Creations from the new Costume Institute exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art showcase six decades of Karl Lagerfeld’s fashion mastery—while Amanda Harlech remembers working at the right hand of the maestro.

Time passes, revealing details like the receding tide. I can see Karl so clearly—the fastidious way he held his glass of Coca Light, or rippled his fingers through the air as if he were playing the piano when he “love, love, loved” a piece of music or a book I had read that he had given me. We do not change, even if age etches us differently, and the first time I met Karl feels like yesterday.

Karl Lagerfeld was nearly as famous for his look and his devotion to the arts and letters of the 18th century as for his talent as a draftsman. (Among his favorite tools for sketching? Eye makeup from Shu Uemura.) Model Anok Yai looks a bit like a work of art herself in a mohair Fendi haute fourrure cape from spring 2016. Fashion Editor: Amanda Harlech.

It was in the mid-’90s, at one of his notorious parties thrown during Fashion Week for everyone who interested him, any rising star entering the galaxy of his vision. John Galliano had been invited along with some of his team, including me [Harlech worked with Galliano as a stylist and collaborator]. We felt like naughty children in the gilded splendor of his tapestried rooms at 51 Rue de l’Université—l’hôtel Pozzo di Borgo.

I was wearing a bias-cut skirt of paneled diamonds of mousseline that looked like stained glass, and was conscious that I was being looked at from across the room—Karl had a penetrating, fixed gaze from behind a pair of large dark glasses and was seated at a round table in one of his elegant Louis XV chairs. The party thronged around him—moths to the flame, scattering and regrouping at the flick of his fan, dancing across Aubusson carpets thick as moss below candle-lit chandeliers.

Were we summoned—or did we just gravitate toward Karl through the dancers holding glasses of Champagne aloft? My impression was of an emperor at the height of his powers, possessed of an electrifying force that could scan the potential in everyone he encountered. Some time later, when he knew I was struggling with divorce and a difficult contract, he was both courteous as velvet and intelligently generous. “I want to help you,” he said.

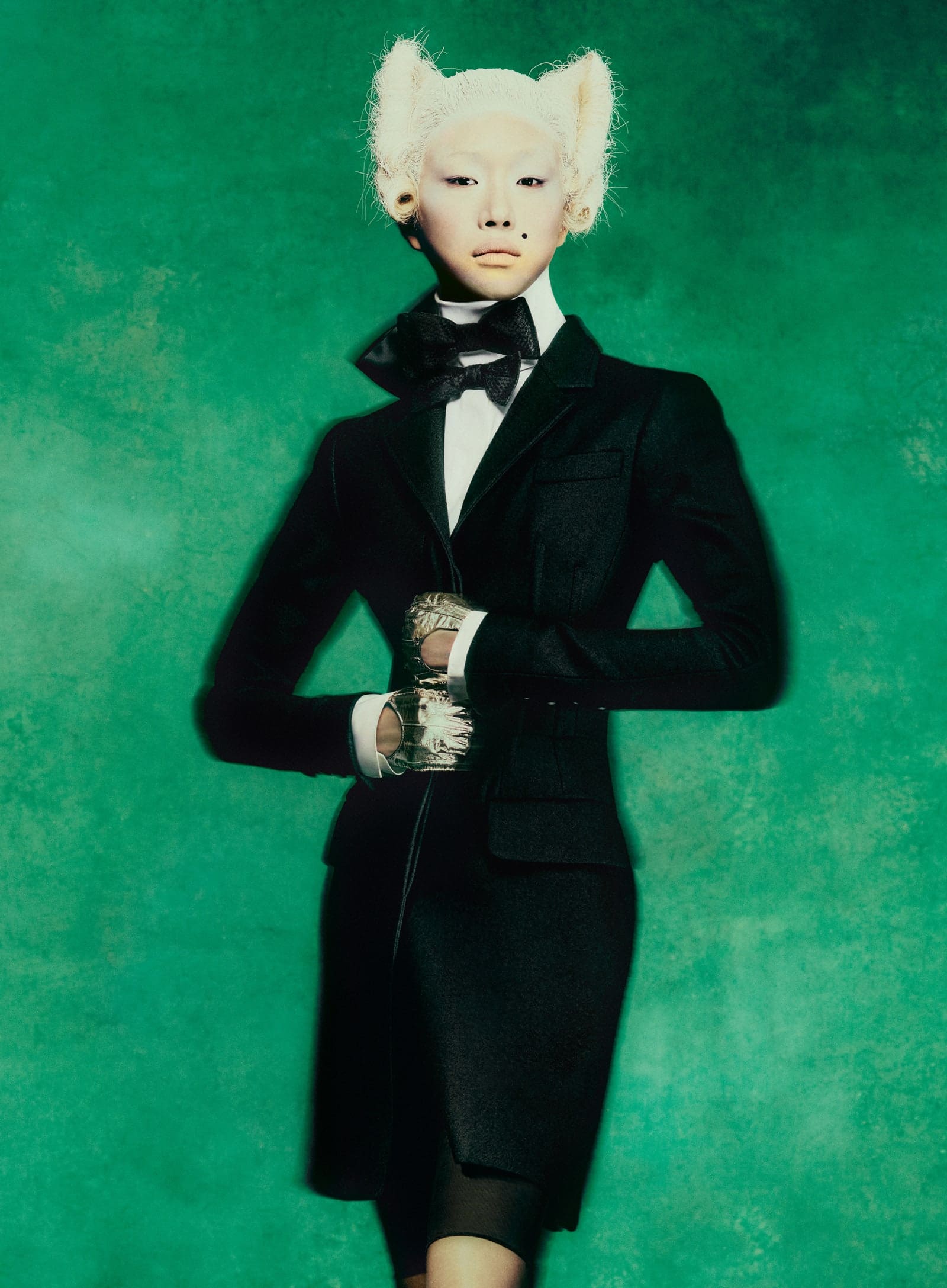

Model Sora Choi is sharp as a tack in a tailored coat, white shirt, and jolly double bows from the fall 2008 collection of Karl Lagerfeld’s eponymous label.

By 1996, I had signed with Chanel and begun working on the January couture collection for spring 1997. The first thing Karl asked me to do was to send him, by fax, the names of the nine Olympian muses—Calliope (epic poetry), Clio (history), Euterpe (music), Thalia (comedy and pastoral poetry), Melpomene (tragedy), Terpsichore (dance), Erato (love poetry and lyric poetry), Polyhymnia (sacred poetry), and Urania (astronomy)—it struck me that this was a secret message contained within his exquisitely evoked collection, later shown at the Ritz, which included three Muse dresses—looks 33, 34, and 35—terra-cotta tulle-embroidered, with black sequins and lace, like ancient pottery.

The difference between working for John and working for Karl was literally the difference between two faiths: One was emotional, driven by narrative and a sensuous exploration of volume and cloth; the other, a brilliant evolution of the architecture of design and the technical innovation of workmanship pitched against an orchestration of historical and cultural references often embedded invisibly into the construction of a garment (or a particular porcelain flower). Karl worked at speed, prodigiously and on many collections simultaneously.

His knowledge of fashion—of the skills involved, of what fabrics would work, and, most importantly, what it was he was proposing through a collection, meant he could make decisions like a Formula 1 driver. Watching him pounce on fabric swatches or an embroidery technique, I was wide-eyed and a bit stunned: There was no hesitation. As Karl often said, there was “no second option.”

Yai shimmers and glimmers in a body-skimming lace piece and shoes from Lagerfeld’s spring 1996 haute couture collection for Chanel.

To mark the 1990 FIFA World Cup, held in Italy, Lagerfeld paid tribute to Fendi’s birthplace with a special collection inspired by the distant past. Yai wears a Fendi dress.

My first day at the Chanel studio beginning work on the fall 1997 ready-to-wear collection was pretty daunting. Everybody had their role in the court—even Madame Pouzieux, who created the braids for the tailleurs on her horse farm far from Paris. There was a girl who just worked on the buttons, and another on the season’s camellia. Victoire de Castellane designed the jewelry with Karl, and Gilles Dufour was head of the studio.

Everything was ritualistic, elegant, and, to my eye, formal—I didn’t really know precisely what I was supposed to do. Instinctively, I just did what I would have done for John—sending Karl a 1920s wedding dress, for example, or making him a scrapbook of images that might inspire him. Karl never told me to stop, but gradually I worked out that Karl already had all his ideas in his head. My role, as he eventually put it, was to be “an outside pair of eyes” that, by virtue of not looking closely at a collection until the weeks before a show, could therefore come in and see whether the dynamic, balance, and proportion really sang.

It wasn’t easy to adapt to Karl’s unspoken expectations. I came from a place where your outside didn’t matter as much as your inside—where self-consciousness can cut across an exchange of ideas. With John, we would all lean across a table of sketches and photographs, swatches, or a twisted garland of lily of the valley. At Chanel, I crossed all sorts of lines when I got up to demonstrate how a jacket might be worn differently—such as across my body or turned upside down. I will never forget the look of horror on the première’s face. (Nobody but the premières or their secondes were allowed to touch the clothes that were being worked on the fitting model.) But I think that’s exactly why Karl wanted me there: He wanted to ease up on the ritual and free up creative possibilities.

Once, when the room was almost airless, heavily freighted with No. 5 and with a row of Chanel tailleurs alongside him at his long table and another row of onlookers standing behind, he got up from his chair and walked out of the door marked “Mademoiselle,” calling me to follow him. “I want you to go back inside and tell everyone who is not directly involved with the creation of this collection to leave immediately…or I will,” he hissed. I walked back in and faced what seemed to me a firing squad. How could I ask anyone to leave? I was the newcomer, the outsider. But I did as he instructed, in my best French—and, to my surprise, the room cleared.

Choi is statuesque in the trompe l’oeil Crétoise dress from Chloé’s spring 1984 collection—one laden with clever riffs on Greek and Italian antiquity. (Once upon a time, as she flitted down the runway, Inès de la Fressange topped off the look with a silver-gilt laurel leaf crown.)

Some 2,000 hours of handiwork by the Chanel atelier and embroiderers from the maisons Lemarié and Lesage went into this organza and gazar haute couture dress for spring 2013, its skirt bristling with lace, tulle, feathers, and bits of pleated muslin.

This was the beginning of Karl’s plan to kick-start the house into a new century. He was recalibrating Chanel, redefining it. Karl didn’t want to be constrained by what had been a success; he wanted to explore what a jacket could be—from the new curving shoulder to the double jacket, or the jacket that was also a dress. He designed the Zen collection, dropping the hemlines to the ankle with flat sandals and a new Chanel chain by the designer Ibu Poilâne.

Significantly, he began to concentrate on a show’s set as a trigger for the design of a collection. Giant chains, an emblematic lion, symbolic gardens, the Eiffel Tower shrouded in mist, and a space rocket all played a part in memorable shows that Karl imagined in dreams and then brought to life at the Grand Palais. He understood that with so many collections, editors and journalists working interminable hours for weeks on end needed to have something impact them in a way that would be instantly and forever remembered. (This same notion also fueled his idea to take the cruise collections and his extraordinary Métiers d’Art collections—which brilliantly showcased the artisan houses that Chanel had rescued and supported—to different parts of the world.)

These shows galvanized the whole studio in a collaged cultural clash between history and the future, with lexicons of references woven into fabrics and accessories. None of us can ever forget Paris-Edinburgh, with the snow beginning to fall as the girls walked through the cloisters of Linlithgow Palace, where Mary, Queen of Scots was born, brooding romance meeting the boyish charm of masculine tweeds—or the emotional Paris-Hamburg show, where Karl evoked everything he loved about a hometown he would never return to.

Big, bold color meets an eye-popping print in Yai’s fetching Fendi dress from fall 2000.

One of the most unforgettable collections was the spring 2009 paper collection couture show, held after the financial crash. In defiance of fear and doubt, as house after house cut back on their shows, Karl pushed in the opposite direction, supported by [Chanel fashion president] Bruno Pavlovsky’s total faith in him. In a white room decorated with giant paper flowers, cutout roses, and camellias, the girls walked down the stairs, their heads decorated with exquisite paper tiaras.

“It all started with a clean sheet of paper,” Karl said, describing his process as a simple creative art—the sketch—that costs nothing but is priceless. Extravagant in detail and workmanship, but as fresh as the rite of spring after the darkness of winter, Karl showed that skill and innovation can rise above any misfortune.

“Karl Lagerfeld: A Line of Beauty,” the exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, examines and celebrates Karl’s outpouring of design over decades at Chanel, Fendi, Chloé, Balmain, Patou, and his eponymous label, Karl Lagerfeld. In a set designed by Tadao Ando, curator Andrew Bolton explores William Hogarth’s aesthetic theory that in an analysis of beauty, the curved lines of the serpentine signify life, while straight lines signify stasis. Andrew, by opening up Karl’s creative psyche, reveals that his myriad emotional and creative currents pulse with energy, whether they be uniform, modernist, masculine—or romantic, historical, or ornamental.

The genius of Karl, though, clearly runs in the fluency of his sketches, which are a focus throughout: Andrew includes a revealing video of Karl’s trusted premières at Chanel, Fendi, Chloé, and Karl Lagerfeld explaining how they could decode his precise sketches to the millimeter.

Karl was very precise—a true Virgo. Virginie Viard, his brilliant right hand at Chanel and now the creative director of the house, would place each sketch, along with its fabric swatches and Karl’s notes, in front of him as the model came before him for the fitting. He would rarely get up, but the model would be close enough for him to see every detail yet far enough away for him to check the proportions. His eye would dart from his sketch to the toile as the premières held their breath—Karl would see in an instant if one fraction of his sketch had not been transposed exactly into cloth.

“I am very sorry, my dear,” he would say to the première overseeing that particular piece, tapping the part of the sketch that hadn’t been perfectly scaled up and reproduced in three dimensions: “The pocket needs to move just a millimeter.” The pocket was ripped off, pinned correctly. “You see? I am sorry, but I am right: A millimeter changes everything.” Karl never lost his temper, never raised his voice, but he was exacting when it came to translating his sketches, which carried the essence of a collection in every pen stroke.

FROM LEFT: Choi has no trouble standing out in a striking (and rather slinky) number from Chanel Métiers d’Art, 2002; Yai wears a richly embroidered organza dress from Chanel haute couture, fall 2006; a sculptural, two-toned haute couture look from Chanel, fall 1991; the dramatic silhouettes of the rococo helped inform the length and volume of this splendid Chanel haute couture dress from spring 2005.

Karl was a lightning conductor—he fed voraciously off positive energy. One of the reasons he could divide himself between collections, photo shoots, architectural projects, moviemaking, and exhibitions was because he gathered gifted and engaged teams around him. He could switch from house to house and from book to book like a blade of light. I remember him asking me once, at the Café Flore, if I had ever tasted a frankfurter. I hadn’t, so he ordered me one, and just as I took my first bite he asked me, in rapid-gunfire succession, “Why do you think Rilke is untranslatable from the German? What is your favorite Emily Dickinson poem?” His mind rolled like mercury.

The Fendi sisters understood Karl’s inexhaustible appetite for the new, to which he could bring his own countercultural or historic references. He would often wonder out loud to me, as the jet landed back in Paris after a fitting in Rome or a show in Milan, how he could divide his creative thought processes so completely. There were no overlaps, no repetitions between the houses: Just as Karl could sense the quality of light in Rome reflected in ancient stones and wide skies, or the refined and elegantly proportioned grays and charcoals of Paris, so too could he extract the distinct energies of each house.

The Fendi sisters would pile his tables with extraordinary artisanal workmanship—having transformed mohair into fur, or turned leather into a totally new texture, like satin, for instance. Fittings at Fendi were wild, exuberant, and full of laughter, his collections rebellious and breathtaking. Karl loved Rome in a visceral, sensual way—I remember him eating a tomato at his favorite restaurant, Dal Bolognese: He threw back his head, holding half the tomato in the air, declaring that this was the sweetest tomato he had ever tasted.

If Karl’s turbocharged energy could almost make a room spin, boredom was something he couldn’t tolerate—his radar could pick up disengagement at 100 yards. One summer in Saint-Tropez, he wanted to have dinner with the boys and me at the VIP Room. This meant driving into Saint-Tropez just before midnight—roof down in the Bentley, hurtling down the switchback lanes, umbrella pines outlined beneath canopied stars, “Bohemian Rhapsody” at full volume. I always thought he was trying to capture the Jacques de Bascher and Antonio Lopez years as we walked along the port, Karl in white jeans and diamonds.

The VIP Room was noisy, even at a long table outside; all the boys were on their phones, and Karl was up the far end of the table, chatting to [model] Baptiste Giabiconi. I just stared into space, the thud of the music pounding through the night. The following morning—I was staying at Karl’s villa—I saw that an envelope had been slipped under my door. Inside, there was a photograph Karl had taken of me the previous evening, with “You look bored” written across the bottom. I learned not to do that again—I didn’t want to be “the cloud that crossed the sun of a perfect summer,” as Karl put it.

For a flock of coruscating jackets in Chanel’s fall 1996 haute couture collection, Lagerfeld called on Lesage to re-create the elaborate Coromandel screens so beloved by the house’s founder.

On Choi’s Fendi shift from spring 2014, a geometric pattern bolts down the front like a racing stripe.

He loved that I lived in the middle of nowhere in Shropshire—maybe it reminded him of his childhood far from Hamburg in the pine forests—and he would send me boxes of books: books about women writers in the 18th century, biographies of Madame de Staël and Bess of Hardwick and Elizabeth Stuart, the Winter Queen, and wonderful books of great painters, particularly Manet, Monet, Picasso, Nolde, and the German Expressionists. He wanted to give “Wuthering Heights” (which is what he called my little farm) a library. Every year or so, he would threaten to visit me—“Where’s the nearest airport with a long runway for the private jet to land? You know Sébastien [Karl’s bodyguard and assistant, Sébastien Jondeau] and I are coming.”

My mind would scramble, and I’d industrially clean the house—Karl was very critical of anyone’s home—dress up all my friends in long white aprons as staff, set-dress the house for a week beforehand, and organize a performance, like jumping my horse over the table outside laid for tea. He never came to stay in the end, which was sad, because he loved the Bloomsbury chaos that he divined from the iPhone photographs I would send him in response to his pictures of a château he had bought in Champagne—or his beloved Villa Louveciennes outside Paris, in which he never spent a single night.

Karl would love to outrun time, stretching days into nights. Yet in the end, time outran him, as it will for all of us. He didn’t tell people that he was ill—only Sébastien. Of course we all knew, but we couldn’t prick the bubble of the lie—we couldn’t confront him, because mysteriously believing he could get better seemed to work. His resistance to weakness was so courageous, it was heartbreaking.

Looking back, I see he did lay out truths, like white pebbles in the darkness, as a path to follow. His last couture—spring 2019—was a collection of all his favorite things in an idealized summer garden with a pool in front of an Italianate villa with curving steps like the ones at Villa Louveciennes, or his childhood home in Bissenmoor. Filled with decorative charm, it was an ode to couture and to luxury—from Madame de Pompadour’s porcelain flowers to the delicacy of tiered and pleated silk chiffon dresses that sang of his genius at Chloé in the 1970s, from the distilled tailoring that spoke of his eponymous label to the more extreme feathered and architectural shapes that recalled Fendi.

At a glance, the Brise dress from Chloé’s fall 1983 collection presents a dazzling spectacle: cascading layers of tubular pearls, sequins, and silver rhinestones against dark blue silk crepe. But peer a little closer, and the embroidered motif reveals itself to be…an open shower head? “I was tired of the usual decorations,” Lagerfeld explained to Vogue Paris that year. In This image: hair, Soichi Inagaki. Produced by Ragi Dholakia Productions. Set Design: Ibby Njoya

This silk muslin and pink organza dress comes alive with a cape of geometric mikado blooms, both from Chanel haute couture, spring 2010.

The night before the show, we finished accessorizing each model—it must have been quite late—and he looked at me and asked what music I would have. It was more a question about what the collection meant to me, and I remembered my most romantic moment with my first-ever boyfriend, traveling around Europe looking at Byzantine churches. We were in Verona and heard the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto being played by a violinist on a rooftop—so I replied, “the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto in D Major.”

“No no no—that’s too obvious, too romantic,” he replied. “What I am thinking of is Das Lied von der Erde.” I didn’t know the piece, by Mahler. As we left the studio, I could see that Karl was exhausted—he slumped in the lift, and had taken off his dark glasses. It was as if he were looking at me from a distant shore, a place far away. He couldn’t get to the Grand Palais for the show—the first he had ever missed. He blamed it on the snow.

When I got home that night, I immediately downloaded Das Lied von der Erde [“The Song of the Earth”], sung by Kathleen Ferrier and Julius Patzak. Mahler composed the song cycle after the death of his daughter, and after being diagnosed with a congenital and serious heart condition himself. The lyrics, from classical Chinese poems, captivated Mahler with their vision of earthly beauty and transcendence. It was as if Karl were showing me that everything he loved would somehow last forever—as if his soul would become one with the everlasting earth.

My heart is quiet and awaits its hour!

The dear earth everywhere

Blooms in spring and grows green

Again. Everywhere and forever

The far horizons are radiant with blue.

Forever… Forever…

In this story: hair, Eugene Souleiman; makeup, Ana Takahashi. Produced by PRODn. Set Design: Ibby Njoya.