Photographed by Camille Robiou Du Pont

One Saturday afternoon in Siargao, designer and visual artist Carlo Tanseco tells Vogue about how the island opened his mind and shaped his craft.

There’s this joke that Carlo Tanseco likes to tell. When he was in college, he enrolled in the University of the Philippines wanting to take up archaeology, but accidentally ticked the box beside “architecture” because they share a prefix.

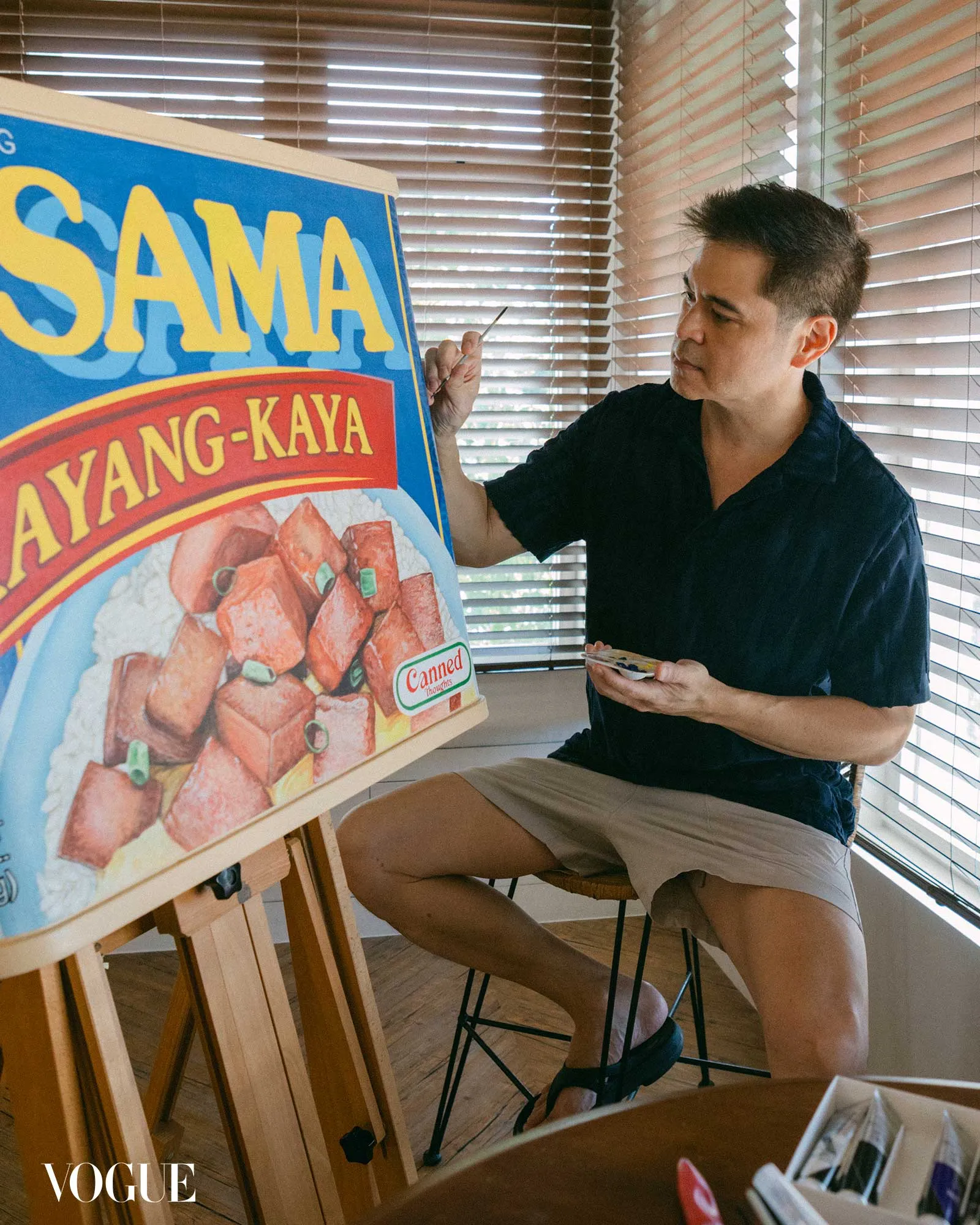

The designer and visual artist is all smiles as he shares this with Vogue one early Saturday afternoon. We are in Neverland Siargao, the eatery he and his partner own in Barangay Catangnan, General Luna, whose comfort food menu and in-house granola takeaways attract an array of patrons. Prints of Carlo’s paintings are hung on the walls, lending an even cheekier touch to the already eclectic space. Garbed in a loose button down, shorts, and slippers, Carlo is perfectly at home.

“I’m a citizen of both Manila and Siargao. But in my heart, I’d rather totally be in Siargao,” he says. When we speak, he’s currently in what he calls “production mode,” creating pieces for his exhibit The Anthropometric Man at Art Cube Gallery, on view until November 1. His days typically begin at 7:30 in the morning, and sometimes he goes straight to his studio. His canvases only get their strokes when the sun is out, because he only paints in natural light; the colors painted in the evening, he says, will look different the morning after.

“And surprisingly, I forget to eat lunch,” he teases. “I turn on my podcast, music, or whatever… more podcast, I like people chattering.” When he remembers to eat, he usually has a quick meal mid-afternoon so he can chase the light and make more progress before sundown. “My studio has a view of the sea. Ironically, I cannot frolic in the sea,” he laughs.

Most of his conceptualization work is done on the island, and he surmises that the relaxed environment lends to the ease of creative thought. He keeps a notebook with him at all times, ready to jot down an idea or a feeling the moment it sparks. Handwritten words and sketches fill his pages, and when he flips through them, he rediscovers concepts he can expand.

One of these was the seed of his Jose Rizal matchboxes series. On one motorcycle ride through Siargao, he was preparing to cross the Catangnan Bridge before realizing it was under construction, and makeshift wooden planks were to serve its purpose in the meantime. In that short pause, he noticed a matchbox at the foot of the bridge, which catalyzed the project.

For The Anthropometric Man, he revisits his undergraduate years, specifically a textbook he had that opens up to a figure of a man labeled with measurements. It’s intended to guide architects in their practice to ensure that their designs are functional and comfortable for different individuals of varying sizes.

Excitedly showing us a preview, he swipes through his phone to reveal a play of dualities within man and the universe: yin and yang, sunrises and moonsets, fire and water. The individual acrylic parts are held together by stainless steel screws to “give the impression that this is the joint, and it can only go so far.” His works reveal the possibilities and limitations of our innate dichotomies, all while integrating technical architectural elements that speak to his own identity.

When he was younger, Carlos didn’t want to become a full-fledged visual artist despite enjoying the craft. He recalls, for example, painting fruits in art classes with Rody Herrera in Greenhills at 7 years old. Though he has no formal training in art, he learned by way of certain subjects required for his architecture degree like one focused on rendering, which he describes as “sort of painting.”

He eventually became a furniture and product designer and worked with DTI-CITEM for several years. He cites these stints as being foundational in sharpening the basic principles of planning with the end user’s needs in mind. His architecture background is what informs his process to this day: he begins with a grid, pattern, or some semblance of order, before messing it up. “The grid emphasizes the lack of order and the lack of order emphasizes the need for the grid, which is order,” he expounds. “Because of architecture, my style has been very regimented, patterned, regular, symmetric. In fact, you can see it in the DNA of my work, the influence of architecture is written in.”

This meticulous disarray is evident in his latest project, but also in his exhibition Sari-Sari Sabi-Sabi for Art Fair 2025. Filipino snacks typically found in a sari-sari or neighborhood convenience store are reimagined with ingenious positive affirmations and word plays. A Cloud 9 chocolate bar, for instance, is emblazoned with the statement “If you could dream it you can achieve it.”

It was an expansion of his show Canned Thoughts, where he similarly revamped canned goods. “The can for me is order in the sense that these are measured, these are what people have known to be as a meal.” He further explains that in a sari-sari store, these viands are stacked to form a grid. “I start with not only a grid, but even patterns,” he adds, pointing out that what might register as negative space in his work is actually inundated with geometric shapes. Even for The Anthropometric Man, each panel is given life by crashing waves or turning gears, among other things.

That he is able to freely explore creative visual pursuits at this stage in his life is a blessing. “The thing about doing it at this time is I have so much material from my past. I have a lot of things to say,” he shrugs. “It’s a risk all the time.” Before he solidified Anthropometric, he intended to do a show centered around Siargao before realizing that it is a phase in his life that he wants to live out more. Now shuffling between the city and the coast, he considers his time down South as invaluable.

“What I love most about Siargao, it’s a community first and foremost. We are just really guests,” he narrates. “I like that your waiter or server in a restaurant is your gym-mate the next day. The best surf instructors sometimes can be your bartender.”

The subject of his gushing eventually lands on one of his favorite purchases since settling down on the island: a tuktuk. He and his partner invested in one for the restaurant, and Carlo loves how he can load things into it for transport and how when it rains, there’s a roof over his head.

Once, while out for a ride, he caught himself beaming.

“Why am I smiling?” he wondered aloud.

But really, the privilege of rediscovering himself in a foreign place is just one in a slew of simple joys the island brought about. When he first travelled there over the pandemic, he felt its impact heal him; this small slice of land and water in Mindanao triggered a shift in his heart, mind, and body. In Siargao, Carlo’s life looks like crossing wooden planks on a motorbike or getting caught in the rain without a roof. It looks like sitting in front of a canvas until the sun sinks into the sea outside his window, looking on at what has been and what could still be.

By TICIA ALMAZAN. Photographs by CAMILLE ROBIOU DU PONT. Producer: Bianca Zaragoza.