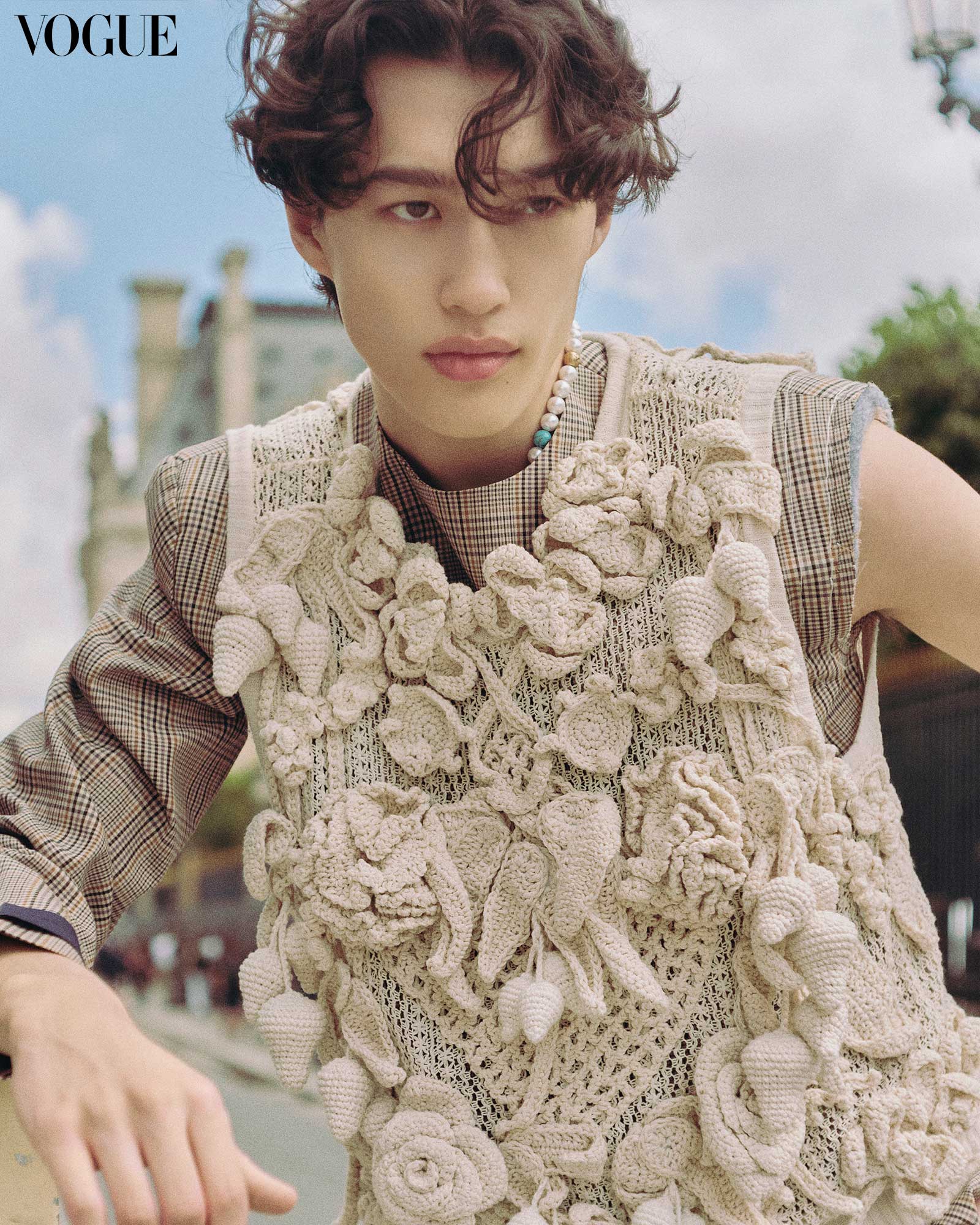

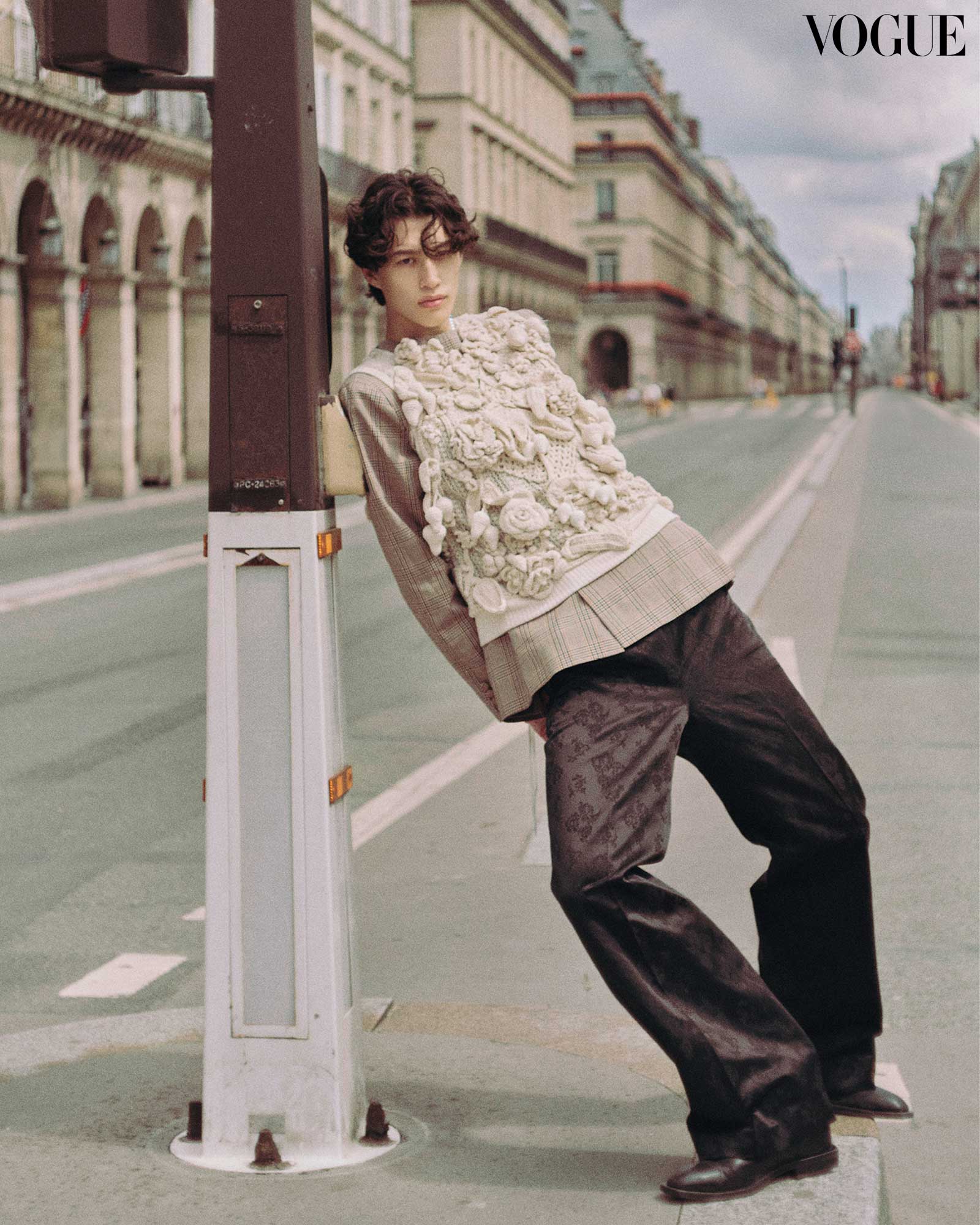

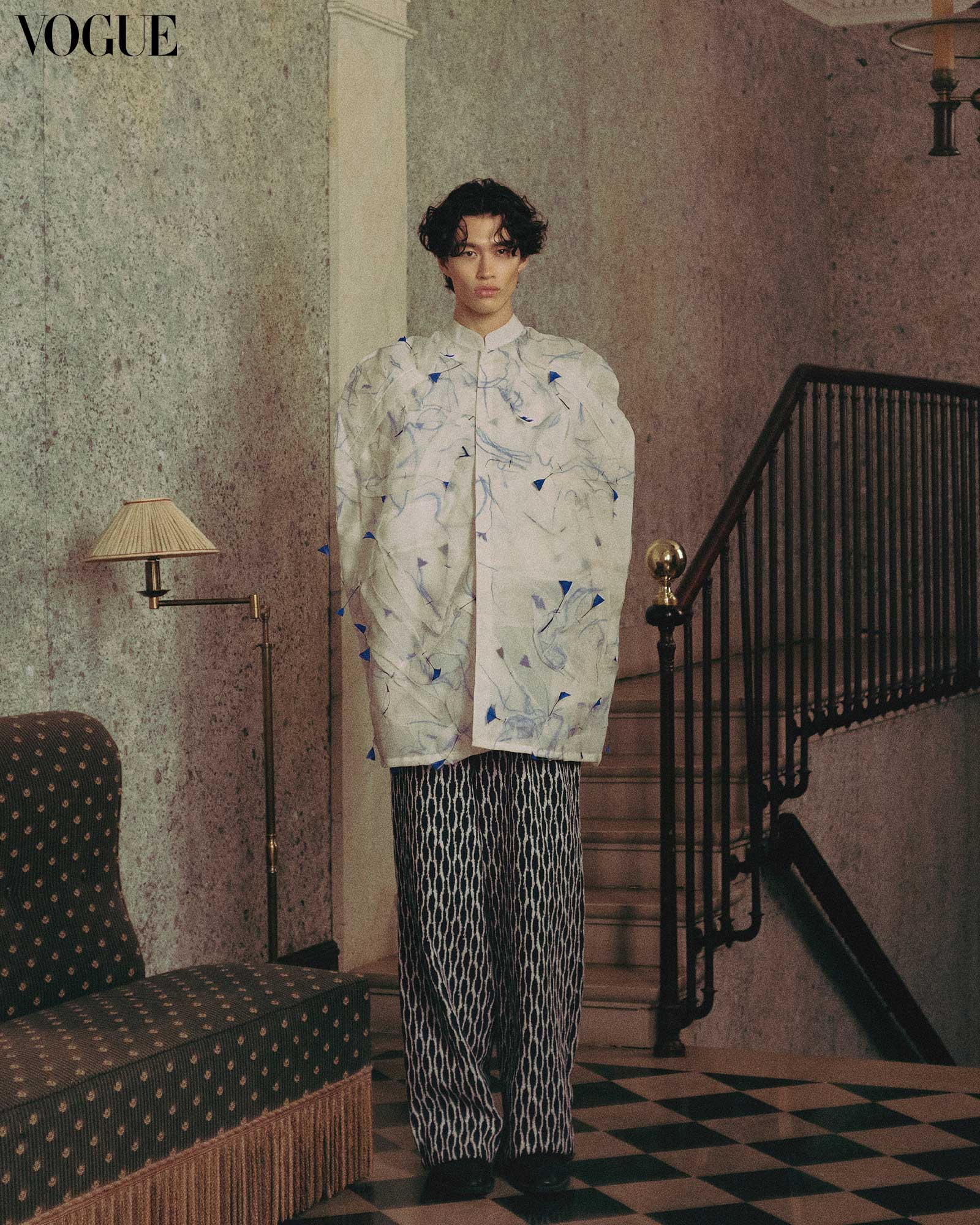

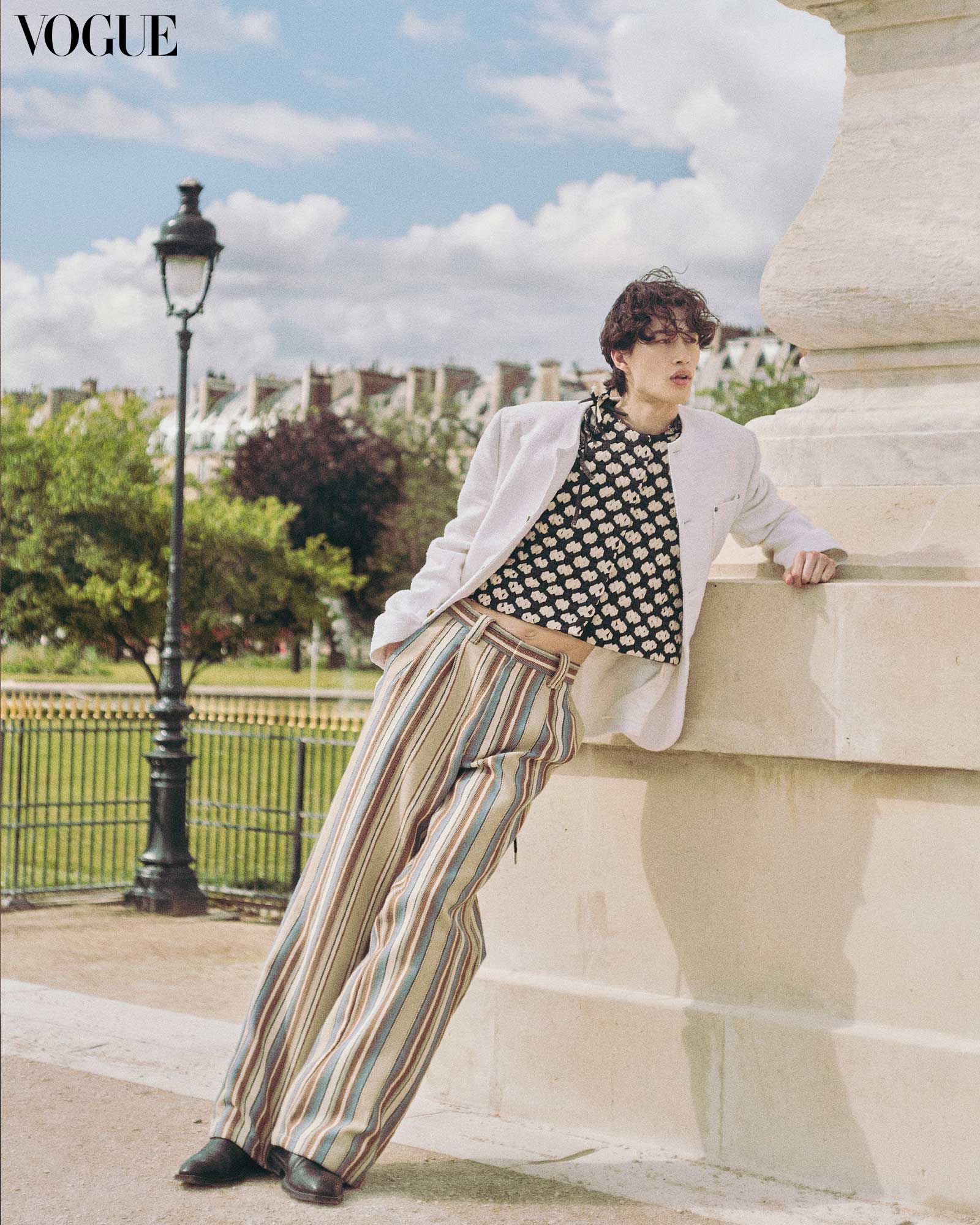

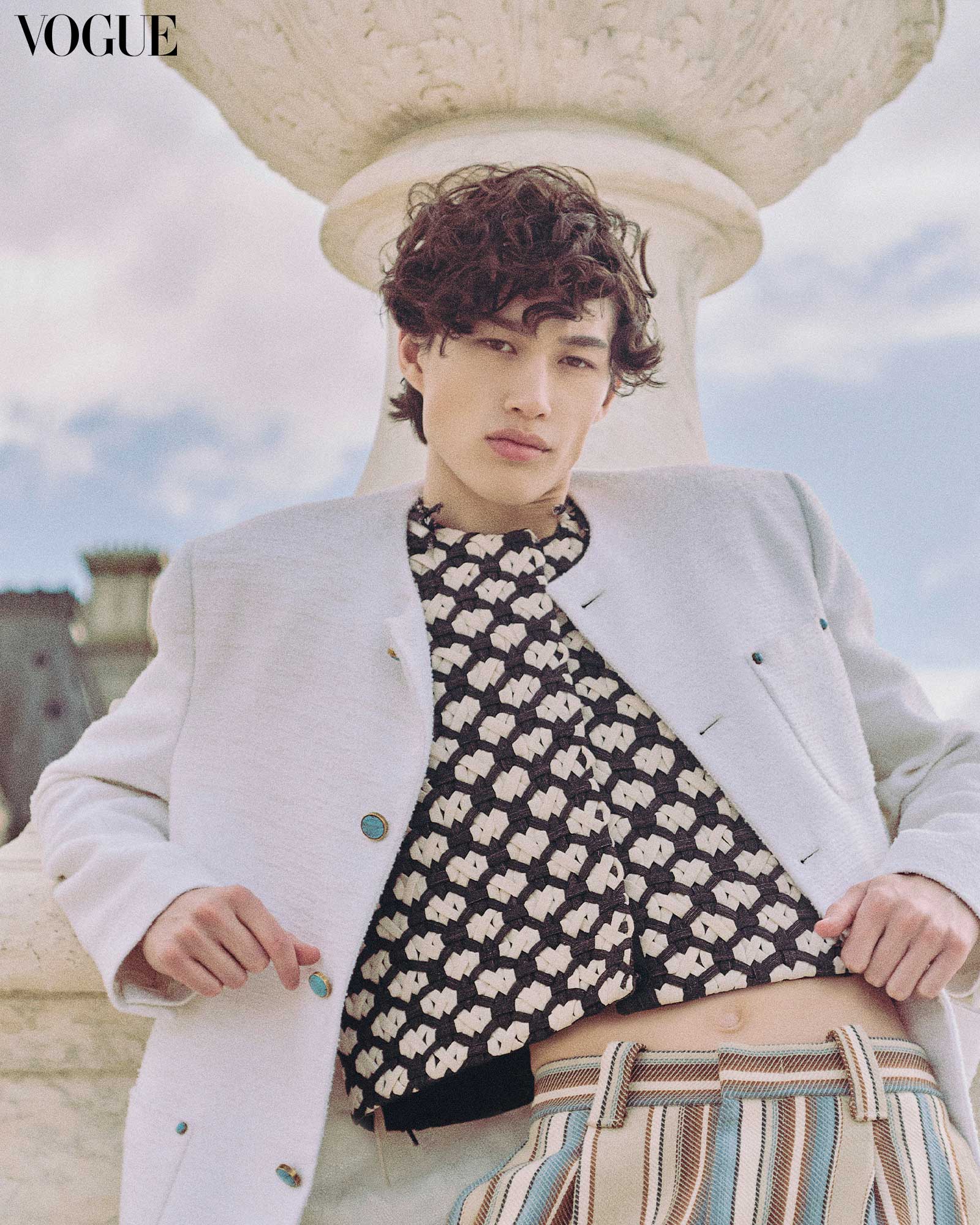

In times of economic or environmental bleakness, fashion remains a powerful source of emotional uplift. Top model Mathieu Simoneau showcases the creations of Filipino designers who emphasize meaningful investments and prioritize quality over quantity.

There are three kinds of neighbors you meet in Paris: the Good, the Bad, and the Ideal. Good neighbors are your run-of-the-mill, gluten-free eating, tote-bag bearing, generally discreet ones. They say hello in the corridors, always clean up after their dogs, and never start a washing machine cycle past a certain hour in the evening. Bad neighbors, on the other hand, decide to heavily vacuum their floors and rearrange furniture only after 10 PM. This is, of course, when they are not too busy throwing a techno rager in the middle of the week.

Once in a while though, you bump into the Ideal neighbor. They know all the good restaurants, they are kind without being intrusive, and will help you bring up a vintage dresser up four flights of stairs. Their style is distinctly Parisian—classics done to perfection, yet casual and effortless. On slow Sunday mornings, the sound of them playing Satie seeps through the walls. You suspect a small crush developing until you see them one day in the elevator, balancing a coffee cup over a gigantic ziplocked bag from an ultra-fast fashion chain.

You smile and say bonjour. Only two days ago, you’ve seen them frowning in concentration in front of the recycling bins, careful to put everything in the correct container. How could it be the same person ordering three euro tank tops from the other side of the world?

Talking about sustainability in 2024 feels the same: complex, extremely nuanced, and, most of the time, disillusioning. It has been a decade of discourse, numerous boycotts, industry-wide brainstorming and disruptive solutions. It seems that the conversation has plateaued and we are suspended in a limbo, between blatant greenwashing and uninspired missives. While strides have been made, in that same amount of time, the fashion cycle has accelerated even further, moving from fast to virtually instant.

Fast fashion has opened up the world of personal styling and runway trends to a much larger demographic. It has allowed many individuals to express themselves through clothes without drafting out big coins. With prices for everything at an all-time high, this seems vital. It’s very easy to antagonize people who buy fast fashion until you hear a younger cousin with a shy monthly allowance moon over a potential prom dress seen at the mall or people trying to make ends meet desire to inject a little joy into their lives. You consider that perhaps, the situation, like most post-modern enigmas, is not fully black and white.

“The most sustainable way of owning clothes is to only produce it when there’s demand, and to produce it in a more personal way.”

Jude MacasinagAdvertisement

These negotiations, however, occur at a time when the looming climate crisis is hitting us harder than ever, with each strike more erratic and treacherous than the one before. In July of this year, images of a heavily flooded Manila and Central Luzon following the landfall of typhoon Carina were broadcast all over the internet. While scenarios like this have unfortunately become a recurring episode in our collective memory—misery outsourced somewhere else, happening off-screen—they highlight a developing narrative: the unequal impact of climate change. The Philippines has a minimal carbon footprint, yet we find ourselves increasingly caught in the eye of the storm.

In times of external distress, there is a tendency to look within, to focus on things within our control. What can we do on an individual level? You perfect your morning routine, make small changes, and ensure every purchase is intentional. Yet, we find ourselves taken in by the waves. We surf on news cycles, swinging from urgency to indifference. There is an overall feeling of bleakness with the general state of global affairs. As we swipe through our phones, we are saturated with the same images. Nothing feels fresh or new. Will collective fatigue eventually lead to newer perspectives and renewed call to action?

Fashion, beyond the industry level, has often been relegated to the trivial. Yet, it has proven its cachet, time and again. Amidst the quagmire of geopolitical concerns on top of our personal urgencies, we appreciate brief changes in static. The soft touch of a dry silk shirt from Lemaire remains nothing short of magical when tried on. How shiny, new penny loafers can put a spring in our step, or how a Thom Browne tailored wool trousers make us stand a little bit straighter. Fashion as a vehicle for dreams, a catalyst for emotion. Desire. Surely, in a time of collective despair, a reliable source of pleasure, albeit fleeting, must have a certain value worth considering.

However, what separates the noble pursuit of staying inspired through material aspirations and falling into another consumerist pitfall is a very fine line. A report by Euromonitor International states that daily doses of happiness can invigorate and uplift emotions. “Consumers want to take their minds off everyday stressors and a chance to break away from the mundane.”

The trend of dopamine dressing illustrates how clothes can have a positive effect with regards to our morale and self-image. It teaches us that we can hijack our brains and our bodies into happier, more optimistic versions of ourselves. While a perfectly cut suit or the right shade of red could potentially tide us over with our sanity intact, is there a way to do it and stay within the parameters of sustainable consumption?

Looking for answers closer to home, local designer Jaggy Glarino insists on heritage. Working with deadstock fabrics and incorporating traditional craft, he champions the Filipino soul when it comes to design. A certain inventiveness and an unforgiving hand on details and finishing. “The concept of heirloom fashion pieces is really appealing to me, as it represents a significant shift away from fast fashion,” he shares.

Another point to consider is the strong culture of bespoke creation, a service that is available across a variety of price points. “I believe our tailoring works under sustainable practices,” notes designer Vin Orias. “From precise measurements, efficient cutting, hand stitching techniques, the slow yet efficient process of crafting clothes makes us competitive in the market.”

Beautifully designed clothes, cut and tailored to fit one’s proportion—so the antidote to fast-fashion is, surprise, couture? Not necessarily. The pagawa culture is ingrained in socio-economic structures and it is a service that is available across different price ranges. Infused with emotion, this sense of participating in the design process transforms a garment into a personal piece—one that is cherished and harder to dispose of or forget at the back of the closet.

“The most sustainable way of owning clothes is to only produce it when there’s demand, and to produce it in a more personal way,” highlights Paris-based Filipino designer Jude Macasinag. “It’s the wearer’s relationship with the garment that makes it last longer, idealistically diminishing the excess of unwanted clothing around us.”

Well-placed emotions, sentimental investment into each object we bring back home, taking stock of our personal consumption and putting a prime on quality over quantity. All of these we already know, on our certain level. When I saw my neighbor, I wished I asked them for more insight, to genuinely exchange out of curiosity. In a time of information overload, maybe we should not be nose-deep looking for answers but instead focusing on asking the right questions. To probe, relentlessly, but always with the respect and graciousness you would extend to a shy cousin or a favorite neighbor.