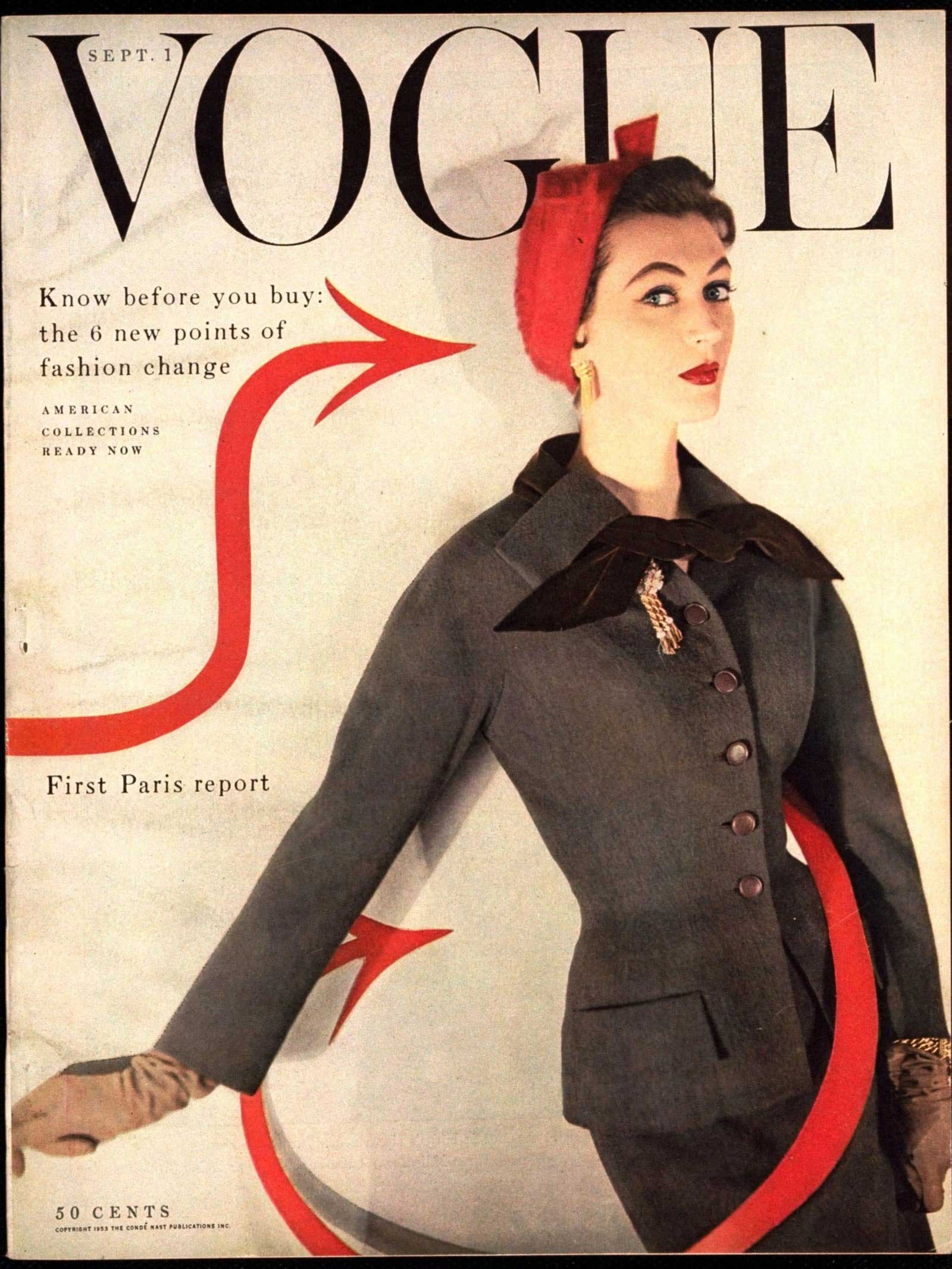

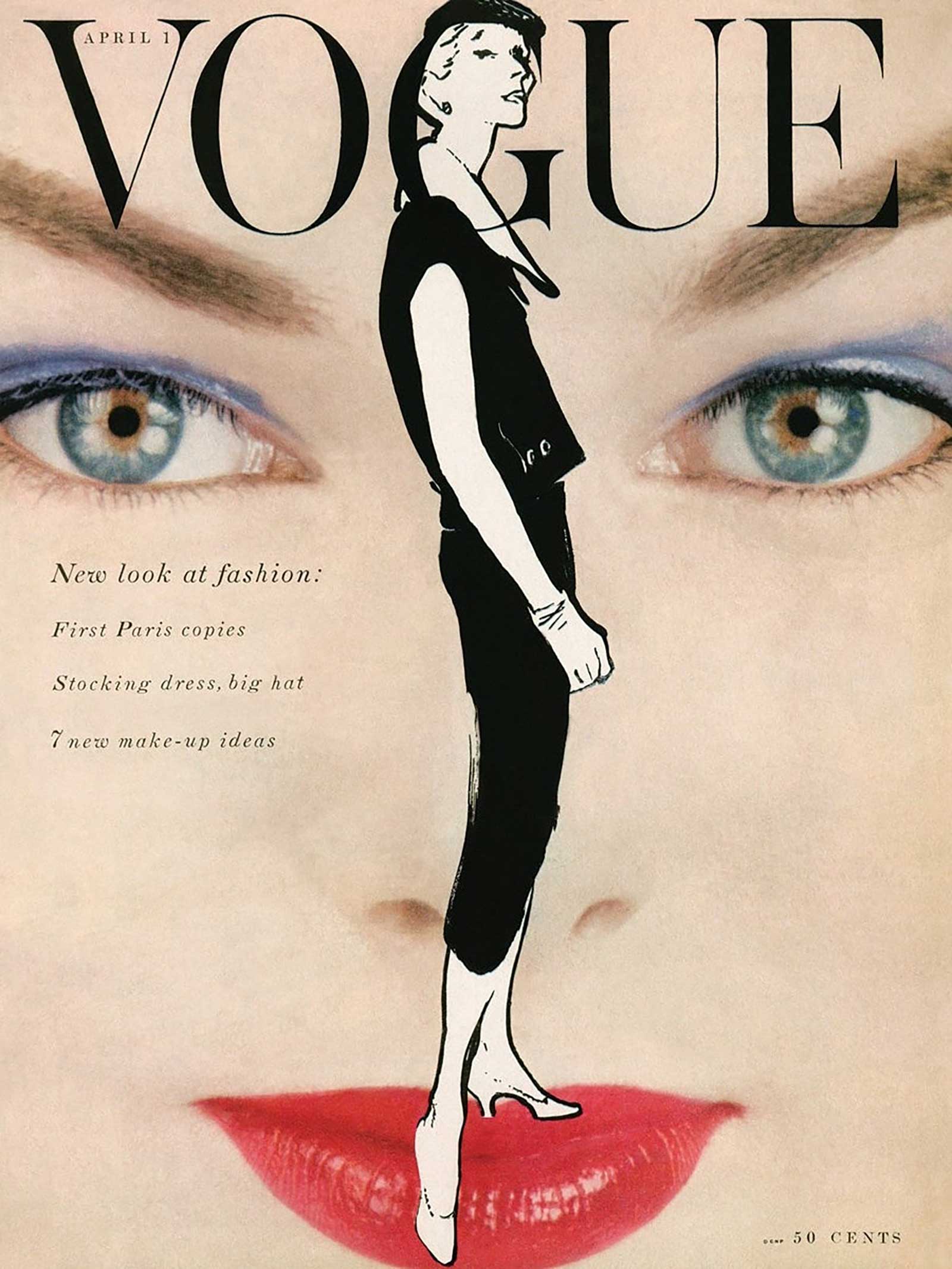

Photographed by Frances McLaughlin-Gill, Vogue, November 1, 1952

Not to split hairs, but the look of the 1950s was really born a few years prior. When academics talk about 1950s fashion history, the era is usually defined as 1947-1957—and just so happens to coincide with the years that Christian Dior operated his fashion label. After the designer’s premature death in 1957, 21-year-old Yves Saint Laurent took the reigns at the Dior, closing out the decade with his beatnik-inspired collection of 1960.

During this infamous era, fashion reached its most glamorous height, reflecting the world’s eagerness to leave wartime rations and austerity measures behind. The world was in dire need of beauty and the fashion industry delivered—and then some.

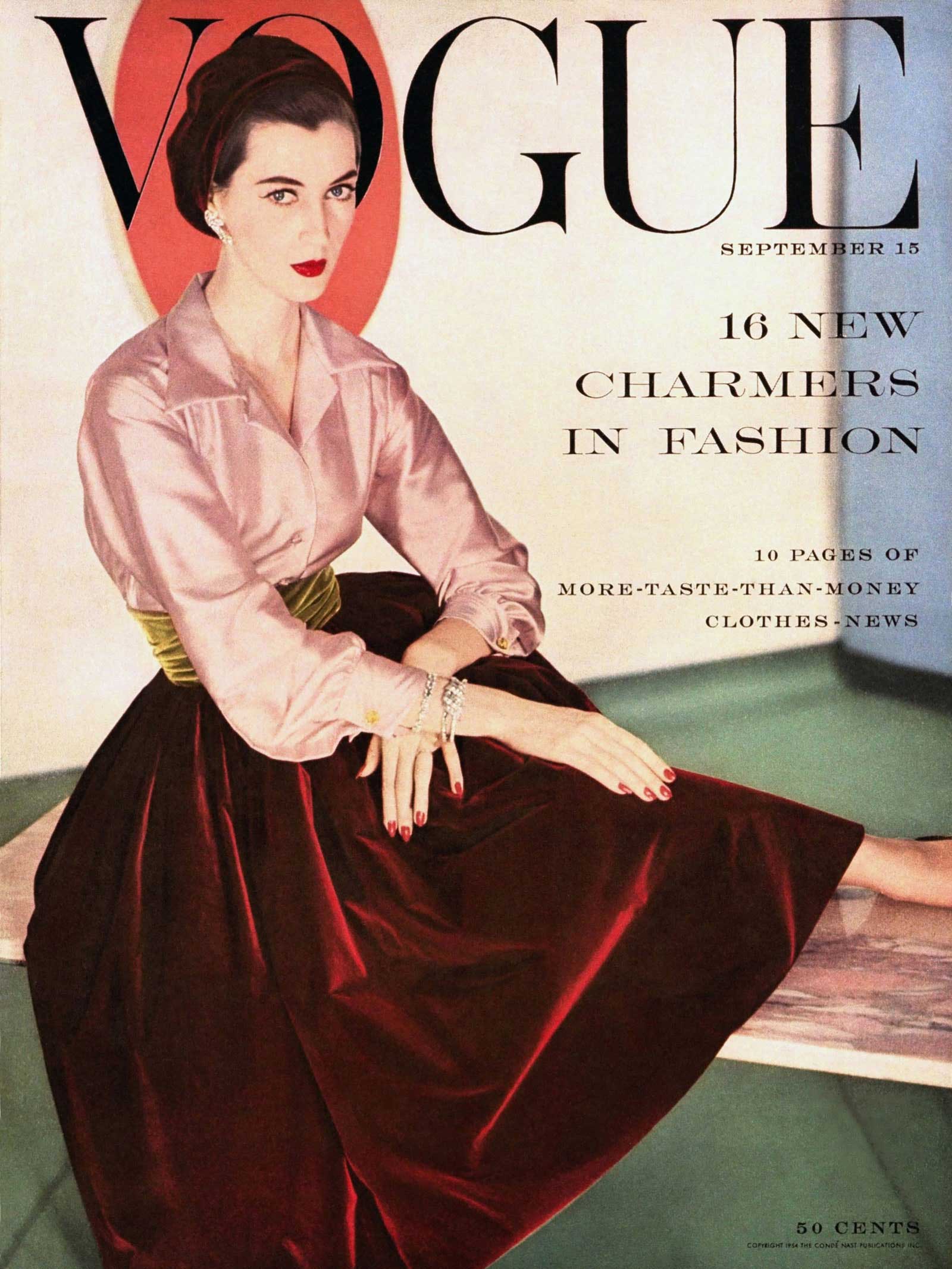

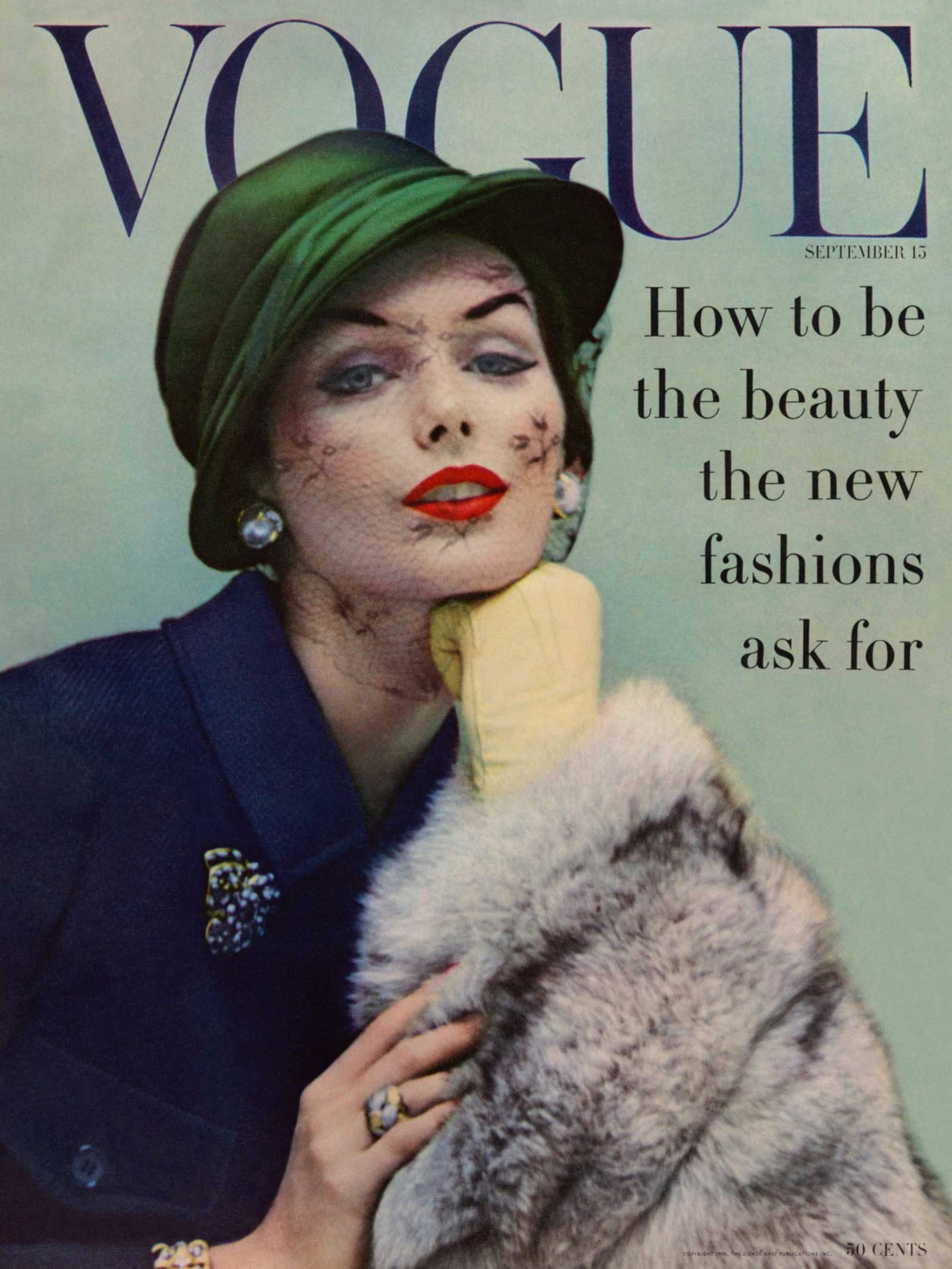

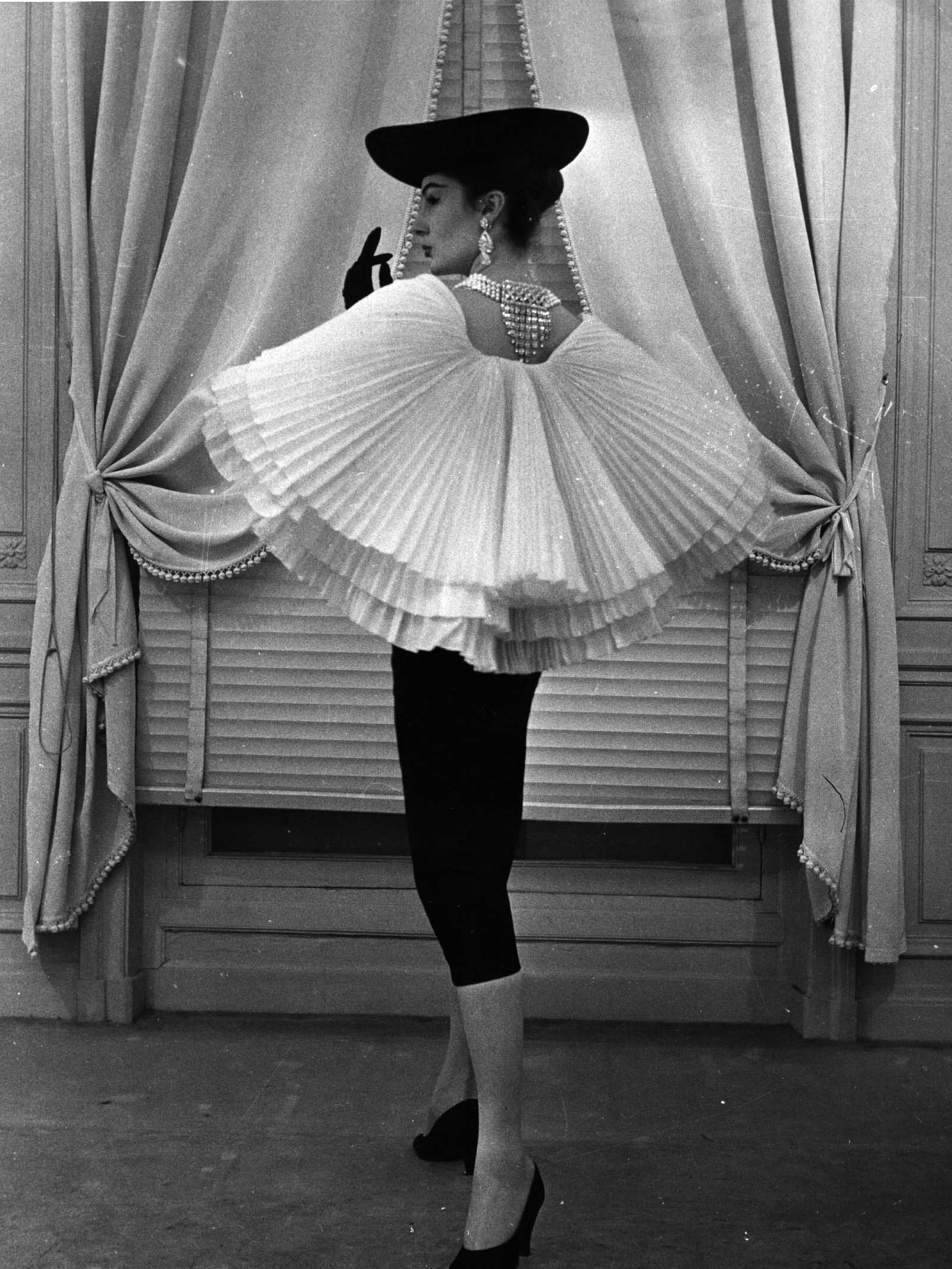

Celebrating the end of World War II meant celebrating women as women, capital W—with nipped waists, voluminous skirts, impeccably made-up hair, and accessories for every possible occasion. For better or worse, the coordination of hats, gloves, and handbags—the not-a-hair-out-of-place standard of the era—gave women innumerable fashionable and cosmetic diversions. The decade might be remembered as a step back for women, who chased heavenly ether-levels of beauty, but boy, did it deliver some fabulous looks.

Women’s Trends of the 1950s: The Hourglass Silhouette Reigns

Dior’s New Look Leads

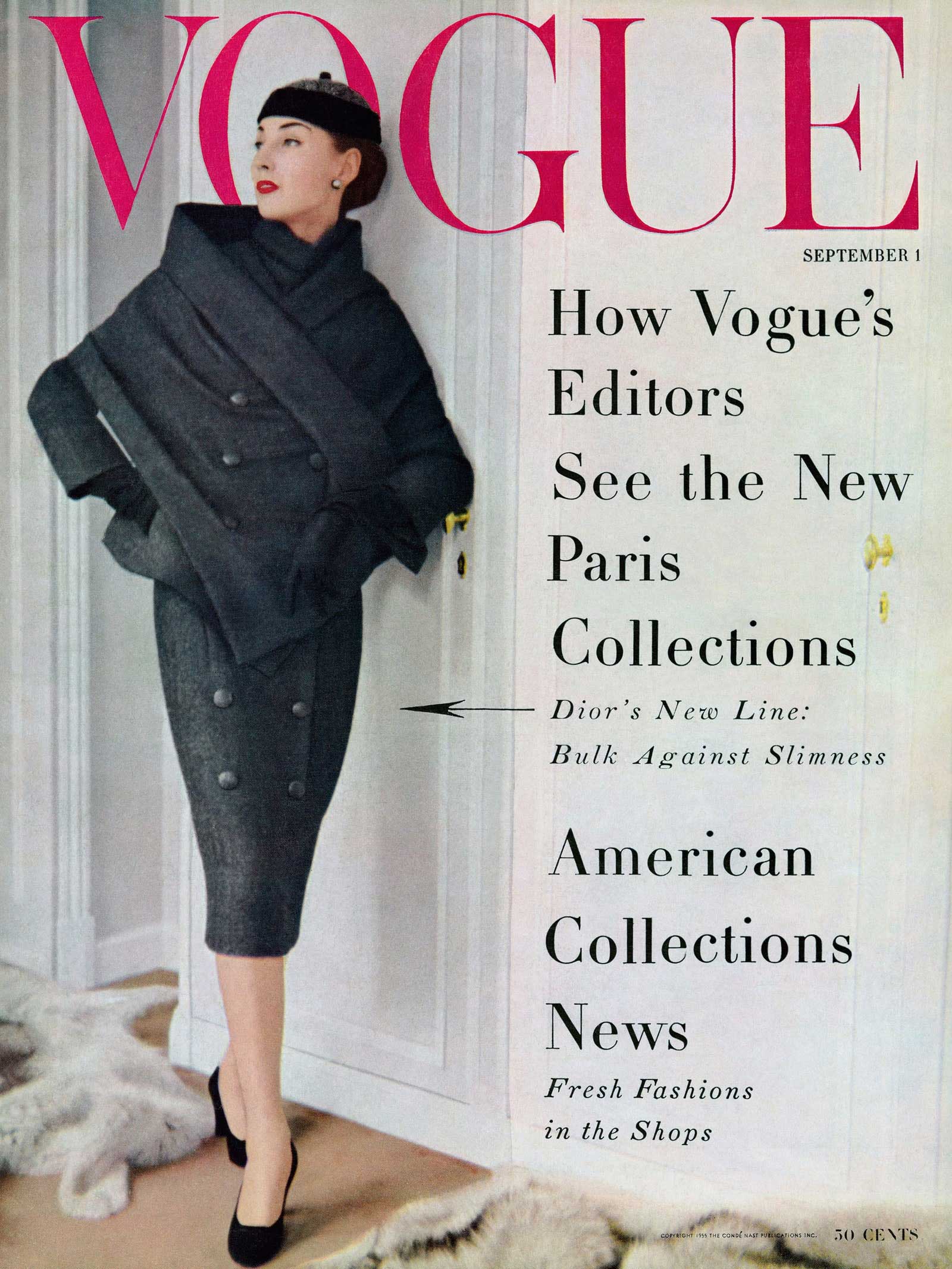

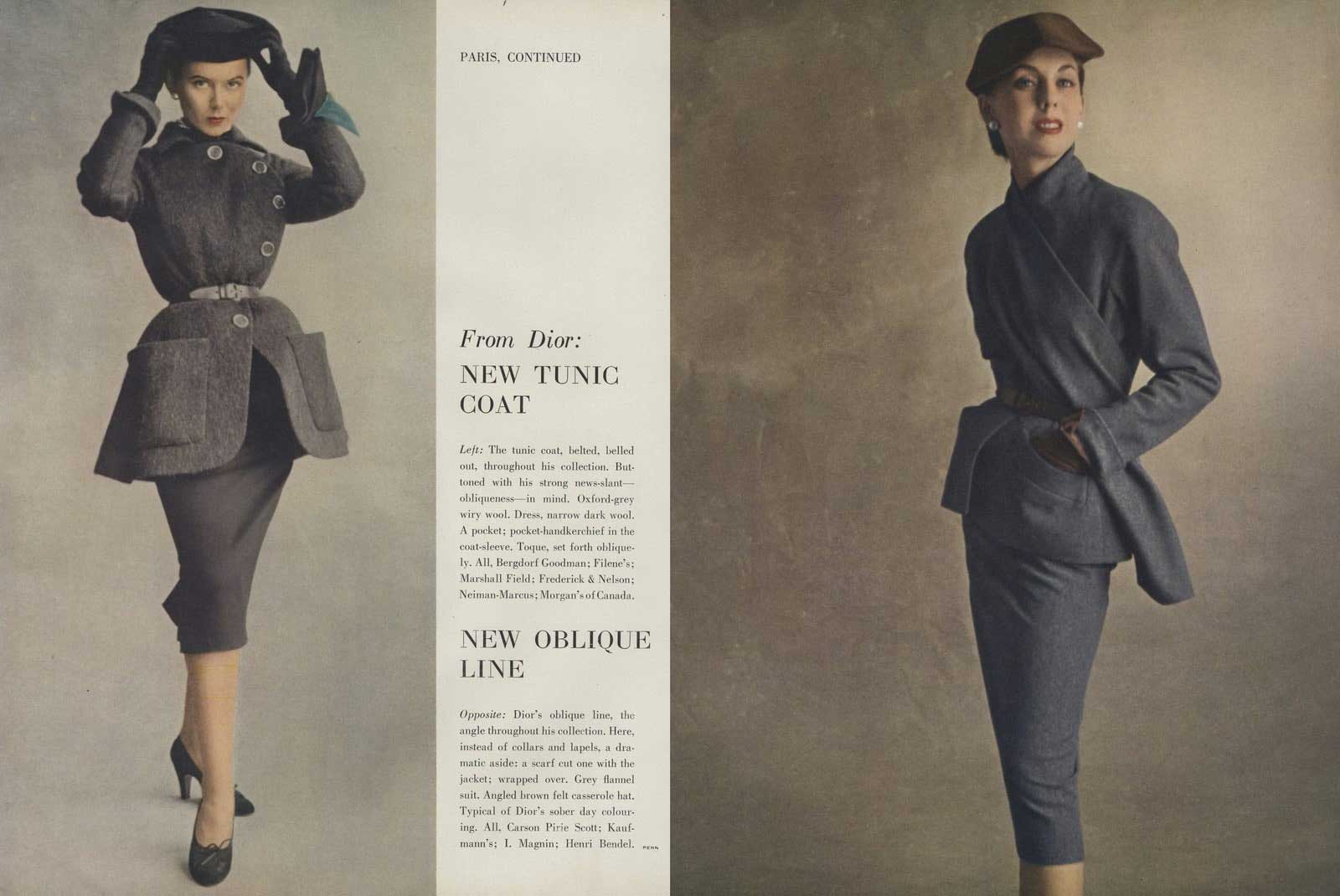

The silhouette put forth by Christian Dior in his 1947 New Look Corelle Line collection dominated the 1950s. The nipped-in-the-waist dresses, which exaggerated the feminine silhouette, represented a rapid-speed swing of the pendulum; in the 1940s, masculine silhouettes with crisp wartime shoulders and slim hips ruled. Now, shoulders were softened with padding that rounded them, waists were snatched and shrunk to Victorian proportions, and hips were exaggerated with tulle and crinolines that added bulk. The goal? A supremely “feminine” silhouette.

Vogue’s Paris Collection report from the March 1, 1952 issue put it succinctly: “It begins at the waistline. The waist is what catches the eye right away. It’s newly high, it’s newly low, or it’s both.. but it’s always there, always stressed, and because that’s the case, fashion looks more feminine than it has in years.”

The aesthetic is famously considered to be led by Dior but all his contemporaries were on board and championing the look in their own ways. Balenciaga, Balmain, Jacques Fath, Hardie Amies, and more were churning out ultra-glamorous, highly feminine dresses for most of the decade.

Couture’s Golden Age

Paris Rebounds After its Occupation

“The Chambre Syndicale de la Couture has requested that all publications showing Paris models from this collection publish the following line—to apply to all models shown: ‘Copyrighted model—reproduction forbidden.’ Of course, this does not apply to shops and makers who have bought the original models.” This PSA was printed in Vogue’s September 15, 1951 issue in “Paris Collections Note.”

In other words, the designs Paris couturiers were steadfastly churning out after their city rebounded from its devastatingly deballasting German Occupation was feeding the world’s insatiable appetite.

A black market of Parisian couture knock-offs flourished and individuals with photographic memories were even sent by American department stores to the Parisian press for weeks to quickly sketch what they saw to be immediately reproduced.

Today, fashion history scholars look back at the ten-year span of 1947-1957 (the 10 years in which Monsieur Dior was designing) as Couture’s Golden Age. It was extravagant clothing at extravagant prices for extravagant living and couturiers were fashioning the moment. By the end of the decade, youthful fashion and the Space Age aesthetic would replace the utter prettiness manufactured during the golden age when designers employed a high degree of savior faire as though pushing the limits of beauty.

A Straighter Silhouette Emerges

Chanel Slips Back into Fashion

Half a decade into the New Look, a new silhouette was brewing. Fashion can only remain in fashion for so long. The rigid hourglass began to soften and become less insistent. Dior introduced H-lines and Y-lines. If the decade started off with two stacked inverted triangles with touching points, it ended with the prevailing silhouette of an upside-down triangle—a trapeze shape or A-line silhouette that skimmed away from the body.

By 1958, hemlines were creeping up, and skirts were flaring out, paving the way for the introduction of the miniskirt—but not so fast. In the meantime, designers were having fun with refined, linear silhouettes that put less emphasis on the waist and more on unbroken lines with an architectural flair.

This easing up was championed by Chanel, who, after laying low after the war for the sake of her own spotted reputation, made her grand return on February 5 (her lucky number—a date she always preferred to show on) in 1954. She showed suits in springy jerseys cut in straight, unfussy lines.

Bombshells and Bad Boys

Marilyn! Grace! Audrey! Dorothy! James! Marlon! Elvis!

Though Hollywood figures had always impacted popular culture, the 1950s saw leading men and ladies transcend to fashion gods and goddesses. The adoption of color film had much to do with the sartorial showcase offered by these pictures—that, and the fashion prowess of costume designers like Edith Head, William Travilla, and Orry-Kelly.

There was Audrey Hepburn in Givenchy in Sabrina (1954), Marilyn Monroe in William Travilla’s creations for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), Grace Kelly in blue gossamer gowns by Edith Head in To Catch a Thief (1955), and Dorothy Dandridge in Mary Ann Nyberg’s colorful creations for Carmen Jones (1954).

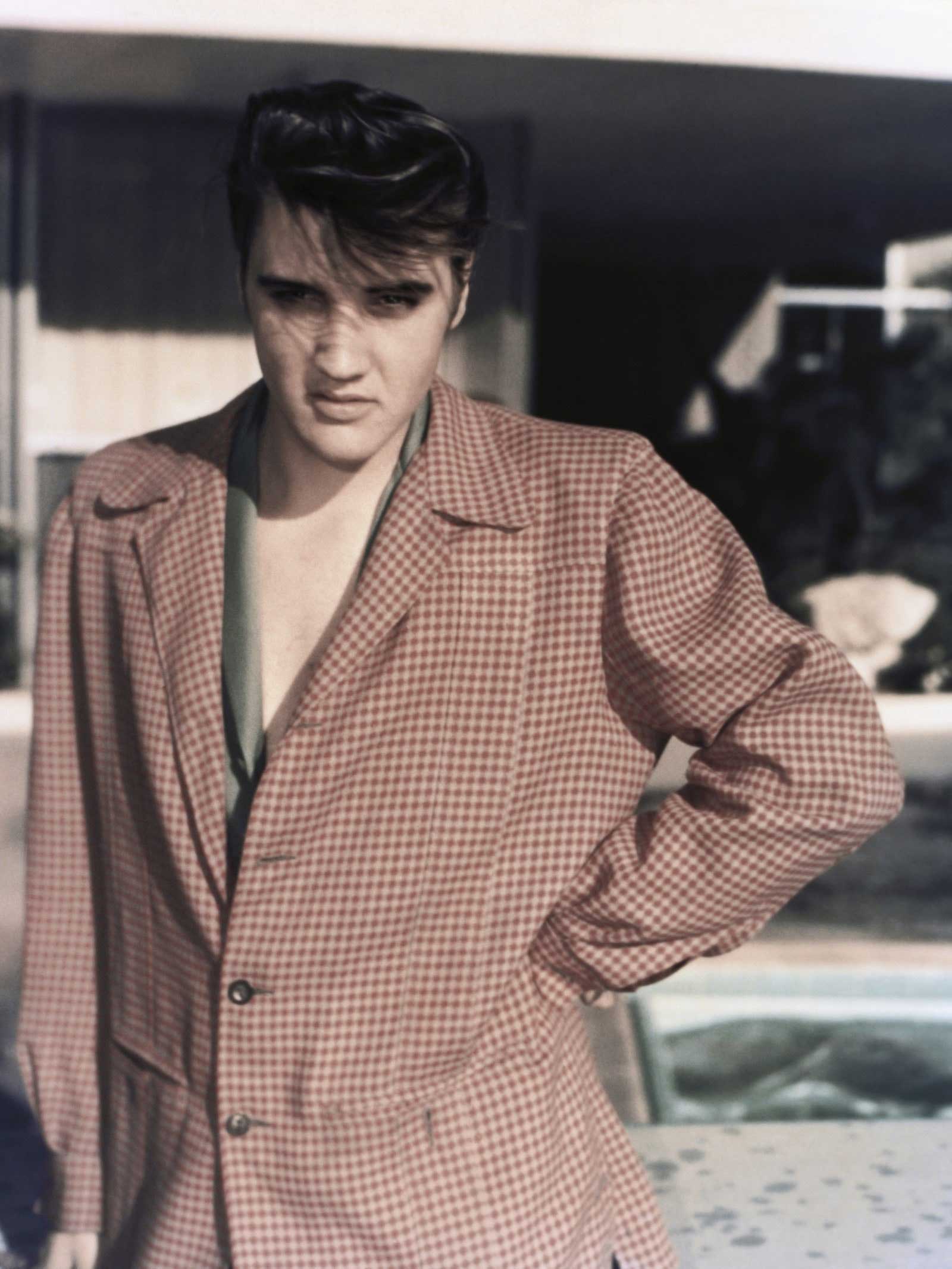

The men got their icons, too. The plain white tee donned by Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) sent fashion into a tizzy—the exposed T-shirt became a marker of a bad boy. Paired with jeans, as worn by James Dean (1955) in Rebel Without a Cause, the look represented a youthful flout of bygone formalities. As women’s fashion matured and required much maintenance, fashion prized a boyish ease for men.

Here Come the Stilettos

Slender shoes rise in popularity—and height

It’s unclear who exactly “invented” the stiletto and, for that matter, what makes a stiletto a stiletto. The word (Italian for dagger) was first documented as a description of a pointed, slender toe of a shoe but quickly came to describe a tall slender heel. What is certain is that there were three main proponents of the style: Roger Vivier, Salvatore Ferragamo, and André Perugia. It’s also certain that the heel’s rise in popularity started in the early 1950s. The slender, un-clunky shoe was the perfect punctuation for the decade’s graceful fashions.

At the time, Roger Vivier was designing footwear for Christian Dior. The Vivier name appears alongside Dior’s inside each shoe as Dior claimed out of all his collaborators, Vivier was the only other artist who could get equal billing on a label.

Lesser-known today is the footwear engineer André Perugia who, in the early 1950s, was gaining press for his steel-based heels. The November 15, 1951 issue of Vogue celebrated the novel rhinestone-encrusted, whisper-thin steel heel from Perugia.

“The new suspension sandal, above. Standing on a thin-strip of metal, the most spectacular shoe idea yet devised for evening. (Sideways, there appears to be no heel at all—only a thin strip of rhinestones.) Still a Perugia dream, this idea for a slight, thin—and unforgettable—sandal will be continued in the workrooms of I Miller in America.”

Then there’s the Italian Salvatore Ferragamo, who is credited for inserting a steel rod into the heel of a stiletto, which was commonly made of wood. Ferragamo’s relationship with Hollywood starlets like Marilyn Monroe helped propel his designs to prominence.

Top Designers of the 1950s

Christian Dior, Balenciaga, Mainbocher, Paquin, Pierre Balmain, Jacques Fath, Norman Norrell, Nettie Rosenstein, Vera Maxwell, Hubert de Givenchy, Emilio Pucci, Claire McCardell, Bonnie Cashin, Pauline Trigère, Hardy Amies, Norman Hartnell, Edward Molyneux, Digby Morton, Creed, Charles James, Pierre Cardin

Men’s Trends of the 1950s

If the postwar lady got her New Look from Dior, the post-war gentleman was treated by tailors on Savile Row to the New Edwardian look—a slim-cut suit, sometimes three pieces, and sometimes with a velvet collar. Jackets were single-breasted and accessories came by way of bowler hats and silver-capped canes.

In addition to the youthful, wrong side-of-the-tracks looks delivered by Marlon Brandon and James Dean on screen—think denim, tee, and sneakers—a whole new archetype emerged in the 1950s. The “Teddy Boys” or “Teds”-look dominated in youth subculture—especially in Great Britain. These Teddy Boys wore narrow suits and trousers and greased their hair back into quiffs. It was an aesthetic that resonated with musicians in the UK before Elvis took the look and blew it up stateside.

In the Culture

Where to begin! On-screen, the world met Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday. Hollywood exploded with bombshells Marilyn Monroe, Ava Gardener, Ertha Kitt, Jayne Mansfield, Elizabeth Taylor and more. In 1956, Hitchcock’s favorite blonde swapped Hollywood for Monte Carlo, marrying Prince Rainier of Monaco in a lace wedding dress designed by Helen Rose. And speaking of royalty, Queen Elizabeth II ascended the throne of the United Kingdom in 1953, wearing a dress by Norman Hartnell. Her reign coincided with the return of courtly balls after a period of austerity, and the events promoted British design,

In 1952, Jack Kerouac published On the Road, which was gobbled up by the beatniks who called Manhattan’s Greenwich Village their HQ. In music, Elvis Presley divided households with his scandalous gyrations on stage, earning him the nickname Elvis the Pelvis. Then you had Little Richard, Bing Crosby, Ray Charles, Frank Sinatra, and more to choose from.

In 1959, the world got its very first Barbie doll.

Vogue World: Paris will pair select sports—cycling, gymnastics, tennis, taekwondo, fencing, and break dancing, among others-with French fashion from every decade since 1924. The show will showcase French designers, current and past, as well as houses that historically present their collections in Paris.

For front row tickets, email [email protected]

This article was originally published on Vogue.com.