PLACE AT THE TABLE

Arnault, wearing Dior, at Dior’s under- renovation flagship in Manhattan. “It made you dream,” she says of visiting Dior at 30 Montaigne in Paris with her father as a girl. Fashion Editor: Tonne Goodman.

Photographed by Annie Leibovitz

At the end of her first year as Dior CEO, Delphine Arnault is proving to be a powerful protector of legacy—and a leader poised to make waves.

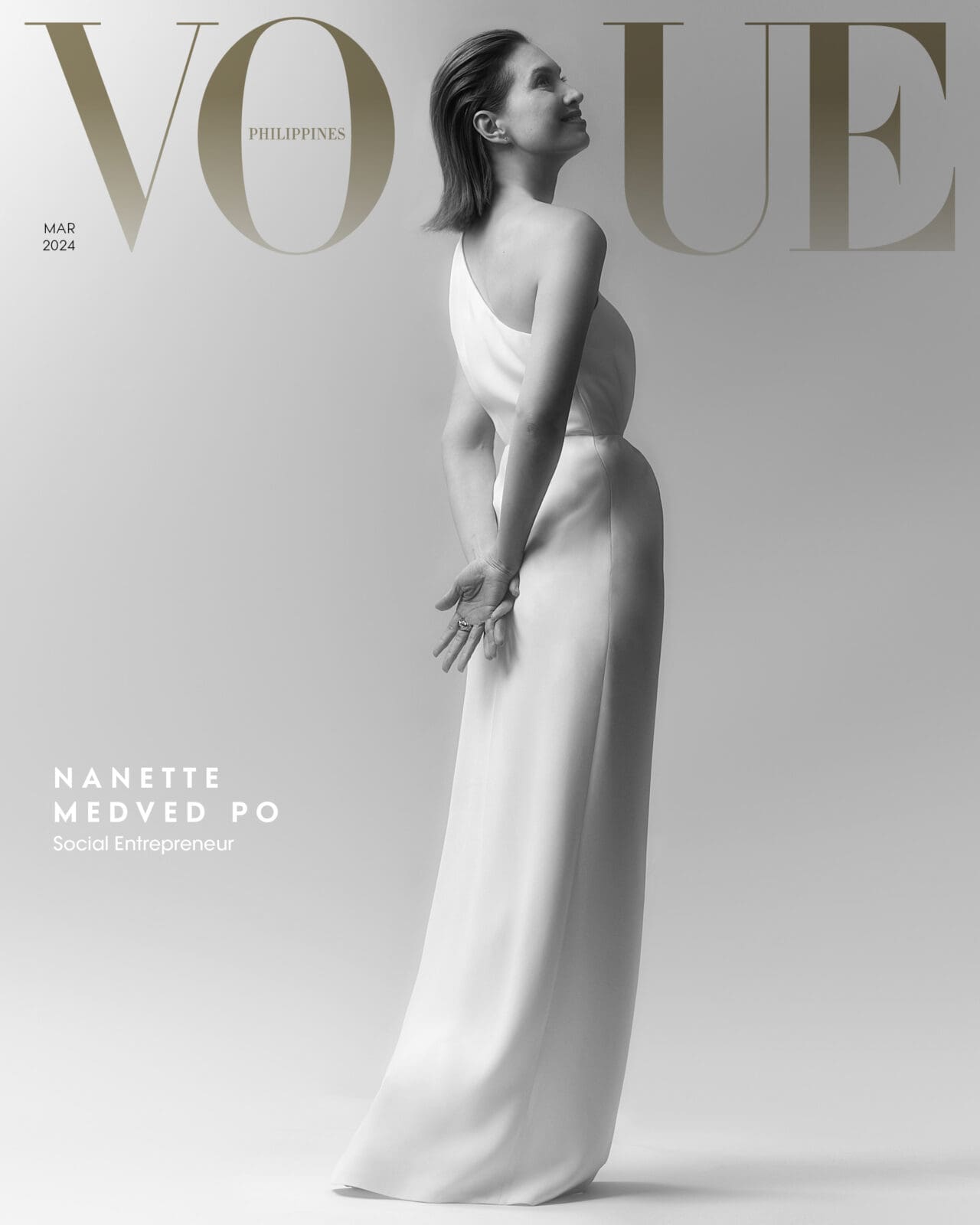

Delphine Arnault appears in Vogue Philippines’ March 2024 issue, themed “Raising Hope” in the spirit of International Women’s Month. Visit vogue.ph everyday this month for daily features on inspiring women, as nominated by the people whose lives they’ve changed.

On the morning of February 1 last year, imperturbably recovered from a party to mark her departure from Louis Vuitton, Delphine Arnault stepped into her new office in Paris as chairman and CEO of Christian Dior. The eldest child and only daughter of Bernard Arnault—who is, more often than not, the richest man in the world—she had moved up through the ranks of her father’s companies at LVMH over the course of a couple of decades, quietly absorbing every aspect of the fashion business. Now here she was, at 47, with the crown jewel in her hands: the first fashion house her father had ever bought, the place where he had taken her at weekends as a child, the home of the much-loved Monsieur Dior (as its employees still call him), who, 77 years ago, changed the way women dreamed about their lives. Christian Dior is a name inextricably linked to the history of France—and on that day Delphine Arnault became the first woman ever to be in charge.

Not long afterward she called her friend Larry Gagosian in New York. “Larry,” she said, “I’ve got this big office. But it’s lonely up here!”

Being a member of the Arnault family, while companionable in many respects, carries its own form of isolation. Close-knit and very private, the Arnaults have been subject to increased public attention since their patriarch parceled out decision-making responsibilities over the future of LVMH to his five children (via a holding company where they each have a 20 percent stake). “When you grow up in a well-known family, you don’t have the right to make any mistakes,” Delphine’s brother Antoine explains. “People look out for the slightest flaw.” months into her reign at Dior, in the lobby of creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri’s studio in Paris. Discreet in demeanor, fragile featured, with a composure to match her impressive nearly six- foot height, Delphine greets me in a navy Dior trouser suit, her hands in its pockets. It’s the eve of the spring- summer 2024 show, and in the studio three black leather seats have been arranged in front of a sample of the neon pink and yellow set. Models are walking back and forth, small adjustments made, accessories considered. Tiny turrets of strawberries and raspberries are laid out before us. Maria Grazia, clad in jeans and a black sweater, sits next to Delphine and introduces a little gray poodle, whose color, they both note with a smile, is perfectly on brand. “It’s gris Dior,” Maria Grazia says.

If, in 1947, Christian Dior was telling a story about women’s lives—the war they’d emerged from, the future they hoped for—then the first two women to lead his company are telling a new one. With Delphine as CEO and Maria Grazia as creative director, the house of Dior is moving into an era in which two busy working mothers are in a position to determine what women wear, how they feel, and how the people who make the clothes feel too. In Maria Grazia’s view, “fashion has to help you to feel that you’re free.” As Marie-Josée Kravis, a family friend who has sat on the board of LVMH for 13 years, observes, “Here you have two really talented women who are living the message daily. I think it’s a great example for women everywhere.”

As the clothes appear, Delphine and Maria Grazia settle into each other’s company with ease. Delphine absorbs, never intervenes. She has seen this collection in progress twice before. “Every time you see it you get to know it a little better,” she tells me. Dior’s 1947 New Look is reflected in black pleated skirts and refracted in asymmetrical white shirt collars. There’s an occasional kinky touch from strappy black gladiator boots with kitten heels and pearl buttons. There’s a cotton dress made of many different kinds of lace, and a blurred, X-ray-like projection of the Eiffel Tower on a black coat.

“How many looks do you have?” Delphine asks.

“Seventy-eight,” Maria Grazia replies. “Because Rachele cut five.” Maria Grazia’s 27-year-old daughter and cultural adviser, Rachele Regini, is behind us, readying the models and overseeing operations. “Isn’t she a bit too skinny for this one?” Maria Grazia wonders out loud, about one of the models. She turns to Delphine: “I’m obsessed. I don’t want to show too-skinny girls. I want healthy girls.” Then, quietly: “It’s an intense week for you, huh, Delphine?”

Indeed it is. Five days earlier, Delphine and her partner, Xavier Niel—with whom she has two young children—had attended a dinner at the Palace of Versailles for the King and Queen of the United Kingdom (Queen Camilla was dressed by Dior; the French first lady, Brigitte Macron, was dressed by Vuitton). Delphine wore an embroidered wool haute couture coat with a floor-length gown in lace and champagne-colored crushed silk. Tomorrow she will be speaking for the first time to 600 delegates invited to a Dior Summit at the Louvre, a few floors beneath the Mona Lisa. The same spring summer runway show will be put on for them, and they’ll be entertained with talks, parties, and dinners over the next couple of days. “It’s great for them,” Delphine says, “and I think it’s important.”

At dusk, Delphine and I walk a couple of blocks under her ample umbrella to the Dior boutique, where the delegates to the following day’s symposium have gathered for welcome drinks. She marvels at Maria Grazia’s calm organization. John Galliano and Raf Simons, she recalls, would be up all night on the eve of a runway show, panicking and remaking things, whereas Maria Grazia is always done on time. (“I think it’s very important not only for me, but also for the people who work with me, to have time for their personal life,” Maria Grazia tells me later. “It’s nice for everybody to have dinner at home.”)

The original site of Christian Dior’s 1947 debut is 30 Avenue Montaigne—or “Trente Montaigne” for short. Extensively remod-eled, it reopened in its new incarnation in March 2022. And that’s not the only sign of a company expanding at speed. There are store directors from all over the world here—“the heart and soul” of the company, as Delphine will tell them. They haven’t been brought together since before COVID, and since then Dior has created more than 6,600 jobs. One million of their iconic Lady Dior bags have been sold.

The delegates are here so they can feel part of something both venerable and new—and keep sales on target. More than 40 languages are spoken among them. Delphine greets as many people as she can, traveling through the US, Mexico, Southern Europe, and Japan in the space of a few minutes. She asks what is and isn’t selling, which celebrities young people look up to in different zones, who are the competing brands? And then, always: How is the Lady Dior bag doing? The price was increased globally in July. Is it too high for their particular market?

Meanwhile, there are rowdy whoops from the selfie taking crowd—a giant Dior school reunion. The Korean delegation has gathered for a photo on the new glass staircase designed by Peter Marino. They invite Delphine to join them, and she gamely takes her place at the center of the group.

Some weeks later, Delphine and I have lunch at Le Stresa, a small, family-run Italian restaurant on a side street near the Avenue Montaigne. It’s a favorite among the fashion and film crowds and is packed with models and moguls during Fashion Week. “I love this place because it’s kind of homey,” Delphine says as she greets one of the brothers on duty. We’ve just spent an hour at the recently rehoused Dior archive, sighing over vintage shoes rescued from flea markets and drawers full of original sketches by Christian Dior and Yves Saint Laurent. Not for the first time, she told her driver that we would walk. With her usual elongated elegance, Delphine is wearing a cropped cream bouclé jacket with CD logo buttons over black wool trousers and a white slogan T-shirt that alludes to Édith Piaf. She orders a caprese salad with a minestrone soup, and a conversation emerges around her finely tuned sense of privacy.

The puzzle of speaking to Delphine Arnault is this: She is palpably friendly but relatively silent. In the course of several conversations with her, I didn’t get the sense that her brief answers to my questions were a mark of hauteur or even reticence; though she may have been wary of being interviewed, she gave me a number of opportunities to observe her world. It was more that she seemed not to have a narrative relationship to her own life: Nothing came out as a story. This is, perhaps, a form of modesty, and the modesty in turn a mark of politeness. One thing that emerged repeatedly in my conversations with others—aside from the Arnaults’ tireless work ethic—was that they have very good manners. “Delphine has a form of reserve that I find extremely touching,” Antoine Arnault tells me. “Some confuse this with arrogance. My sister is very discreet by nature, and the education we received obviously nurtured this discretion.” When she acts, he says, she acts thoughtfully: “At 25 it’s called shyness, at 50 it’s maturity.” With me Delphine was at her liveliest when praising others, whether it was the artists whose work she owns or the shop assistant at Dior who’d been there for decades and had recently broken her foot. Her affection and admiration for her father were equally evident. One person I spoke to described the father-daughter pair as having “deep respect” for one another.

‘He never stops,’ she says of her father. “Seeing that as a child forms quite an impression—the dedication he gives to his work’

I came to think of Delphine as a relative of Henry James’s fictional Maisie: the eldest child of divorced parents who is precociously attuned to what the adults ignore. Sidney Toledano, Delphine’s mentor at Dior, speaks of her resilience (“Don’t think life was easy,” he says mysteriously). A photograph of her with her father, taken when she was 16, portrays them as an echo of each other—Delphine, almost at Arnault’s height, has a sweetness of expression that makes her look closer to 12. “I think we all forget that she was rather young, still an early teenager, when her father really built LVMH,” Kravis observes, “and her father is a very good teacher. She’s grown up with the company.”

“I’ve never rebelled,” she says, smiling at the obvious question. Asked if there is a Harry Windsor in the Arnault family, she says, “I hope not!”—and her friends have certainly never heard her say she wants to do anything else. Like her father, Delphine has an instinct for what will sell. Some, but not all, of this comes from experience. “It’s not a rational thing,” she explains; in fact, the only professional challenge she identifies in the course of our lunchtime conversation is that it can be hard to predict, when hiring people, whether they will have this knack. It’s her father’s gift: “When he sees 15 bags on the table, he immediately goes to the bag that’s going to sell,” she tells me in amused amazement.

Delphine is clearly, by nature, a listener—“all ears, all the time,” as one of her friends put it. This unflashy quality may be her greatest strength, and it marks her as unusual in the very male echelons of LVMH: staunch and sensitive in her support of creative people, the originator of a prize for young designers, a proven spotter of talent. If there is a jeopardy at Dior, it’s that it must never fail to lead the creative field, and in that respect Delphine is poised to steer it without ego. Brutal in business, relentlessly hard-working, and firm as a father, Bernard Arnault is known as “the wolf in cashmere.” In 2022 he persuaded the LVMH board to raise the mandatory retirement age for the chief executive and chairman from 75 to 80. That now gives him another five years to oversee his five children. Unless they get unanimous board approval, they cannot sell their shares in the company for another 30 years, and, after that, they can only pass them on to Arnault’s direct descendants. The image of sibling unity, while by all accounts accurate, is also a response to a potential vulnerability: Arnault has taken over companies previously owned by warring families.

Though he has repeatedly said it’s not automatic that a child of his should succeed him at the helm of LVMH (it is “not an obligation, nor inevitable,” he recently told The New York Times), it’s presumed that one of them will eventually take his place. Who that becomes will depend in part on who actually wants the job: Arnault has likened it, tellingly, to a priesthood. Once a month, the father and foreman gathers his children for a 90-minute working lunch on the top floor of the LVMH headquarters at 22 Avenue Mon-taigne. “He’s involved us from when we were quite young,” Delphine explains. “He talks to us about the group strategy, discusses questions that arise. He’s always wanted to pass on his knowledge. It’s a lot of work to choose the houses one buys carefully.”

Now encompassing more than 70 brands, the LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton group is, as Delphine puts it, “the leading business in Europe.” In fact it’s the largest luxury conglomerate in the world, encompassing not only fashion labels but hotels, vineyards, a world-class art museum, and a huge amount of very profitable Champagne. Dior’s significance within this empire is not merely sentimental: It controls 41.4 percent of LVMH. The luxury company plays a heritage role, and an ambassadorial one too: Arnault pledged 200 million euros to the restoration of Notre Dame cathedral and is sponsoring this year’s Paris Olympics to the tune of 150 million euros. French economists have deemed him to be more powerful than a head of state.

His daughter, in a more quiet way, contributes too—to French schools. “I work a lot with education,” she tells me when I ask about causes she supports. “It’s something I do personally with specific schools that I know, who identify very good talents. Students who are super bright and don’t have money to pay for a scholarship, things like that.” It’s not something she talks about publicly.

The dynasty’s wealth has made them an object of some hostility in certain quarters of a country founded on the principle of “égalité”: Last April protesters stormed LVMH headquarters with smoke bombs during long-running strikes over the national retirement age. Delphine’s response to this is apparent bafflement and hurt, along with protectiveness of the staff. “That, sadly, had nothing to do with LVMH,” she says, shaking her head. “They were railway workers. It was intrusive and violent—for no reason. I found it quite frightening that they could come into the LVMH headquarters—there were staff who were trapped and inhaled a lot of smoke.”

Although the Arnaults’ Shakespearean drama has drawn international attention, under French law the redistributive gesture of their patriarch is almost prosaic. Legally, you have to leave assets to your children and couldn’t disinherit them even if you wanted to. So while the intrigue over who will emerge at the top remains, the primary interest in the Arnaults is not so much familial as national. Who will be the custodians of these slices of French history, and the guardians of its future economy?

Delphine, then 16, with Bernard Arnault backstage at Paris Fashion Week, 1991. Courtesy of BERTRAND RINDOFF PETROFF, GETTY IMAGES

As the CEO of Dior, Delphine is the protector of a myth. Everything about it—the original gray and white color scheme, the oval-backed chairs, the references to the New Look, the fabric printed with a map of the streets around the shop—is designed to inspire the sense that if you buy anything by Dior you will own a piece of history. When Maria Grazia looks back to her arrival at Dior seven years ago, she realizes how wrong she was to think of it as a fashion label like any other. “In Paris, Dior is not a brand. It’s much more, because it’s part of the history of Paris and of the French,” she explains. “For me it was initially very difficult to understand this because I came from Italy, and we don’t have this kind of relationship with fashion.” This was reinforced by the globe-traveling exhibition “Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams” and by the republication of Christian Dior’s autobiography, Dior by Dior (which Delphine recently reread and found to be the template for everything that followed). The expansion of 30 Montaigne now includes the Galerie Dior, where the changing room used by Dior’s original models has been reconstructed to look as though those ’50s women had just stepped out to lunch. Even a star-shaped piece of metal that the very superstitious Monsieur Dior found on a sidewalk has been exhibited behind glass, as if it were a Roman relic.

“Dior is the most famous French name in the world,” Delphine says confidently.

It was a very healthy, calm lifestyle, centered on studies and sport,” Delphine reflects, of her childhood. “We weren’t allowed to go out much. I mean, a little, but it was all about working hard. We’d always seen our father working hard—and my grandfather. He was at the office on Saturday mornings—they worked together. Sometimes I’d go with them.”

Arnault was born into a family construction business in Roubaix, northern France. His parents married the same year Christian Dior unveiled his New Look, and three years later his maternal grandfather handed the reins of the business to his father. Arnault was just 26 when Delphine was born. He was married then to his first wife, Anne Dewavrin, who was also from the north of France. Delphine has early memories of her mother’s wardrobe in Roubaix: “She had a ’70s look with long skirts and boots. A bit Céline,” she says. Delphine and her younger brother Antoine were “raised with very strict principles,” Kravis tells me. Famously, Arnault would help his children with math before dinner. Delphine’s friend Almine Rech—a gallerist who sold Delphine her first painting—adds: “The more advantages you have, the more you have to prove: That’s how you are brought up in France.” Though like all siblings she and Antoine would bicker a lot, as the eldest, Delphine was expected to set an example. “Delph” was a studious child who enjoyed math and economics especially. In fact, she was always so well-behaved that Antoine couldn’t quite believe it when he caught her smoking a cigarette out of her window at 16. She insists that she has no creative streak. “When I play Pictionary,” she says, “no one wants to play with me!” She was also keen on tennis—as an adult she has played with Roger Federer and his wife, but it was paddle tennis…. As Antoine remarks wryly: “Despite her perseverance, I have to admit that she is less gifted than the Williams sisters!” The Arnault children were brought up to be competitive: “Just, you know, trying to do your best,” Delphine says. “That’s what you do—of course being very considerate of others, but always trying to do the best you can do.” “That sounds exhausting,” I suggest. Delphine laughs. “Yeah. It is exhausting!” She remembers fondly the three less-driven years they spent in the US, living in New Rochelle, New York, while her father attempted to set up a US branch of the family real estate business. “It was a Franco-American school, so half the classes were in French and half in English. I think American school is less pressurized, so it was fun.” The family returned to France when Delphine was 10, by which time she was fully bilingual.

It was around then that her father made his first acquisition: a company that included the house of Dior. “He’s always had a particular affection for it,” Delphine says. “He had this vision very early on: to make Dior the most desirable brand in the world—along with Vuitton!” she adds quickly. At the time, the company that owned Dior was in bankruptcy. There were, Delphine says, “five Dior shops.” Now there are 245. Arnault took Delphine to 30 Montaigne straight away. “I was pretty awestruck,” she recalls. “It was fascinating for a small girl to arrive at Dior—to see all those dresses, the bags, the hats…. It made you dream.” I suggest that must have given her quite a bit to talk about with her school friends. Immediately, the family modesty takes over, as if shutting a door. “We didn’t speak about that,” she says quickly.

That first visit to Dior was the beginning of a long-standing habit: Arnault went on to take his children into stores every Saturday, paving the way for the sorts of trips he makes with Delphine now. “When I go to Asia with him, as I have several times this year,” she says, “we spend a week visiting a huge number of shops.” These tours are like celebrity appearances—Arnault is often delightedly mobbed in China. On their most recent visit, she reports, laughing a little, “we visited 250 shops in five cities, walked an average of 15,000 steps per day, were on our feet for 16 hours a day, in 95-degree heat. He never stops. Seeing that as a child forms quite an impression—the dedication he gives to his work.”

When she was 15, her parents divorced, and Arnault married the Canadian concert pianist Hélène Mercier. (Arnault also plays classical piano, and the children were brought up to do that too, though Delphine claims, once again, to have no creative talent.) Arnault and Mercier went on to have three sons together—Alexandre, Frédéric, and Jean. The latter two were taught literature by the future first lady Brigitte Macron, who remains a good friend of Delphine’s. Dewavrin—“Mamoune” to her grandchildren—has since married Patrice De Maistre, the former wealth manager of Liliane Betten-court. Antoine observes that Delphine is like their mother “in her altruistic and pleasure-seeking character. Both of them cultivate the French ‘art de vivre’ and a remarkable sense of family.” At 17, Delphine sold perfume at Dior, before going to the London School of Economics and to business school in Lille. She was given her first Louis Vuitton bag at 18—a Noé. Though she worked at McKinsey for a couple of years after graduating, she was always bound for the family firm. As Toledano puts it, she “has Dior in her blood.”

Delphine Arnault’s sense of humor tends toward irony. “Her humor has a nice bite to it,” Gagosian comments, “but she’s never mean.” Long-term collaborators have benefited from the scale of her vision, the nuance in her approach and the mischief in her smile. She’s passionate about contemporary artists—their lives as much as their work—and has brought them into the fold with great commitment. She has a fearless relationship to risk, but is more moderate and ana-lytical in her thinking than many in the fashion world, who rely on impulse or intuition. Beneath her sleek exterior, she is a woman who gets to work and gets the joke. Rech reminds me that the Arnaults are from the north of France. As a result, she says, the family sense of humor is basically British.

Delphine with her younger brother

Antoine Arnault in Paris, 2011. Courtesy of BERTRAND RINDOFF PETROFF, GETTY IMAGES

Delphine’s first job within LVMH after graduating was with John Galliano in 2000. She was 25. Galliano was at Dior but also working on his JG label out of an old doll factory in the 11th arrondissement—that’s where Delphine began. At the time, they were reviewing the brand’s graphic identity, and Delphine helped Galliano find graphic designers, manufacturers, and suppliers. Very quickly, Galliano remembers, she could see what he was looking for: “a sense of irony. Sometimes that doesn’t work in France.

And honestly, she just got the right people together.” When Galliano’s Jack Russell terrier had a litter, Delphine took one of the puppies.

Delphine married Alessandro Vallarino Gancia, the heir to an Italian wine fortune, in 2005, and Galliano designed her a fairytale wedding dress that took some 1,300 hours to make. “That was fun,” he remembers. “The fittings were bonkers—all the in-laws were there, the real mother, hundreds of guests including politicians, business leaders, actors, and fashion stars; “the Mount Olympus of VIPs,” according to Le Monde—took place at the Château d’Yquem, owned by Delphine’s father. It was on the cover and took over 22 pages of Paris Match. The marriage lasted five years.

Delphine wasn’t in charge of Dior in 2011 when Galliano was dismissed after making antisemitic remarks to strangers, but, as she recalls, “I was in the room when my father’s assistant came in and said, ‘John’s been arrested by the police.’ It was a shock. The things he expressed, the words he said: They weren’t acceptable,” she says, more in sadness than anger. “It was a very tough moment for the house. But it’s in moments like those that one learns a huge amount.”

A year earlier, Delphine had started seeing her current partner, Xavier Niel. Sometimes referred to as “the French Steve Jobs,” Niel is a tech billionaire who founded the telecom company behind the French internet service provider Free, and who is also co-owner of Le Monde. If Delphine is influenced by her father, her outlook on life is now shared with Niel, a businessman who did not grow up wealthy and who is something of a hero in France thanks to his large-scale gestures in support of new talent. His business incubator, Station F, is known as the world’s largest startup facility, and 42 is a pioneering free computer science school.

Niel, who dropped out of school at 19, made his first million by the age of 24 in a colorfully French way: by inventing a sex chat service for the Minitel, France’s pre-cursor to the internet. Evan Spiegel, the cofounder and CEO of Snap, describes him as “an unbelievable friend and mentor to me.” In his early 20s Spiegel would stay in the Arnault-Niels’ pool house when he came to Paris, and when he went out walking with Niel people would come up to Niel in the street “to thank him for what he’d done for France.” Now Spiegel and his wife, Miranda Kerr—who were introduced to each other by the couple—have bought a house next door.

Delphine and Xavier’s daughter, Elisa, is 11, and their son, Joseph, is 7. (Niel also has two older sons from a previous relationship.) Becoming a mother puts things into perspective, Delphine suggests: “Everything becomes relative.” “She’s an incredibly concerned mother,” Rech had told me of Delphine. “I remember how happy she was when she was pregnant, with her boy. She had a few weeks where she could not go to her office and she could go to school, whenever it was the moment, to pick up Elisa.” A few years before Galliano’s departure, Delphine had befriended another designer. “We had many secret meetings,” Nicolas Ghesquière recalls. “It’s quite funny to think about it now—Paris is very big but also very small.” He was at Balenciaga, she was deputy managing director at Dior, but she also played an important role in the search for talent in the wider group. They spoke about a job, but Ghesquière wasn’t ready to move. Even years later, when he was offered the post as creative director of womenswear at Vuitton, he said no initially—until he discovered that Delphine would be moving there too. “And that was the deciding factor for me.” She has, he says, changed his life.

In the early days at Vuitton, they did everything by hand. “You cut out prototypes, workshop them, remake new prototypes. I don’t think people imagine that’s how it’s done,” Ghesquière says. “Delphine was with me throughout. We’d be at lunch with the Princess of Monaco for a Vuitton project on Monday, and on Tuesday we’d be sitting on the floor of the studio cutting out pro-totypes for bags. It was a really fun time.” Ghesquière remembers that they would often be in fits of laughter.

Delphine introduced Ghesquière to the people he’s still working with now—she built the team not only for the sake of the work, Ghesquière says, “but with our well-being in mind too.” It didn’t surprise him at all when Delphine founded the LVMH Prize 10 years ago—her gift for talent-spotting and support was already marked. “It reveals a lot about her—the way she thinks about the future,” he says. Much of what Ghesquière came to understand about Delphine he observed from dressing her. For 10 years, she wore his clothes every day, and told him how she felt in them. Inspired by her, he “changed a thousand things: lengths, fluidity of materials, structure.” Clothes accompany our feelings, he reflects. “If you’re feeling vulnerable you’re going to protect yourself a bit, if you feel stronger you’ll need that less.” He suggests that such an intimate knowledge of this in a CEO will make an enormous difference—it matters that she is a woman. The visitor to Delphine Arnault and Xavier Niel’s home in the 16th arrondissement of Paris is greeted by a rounded entrance hall, and by ground floor rooms with curved edges and generous floral arrangements, leading to giant French doors and a garden. The space offers a kind of instant calm.

One evening last fall, as respectful staff took my coat, Delphine strode forth from the living room: warm, commanding, composed. She had been at the office all day but was now wearing a fluid black suit designed by Maria Grazia: wide silk velvet trousers and a velvet-fronted double- breasted jacket, cinched at the waist but worn with such ease that it could have been pajamas. In heels she was architectural, taller than all of her guests except one: the spirited Ségolène Gallienne, her best friend since the age of five. The two of them look practically like twins, and on the sofa they sat close together, both dressed in Dior, Ségolène’s hands resting on Delphine’s knee as they spoke with relaxed intimacy.

Ségolène and Delphine first met because they had the same swimming instructor in Saint-Tropez, where they have continued to spend summers. Ségolène’s father, the late Belgian billionaire Albert Frère, was the co-owner, with Bernard Arnault, of the Château Cheval Blanc winery. Friends reminisce about nights out with the family: Alexandre DJ’ing in nightclubs, the women fond of tequila shots, Karl Lagerfeld in tow. “She likes to have a good time,” Gagosian says of Delphine, admiringly. Rech fondly points out that Delphine is so disciplined she’ll be with her personal trainer early in the morning, no matter how late she’s stayed out the night before.

While the guests had drinks before dinner, Elisa—who is tall like her mother—darted in and out of the living room in jeans and a green T-shirt. On the walls were works by Cindy Sherman, Takashi Murakami, and Henry Taylor. Throughout the house there were metalwork furniture pieces by the Lalannes, who used to work for Dior in the days of Saint Laurent. Sculptures by Frank Gehry and Ugo Rondinone stood in the garden. (While the Fondation Louis Vuitton collects art, Delphine buys art she wants to live with.)

Mark Bradford, whose monumental painting of an aerial view of Los Angeles hangs above the dining table, is a regular visitor to the house. “It’s very comfortable for me,” he tells me. Bradford, a defiantly political (and hugely successful) artist who grew up in South Central LA, laughs over promising to take Delphine to a soul food restaurant (“She’ll be totally fine!”), and says: “She comes from a famous family. But that doesn’t have anything to do with me and her sitting around talking. You can see the love in her family. Some people you see and they feel like a warm blanket.”

That evening’s 11 guests, who included Eva Jospin and Jean-Michel Othoniel—artists Delphine had collaborated with—a curator, a furniture designer, and the pho-tographer Brigitte Lacombe, withdrew to the small round dining room, dimly lit and spectacularly decorated with an autum-nal centerpiece made of purple calla lilies and russet leaves. The glass plates were hand-painted with lily of the valley, a Dior motif. Circumspect servers brought cured fish, a meltingly good steak, baked apples with caramel ice cream, and a tower of tiny chocolates. The conversation flowed: the exceptional art exhibitions in Paris, homes in the country, the last years of Yves Saint Laurent, Lagerfeld’s insatiable reading habits, the belief that Dior still mattered because Christian Dior himself was a benevolent figure—unlike Coco Chanel.

Delphine and her partner looked at each other indulgently, and there was some gentle teasing across the table. “She’s his biggest cheerleader. He’s her biggest cheerleader,” Bradford says of them. In some relationships, one partner gets all the attention, he observes, but not in this one: “She smiles when he’s talking and he smiles when she talks. I think it’s healthy for the soul. You absolutely see it in them.”

They both stand in the hallway to say goodbye, snatches of conversation still floating in the air as their guests emerge, past the gates and the guards, into the Paris night.