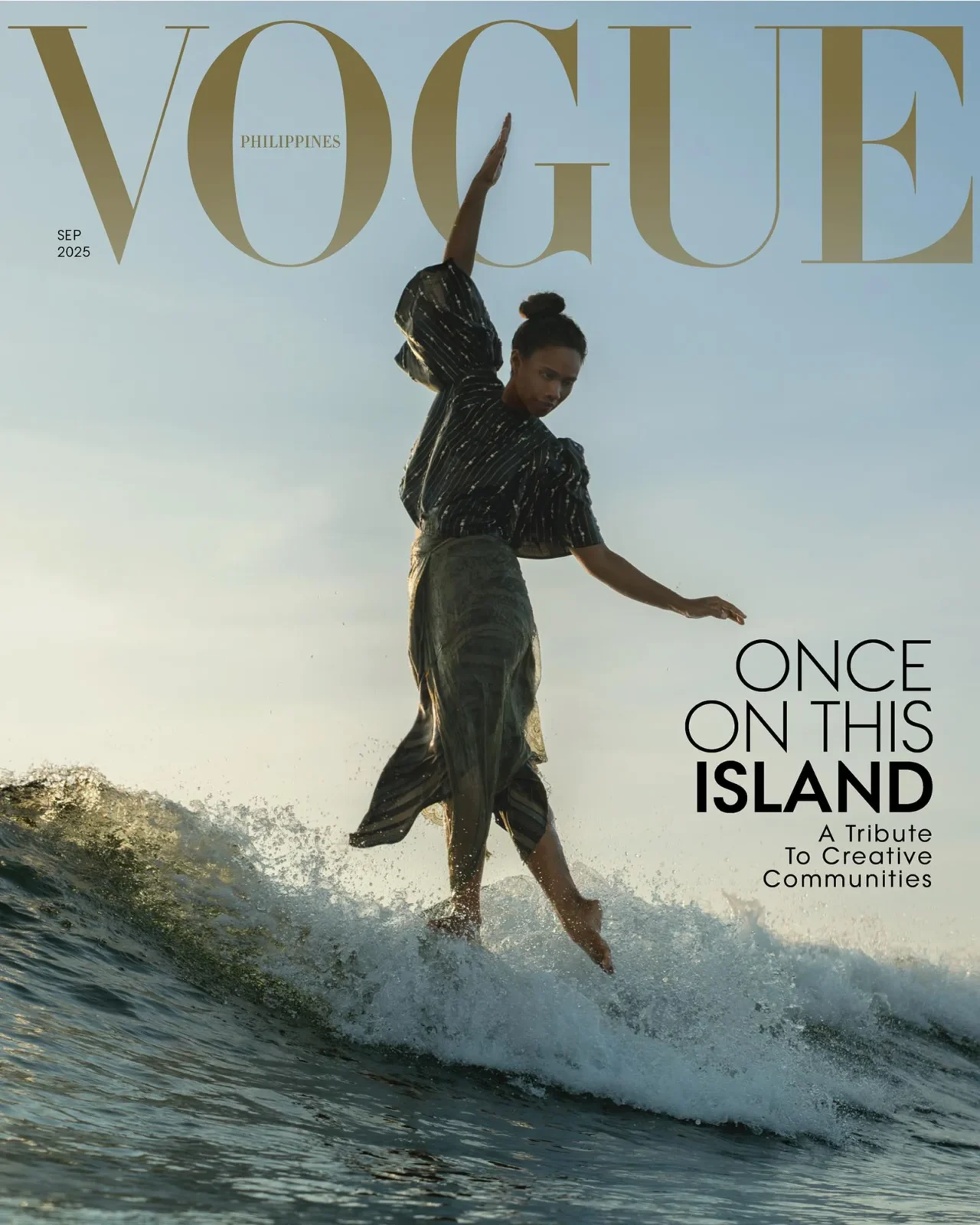

Roy’s custom barongs are all made by Barge Ramos. Embroidered on this one is the Spanish prayer “Nada Te Turbe” or “Let Nothing Disturb You” by Saint Teresa de Ávila, which Roy memorizes by heart and prays daily. Photographed by Max VM for the September Issue 2025 of Vogue Philippines

The first Filipino chief designer at a French couture house, Roy Gonzales talks about finding a home in Paris by way of chance, his time at Cardin and Patou, and a love for both past and present.

It’s a balmy afternoon in June, and Roy Gonzales is beaming, grinning from ear to ear. I’ve been talking to the 82-year-old former designer over the phone since February, following his life in pictures online. I’m not sure if it’s because I’m meeting him in person for the first time, but he seems to carry a different energy now that he’s in Paris.

We’re sitting next to each other along the Coulée verte René-Dumont, a green pathway above Avenue Daumesnil in the 12th arrondissement. Roy seems at peace as he overlooks the city from this viewpoint.

He’s never been here before, but it reminds him a lot of the parks and gardens he used to visit in his youth, when he lived and worked here and needed a quick escape. He was never all that fond of going out and would rather be in a place like this, slow and tranquil, where dappled golden light fell between leaves that changed with the seasons. Back then, you’d find him at Parc Montsouris in the 14th arrondissement, not too far a walk from his former apartment.

This week, I’ve been spending time getting to know Froilan “Roy” Gonzales over coffee and Burgundy wine. So far, I’ve learned that his favorite spare-time activity is mahjong, that he once had a mini pinscher he loved dearly named Chocolah, and that he’s since come to love a shih tzu named Voulezvous.

I learned that he’s fallen in love thrice in his life; the first time was with a man named Jacques, and the second with a man named Marc, with whom he lived in Toulouse for a while. His third past love, and his greatest love of all, was a man named Jean Yves, who stayed with him for 30 years before his untimely passing.

Jean Yves’ last request was to be buried alongside Roy’s mother, because of their closeness, in a cemetery in Parañaque. With the permission of Jean Yves’ mother, Roy fulfilled that promise and visits them regularly, Voulezvous in tow.

The more he shares his life with me, however, the more I’m convinced that there was a fourth instance he fell in love: when he freshly arrived in Paris at 19, wide-eyed and curious about a world that had just cracked open before him.

Roy didn’t know it yet then, but for the next few years of his life, he would keep his days in morning commutes and the meals he made for himself. He’d become a regular at La Closerie des Lilas (“the lilac enclosure”), a favorite too of Sartre, Hemingway, and Stein, where the staff would come to know him by name. And he’d introduce his French friends to adobo, the first dish he ever learned how to make.

Even so, he’s loved this city even before he knew he would call it home. “Paris has always been a place of, you know, l’amour,” he smiles. “It has always been an inspiration for love. Even at a young age, for me, Paris was love.”

His move to the city in 1963 was unplanned. His mother, Josefina “Inang” Paras Gonzales, only imagined he’d stay for a year after completing a certificate at L’École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture, or the Institut Français de la Mode (IFM), as it’s known today.

Inang was the sole inheritor of her mother’s business, the House of RT Paras, recognized as the oldest fashion retailer in the Philippines before it shuttered before the pandemic, and when she was at the helm, it was at the height of its popularity. She often dressed Manila’s high society in their finest: beaded and printed daytime dresses, meticulously tailored suit sets, and ternos for evening and special occasions.

She knew Roy would inherit it after her someday, and decided that his having a Paris education might pique their clientele’s interest further. It wasn’t that they needed it, but it wouldn’t hurt. And so Roy went, if only to provide her that comfort, then only a sophomore at Ateneo de Manila University for an economics degree he had to leave behind.

The following year in Paris, he didn’t expect to graduate at the top of his class at IFM, or that one of his professors would urge him to present his final collection to Pierre Cardin, then one of Paris’ buzziest couturiers. What Roy expected the least was to walk out of his atelier with a signed contract in hand, then go on to become the sole designer to work under him at only 20 years old.

“When I did that, I didn’t even think of getting work,” he chuckles to himself, recalling that he only went in the first place because it meant a chance of getting a glance at some of the models he idolized from all the magazines he read.

Roy decided to tell his mother in person to spare her some of the heartbreak. She wanted to celebrate his graduation by traveling with him across Europe before going back to the Philippines; by the time they reached Rome, the final stop on their tour, he finally broke the news. “I said, ‘I can’t go home with you. I have a contract with Cardin,’” he pauses. You can only imagine what would happen next. “Niagara Falls, my mom.”

He joined Cardin at a point in time fashion called “the pause.” “That’s when we prepare the next collection,” he explains. “I was the personal assistant of Monsieur Cardin himself. I saw everything he did, and learned a lot about the construction of a dress, pants, a jacket.”

This was when the maison was cutting mock-neck collars on bonded jersey, patterning experimental geometric shapes into his designs, and working with newly developed materials like PVC and acrylic. Looking back at his time there, the most valuable lesson Roy learned was the ability to turn things on their head; it was a seam “where it shouldn’t be,” or a pant silhouette imagined anew each year. One time, Cardin advised Roy to put a shoe on his head to wear as a hat. “It was pure creation with Pierre Cardin,” he tells me, and his sentiment rings in the air.

In 1976, Roy went on to design under the creative direction of Angelo Tarlazzi at Patou, a training period cut short when Tarlazzi abruptly left the following year. Suddenly, the reins of the fashion house, established in 1914, were left to him. Were it anyone else, it might have been too large an ask. “I don’t know why I became very brave!” Roy exclaims. “They asked me if I could do it, and I just said, yes, I’ll accept. And I did collections until 1982.”

Those years were some of the “most exhilarating” of his life. “It was here [at Patou] where I expressed myself in all the collections I executed,” he says.

Roy did four collections, two couture collections and two ready-to-wear collections, every year for five years. It was nonstop work. He established his routine then: a cup of coffee, the commute to that 18th-century building on rue Saint-Florentin, a meal with his coworkers, and then he’d sequester in the atelier (which at that point had decor left untouched since Jean Patou himself ran it) to sketch, often for hours on end.

“All I did was create, create, create,” Roy recalls. “And the business [side of things], as long as they kept me, I knew [pieces] were selling… You know more or less what some people like. You learn that.”

You must have been very observant, I comment. “You had to be. Because in what I do, I have to be very observant in what people want, what they need, and of course, it has to marry what I [want to] create,” he explains, then seemingly smiles at a specific memory. “I’m maybe creating something that they find crazy, but later on, they’d say, ‘Well, it has logic, when you make it like that.’”

There were times when his skirts referenced the cut of a saya or were draped the way an alampay would fall. “I’ve been influenced a lot by our traditional attire from the beginning,” he says. “Then later on, I started becoming more French. Because the Parisians wanted to please the customers, and our customers were international, from Japanese to Americans to Europeans.”

To him, his design signatures were about bridging that gap: between what he knew and what he came to learn, between “classic” and, always, “a twist.” “Just because it’s wearable,” he continues, “it doesn’t have to be boring. I wanted my designs to be exciting.”

The creative director role as we know it today hadn’t been established yet back then. But in his time at the fashion house, he checked off all those boxes: casting and styling his shows, making sure things sold. He secretly loved that part; it was never really a measure of success to him but a way of checking he could pinpoint what a woman would wear to feel attractive, and perhaps, to feel transformed.

At this point in his life, Roy doesn’t remember how he managed to balance it all, just that he did. “It’s a good thing the Lord gave me the ideas in my head,” he smiles. “I was able to do all of those collections.”

It’s funny, though, because he never once thought for a second that he was making history for the Philippines, becoming the first couturier at these storied fashion houses. But I learned that he did that intentionally, and he thinks young Filipino designers should do the same. “If you get very proud, I think that stops you from getting ideas. Because you’re so proud, you say, I’ve arrived here, I’ve done it. [But] you never ‘arrive.’ You just go on and on and on.”

He adds, “Even now, if you asked me, I wouldn’t say I’ve succeeded.”

“Really!” I can’t help but exclaim. “Why?”

“Because I still have ideas!” he beams. “I still have things like that going on in my head.” And I suppose, for someone like Roy, the love of it all never truly goes away. It’s a continuous, pulsing energy that began beating in his youth, when he was a young boy who often peeked over his mother’s sewists’ shoulders to ask whether the fabric they were using was silk or chiffon.

“When I’d come home from school, I didn’t ‘play.’ I played around in the shop. I played with the materials. I was always with the seamstresses, asking them, ‘What are you doing? Why are you doing that?’ You know, I bothered them,” he squints, eyes mischievous. “Nakukulit, but you know, they liked me because I was a small child asking questions. I was already interested at that age.”

I still see that boy in him now. In casual conversation later on, he tells me that his favorite story is Cinderella because, out of all the characters in fiction, he resonates with the Fairy Godmother the most. Is that why he loves what he does? Because fashion is a means for transformation?

“To the point,” he says simply. “That magic comes from my pen to the paper where I design.” Still, he’s too humble to admit he could lift any sketch from the page and carve it out with his hands, the ability to make magic tactile. Roy laughs to himself suddenly. “Once, we had this funny thing happening with our premiere,” he starts. “She told me, Roy, it’s impossible to use that material to make a bolero. [But] it wasn’t impossible. So I draped it on the mannequin and I said, ‘There’s your bolero.’”

“I’ve learned that everyone wants to live on top of the mountain,” I read to myself, “but all the happiness and growth occur when you’re climbing.”

It’s an excerpt from the poem “I’ve Learned …” by Andy Rooney. Right now, it’s early morning in Paris, and Roy and I have a reservation at La Closerie des Lilas later tonight. The poem is the first thing I see today; he texted it to me late last night, hoping I’d enjoy it.

From my time with him in Paris, I’ve learned plenty on my own, too: that a building can spark inspiration for a drape, pattern, or fold; a shoe can be a hat; and anything can be turned into a bolero. I’ve learned that curiosity can lead to discovery, and humility defines lasting success. I’ve learned that any place can be a home, so long as you choose to see it that way.

Above all, from Roy, I’ve learned that to go on and on and on is to believe in a world untethered, only as open and giving as you will yourself to be.

By RYLÉ TUVIERRA as told to CHELSEA SARABIA. Photographs by MAX VM and Kim Santos.

- Four Pioneers of Philippine Fashion Image-Making Look Back on an Era They Helped Define

- Inside the Learning Grounds of F.A.B. Creatives, “Everything Within Reach of Our Senses Can Be an Inspiration”

- The Members of Aktor PH Take On Their Most Meaningful Role Yet

- Lady of the Hour: Cinematic Stills Reimagined in Filipino Grace