Portrait by Hatnim Lee

Rachel Mijares Fick’s scrappy Future Fair has quickly made a name for itself as an agent of change in the New York art scene. But to figure out the way forward, the Filipino-American has looked to her past—to the ancestors and culture that formed her.

The last time I was in Rachel Mijares Fick’s apartment, it was the last weekend of summer and an unexpected downpour had sent a few dozen of her art world friends—from buzzy auction stars to emerging young curators—scurrying for shelter, spiked seltzer and plates of barbecued food in hand.

Mijares Fick and her husband, the artist Aaron Johnson, had invited people over for what was supposed to be a sunny afternoon barbecue on their rooftop, as well as a walk through their apartment, with had recently gone through a rehanging, showcasing the vibrant art collection the pair had acquired through the years. But the best laid plans, as the saying goes, often go awry and instead of an airy rooftop hang, their friends were suddenly elbow-to-elbow, squeezed into the couple’s dining and living areas.

It was imperfect but warm, intimate and somehow serendipitous—symptomatic of what Mijares Fick does in her professional life.

As the co-founder of Future Fair, the New York art fair she launched with Rebeca Laliberte in 2020, Mijares Fick has created a platform that not only champions emerging art players but also brings galleries into its operation in an unprecedented way—offering them a stake in the fair’s growth by making them partners instead of mere exhibitors. In one of the world’s great cultural centers—and one of the most competitive markets for art and art fairs—the four-year-old Future Fair has quickly made a name for itself both for its intentions and its results.

At last year’s edition, there was a line around the block, with many of the fair’s participating galleries already sold out just a few hours into opening day. “It exceeded my own expectations,” she says. The New York Times has called it “pleasantly off-kilter,” saluting the fair’s aim to “serve as a change agent.”

In just four years, Future Fair is already proving a disruptor that can walk the talk. Mijares Fick explains that the fair only makes profits off of ticket sales and sponsorships. “And so that first core group of galleries that took a chance on a new fair, they were honored as being early adopters by being grandfathered into a profit share with us for our first four years,” she says. “We actually didn’t start making profit until last year. And so, they all got a little chunk of money, and they got the option for us to wire that to them so they have that as cash, or they can put it towards their next booth. Or donate it to a fund—which is what most people ended up doing.” That fund is then used to provide more opportunities for voices that typically could not afford to participate in something like Future Fair.

At this year’s edition, for example, the fair had $10,000 that they were able to offer younger galleries in a pay-it-forward fund, allowing them to participate at a lower rate. “So if you were a small gallery and you’re like, ‘All I can afford is this small space,’ now all of a sudden you can have a big space,” Mijares Fick explains.

Of course, the fact that so many galleries choose to donate the amount to the fund speaks to the community Future Fair has created. “They get what we’re doing,” Mijares Fick says. “And we don’t work with a lot of divas. It’s really nice that the fair is clear about who we are, and so the people that aren’t the right fit for us, they leave themselves out.”

“I found myself making art that was so much about creating spaces for people to gather”

Creating Spaces

For about seven years, in her 20s, Mijares Fick worked in various roles at the Volta Art Fair in New York, starting as a fair assistant and growing into a project coordinator and then fair producer. By the time she left Volta, she found herself at a crossroads. And inspired by the Bernie Sanders campaign, she thought about working for a non-profit. “This was at a time when Bernie Sanders was running for president for the first time,” she says, “I was really inspired by his call for people to come together and support each other.” But eventually, she found herself pulled back into the art world—she sensed that there was a hunger for a new kind of fair.

“I kept talking to small business art dealers who were looking for a new fair,” she says. “They wanted something different that didn’t feel as corporate as many of the fairs were, something that felt more similar to and in alignment with the kind of small business that they were running with their artists.”

“I thought, ‘Well, what if we just got together and started our own fair, and you guys would be the stakeholders in this, rather than starting off with big investors behind it?’” The seed for Future Fair was planted.

In school, Mijares Fick studied fine art, thinking she would become an exhibiting artist. “I went into school to study how to be an artist and I found myself making art that was so much about creating spaces for people to gather and have experiences together,” she says.

Today, she says she still considers herself an artist. “I just see the art fair as my medium now. And being an artist, everything you do comes with a lot of intentionality… [At Future Fair] we do a lot of experimentation, but it’s balanced with critical thinking and intentionality.”

Telling new stories

Today, on the cusp of spring, Mijares Fick welcomes me back into the warm, cozy East Williamsburg apartment she shares with her husband and their chihuahuas. As the afternoon light gives way to the evening, she leads me to a painting hanging in their dining area.

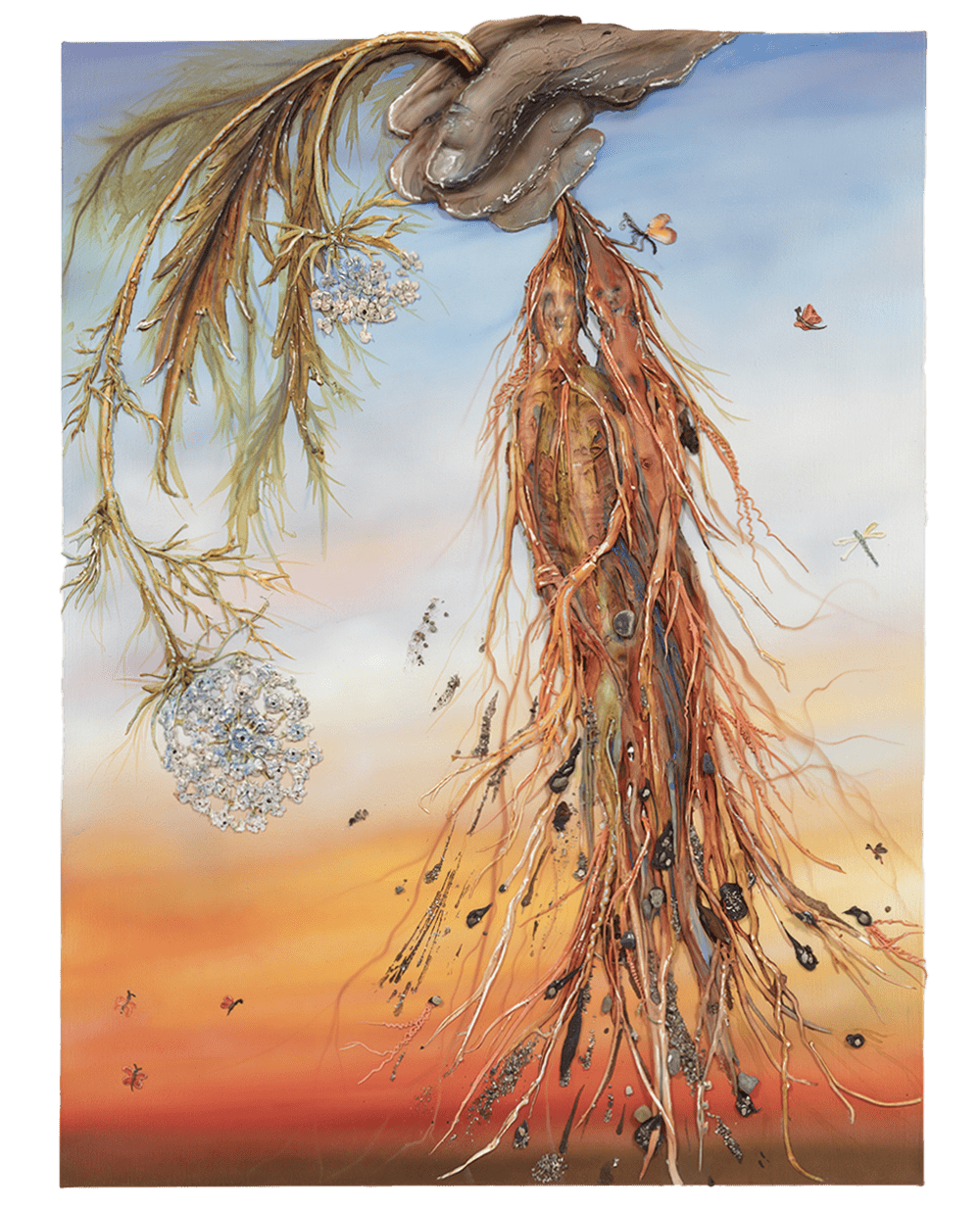

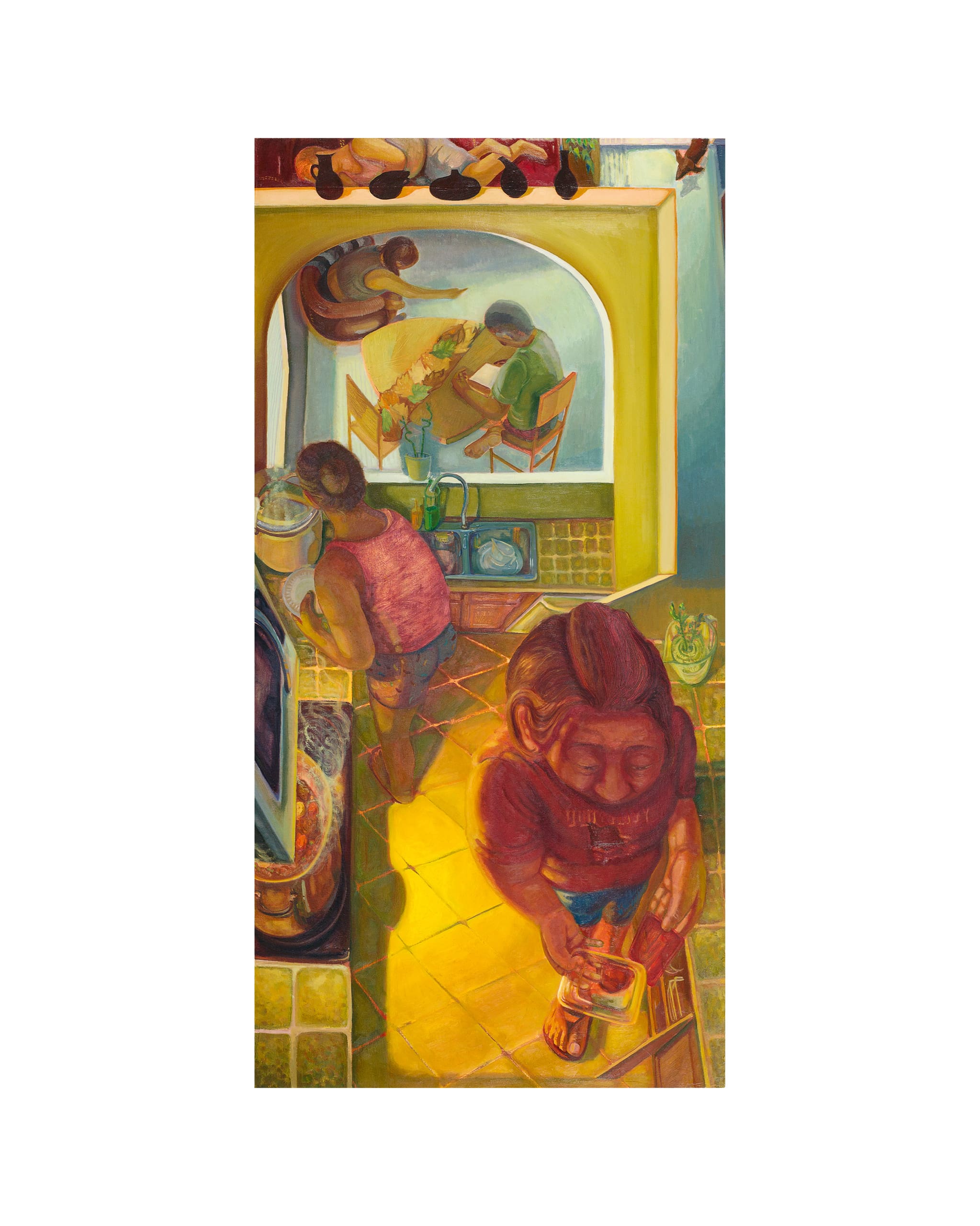

“This is MJ Torrecampo, who is a Filipino-American artist that we exhibited at the fair last year,” she says, gesturing towards a painting of warm domesticity. “She makes art about growing up in a multifamily Filipino household in Florida—she actually grew up in a very similar home as me. And I love this painting because it’s just so cool to see your own story reflected back in art.”

It’s five weeks out from this year’s Future Fair but Mijares Fick says she doesn’t feel too stressed. “I feel incredibly calm,” she says.

Part of that is because of her practice of meditation. For several years now, Mijares Fick has started each morning by setting an intention to start the day. “It’s a ritual that just deeply grounds me and calms me,” she says. “And when you’re organizing a big event, there’s just so many moving parts—a lot of parts of it you don’t have control over.”

She meditates in her home office, where she keeps an altar with objects and effects dear to her. Beside a print of a painting of the Virgin Mary by the Filipino jewelry artist Communion by Joy (“coincidentally, she also made the rings that my husband bought me”), holding pride of place in the altar, is a photo of her lola. “She passed away around this time last year,” Mijares Fick shares.

That photo of her grandmother rests on a wooden boat, on top of a rosary made of beads from the Philippines. Other elements of Mijares Fick’s altar include shells, crystals, candles and orchids but the most curious element might be what seems like an early 1900s photograph of an Igorot woman that she says she found on eBay.

“This one really struck me,” she explains. “I think about how she’s being photographed by a European person. And I think about how she’s being objectified or looked at as a specimen. I think about her face in this photo and what she’s carrying. And I think about how her story may be lost beyond this photograph. And I think about her every day.”

Every morning, Mijares Fick sits at this altar and meditates for 10 to 15 minutes, thinking about her purpose. “What I’m trying to tie together here is this idea of creating a space to exhibit artists from all over the world and from different cultures,” she says. “It’s really important for me that we can share their stories and elevate them because now we’re at the position, in our day and age, where we can be the gatekeepers as to say who gets to have their stories told and how their stories are told.”