Marikit in her studio. Photographed by Garry Trinh.

Filipina-Australian artist, Marikit Santiago, used to resent her cultural inheritance. That sentiment expressed itself in her work, where she has rewritten biblical references, upended traditional gender roles and expectations of motherhood; and in the process, learned to embrace the duality of her identity.

When Marikit Santiago was a child, she would look to her passport as a source of confirmation of her cultural identity. Right and wrong, left and right, up and down; as children, we tend to only think in the binary, and there, in black and white: “Nationality: Australian.”

“I think, as a child, being Australian was this aspirational concept,” she reflects. “I just desperately wanted to be considered Australian, without question. That meant, at the same time, trying to repress my Filipino identity.”

The daughter of Filipino migrants, living in Sydney’s suburbs, Marikit would rue being the only one of her classmates without a name easily pronounced or spelled; would resent the times she’d have to address her parents in Tagalog around her friends. “Every time my Filipino heritage appeared in my life, it just felt like a burden.” This tension would ultimately bleed into her art practice, for which she found national acclaim, including three years ago, being awarded the Sir John Sulman Prize, one of Australia’s most prestigious for genre painting.

“I’ve always loved drawing and painting, and being creative,” she reflects. We are speaking over Zoom, and behind her peeks the framed paintings by her children, free-flowing and colorful lines moving towards and away from each other. Marikit’s own parents encouraged her to exercise her creativity at home, allowing her to paint murals on bedroom walls, which she’d makeover every couple of years. “I think that’s something that I’ve inherited from my family, and I think it is a Filipino thing. I think Filipinos are very creative, in many ways.”

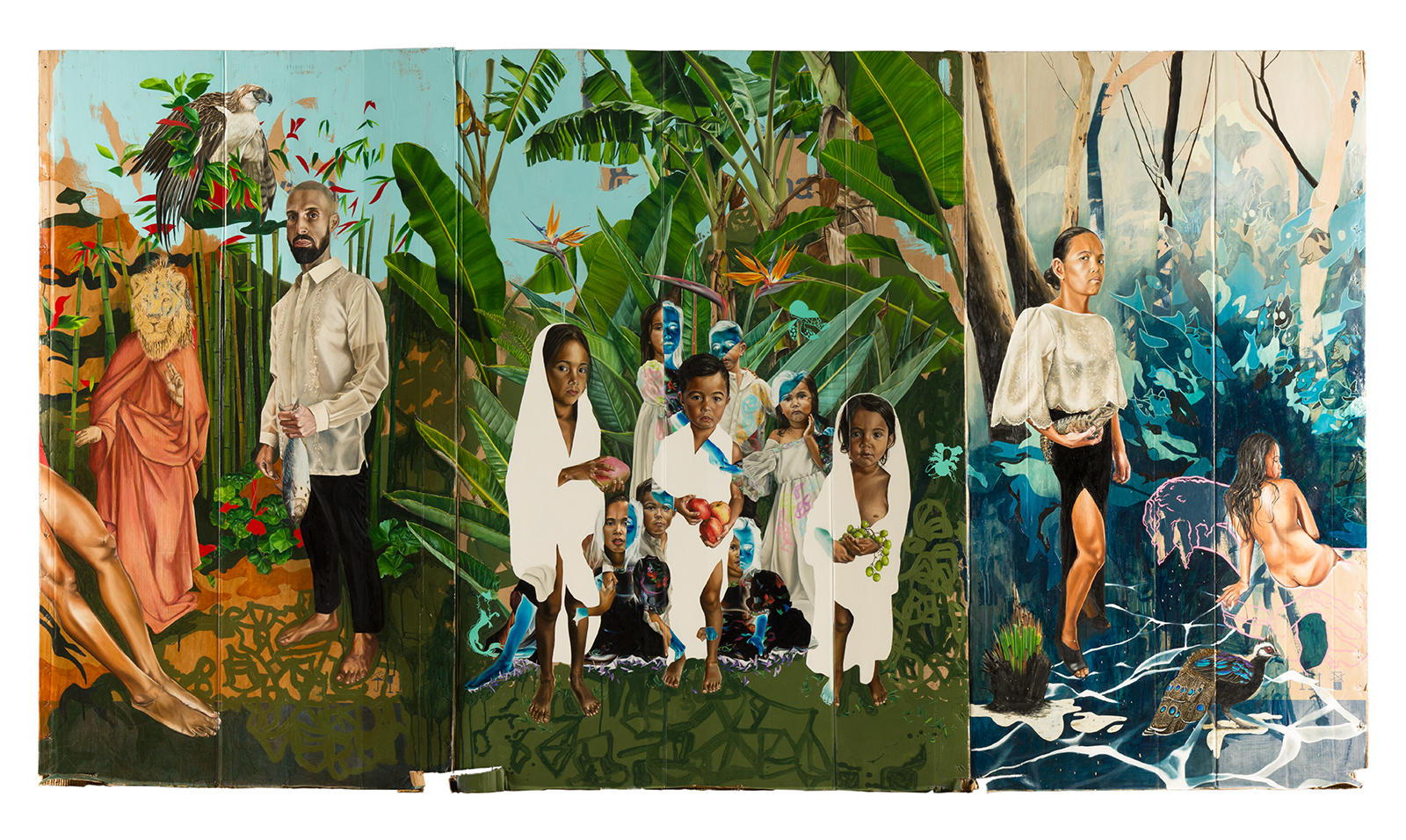

Among the signature identifiers that reveal a Marikit Santiago painting, are the oft-included sketchings and marks left by her three children (she also almost exclusively works on alternative surfaces, like cardboard, as “the migratory experience is already imbued in the surface itself”).“Their marks give visual interest, they make it interesting,” she says. But more than that, she adds, they offer a deeply sentimental and personal aspect that captures a moment in their artistic life. For instance, her eldest daughter Maella first started contributing to works at the age of two; now, as a pre-teen, her organic lines have matured to more precise shading with a paintbrush, and her mother’s artworks act as a time capsule for it all.

She concludes: “If it’s for them, and I’m doing this to help them understand who they are, and understand their multiple identities, then [the artistic process] should include them. And it truly is for them.”

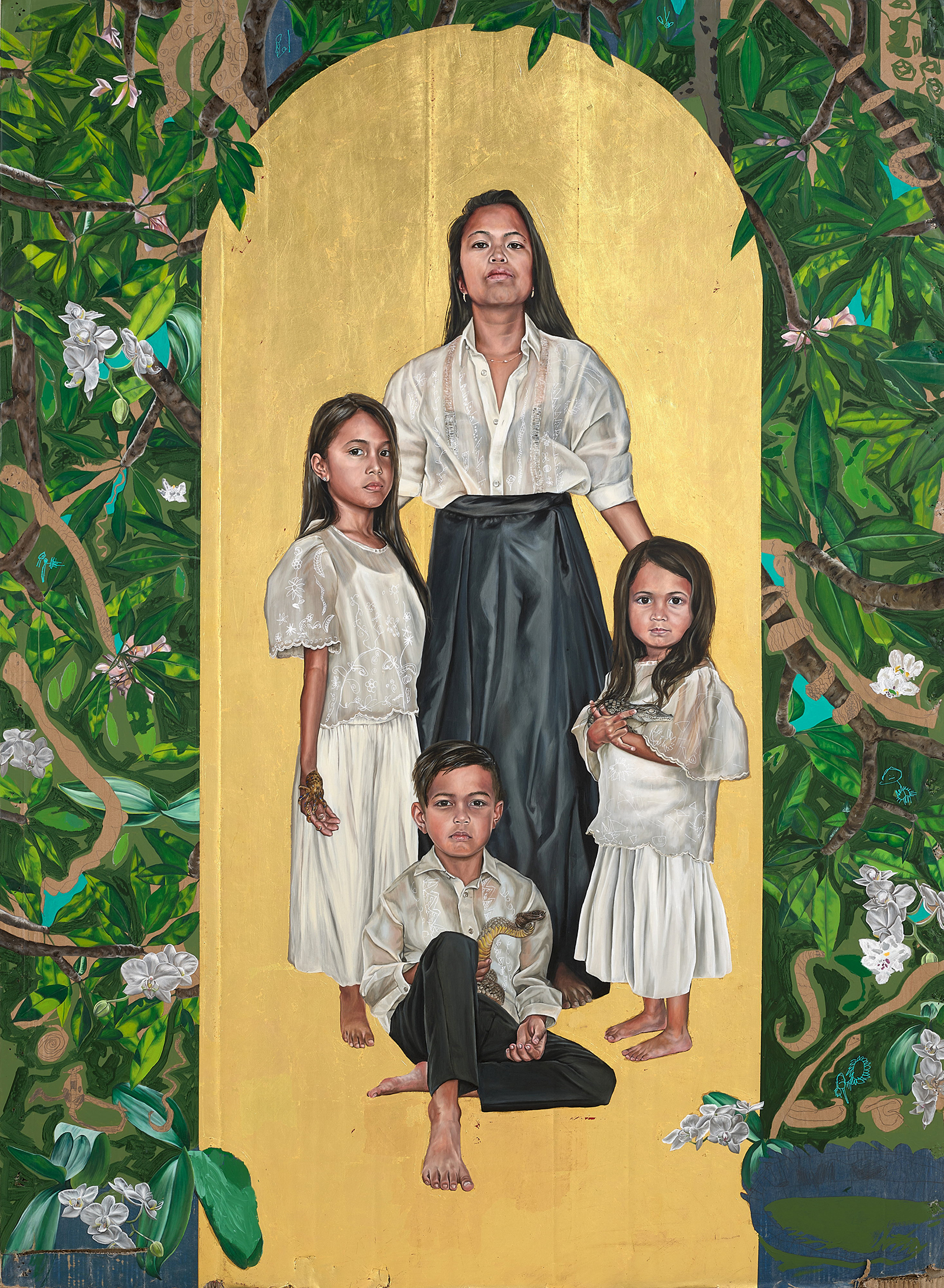

This year marks the third time that Santiago has been selected as a finalist in Australia’s most prestigious portraiture exhibition, the Archibald Prize. This year’s work, Hallowed Be Thy Name, was born of a recent decision by her and her husband, Shawn, to change their children’s surnames to reflect their matriarchal heritage, and continue the Santiago line that would’ve otherwise ended with her and her sister. “I think a lot of Catholicism is innately patriarchal. ‘He’ with a capital H, the Our Father,” she reflects. “I chose Hallowed Be Thy Name, specifically, to reflect how Shawn and I have changed the kids’ surnames, and how it’s a radical stance against patriarchal custom. Our kids are being raised with a lot more Filipino culture, and I wanted their names to signal that cultural upbringing.”

In the artwork, the Santiago children hold their favorite animals. Maella holds a blue-ringed octopus; Santi Mateo, her son, holds an inland taipan; and Sari, her youngest daughter, holds a freshwater crocodile. All native Australian animals; all, most notably, deadly creatures. “What are my children inheriting from me?” Marikit muses. “In the painting, they’re standing in front of me, and I’m putting them forward because I’m confident they can move forward — but they’re holding these animals, and did I give them those animals? Are these deadly creatures passed on from me? Did I put them in harm’s way?”

“They’re holding these animals in a way that it appears they’re at peace with each other. So have I taught my children to tame these threats? That’s the aspiration.” Santiago pauses, before continuing. “But I will always consider, am I just passing my anger on to my kids? When I’m talking about the work I make, and what I’m trying to say with my work, and asking them to participate and consider all these ideas as well, am I just teaching them to be resentful the way I am?”

“I’ll always have that guilt or that will always linger in my mind, even with the good intentions of trying to teach them about themselves. Am I just teaching them to be angry?”

Despite being tipped by many to walk away with the top prize this year, Marikit was ultimately not awarded the Archibald Prize (and life-changing AUD$100,000). The consequence of mining her identities and self-exploration as a means of fueling her art practice — and coming so close, but not winning the Prize—was so devastating that the artist considered this year might be the last she entered. However, it’s impossible not to consider that Marikit’s exploration of her cultural identity, and the roles that her gender imposes on her, has allowed many communities to identify their experiences within her paintings. It’s a responsibility and a privilege she finds overwhelming, but ultimately, pushes her forward.

“That’s why, whenever I enter the Archibald Prize, I will probably always enter with a self-portrait,” she states. The prestige of the Prize draws more attention from the public than mostly any other art exhibition in the country; and it’s to the wider Australian public, and not just the local art community, that she wants the people she represents seen by. “I’m determined to win one day for all the communities I want to represent. To win for women, for mothers, for Western Sydney, for the migrant community,” she says, almost to herself. “Imagine how much more of a win that would be for everyone, and not just me.”

“I just feel like I have so much more at stake, winning with a self-portrait from a person like me,” Marikit concludes.

Some months ago, in the lead up to what will be her first solo exhibition in New York, Marikit’s gallerist sent her an image of La femme damnée, an 1859 painting by Nicolas Octave François Tassaert. The accompanying message simply said, “Perhaps you’d be interested in this.” Translated to “The cursed woman,” a central naked female figure is shown receiving sexual pleasure from three different people. Reports claim the painting’s overt depiction of a woman’s consensual sexual experience ended the French painter’s career. “Obviously, it resonated with me, and I was like, ‘Yep, I’m game to take this on,’” she says, smiling.

In Marikit’s reinterpretation of La femme damnée, the artist positions herself in the place of the central female figure, and her husband assumes the position of all three people surrounding her. It is, without question, the most overtly erotic image Marikit has painted of herself or her husband, and as the day approaches that the painting will be displayed in public, there is undeniably a bit of apprehension. “There’s no confusion about who it is, and what we’re doing. It’s very clear,” she says. Though a painting, it is still their likeness, still their relationship being made vulnerable by public consumption. “But at the same time, why shouldn’t there be a woman of color enjoying sexual pleasure from a man, and where he’s not receiving anything in return?”

She references how historically, women have been the objects of sexual desire—perhaps, particularly, women of color—but consideration has not been given to whether or not they’re consenting, or whether they’re even deserving of that sexual pleasure. Many a painting and sculpture has depicted Leda’s rape by Zeus, in the form of a swan, she points out. How flippantly we are willing to accept art and literature that conveys a man’s sexual desire, regardless of whether or not it is reciprocated. “This work really addresses that, and subverts all those ideas, and states, ‘No, women are just as deserving of sexual desire and pleasure.’”

Now, as an adult and having given herself years of artistic practice to explore her cultural identity, Marikit is still navigating existence in-between two cultures, though her Australianness no longer holds the aspirational quality it once did, and she has found more ease with her Filipino heritage. Unlike the black-and-white attitude she had towards her cultural identity growing up, Marikit is determined her art practice will demonstrate the possibility of nuance to her children.

“I think the biggest thing that I want them to know is that it’s okay to have your different feelings, and if I want to protect them from something that I’ve experienced, I would want to protect them from those feelings of I’ve got to pick one,” she says. In the way that she was once given permission to paint childhood bedroom walls, now she gives her children surfaces to paint that will adorn gallery walls. Including them, for them.“I reflect on that, and I think that was what was most hurtful when I was a kid; that I felt I had to pick one, but the one that I picked, didn’t pick me.”

“So the biggest thing I would want them to learn, if I can put it simply, is nuance. You don’t have to choose, you can be both.”

The painting, Hallowed Be Thy Name, will be exhibited at the Art Gallery of NSW in Sydney until September 3. Her first NYC exhibition, Hallowed Be Thy Name, will show at The Something Machine in Bellport between July 15 and August 31.