Photo by Raphael Jan Bofill

This year’s Costume Institute’s exhibition is entitled “Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) in New York City. But unlike the previous displays which were fantastic feasts for the eyes, it now employs the keen sense of smell of Sissel Tolaas, a Norwegian chemist and artist in Berlin, who concocted scents out from every strand of the garments displayed.

Before it was accessible to the public, Sissel spent a year studying each item, guided by the lone question: “Can the information conveyed by smell molecule breathe new life into its narrative?”

Furthermore, “reawaken” has become an oft-repeated word in the gallery to emphasize how scents augment the purpose of the exhibit. “The ultimate goal is to inspire a shift from conventional ways of perceiving—primarily through vision—to a more sensory understanding of the world. The sense of smell’s intimate connection to emotions and memories, coupled with its neuroanatomical ties makes it a powerful and overlooked medium for understanding,” she wrote in the wall label. Moreover, she organized an innovative methodology that entails capturing smell molecules from various objects, which led her to constructing a database “replicating and reproducing the recorded smells.”

In the case of the cotton summer dress that Elsa Schiaparelli designed in 1937, Sissel detected estragole, a molecular component in fruits and plants while she found squalene (human skin oil) and caprolactam (the presence of nylon) in the strapless Christian Dior ball gown made in 1953. In the same manner, she has distinguished synthetic fabrics like polyester, nylon, and acrylic in the yellow evening dress Alber Elbaz designed in 2008.

“I’m focusing on literally the molecules emitting from the various items that were used by this woman: the scents of her body, her habits, her culture, her rituals, the food she ate,” said Sissel in an article in the May 2024 edition of American Vogue, which described her as a “pioneer in the work of creating and working the world of smell.” She then continued, saying, “I’m highlighting or amplifying hidden information in the garments. I’m not perfuming spaces.”

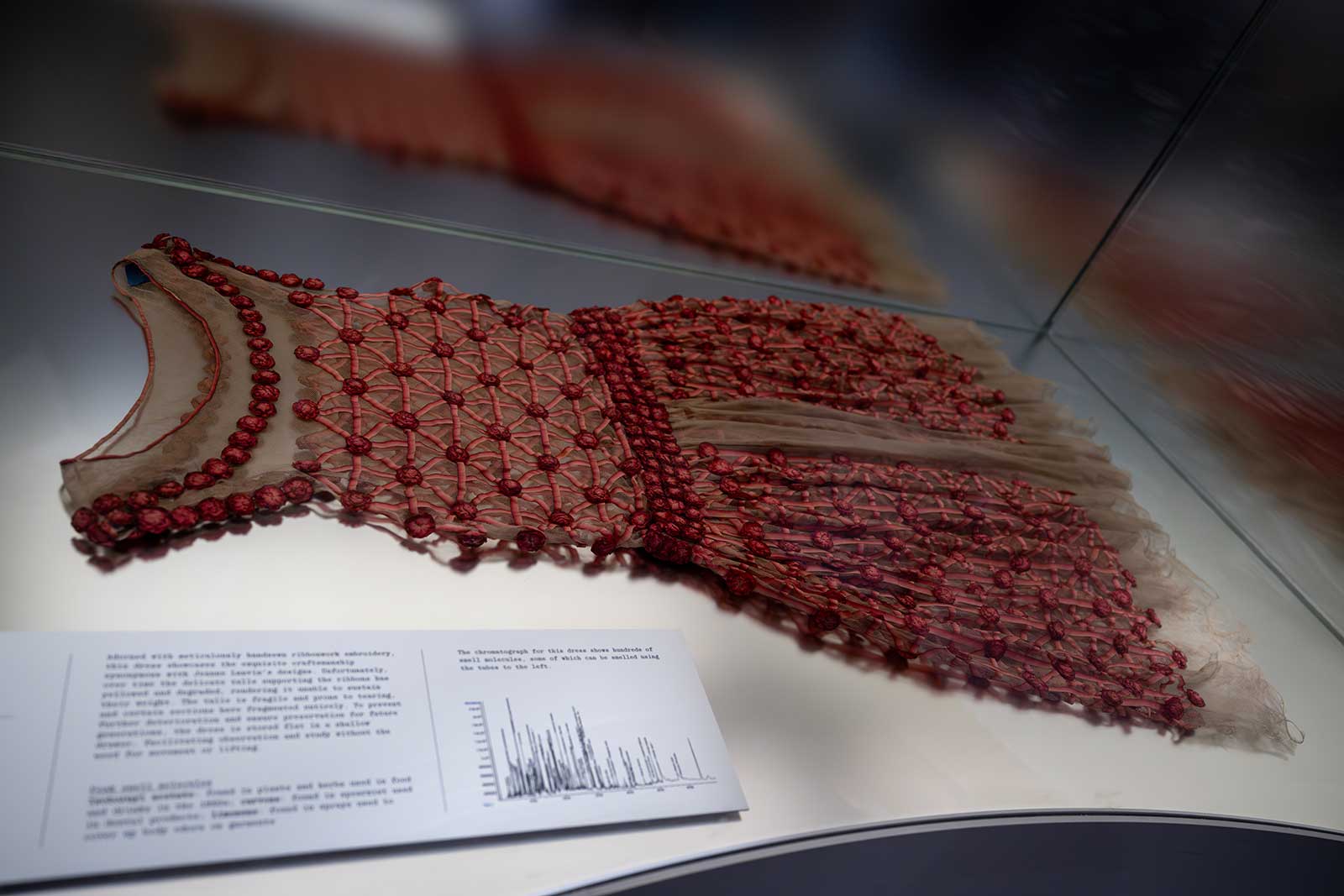

But it is inevitable not to smell the various scents wafting in the air as viewers move around the gallery—like being in a citrus garden at dawn after a heavy downpour. Perhaps, they must have escaped through the acrylic pipes attached to the garments. Visitors then could use these tubes to sniff them as part of the interactive experience.

FASHION AND NATURE

Apart from the multi-sensory properties in this particular exhibition, The Met did not loan from any other institution to complete the line-up. It drew out from its existing collection of over 30,000 objects instead. Common to them are recurring themes like flowers, beads, birds, and butterflies. This includes some century-old garments from the archives, which could only be splayed flat on glass tables because they are too delicate to fit in mannequins. Leading the way are the Charles James Worth ball gown with thick embroidery of sunbeam and clouds circa 1882, the “Roseraie” evening dress Jeanne Lanvin released in 1923, and the 269-year-old floral French “Robe a la Francaise” in taffeta from unidentified designer among others.

“Nature, like fashion, depends on the widest sensory engagements for its fullest sensorial expressions. The comparison, however, does not end with the senses. In many ways, nature serve as the ultimate metaphor for fashion, in its rebirth, renewal, and cyclicity,” reads Andrew Bolton’s, Costume Institute curator-in-charge, note to visitors.

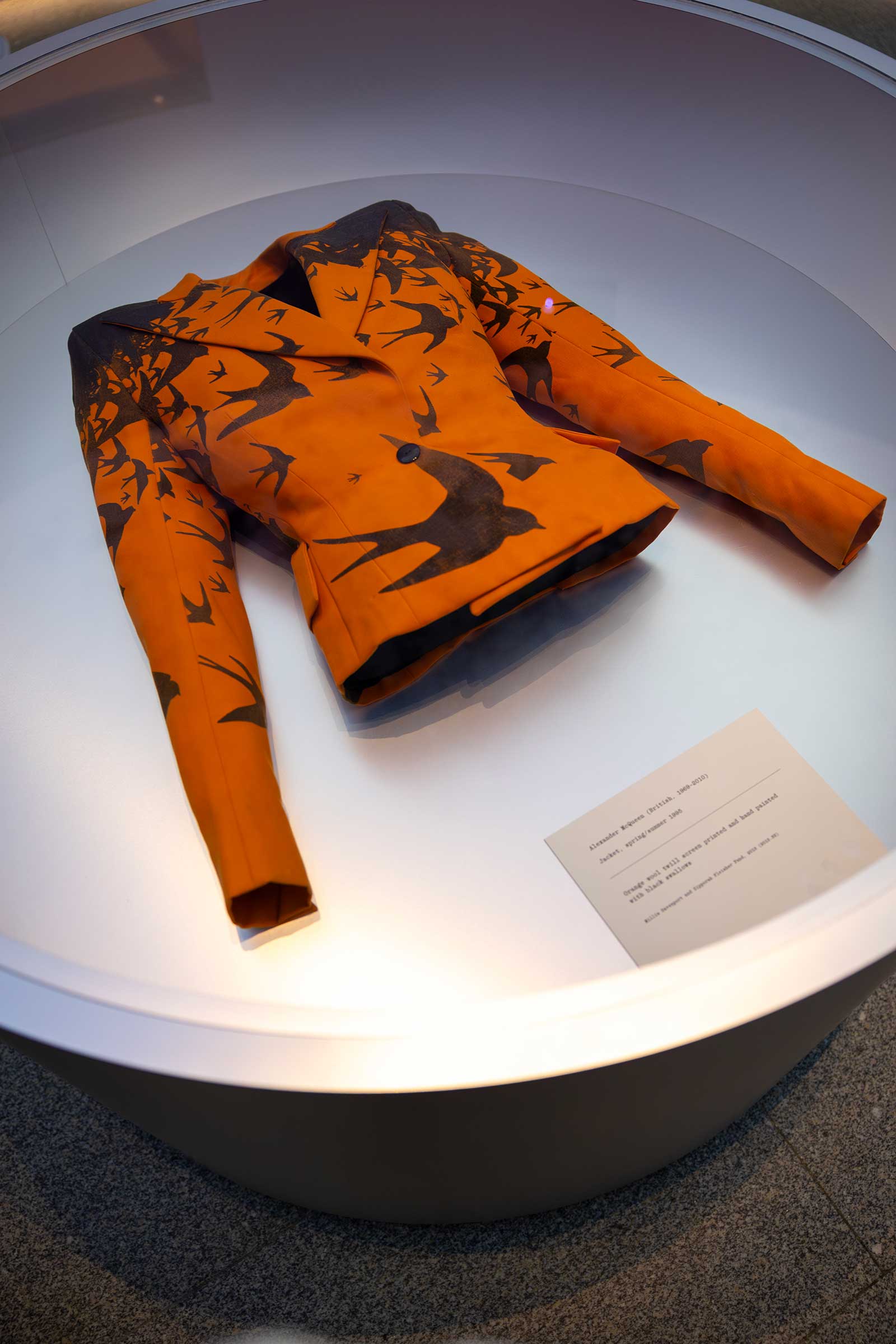

Moreover, Madeleine Vionnet’s handcrafted beadwork was patterned after a family of passerine songbirds, stitched to the black silk tulle overdress. She launched this dress as part of her autumn-winter 1939, a year before the outbreak of World War II. On the other hand, Alexander McQueen’s orange wool twill jacket shares the same features, but his version of the swarm of black swallows—inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s movie “The Birds”—was screen printed.

The sisters Kate and Laura Mulleavy of Rodarte designed a pleated sunflower dress inspired by Vincent Van Gogh’s paintings. Fully beaded garments by Gucci’s Alessandro Michele and Mary Katrantzou depicting birds and flowers greet the visitors upon entry. Notable in this concept, too, is the “monarch” dress created by Sarah Burton during her tenure at Alexander McQueen in 2011 and Iris van Herpen’s “Nautiloid” cocktail dress in an amorphous, free-flowing silhouette.

Other designers also delivered exquisite workmanship and technological advancement like Olivia Cheng, Hillary Teymour, Jun Takahashi, Dries Van Noten, Ana de Pombo, and Martin Maison Margiela to name a few.

Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion is open to the public until September 2.