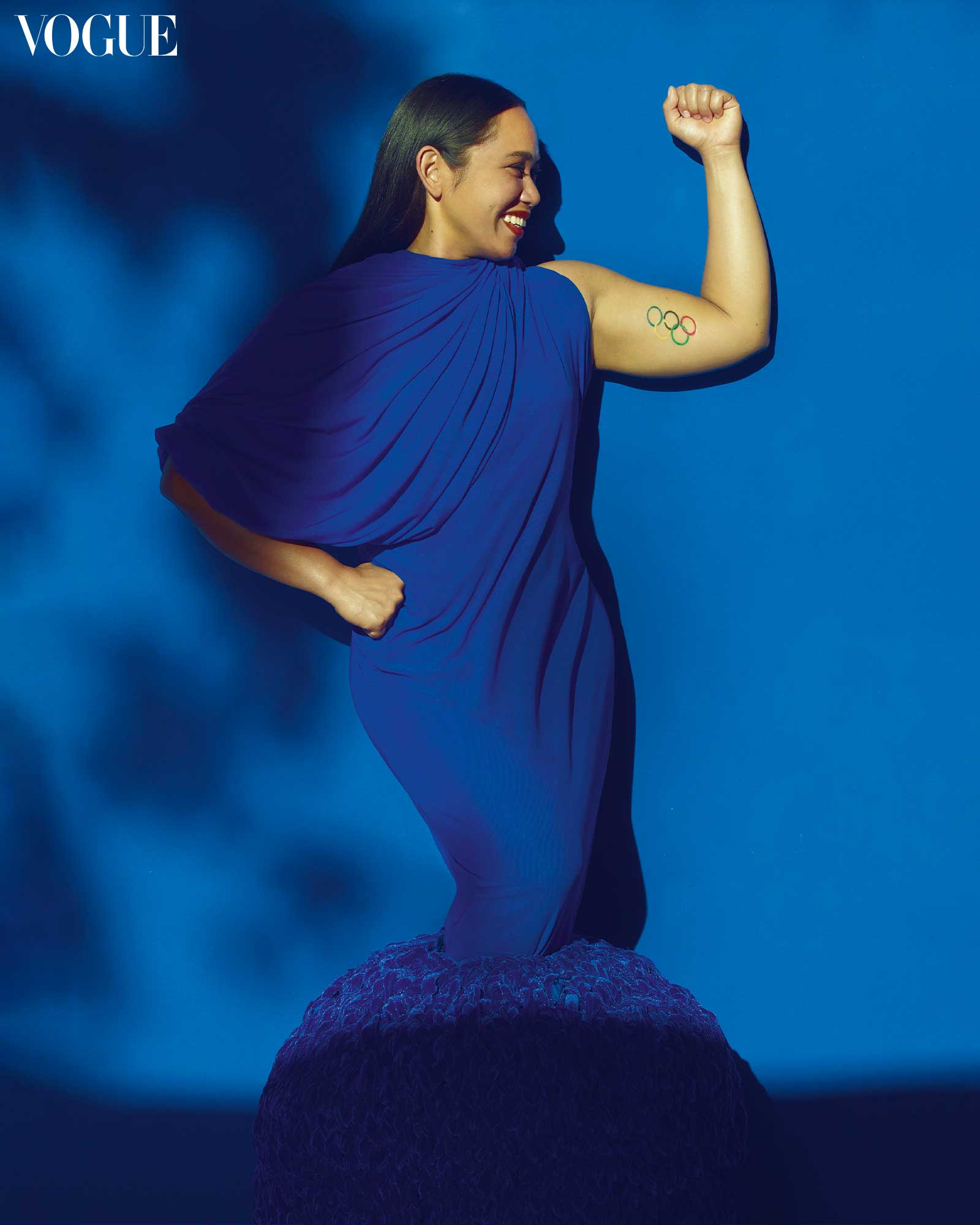

Olympic gold medalist Hidilyn Diaz is thinking of starting her own family and, unsurprisingly, working hard to earn the privilege of representing the country again.

The sound of the buzzer was deafening as the words “No Lift” came on screen. It’s a sound Hidilyn Diaz has heard many times before and while it was normally followed by deafening cheers, it was different this time. With much dignity, Diaz smiled and gave a small wave and a bow to the crowd as she left the platform. It was that moment that signaled the end and, somehow, the beginning of something new.

“I could give a lot of excuses, but Paris just wasn’t for me,” Hidilyn says with a smile that was both sure and serene. The weightlifter, who won Gold in the 55-kilogram weight class in Tokyo in 2020, missed her chance to qualify for her fifth consecutive Olympics at the 2024 International Weightlifting Federation (IWF) World Cup held in Phuket, Thailand, this April. Diaz, who has competed in every Olympic event since 2008, left many disappointed when they learned she won’t be participating in this year’s Summer Games.

“I haven’t seen the video of my performance in Phuket,” Diaz admits. “But I remember that at that time, the only thing on my mind is that it’s done. Olympic qualifiers are long and arduous. You have to be in the top 10 for several competitions.” As she exited the platform, she knew that her journey to compete in Paris had come to a screeching halt. She gave the crowd a smile, a wave, and a dignified bow. “I’m still happy because I did not give up. I showed up and I did my best.”

Recovering from an injury at the 2023 IWF Grand Prix in Doha and moving up to the 59-kilogram weight class after the Olympics scrapped the 55-kilogram event are two key factors experts cited for Diaz’s struggles in Phuket. For the weightlifter, however, these setbacks are already behind her. “Instead of focusing on what went wrong, I choose to move on from it.”

She also feels better because a Filipino, Elreen Ando, qualified for Paris. “She deserved it. She trained hard,” Diaz says. “I’m happy for every Filipino athlete who qualified. We’re increasing in number so that means Filipino athletes are getting stronger. Not just in weightlifting.”

While some might interpret this as the end of an era, it’s merely the start of a new chapter for our first Olympic champion. “I’m not done with weightlifting,” she emphasizes. “But right now, my priorities are shifting slightly.”

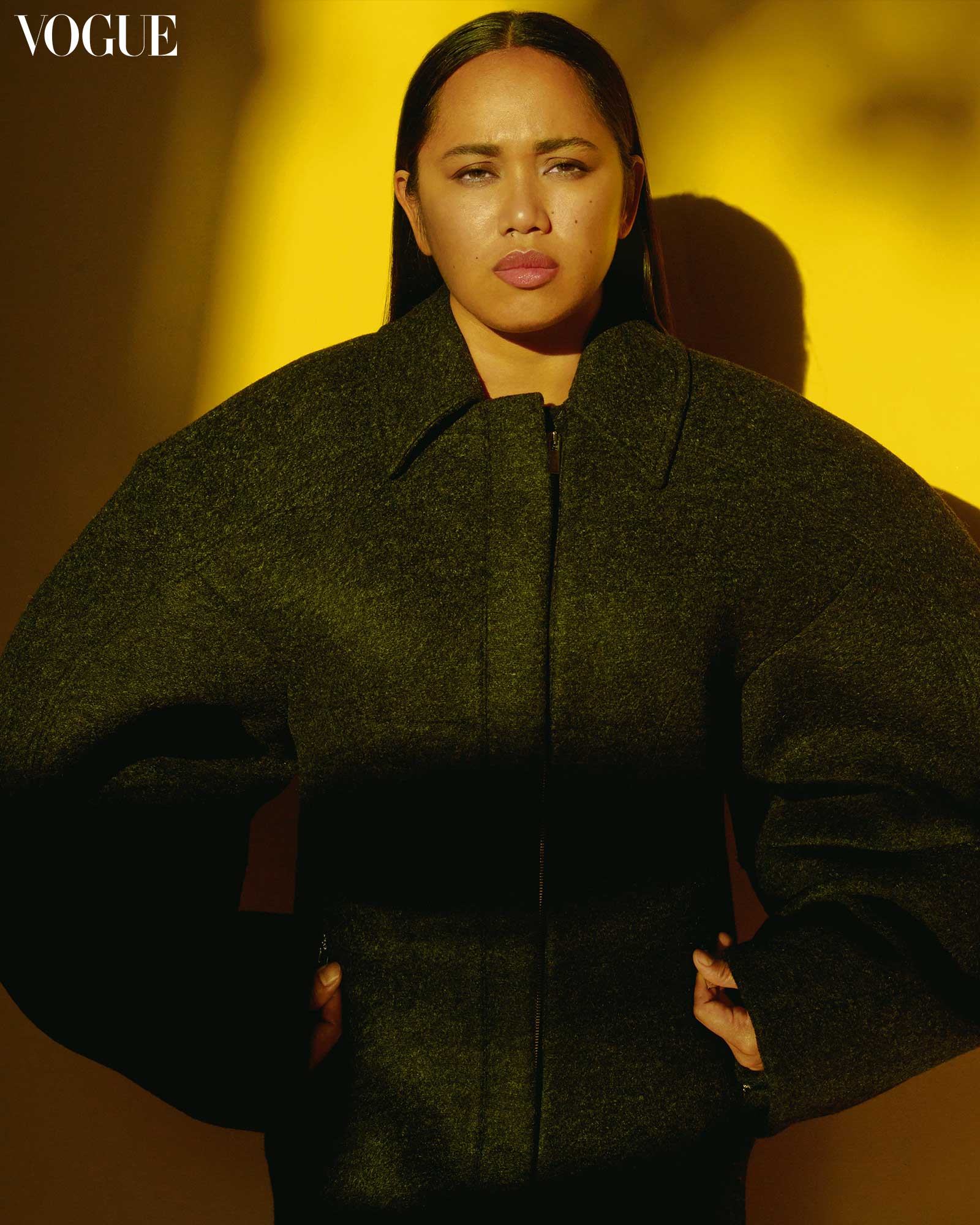

After Diaz and her boyfriend-turned-coach, Julius Naranjo, got married in 2022, Diaz has repeatedly mentioned that time together outside of weightlifting has been scarce. Aside from training for competitions, the couple have also opened the Hidilyn Diaz Weightlifting Academy. Located in Jala-Jala, a municipality in the province of Rizal that’s about a two-hour drive from Metro Manila, the academy is where Diaz spends most of her days. “I really like it here,” she says. “I enjoy being in the province. It’s a lot more quiet and I can focus better.” At the academy, she trains for her competitions and helps Naranjo train the next generation of weightlifters.

“Most of the family has gone into weightlifting. About eight of my nieces and nephews are now into the sport,” Diaz says proudly. The academy stands as a testament to her enduring commitment to the sport and her desire to nurture future talent. “In Zamboanga, weightlifting is quite popular as we’ve been winning medals since the ’80s. But a female weightlifter? It wasn’t a thing. In my first weightlifting event, I had no competitor. Now, it’s different. There are more female weightlifters than men.”

“I’m not sure what’s next… if I’ll even try for the next Olympics. But what I know is I want to be a mom first”

Advertisement

After the Rio Olympics, Diaz had a gym built in Zamboanga where her cousin coaches aspiring weightlifters. Now, with the academy in Jala-Jala, these two places are now homes to future Philippine representatives. Diaz’s time is divided between balancing her own training with coaching responsibilities. “I always do my best when I’m training so once the competition comes, things start to feel automatic,” she explains. This methodical approach to training has been a cornerstone of her success and a lesson she eagerly passes on to her students.

“There have been times when I wanted to give up but it really goes back to my ‘whys’ which is why I’m still here. I love weightlifting. Weightlifting has been part of my life for 22 years,” she says. “Knowing your ‘why’ is important in being an athlete. It’s what makes you stay and keeps you going when the road gets tough.”

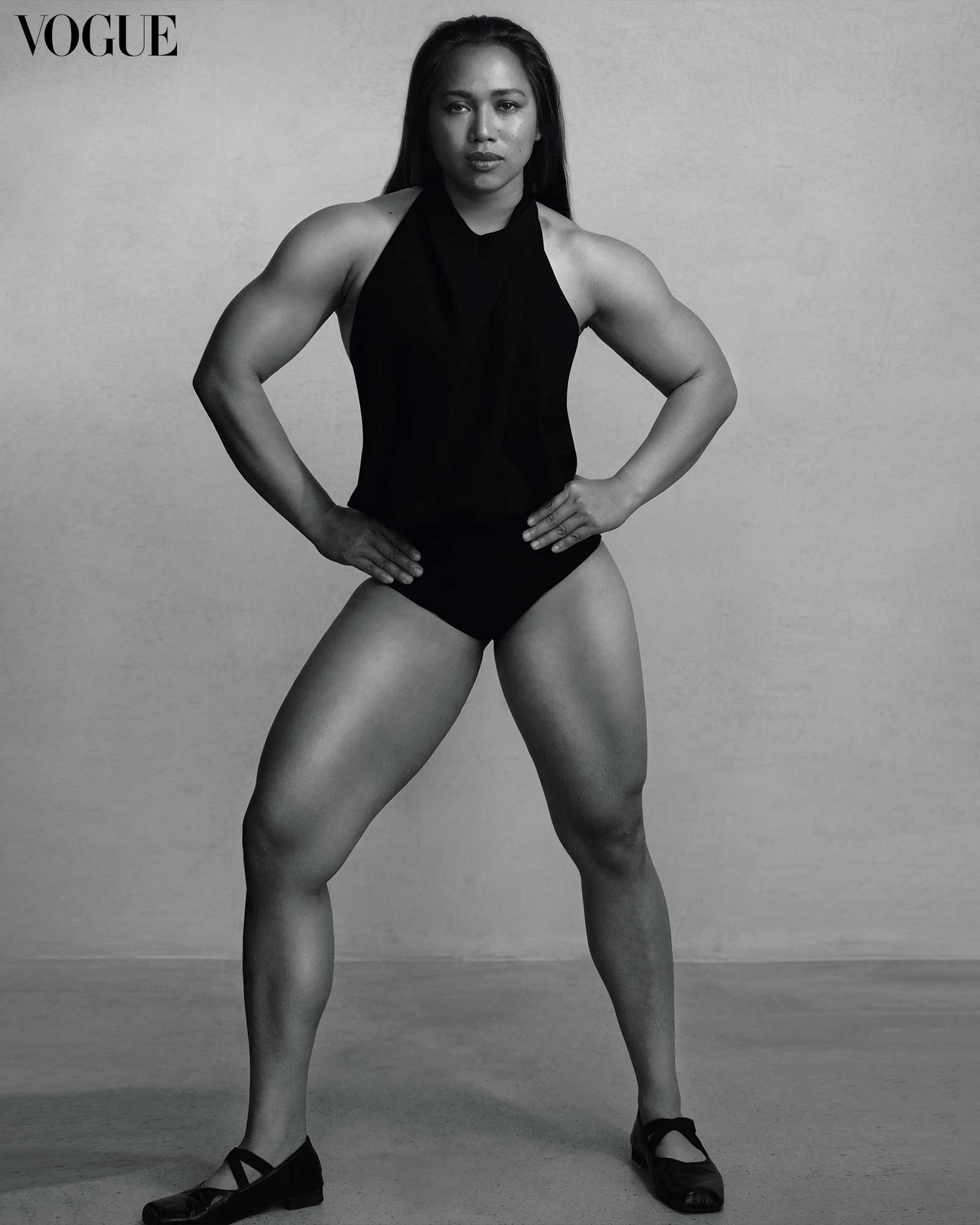

According to Diaz, true athletes know that being in sports is not just about medals and records. “After I won in Rio, I realized the responsibility it comes with. It’s not just about medals. After Rio, I saw the impact of what I’ve done. The kind of happiness and hope I was able to give to other athletes. I took on that responsibility because of the youth. At that time, kids were looking at me and thinking that hey, a medal is possible. The responsibility became heavier after winning the gold in Tokyo, especially because of the timing.”

Diaz’s historic win came at a crucial time. It occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic when the Philippines had some of the strictest lockdown measures. Adding to the significance of her victory was the fact that she defeated China’s Liao Qiuyun. For many Filipinos, it was more than just a sports triumph; it symbolized standing up to China, which has been asserting claims over Philippine waters and harassing Filipino fishermen. Diaz’s win was seen as a powerful statement that even underdogs can achieve great victories.

“It was about showing the world what Filipinos are capable of, even under the hardest conditions,” she reflects.

As Diaz transitions into a new phase of her life, she and Naranjo are focused on building their family. “We’ve been trying for a baby for two months now, but we’re not pregnant yet. We thought that just because we decided to try and stop using protection, it will happen right away. But it hasn’t yet. Turns out there’s prayers involved,” she said with a laugh. “But we’re ready. We’ve been asking our friends how life is with kids. Sleep schedules, feeding, and everything we need to know.”

The couple’s dedication to their future family life is palpable. Diaz is learning how to cook, bake, and drive—all skills she believes will be vital as they navigate parenthood. “I’m not sure how pregnancy will affect my weightlifting career. Studies say it’s okay to keep going and some weightlifters only stop in the third trimester. I might go crazy if I fully stop,” she admits. “But my main concern is what happens when the child is there. Everyone says I won’t be sleeping for years so now I’m asking myself how I can do it but I know that once we have a baby, we’ll figure it out.”

Despite her shifting focus, Diaz’s passion for weightlifting remains undiminished. She takes great pride in her role as a mentor: “As a coach, you have so much influence on an athlete. You’re able to instill discipline and share your perspective. Seeing them lift a certain weight they thought they couldn’t really makes me proud. We also teach them life skills and critical thinking. We try to empower them. I feel happy I get to help shape them into upstanding athletes and citizens. I guess that can be a form of mothering, but it’s still different to have one of our own.”

While Diaz remains undecided about her future Olympic participation, what she knows is her weightlifting journey is far from over. When asked if quitting while she’s still ahead ever crossed her mind, Diaz is adamant in saying no. “We’re athletes. We’re not just here for records. We actually have lots of failures in earlier competitions and during training. But the heart of the athlete is about never giving up. Weightlifting is part of my life and winning gold will not make me stop.”

She says that “there’s pressure after winning the gold. People expect me to perform at my highest level all the time. But athletes know it cannot always be the case. I love pressure. After the Paris qualifiers, I said I don’t want any pressure. But now I’m looking for it again. I need it to be challenging.”

Despite not qualifying, we will still see Diaz at the games as an athlete’s representative and a member of the IWF Board. “Sometimes, I still get sad that I won’t be competing in Paris this year. It’s my goal to be there. Thankfully, I’ll still be present but in a different capacity,” she says. Instead of passing the torch, Diaz will be sharing its light with athletes from all over the world. “I’ll be there to say hi to the athletes and cheer them on. I’ll be happy if another Filipino brings home a medal during these games.”

When will we see her on the platform again? Even Diaz doesn’t know. “I’m not sure what’s next. If I’ll even try for the next Olympics. But what I know is I want to be a mom first.”

While focused on giving back and dreaming of their future family, Diaz only hopes that she and Naranjo will have children who would grow up to be good people. “I want my own kids to grow up as good people, good Filipinos. I want them to be happy, independent, and to finish their studies. I hope they’ll have skills to be able to give back to the country.” Would she want them to take up weightlifting? She says it will only be up to them. “If they want to, I won’t stop them. I won’t force them into it because they have to really want it. That’s something I also tell our kids at the academy.”

As the interview draws to a close, we ask Hidilyn Diaz, “Where are you off to now?”

She smiles, her eyes reflecting a deep sense of purpose. “To the academy,” she replies with resolve. “The kids are waiting.”

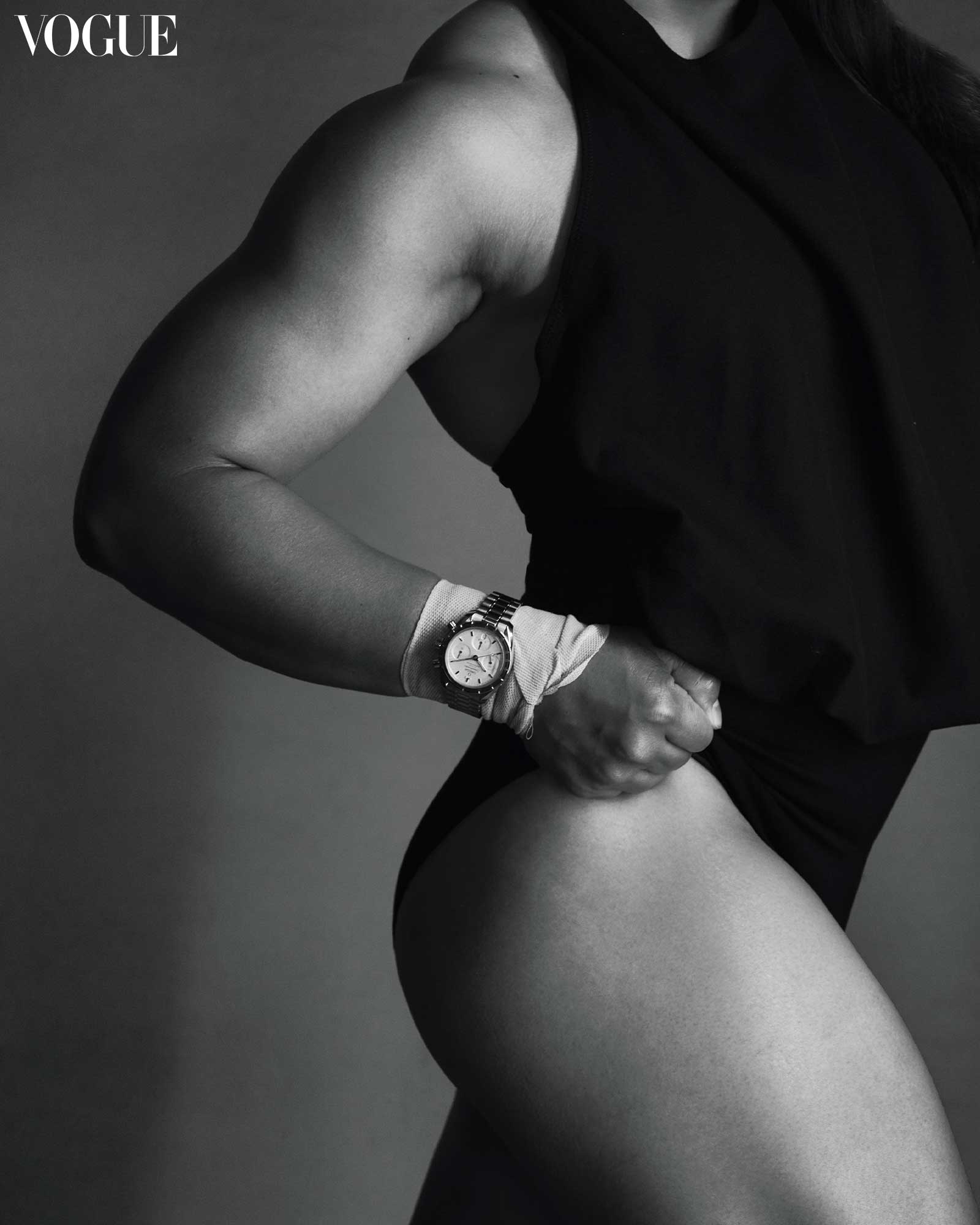

By CAROL RH MALASIG. Photographs by MARK NICDAO. Fashion Director: PAM QUIÑONES. Art Director: Jann Pascua. Makeup: Juan Sarte. Hair: Celeste Tuviera. Production Design: Justine Arcega-Bumanlag. Producer: Anz Hizon. Nails: Extraordinail. Production Assistant: Bianca Zaragoza. Multimedia Artist: Tinkerbell Poblete. Photographer’s Assistants: Arsan Sulser Hofileña, Crisaldo Soco, John Phillip Nicdao, Villie James Bautista. Stylist’s Assistants: Jia Torrato, Jill Santos, Neil de Guzman. Shot on Location at Balay Kobo