 1903 to 1904, their names lost in the weathering of time. Across the open courtyard, several Khmer Stupas soaked in the sunshine. In a smaller temple, golden in its quietness, there were multiple wooden Buddhas reclining in rows. There is a sense that they can breathe here. No one else is watching them, but me. And I am only passing through.

Photographs by BEA VALDES. Additional images courtesy of ROSEWOOd