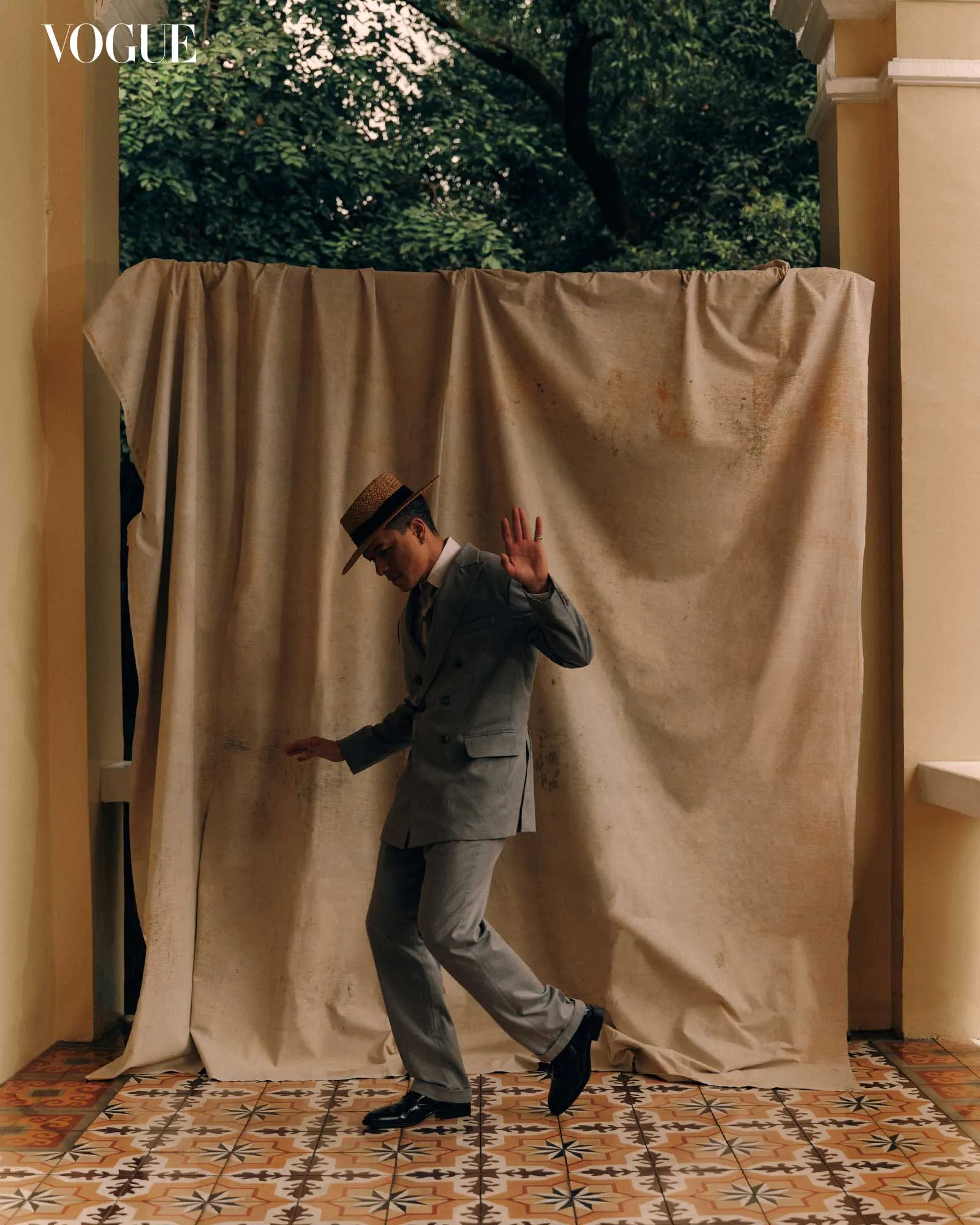

Photographed by Artu Nepomuceno for the October 2025 Issue of Vogue Philippines

To bring Manuel L. Quezon to the silver screen is to take on more than a role; it is to step into a nation’s collective memory and embody its history.

By the time Manuel L. Quezon was sworn into office in 1935, he faced the monumental task of leading a nation still defining itself. Just decades earlier, the Philippines had emerged from centuries of Spanish rule, only to be handed over to the United States after the Treaty of Paris in 1898; a shift from one colonial power to another. As president, Quezon would again confront a defining crisis, the looming threat of a second world war.

In an essay titled “The Quezon Papers,” historian Ambeth R. Ocampo notes that “our form of government was made in his image and likeness,” shaped by a man who steered a young nation through its growing pains. “What our government is today, both good and bad, has its roots in Quezon,” he adds.

Yet beyond politics, he was remembered for qualities that made him seem larger than life. Sepia portraits and black-and-white reels, preserved in the Quezon Memorial Shrine and Museum and the Quezon Heritage House, show him with slicked-back hair, sharply cut suits, and a presence that radiated charisma and conviction. Which begs the question: how does one bring such a figure, so firmly embedded in the nation’s memory, onto the silver screen?

Because of this, the making of Quezon as a film emerged with even more questions. Who could convincingly embody the late president? How did he carry himself among colleagues, at home with his family, or in public? What did he wear, and what did those choices say about the man?

As the film’s lead, Jericho Rosales felt that these answers were not easy to come by. Although he agreed to the role, responding to director Jerrold Tarog’s call with no hesitation (something he almost never does without reading the script), the veteran actor’s doubts still continued to linger even after production. “I’ll be honest with you, it’s like ‘Can I do this?’” he recalls. “I don’t look like him. How does he talk? Who among my friends were close to people that knew him? Where do I even start?”

And for nearly half a year, the team attempted to answer these questions as they moved between fittings, hours spent in plaster molds, makeup tests, and months of filming; all to capture the late president’s likeness. The uncertainty eased, if only briefly, during his shoot with Vogue Philippines. Enrique “Ricky” Quezon Avanceña, Manuel Quezon’s grandson, happened to drop by the Quezon Heritage House between takes, just days after the holiday honoring his grandfather’s birth. Catching sight of Jericho in their ancestral home, he said, “You look like him.” Jericho remembers looking back and noticing the resemblance the other way around, “No, you look like him,” he replied. The exchange was quiet, but it carried a reassurance; the role could be lived into.

For Rosales, that meant translating his portrayal through finding the small gestures that might have defined the character beyond politics. “There’s what’s been written, right? So I’m not the one creating, just recreating,” he explains. “It was me hunting down or looking for people who knew him, family, friends, children, grandchildren, historians, and I had to ask them questions.”

But that translation was not Jericho’s alone. Alongside him, designer Joey Samson crafted a wardrobe that allowed the actor to step into the role. “I found out that he was so involved in the design of his barong and his suits,” says Rosales. Historical photographs show the details; carrying swagger sticks, fitted hats, sharply tailored suits with peak lapels, often accompanied by matching ties and pocket squares. “So I said I want my suits to come from art, from artisans, so that’s why I asked Joey.”

It was the first time the fashion designer had worked on costumes for a film. Still, much like the movie’s lead actor, he accepted the task almost immediately. His process began with poring over photographs, museum archives, and the few surviving clips of Quezon online. “It’s hard enough to make clothes as it is, but it’s even more challenging to create historical costumes with very specific references,” he explains. The difficulties extended to fabric sourcing, since most textiles from that period no longer exist. Suits then had a particular weight and drape; even shades of beige or black differed from today, determined by the density and finish of the cloth.

Despite this, the project felt both daunting and familiar. Known for his precision with the terno, tailoring, and classic dress patterns, Joey has long drawn from history in his practice. With limited references, he studied silhouettes from the 1920s through the 1940s, since the film spans several decades.

“The only way to be precise with each era is through the way of silhouette,” he says of his methodology. Alongside the looks of Aurora Quezon, created by designers Rommel Padillo Serrano and Jor-el Espina, Samson leaned toward historical accuracy as he developed a tuxedo and three suits to go alongside Quezon’s key scenes. “Since we couldn’t fully replicate the fabrics of that time, proportion and silhouette became my main selling points,” he adds. A turning point came during a makeup test at the National Museum, when he fitted Jericho into his initial wardrobe, and after seeing the scale of effort poured into the production, he thought to himself, “I have to get this right.”

It was a sentiment mirrored by Rosales in his own process of embodying Quezon. Both actor and designer found themselves shaped by the film in ways they hadn’t expected, deepening not just their understanding of history, but also their sense of what it means to be Filipino. For Joey, the work sharpened his attention to detail and his study of the past. As for Jericho, it became a question he carried with him in every scene: what defines a bayani (hero)?

If history often renders its figures untouchable, Quezon attempts the opposite. “Working on the film contributed a lot to the question of how Filipino I am,” Jericho reflects, and what began as a production inquiry quickly opened into something larger for the cast and crew: “How much do I understand about being Filipino? What should I hold on to, and what can I let go of?” he adds. These questions followed them beyond the set, into press tours and school visits, inviting a series of discussions that probed the thin line between bayani and leader. In revisiting the man, the film asks its audience to do the same, to confront what it means to belong to a nationality, and to imagine, as the former president once did, the nation we might still become.

See more exclusive photographs from this story in the October 2025 Issue of Vogue Philippines, available at the link below.

By GABRIEL YAP. Photographs by ARTU NEPOMUCENO. Fashion Editor DAVID MILAN. Vogue Man Editor DANYL GENECIRAN. Talent: Jericho Rosales. Designer: Joey Samson. Talent’s Team: Pinky Angodung, Karen De La Fuente, and JL Yanga. TBA: Nini Oñate and M de Mesa. The Quezon Heritage House: Krystal Belino. Producer: Julian Rodriguez. Media Channels Producer: Angelo Tantuico. Hair and Makeup: EJ Caro. Photography Assistants: Choi Narciso and Odan Juan. Shot on location at The Quezon Heritage House.