Tati Miranda-Fortuna’s banig-inspired bag fuses traditional Filipino weaving with sustainable design, championing the craft of Aroroy artisans.

“My inspiration for this banig bag is a town in Masbate called Aroroy,” Tati Miranda-Fortuna, founder and president of ucycle, shares. “Banig is something that Filipinos used to grow up with. It is a sleeping mat. And for those who are familiar, it invokes the feeling of home.”

Aroroy, a town nestled between a mountain scarred by mining and prone to occasional flooding, faces significant challenges. Extensive mining activities in the area have depleted the buri palm trees, which are essential for making banig, leading to a decline in traditional weaving. Despite this, the Manamoc Aroroy Masbate Community of Women Banig Weavers have harmoniously married traditional craftsmanship with contemporary design.

One of which is Nanay, who was taught by her mother and has been weaving for 50 years, says the craft makes a difference in their lives. “Naka bulig man kay kung maturotikapok makabaligya banig naka bakal na san kung nano ang wara namon,” [“It’s helpful because when we’re short of expenses, we can just sell a mat to buy what we don’t have.”], she says.

Nanay’s story goes way back:

“Kay san ano san inan ang akon iloy san nabalo sya ako ang puto. Ako ang pinaka manghod. Unom palang ako kabulan napatay na ang akon ama. Tapos ang gina himu sadton akon iloy naga himu sya sin banig, kalo, kag mga handbag amun gina himu niya. Amu ang gina kuan sa amon. Amo ang gina suporta sa amon kay upat la kami. Tapos pag ano pag san my buot na ako, nag sigen kita ko hasta nakaaram nako. San nakaaram na ako di my pamilya nako pag ada ako sa balay na inahon kuan wara akon iba na opisyohon amu idton akon gina himu naka bulig bulig na sa akon pamilya pag kun nano na wara namon kag natitikapo nakabuligbulig na gid idtu miskan nala pagbakal sin sura.”

[“I was only six months old when my father died. To provide for the needs of the four of us, my mother wove mats, hats, and handbags. Growing up, I watched her make banig until I learned the craft myself. Once I had my own family and was at home with time on my hands, I began making mats as well. This helped with daily expenses, such as buying food.”]

Despite running into logistical hurdles in sourcing and transporting materials, “back-and-forth of materials from Manila to Masbate to Aroroy … and back to Manila,” Tati expresses that the effort is well worth it for the weavers. “Seeing their joy and their faces, helping honor and celebrate their craft, and of course, giving them hope,” she says.

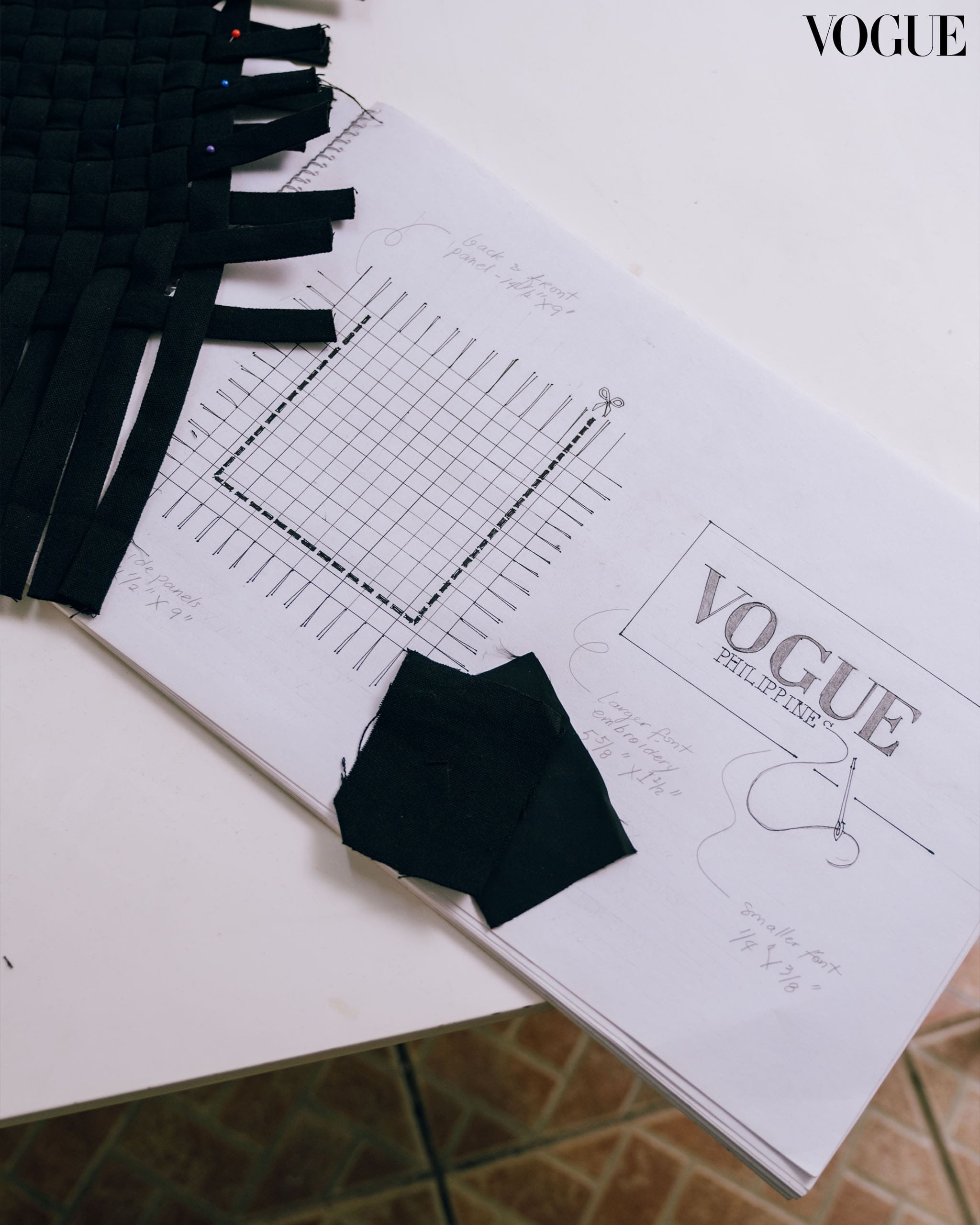

In response to the declining banig weaving industry, the design thoughtfully incorporates upcycled materials: the body of the bag is made from deadstock linen fabric, the interior is lined with recycled polyester, and the bottom base is constructed from repurposed billboard tarpaulins. “Billboard tarpaulins are made of plastic,” Tati points out. “If thrown in the landfill, [they] can take hundreds of years to decompose. In the Philippines, tarpaulins on billboards are everywhere, so I wanted to find a good way to extend [their] life. Design-wise, the tarpaulin gives the bag some structure and also strengthens the bottom base, which can make it sturdier and help prolong [its] life.”

Tati sees this collaboration with Vogue Philippines as a significant step beyond merely upcycling materials. It serves as a bridge between traditional Filipino crafts and contemporary audiences who might not fully grasp their depth and significance.

She adds that the Philippines is blessed with a rich and diverse culture, and that we “all have the responsibility to help promote and preserve [it]. No matter how small, what we can do to help, when done together, goes a very long way. My objective for this collaboration with the weavers is to shine a spotlight on their craft because it’s a dying [tradition], with the hope that there will be more interest and support.” Circularity, Tati says, extends beyond material reuse; it encompasses supporting the livelihoods of the weavers themselves. “It’s like breathing new life into a craft that’s dying,” she adds.

Tati envisions further engagement with communities and the preservation of traditional crafts through innovative approaches. “We are always trying to find ways to connect with communities with crafts that are slowly dying,” she says. “By incorporating these designs into something modern, we honor and preserve an important part of our culture.”

Photography by Trisha Enriquez, Kim Santos, and Andre Cesar. Managing Editor: Jacs Sampayan. Art Direction by Wainah Joson. Make-up by Nadynne Marie Esguerra. Hair by Patrick Domingo. Produced by Trisha Enriquez. Project Implemented by Michaela Acilo. Written by Chynna Tumalad Additional text by Tati Fortuna. Production Assistant: Bianca Ferro. Shot on Location at Aroroy, Masbate and ucycle Studio.