Photographed by Alexis Dave Co, courtesy of Rajo Laurel

Photographed by Alexis Dave Co, courtesy of Rajo Laurel

Against the sprawl of Bangkok’s skyline, Rajo Laurel showcased his Lahí couture collection on the world stage.

“I love that word inheritance primarily because as a Filipino, I’m a product of everything that has been put in me,” says Rajo Laurel. “I see this collection, I see myself as this living, breathing being that everything that has been put inside me by the generations that came before me.”

His Lahí collection reflects the totality of his universe, drawing on influences from his upbringing, environment, and interests, from national heroes and past designers to his family, particularly his father, the late Jose “Joey” C. Laurel, whose way of representing the Filipino became “almost like a mirror to myself.” The result, Laurel explains, is that Lahí becomes “a direct dialogue between myself and my experiences and the things that I’ve learned as a person as a human being but essentially as a Filipino”.

Presented on January 30 at the Dusit Thani hotel in Bangkok, the 33-piece couture collection was created in collaboration with the Department of Trade and Industry’s Malikhaing Pinoy program. Set against the city’s concrete and literal jungle skyline, the show introduced a distinctly Filipino approach to couture to an international audience, in a similar vein to a Chanel Métiers d’Art show in its celebration of artisans and craftsmanship.

The making of Lahí was as paramount as the outcome. “You know it’s always about discovery,” Laurel says. “We always think that our materials, although humble because we use so much of our hands, this is essentially transformed.” Collaboration emerged as both a process and a philosophy. Two decades after the release of High School Musical, the sentiment of its finale, ‘We’re All in This Together,’ feels uncannily apt as a soundtrack to the collection. “The experience for me was really transformative when I was speaking with the weavers, when I was speaking with my collaborators, when I was speaking with my friends, creating this particular collection.”

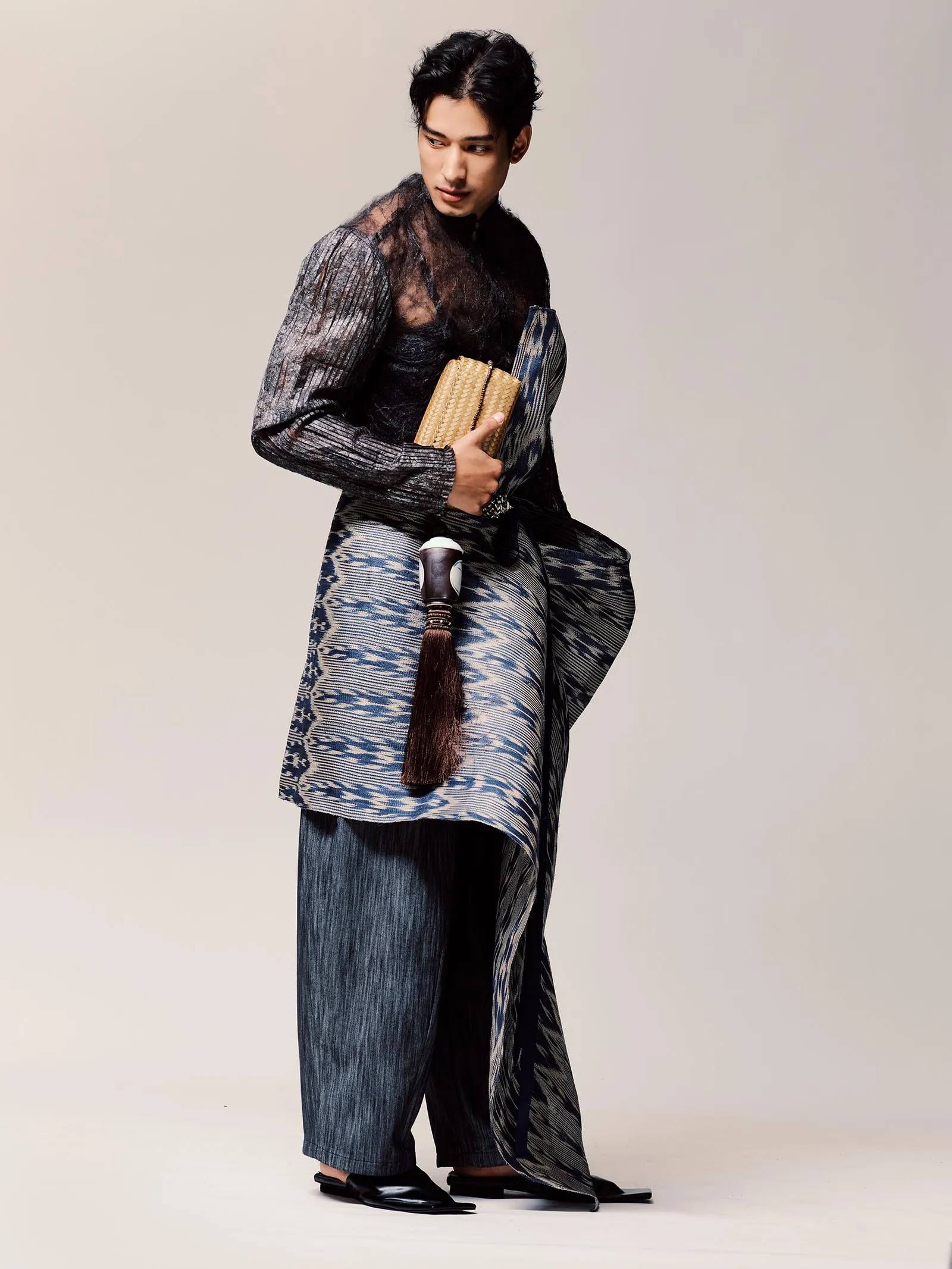

Throughout the collection, Filipino textiles and techniques are pushed and challenged into architectural feats of design, privileging form over function in the service of fashion. Laurel reflects on the power of process: “There is really something special about transforming straw into weeds into pineapple into a thread that becomes embroidery.” For him, this metamorphosis serves as an affirmation. “What really for me was really more like an affirmation of what Filipinos can do with our craft, our skills, and how we can utilise the things around us,” he says. “What makes the Filipino artist and creative intrinsically well is [that] we can truly make beautiful things with almost nothing… how we can create the most beautiful things with the most humble materials”.

Narrative progression has long defined Laurel’s runway presentations, and in Bangkok, this unfolded through technicolor. The show opened in white, transitioned into darker, more austere looks, and concluded in a vivid interplay of color, print, and texture. Traditional references surfaced throughout, not as literal reproductions but as reimagined forms, as if Dominic Rubio’s Tipos de País paintings had slipped out of their frames and come to life: barong-inflected silhouettes, sculptural reworkings of regional dress, and piña textiles pushed beyond their customary ties to formalwear.

Looking to the past also played a pivotal role. Laurel revisited his early works, re-debuting garments that resonate with his current sartorial investigation. “The decision of looking into my archives and bringing it forward essentially was quite simple,” he says, “because I believe that by looking back, that’s the only way you can actually move forward.” A friend’s advice stayed with him: “Why hide the pieces from the past when they are so beautifully made? Show them again…these are stories that are meant to be told.”

Laurel sees the archive as continuity. “I believe that the archives [are] there for a reason, and the reason is that we have been doing this language of DNA, this is the language of our aesthetic, our vocabulary, so to speak,” he explains. “What I’ve done 20 or 30 years ago perhaps is still beautiful today”. Because the show took place in Thailand, several archival garments were remade using locally sourced fabrics. “Because we’re doing it in Thailand, we incorporated a lot of beautiful Thai silk so that conversation is relevant and very much prevalent in this particular narrative,” says Laurel.

Presenting Lahí in Bangkok also carried symbolic weight, seeing the ‘Land of Smiles’ as “a sister nation,” and hopes the collection will spark a “wonderful dialogue” for the future. For him, the goal is to “link these visual clues that connect us as a people as a region and as a race” through beautiful clothes like a Parisian couturier hosting a salon show to a London clientele.

What Laurel ultimately hopes to pass on is collective pride. “I think what I would like to pass on for the next generation of people watching this is love and pride of who we are as a people,” he says. He underscores that Filipino fashion is never a solitary pursuit, and reiterates his Bayanihan spirit of communal unity. “We come [to Thailand] not alone, we come as a community… because fashion is never an island, it’s never been isolatory, it’s not a culture of me, myself, and I, it has always been about we”.