Artists Margaret Gamuti, Mandy Batjula Gaykamaŋu, Margaret Balayu, Helen Milminydjarrk, Abigail Mundjala, Helen Ganalmirriwuy Garrawurra, Valda Malarr, Sabrina Roy, Margaret Rarru Garrawurra, Ruth Ŋalmakara and Susan Balbuŋa, in Yurrwi (Milingimbi), Arnhem Land, Northern Territory.Photographed by Katrin Koenning

Artists Margaret Gamuti, Mandy Batjula Gaykamaŋu, Margaret Balayu, Helen Milminydjarrk, Abigail Mundjala, Helen Ganalmirriwuy Garrawurra, Valda Malarr, Sabrina Roy, Margaret Rarru Garrawurra, Ruth Ŋalmakara and Susan Balbuŋa, in Yurrwi (Milingimbi), Arnhem Land, Northern Territory.Photographed by Katrin Koenning

The experience of watching serrated-edged pandanus leaves transform into colorful fiber—now being spun into baskets, bags, jewelry and mats by the same hands—is nothing less than pure magic.

It’s a small plane ride from Darwin, in the Northern Territory of Australia, to Milingimbi. A bumpy Air North 12-seater flies into a landscape of oval green islands bordered by snaking blue waters. The soil is red, and amongst the trees I recognize something I’m more familiar with in India: tamarind trees, one of the many symbols of the history of trade and exchange—a centuries-old history, in fact—between the Yolŋu people and Macassan traders of Indonesia. The Yolŋu are the people of North Eastern Arnhem Land, where Milingimbi is located. The geographical or linguistic grouping of Yolŋu (which quite literally means “person”), includes close to 20 languages. While I can’t speak to the colonial impulse to group and classify in order to make sense of other cultures, I’m told Yolŋu is a name used with comfort, although specific clan names might be more appropriate. The cross-cultural integration is evident via references to Allah in ceremonial song and photographs of Yolŋu wrapped in batik print dating back to 1913. A Methodist Mission established itself here in 1923 and continued to effectively “govern” until 1974. Fast forward to February 2023 when photographer Katrin Koenning and I took the main road past the one store and arrived at an old Mission earth-rendered building from the 1930s, now the Milingimbi Arts and Culture Center that sits just back from the beach, our structural focal point for the next few days.

The fashion editor in me quite literally gasped (quietly, thankfully) when I walked onto the scene where we met the ladies at the heart and soul of this story, some of them having come in from Laŋarra (Howard Island). It was a picture that looked like it had jumped off the reference board for one of those old Marni resort collections (Consuelo Castiglioni, not Francesco Risso), the kind of print-on-print which even hardened fashion goths like me wanted to run out and buy and pair with an artisanal woven basket. Well, as I live and breathe! Before my eyes the IRL, technicolor, real-deal version: the grande dames of Milingimbi, the women who weave. A mix of master and emerging weavers—the single fiber practice is a 360 degree one set to the rhythm of harvesting, preparing, dying and weaving gunga (Pandanus Spiralis). Whether everyday or ceremonial pieces weaving connects each artist to her ancestors and is imbued with ancestral wisdom which then takes form through each weavers distinct signature. Each bag, basket, piece of jewelry has an artful artisanal feeling only possible when something is truly of the hand. Really this craft cannot be spoken of truly by an outsider, just described, to that point Susan Balbuŋa Warrawarra, a cultural leader and master weaver, tells me: “Weaving is law. Weaving is culture. Weaving is forever, forever, forever.”

Ruth Ŋalmakara, Helen Milminydjarrk, Susan Balbuŋa, Mandy Batjula Gaykamaŋu, Margaret Rarru Garrawurra, Helen Ganalmirriwuy Garrawurra, Margaret Gamuti, Sabrina Roy, Abigail Mundjala, and Margaret Balayu are the artists gathered when we arrive. The ladies are seated cross-legged or reclining on a woven polymat with red flowers on a pale yellow backdrop in the main room, or gallery, of the art center. They are resplendent, dressed in various combinations and permutations of loose-fitting, printed, below-the-knee skirts paired with clashing printed tops in similar fabrics (although some favor perfectly faded T-shirts, as I recall Mandy’s Metallica tee). It’s a dress code ideal for the balmy Milingimbi conditions and perhaps, I’m told, an evolution from the introduction of printed day dresses by Mission wives in the 1930s—the craft of dressmaking and penchant for fabric was taken up with gusto by the Yolŋu women, who are innate artisans. The question of having a choice about covering up…we’ll leave for now. Layered on top and around this sea of paisleys, florals, stripes, and leopard prints are baskets in various nascent stages: pandanus fibers dyed, dried, and placed in bunches on the polymat in hues of reds, browns, and yellows; half-done striped bowls placed under a heavy stone; and an incredible large-scale fringed circular piece folded into a conical shape, nearly completed, in the corner—Susan’s Bamugora, a work half a year in the making but, as I learn, many lifetimes in conceiving.

In wonderfully serendipitous timing, Katrin and I land up at a time when Mandi King, the manager at the art center, tells us the ladies are all gathering to plan the next few months. It is also when Susan is in the final stages of Bamugora, the work that sparked this piece and brought the world of Milingimbi to us.

All the woven works start with the pandanus leaves (gunga)—specifically in the gathering, preparing and dying of these leaves. “Women go out and get the pandanus. Peel them, dry them, dye and start weaving whatever they feel. Authority for weaving comes from mothers, grandmothers, aunties, sisters,” says Helen Milminydjarrk.

Katrin and I head out with Helen Milminydjarrk, Margaret Balayu, Abigail Mundjala, Jack Minmidhi (who works at the art center), and Mandi King to a thicketed area to gather some gunga or, more accurately, to watch on as we slug back water and swat away mosquitoes in what feels like 50-degrees Celsius heat and 100,000 percent humidity. The ladies (including Helen, who is in her mid-60s) effortlessly and powerfully wield long metal hooks to pull the leaves within reach so they can be plucked off the trees to fill large white canvas sacks (printed with Australia Post insignia) and be carried, metal rods in tow, through the bush. Helen tells me they are interested in the soft part of the leaves, not the hard base. The bags are piled into the back of the Utes (utility vehicles) and we head back to the art center. I look over at Margaret Balayu next to me in the Ute and say “Hard work!” (Not that I’ve done any.) She pats my leg and giggles before replying, “Yeah, hard work.”

Photographed by Katrin Koenning

The peeling comes next. This is the preparation of the leaves into long strands that will be laid out to dry. Back at the art center I sit outside with Susan, her daughter Valda Malar, and her grandson Phllip Guyabaka (whom she tells me is always lovingly at her side) on a polymat of blue, this time with yellow flowers, the beach straight ahead of us, where we think we see a crocodile, and the ALPA shop (the only shop on the island, where cooking oil will set you back close to double what it would on the mainland) to the right a few meters away. Susan points to the spiky edges of the pandanus leaf: “Really sharp one. The snakes and critters don’t like it. I don’t know, maybe inside, maybe there’s poison. That’s why the Bamugora protects—it’s like armor.”

First, Susan folds the leaf and runs her fingers downwards away from herself, splitting the serrated edges and pulling them aside, creating long strands of about a centimeter or two in width and at least a meter in length, if not longer. Then, by some sort of alchemy, she splits the leaf and peels it into finer strips, making it look effortless in the way only a true master could. After that, she finishes the strips into equal width, holds them up towards me, and says, “See? Touch it.” The spiky, tough gunga leaves have been transformed into silky soft threads, like fibers ready to be dried and dyed.

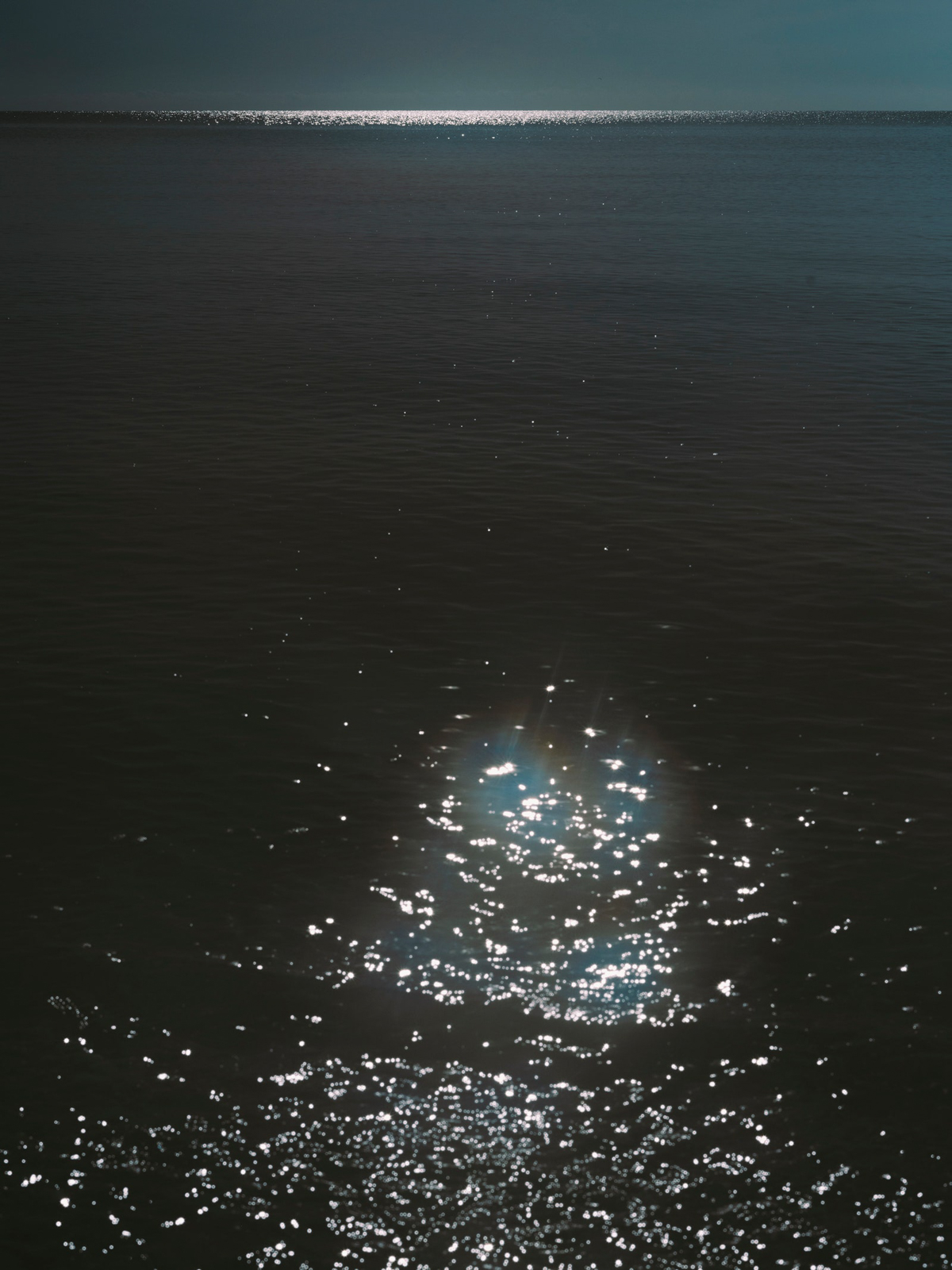

While the leaves dry, we head out on another gathering expedition, this time on the boat with both Helens, Mandy, Jack, and Max Moon, who drives the boat and runs the Djalkiri Keeping Place, a resource for artists to reference the knowledge of their ancestors. The ladies are going to a special spot to collect the roots of the Guṉinyi (Noni Tree) to make yellow dye. The way they navigate the pale turquoise waters is very much an IYKYK situation as both Helens look on, windswept, and point and nod Max intuitively to where we need to be. Helen Milminydjarrk has a cup of grapes in her floral skirt pocket which she offers everyone, Jack is perched on the hull of the small boat cross-legged, Mandy laughs at my wet bum, and Helen Ganalmirriwuy smiles and waves into the camera. It’s fun on the boat. We land on a shelly beach and jump out, Mandy and Helen Ganalmirriwuy at lightning pace, eager to collect shells. Helen Milminydjarrk takes us to the Guṉinyi Tree, machete in hand, and explains that we need the roots for the dye and that the fruit is bush medicine, good for the flu. She then kicks off her shoes to act as a seat, clears an area, and proceeds to use her machete to clear the root and eventually dig it out. Patting away giant ants, I try my best to refrain from stating the obvious again, but hear myself saying, “Geez, Helen, this is tough work!” She laughs as she continues to dig. The tree in question is the size of Helen herself. Jack does the final heave-ho to pull the root free and we see the magnificent, almost-saffron hue peeking out, like magic, from under the brown bark. Piling back into the boat, Helen Ganalmirriwuy and Mandy have also collected a stunning assortment of shells; Helen to make earrings with and Mandy to paint. We returned to the art center, nearly making a pitstop via some mangroves to catch some guya (fish) and maranydjalk (stingray). Next time, hopefully.

Photographed by Katrin Koenning

Photographed by Katrin Koenning

Photographed by Katrin Koenning

Back at the center, piles of the root, leaves, mortar and pestles, dried gunga, and tools are laid out with care in an exquisite still life. I notice Margaret Rarru looking on, inspecting it all closely while sipping on a cup of tea and giving instructions. Rarru, 83, a master weaver and respected elder, pioneered and developed a black dye (called Mol) which she alone can grant permission to use. She tells me via Jack, who interprets, that she learnt weaving from her mother and grandmother (Rarru paints as well), starting at eight or nine years old. The black dilly bag by Rarru wouldn’t be out of place on any runway in Paris; it’s chic as hell and the waiting list is akin to a limited-edition Birkin. The chopped up root, dried gunga, water, and I-don’t-exactly-know-what-else is then carried over by Sabrina and heated over a fire in a big pot, maybe for an hour. This definitely feels like another IYKYK situation. What I do know is that like every stage in this journey, the nuance and artistry revealed is knowledge passed down through generations and generations and generations…and so on and so on. The urgency and absolute necessity of ensuring this passing-on continues was evident in every single conversation I had with both young and old.

“We have to pass it on to the new generation of people. We need to help young people come and work with us and carry on the knowledge of weaving”

– Ruth Ŋalmakara (Chairperson of the art center).

The women now sit together cross-legged inside the center and weave with dyed bunches of fiber at their sides. It’s impossible to describe the experience of witnessing the transformation of the serrated-edged pandanus leaves into colorful fiber—now being spun into baskets, bags, jewelry, and mats by the same hands—as anything but pure magic. Many cups of tea are consumed and Katrin has somehow been given the job of tea runner as she shuttles back and forth to the kitchen. I can see Abigail grinning with a wry smile as she asks for her third serving. I home in on Susan. She faces away from the group, bent over her majestic Bamugora, as she points to the edges where the fringe starts and shows me she’s tying the mat off with a different knot around the perimeter. Susan tells me of her first memory of the Bamugora, one she attributes to sparking her desire to make them: “A long time ago, we don’t know, maybe I was five years old, I saw my grandmother covering herself sleeping under the Bamugora and I climbed inside with her. I remember thinking I want to try this. That’s why I wanted to make Bamugora: my grandmother.”

Working in fashion, an industry completely obsessed with the concept of sustainability and conscious consumption yet seemingly unable to realize them meaningfully, the Bamugora could serve as the gold standard. It is as utilitarian and functional as it is ceremonial and decorative. It is portable, looking at old pictures at Djalkiri, and as Susan explains, it was used by both men and women (although only women can make them), carried around as coverings, as a surface to prepare food, used as shelter, and babies could safely sleep under its protection. The Bamugora, it is said, protects and acts as a repellent to snakes, ants and dangerous animals; they instinctively stay away. It’s so incredibly beautiful seeing it unfolded, with its fringe spread out, like the sun, moving as if alive. It’s not hard to see why gallerists want to rush to display such a thing, but here, wrapped around Susan, Valda, and Roselyn Gamalaŋga, her daughters, and Charlene Madikaniwuy, her granddaughter and Valda’s daughter—three generations of women—it is alive with its true intended meaning and purpose. Susan spoke of weaving being “forever.” I asked her what “forever” meant, and she said: “Forever means all the kids can learn. The future comes from a long time ago passed to a new generation. The past becomes our future. Me, I am talking for generations. All the kids, all the men, all the women—they can learn their culture.”

And she’s passing on that culture to her kin.

Every woman I spoke with, as they all recounted how they’ve learned—by watching their grandmothers, aunts, sisters, mothers, whether they were five or 16 years old—never spoke about weaving artworks for galleries. They spoke of the survival of their culture. While I lack the academic prerequisites to talk about art, I’ll comfortably assert that the majesty of Bamugora by Susan Balbuŋa undeniably warrants pride of place at any of the world’s finest galleries—by anyone’s exacting standards. What is equally undeniable is the salience of the precious culture and law woven into these pieces, the preservation of which is at the forefront of these women’s minds.

One afternoon, I tagged along to drop one of the artists and her daughter home. She and her family live in poverty—indeed I’m told there are very few exceptions to poverty in communities similar to this all around Arnhem Land. I felt equally devastated and guilty, unable to reconcile how the housing of an artwork is given more consideration than the artists themselves. After humbugging Max on the same, he quoted the name of a 1985 album by Warumpi Band, an Aboriginal band from the Northern Territory: “Big Name, No Blanket.”

Photographed by Katrin Koenning

Photographed by Katrin Koenning

Photographed by Katrin Koenning

Photography: Katrin Koenning

Visual Editor, Vogue: Olivia Horner

Head of Editorial Content, Vogue India: Megha Kapoor

This article was originally published on Vogue.

- For These Women of Color, Historical Dressing Is a Modern Art Form

- On The Journey of Healing, Artist Cynthia Alberto Is Ready To Reconnect With Her Filipino Roots

- Bayo Atelier Is About Preserving The Heritage Of Design

- Paris-based Filipino Designer Norman De Vera Celebrates His Creative Journey On The Global Stage