Audrey Hepburn, New York, January 20, 1967.

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Audrey Hepburn, New York, January 20, 1967.

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Born in New York City 100 years ago today, Richard Avedon was a singular force in fashion and art photography, pioneering a visual style that privileged both formal innovation and a sense of theater—whether he was working in the studio or out on the street. “Avedon’s unflinchingly frank aesthetic has become so much a part of the conventions of photographic portraiture it is easy to forget that he invented it,” Larry Gagosian writes in the splendid exhibition catalog for “Avedon 100,” the sprawling centennial celebration now on view at his 21st Street gallery. “He is one of the greatest portraitists in history, as important to his time as Holbein and Gainsborough were to theirs.”

During his long career, which stretched from the mid-1940s until his death in 2004, Avedon would create some of the defining fashion images of the 20th century for Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, as well as important portraits of civil rights activists, politicians, and outsiders of all kinds. (Together with James Baldwin, a friend of his from high school, Avedon released the book Nothing Personal in 1964, exploring “the contradictions at the heart of American experience.” Included in its pages were his images of figures like Marilyn Monroe, Allen Ginsberg, Malcolm X, and members of the American Nazi Party.)

For “Avedon 100,” Gagosian invited friends, family, collaborators, and admirers of Avedon to select their favorite images from his vast oeuvre and explain what they meant to him. Below, we gather 11 photos from the show, with tributes from Vogue editors and contributors.

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Kara Young, model:

Richard Avedon’s image of Nastassja Kinski and the serpent moved me so intensely. It’s the reason I wanted to become a model. Her gaze is so serene, so fearless and inviting (no danger here). That someone could be so woven into something so forbidden—I wanted to be both her and the snake. Years later when I worked with Dick, my dreams came true. I know how he brought out that look in Nastassja’s eyes. He taught me to do the same—to always have a thought, a memory, a feeling, some knowledge to bring out a radiance. What was hers?

Brooke Shields, model and actor:

I remember taking this photo and the feeling of excitement about how architectural Richard Avedon’s eye was. It was never just about the clothes, much to the chagrin of fashion editor Polly Mellen. It was about posture, an eyebrow raised, a specific attitude that was inspired by every look and created especially for every image. I loved the cinematic freedom that was borne each time those large metal doors in his studio were shut and it was just me, Dick, his assistant, and my favorite songs blasting from the speakers. I was nine years old when I first worked with Dick, but it wasn’t until my early teens that I started regularly coming to his studio after class, which was the most incredible after-school program there ever was. Shooting with Avedon felt like shooting mini movies with every outfit. It was always a nonjudgmental exchange of creativity and an exploration of the unexpected. He was the ultimate maestro.

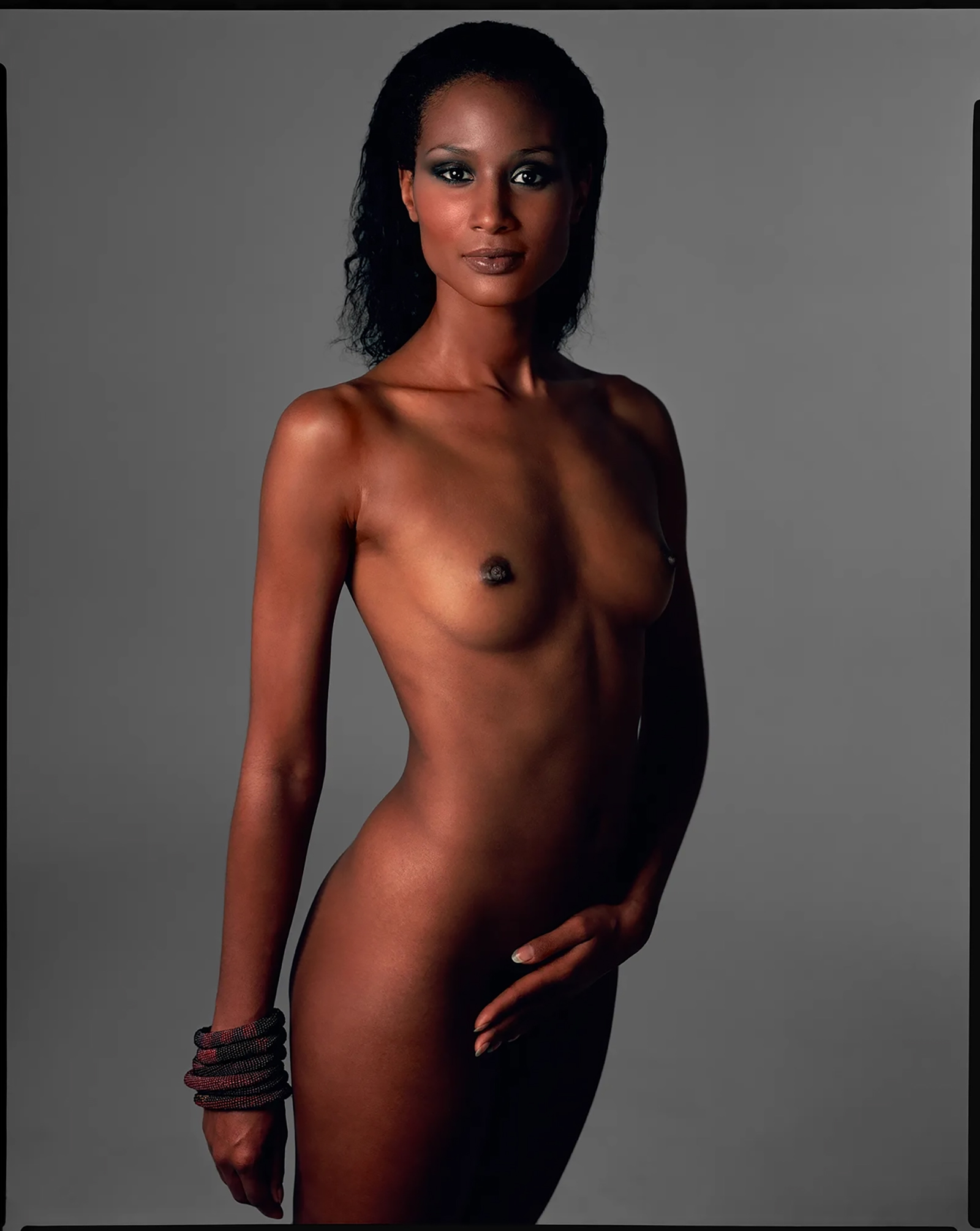

Beverly Johnson, model:

The nude photo Dick did of me for Vogue magazine… It’s one of my favorite photos. One of the greatest fashion photographers of all time… I recall walking into his austere studio and the tone of heightened professionalism that was set. You knew you were in rarefied air. The studio was set up so that he could photograph me for Vogue. He captured some of my most cherished photos.

Pat Cleveland, model:

I remember the day this image was taken as wonderful. I was always so happy to work with Avedon because he allowed me to move and not be rigid or still. Ever. At the time, there weren’t cameras with rapid-speed shutters that could easily catch an action shot. But Avedon was quick. He was agile, like a gazelle, and so was his assistant, who leaped along with him while holding on to an umbrella that reflected the light. It was actually a funny sight to behold. I was in front of the camera, no seam, the cement floor curved into the wall, and it was all painted white, and Avedon would say, “Pat, jump!” I tried not to look like a frog, so I sort of leaped, keeping my eye on him for the next instructions, trying to keep up. Eventually we were flying. He was quick, I was quick, it was like two gazelles running back and forth, trying to catch the perfect image. Avedon also let me come with him into the darkroom when he’d develop the photos. That was magic! I’d be there, in the dark, watching the images come up in the chemical trays. He would become happy when he looked through the contact sheets; it was like a treasure hunt for both of us. He would say, “How do you like that, Pat?” And I would say, “I like it, Avedon.”

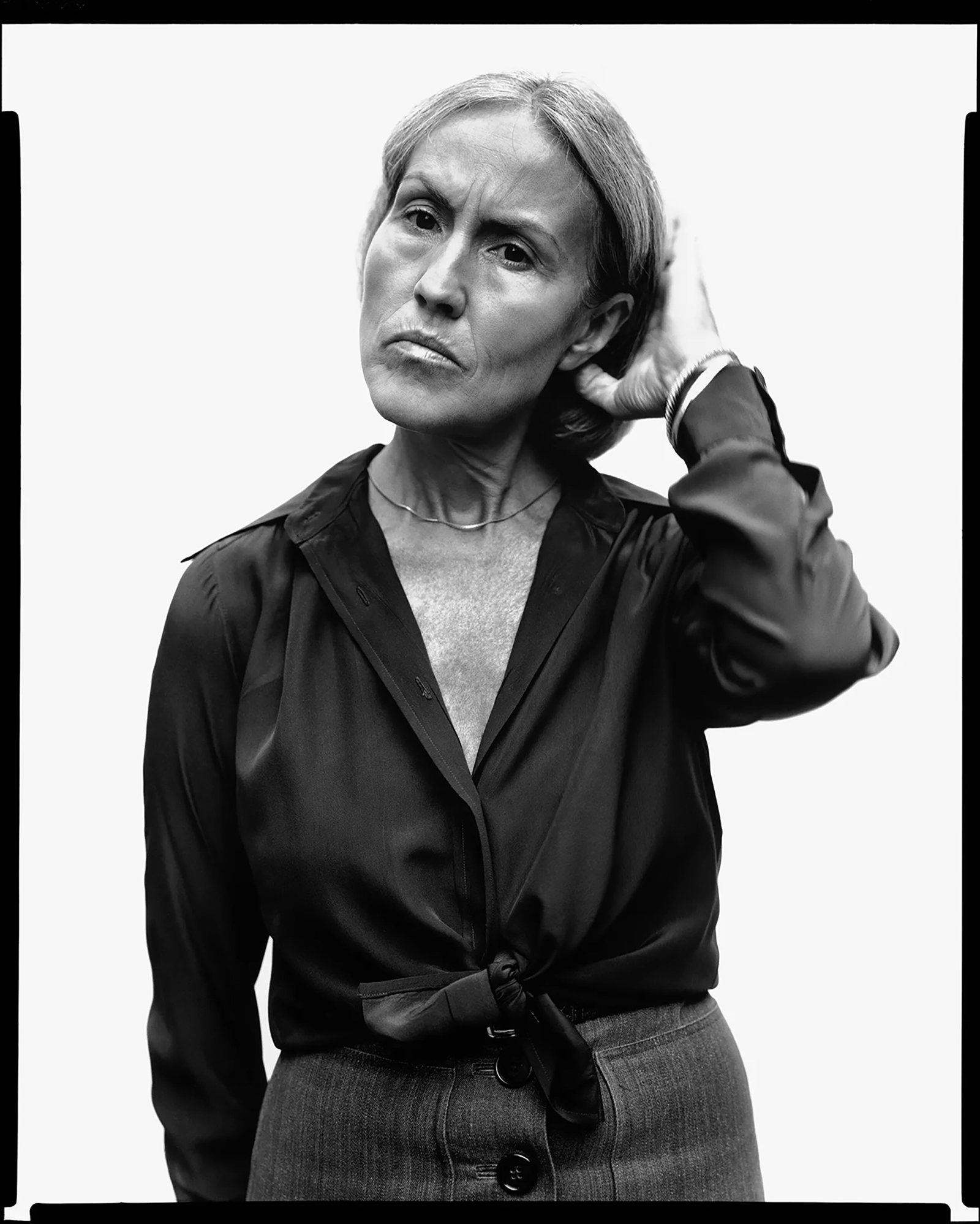

Ivan Shaw, corporate photography director, Condé Nast:

Avedon, in a sense, turned his camera around when he took this portrait of his close friend and collaborator, the legendary Vogue fashion editor Polly Mellen. It was Polly who stood by his side when he snapped the now iconic images of Twiggy, Penelope Tree, and so many others—pictures that elevated Vogue above everything else on the newsstand. Although I spent 22 years at Vogue, sadly I missed working with Polly by five years. But I know so well the intelligence, creativity, and courage you see in her eyes. It’s what Avedon saw too and what he captured so brilliantly. It’s what is within every great Vogue fashion editor.

Lauren Hutton, model and actor:

I worked with Dick often, and I’m always drawn to this image. This was my standard uniform: my hair twisted up under a WWII GI hat so it fell out coiffed, white shirt, blue-jean miniskirt, and my only pair of shoes, white Sperrys. I always said that when it got too cold to wear my Sperrys, it was time to leave New York for an adventure in a warmer climate. I remember the day this image was shot: Dick was doing something near the front door and looked up when I breezed in. He leapt into action: “Follow me! Right now!” And I said, “Yessir,” dropped my bag, and scooted after him. Dick moved like a dancer, so I remember him run-dancing straight for the huge, perpetually ready, dark studio in the back. He went right by the dressing-room militia, where its general, Polly Mellen, his fashion editor, was yelling, “No, Dick! No.” She wanted to dress me in the clothes she’d brought, but we zoomed right by her. We got to the camera, and he told me, “Just stand in your light.” I stood there and looked straight at him next to his beloved Rolleiflex. He took three fast snaps and pronounced, “Lauren! That was fantastic!” It all happened so quickly I didn’t know what we got, but the process made me fall in love with Dick all over again. A few months later, Vogue came out, and there I was, straight off the sidewalk.

Veruschka, model:

When I arrived at the studio that day, they had also invited Yogi Swami Satchidananda to supervise and suggest some yoga positions, but before he could suggest any pose, I kind of snuggled into one. I was not a yoga expert, but flexibility came naturally to me, probably due to my long limbs. Dick loved that pose, and everybody else, as usual, agreed. To be in that yoga position long enough to get the picture right was sort of uncomfortable, especially since Dick and I were busy observing and trying to figure out if the matching socks of Yogi Swami Satchidananda were a choice for the occasion (a Vogue shoot) or a coincidence and watching Ara Gallant, the talented hairdresser, combing with creative strokes his long hair and beard. There was always a feeling of collaboration when working with Dick. One felt always encouraged to be different, to try new things, to be confident; working with him and his team was always special, as he had a gift for making you feel unique and loved, giving you his total attention. That’s a special gift.

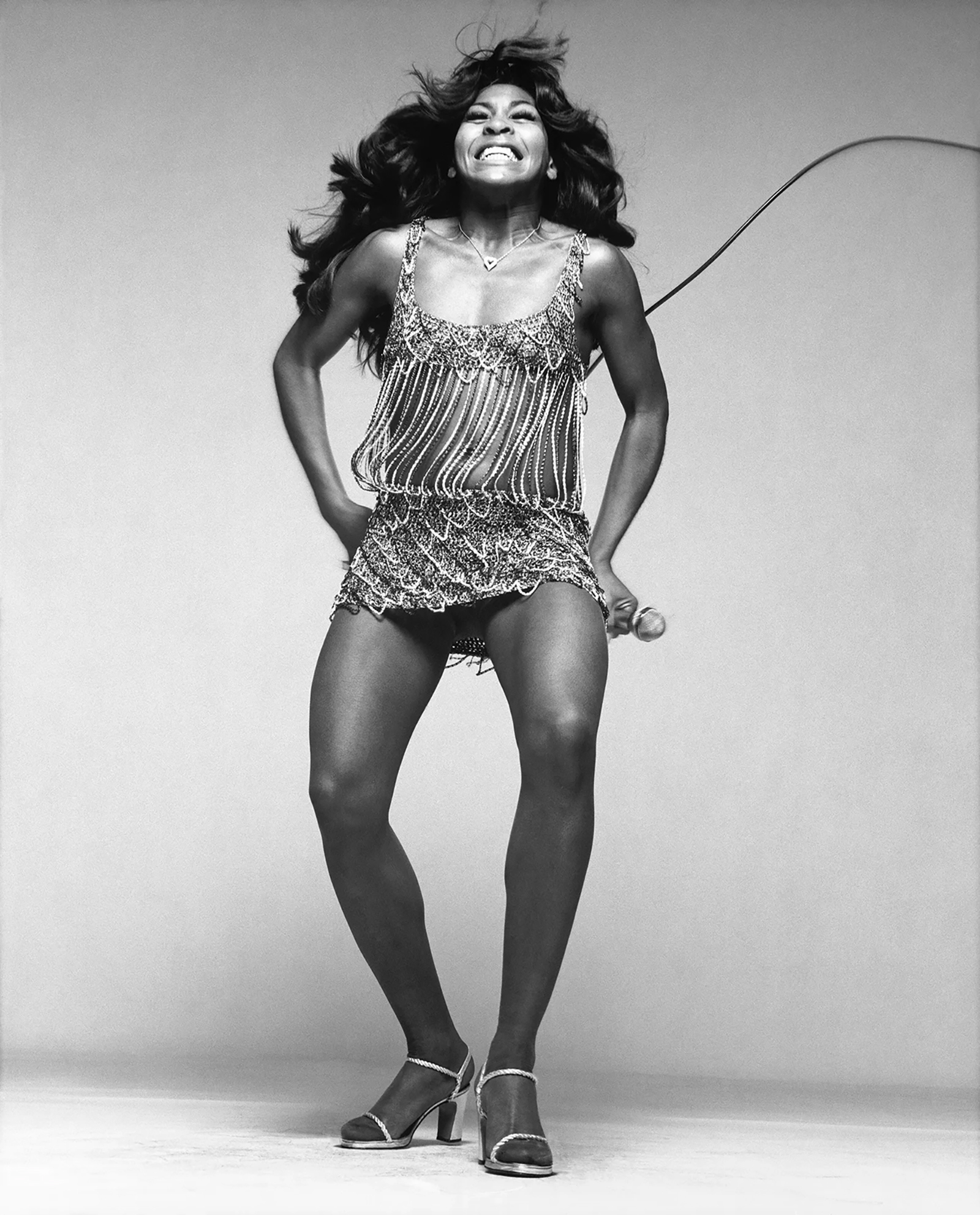

Tonne Goodman, sustainability editor, Vogue:

In 1971, Ike and Tina Turner performed at Carnegie Hall and it was recorded live. I was there. I invited my mother to join me, and we had a wonderful, exuberant, and thrilling time. This photograph of Tina Turner captures the visual truth that every one of Richard Avedon’s photographs does, with no exceptions. He saw right through to the truth of anyone and everyone. Tina’s ferocity tells her truth.

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Dara, fashion director, Interview magazine:

For me, the best fashion photography goes beyond the limit of reality to capture the essence of a subject, style, or mood. Avedon takes the icon Audrey Hepburn and replicates her image in a way that, while deifying her, exerts the artist’s power to manifest his vision and manipulate ours. Many denigrate photoshopping as an evil intervention of our time, but the process has always existed, even before the program. I love Avedon’s blatant disregard in the darkroom because it pulls back the curtain on why many of his photos succeed in seeming beyond our grasp—it’s because they are. What’s in front of the camera is only as important as what’s in someone’s mind. That is true even outside of photography, so why not?

Hamish Bowles, editor in chief, World of Interiors, and global editor at large, Vogue:

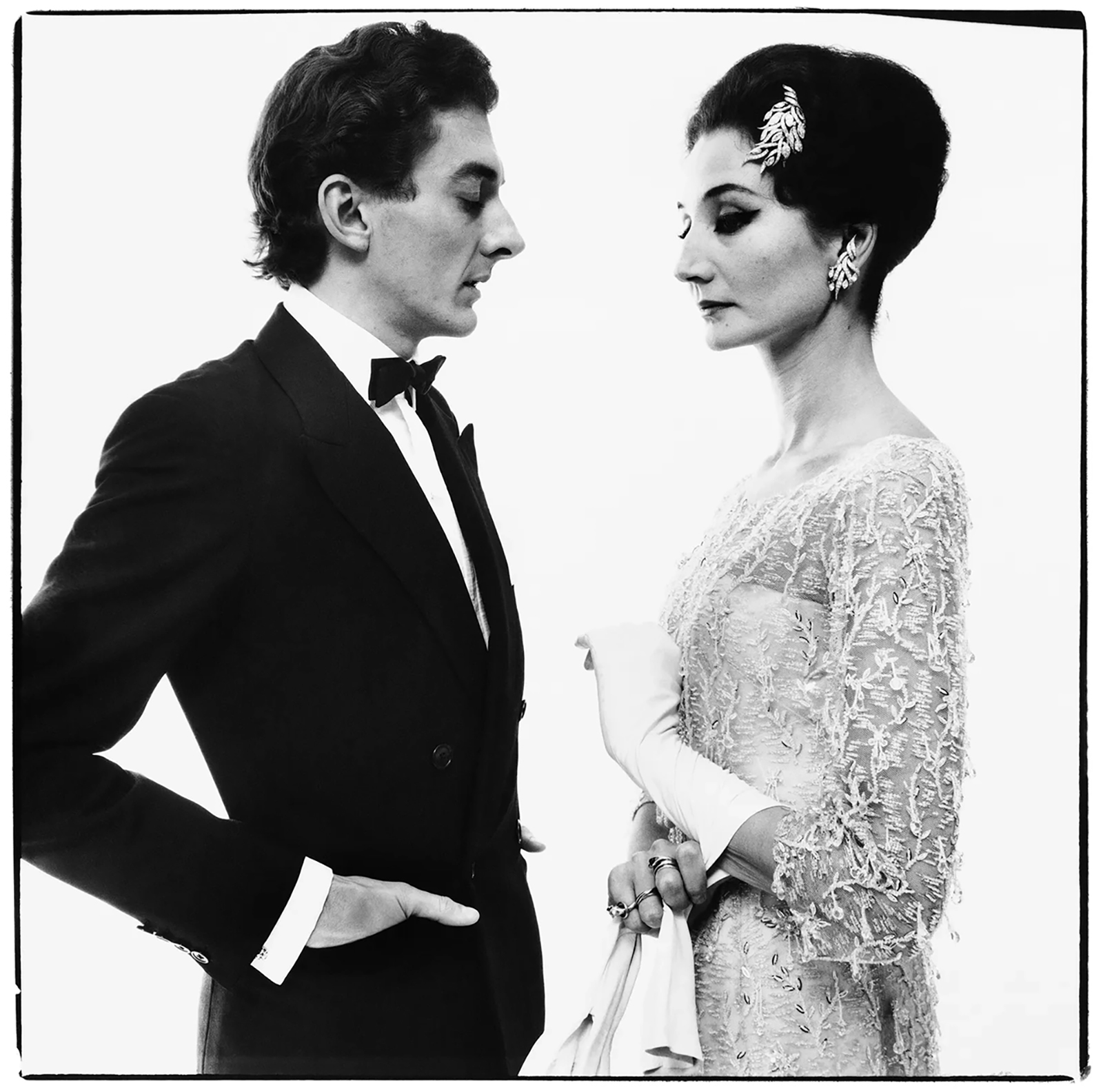

With her proud raptor’s profile and fluttering, feathered voice, the Vicomtesse Jacqueline de Ribes stood out from the couture crowd like a bird of paradise in a cage of canaries and parakeets.

“The Vicomtesse de Ribes is a rare person,” wrote Yves Saint Laurent in an open letter handed out when she debuted her first fashion collection, 20 years after she sat for this Avedon image. “She is a beacon, she radiates, her long neck gleaming with the brilliance of a thousand lights. Lyre-bird. King bird.… She is the pearl in the King of Poland’s ear, the Queen of Sheba’s tallow-drop emerald, Diane de Poitiers’ crescent tiara, the Ring of the Nibelungen. She is a castle in Bavaria, a tall, black swan, a royal blue orchid, an ivory unicorn. Her eyes are the reflection of the moon on the waters of Baden-Baden. She is the quivering aigrette topping a maharajah’s turban in a whimsical and baroque spiral.”

De Ribes shared not only a Madame Gautreau profile with [Chilean diplomat Raymundo] de Larraín but also an interest in dance.

He was a protégé of the balletomane Marquis de Cuevas, who used the considerable fortune of his wife, the heiress Margaret Strong (a beloved granddaughter of John D. Rockefeller), to support the Ballets Russes, which was later renamed the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas.

De Larraín was fabled for his exquisite designs for the company’s production of The Sleeping Beauty, in which the role of the prince was danced by Rudolf Nureyev in 1961, making his first appearance after his defection from the Soviet Union. De Larraín would subsequently marry his mentor’s 80-year-old widow, who was 40 years older than her groom. De Larraín gave her a wheelchair and new teeth for their wedding.

Avedon’s sitting was intended to symbolize narcissism, and his casting was faultless.

Tyler Mitchell, photographer:

I look at this photograph of Richard Avedon and James Baldwin and see the many intimacies of a deeply collaborative friendship between two artists. Oftentimes we are presented with images of Avedon and Baldwin in staged scenarios that position them as titans. And while they are titans, I love how purely unguarded this moment is. It’s a moment of closeness and reflection. It reminds me of the capacity to remain human throughout the process of making, growing, creating, and evolving.

Quotes excerpted from Gagosian’s “Avedon 100” catalog, available for purchase here.

This article was originally published on Vogue.com